Mexican wolf

| Mexican wolf Spanish: Lobo mexicano Nahuatl: Cuetlāchcoyōtl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captive Mexican wolf at Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus |

| Subspecies: | C. l. baileyi |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus baileyi (Nelson & Goldman, 1929) | |

| |

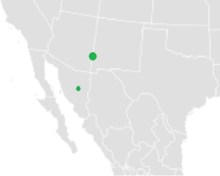

| C. l. baileyi range | |

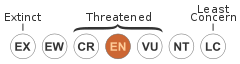

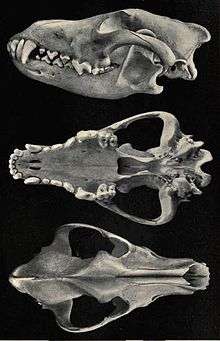

The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), also known as the lobo, is a subspecies of gray wolf once native to southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas and northern Mexico. It is the smallest of North America's gray wolves,[2] and is similar to C. l. nubilus, though it is distinguished by its smaller, narrower skull and its darker pelt, which is yellowish-gray and heavily clouded with black over the back and tail.[3] Its ancestors were likely the first gray wolves to enter North America after the extinction of the Beringian wolf, as indicated by its southern range and basal physical and genetic characteristics.[4]

Though once held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico,[5] it is the most endangered gray wolf in North America, having been extirpated in the wild during the mid-1900s through a combination of hunting, trapping, poisoning and digging pups from dens. After being listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1976, the United States and Mexico collaborated to capture all lobos remaining in the wild. This extreme measure prevented the lobos' extinction. Five wild Mexican wolves (four males and one pregnant female) were captured alive in Mexico from 1977 to 1980 and used to start a captive breeding program. From this program, captive-bred Mexican wolves were released into recovery areas in Arizona and New Mexico beginning in 1998 in order to assist the animals' recolonization of their former historical range.[6]

Taxonomy and evolution

First described as a distinct subspecies in 1929 by Edward Nelson and Edward Goldman on account of its small size, narrow skull and dark pelt,[7] genetic and morphological studies indicate that the Mexican wolf is the most basal and genetically distinct of North American gray wolves, being more closely related to Old World wolves rather than other New World subspecies.[4] Its ancestors were likely the first gray wolves to cross the Bering Land Bridge into North America during the Pleistocene after the extinction of the Beringian wolf,[8] colonizing most of the continent until pushed southwards by the newly arrived ancestors of C. l. nubilus.[4]

Hybridization with coyotes and red wolves

Unlike eastern wolves and red wolves, the gray wolf species rarely interbreeds with coyotes in the wild. Direct hybridizations between coyotes and gray wolves was never explicitly observed. Nevertheless, in a study that analyzed the molecular genetics of the coyotes as well as samples of historical red wolves and Mexican wolves from Texas, a few coyote genetic markers have been found in the historical samples of some isolated individual Mexican wolves. Likewise, gray wolf Y-chromosomes have also been found in a few individual male Texan coyotes.[9] This study suggested that although the Mexican gray wolf is generally less prone to hybridizations with coyotes compared to the red wolf, there may had been exceptional genetic exchanges with the Texan coyotes among a few individual gray wolves from historical remnants before the population was completely extirpated in Texas. However, the same study also countered that theory with an alternative possibility that it may have been the red wolves, who in turn also once overlapped with both species in the central Texas, who were involved in circuiting the gene-flows between the coyotes and gray wolves much like how the eastern wolf is suspected to have bridged gene-flows between gray wolves and coyotes in the Great Lakes region since direct hybridizations between coyotes and gray wolves is considered rare.

In tests performed on a sample from a taxidermied carcass of what was initially labelled as a chupacabra, mitochondrial DNA analysis conducted by Texas State University professor Michael Forstner showed that it was a coyote. However, subsequent analysis by a veterinary genetics laboratory team at the University of California, Davis concluded that, based on the sex chromosomes, the male animal was a coyote–wolf hybrid sired by a male Mexican wolf.[10][11] It has been suggested that the hybrid animal was afflicted with sarcoptic mange, which would explain its hairless and blueish appearance.[10]

History

The Mexican wolf was held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico, where it was considered a symbol of war and the Sun. In the city of Teotihuacan, it was common practice to crossbreed Mexican wolves with dogs to produce temperamental, but loyal, animal guardians. Wolves were also sacrificed in religious rituals, which involved quartering the animals and keeping their heads as attire for priests and warriors. The remaining body parts were deposited in underground funerary chambers with a westerly orientation, which symbolized rebirth, the Sun, the underworld and the canid god Xolotl.[5] The earliest written record of the Mexican wolf comes from Francisco Javier Clavijero's Historia de México in 1780, where it is referred to as Cuetzlachcojotl, and is described as being of the same species as the coyote, but with a more wolf-like pelt and a thicker neck.[12]

Decline

There was a rapid reduction of Mexican wolf populations in the Southwestern United States from 1915-1920; by the mid-1920s, livestock losses to Mexican wolves became rare in areas where the costs once ranged in the millions of dollars.[13] Vernon Bailey, writing in the early 1930s, noted that the highest Mexican wolf densities occurred in the open grazing areas of the Gila National Forest, and that wolves were completely absent in the lower Sonora. He estimated that there were 103 Mexican wolves in New Mexico in 1917, though the number had been reduced to 45 a year later. By 1927, it had apparently become extinct in New Mexico.[3] Sporadic encounters with wolves entering Texas, New Mexico and Arizona via Mexico continued through to the 1950s, until they too were driven away through traps, poison and guns. The last wild wolves to be killed in Texas were a male shot on December 5, 1970 on Cathedral Mountain Ranch and another caught in a trap on the Joe Neal Brown Ranch on December 28. Wolves were still being reported in small numbers in Arizona in the early 1970s, while accounts of the last wolf to be killed in New Mexico are difficult to evaluate, as all the purported "last wolves" could not be confirmed as genuine wolves rather than other canid species.[13]

The Mexican wolf persisted longer in Mexico, as human settlement, ranching and predator removal came later than in the Southwestern United States. Wolf numbers began to rapidly decline during the 1930s-1940s, when Mexican ranchers began adopting the same wolf-control methods as their American counterparts, relying heavily on the indiscriminate usage of 1080.[13]

Conservation and recovery

The Mexican wolf was listed as endangered under the Ecological Society of America in 1976, with the Mexican Wolf Recovery Team being formed three years later by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The Recovery Team composed the Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, which called for the reestablishment of at least 100 wolves in their historic range through a captive breeding program. Between 1977 to 1980, four males and a pregnant female were captured in Durango and Chihuahua in Mexico to act as founders of a new "certified lineage". By 1999, with the addition of new lineages, the captive Mexican wolf population throughout the US and Mexico reached 178 individuals. These captive-bred animals were subsequently released into the Apache National Forest in eastern Arizona, and allowed to recolonize east-central Arizona and south-central New Mexico, areas which were collectively termed the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area (BRWRA). The Recovery Plan called for the release of additional wolves in the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area in south-central New Mexico, should the goal of 100 wild wolves in the Blue Range area not be achieved.[6]

By late 2012, it was estimated that there were at least 75 wolves and four breeding pairs living in the recovery areas, with 27% of the population consisting of pups. Since 1998, 92 wolf deaths were recorded, with four occurring in 2012; these four were all due to illegal shootings.[14]

Releases have also been conducted in Mexico, and the first birth of a wild wolf litter in Mexico was reported in 2014.[15]

A study released by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in February 2015 shows a minimum population of 109 wolves in 2014 in southwest New Mexico and southeast Arizona, a 31 percent increase from 2013.[16]

According to a survey done on the population of the Mexican wolf in Alpine, Arizona, the recovery of the species is being negatively impacted due to poaching. In an effort to fight the slowing recovery, GPS monitoring devices are being used to monitor the wolves.[17]

Further reading

- Holaday, B. (2003), Return of the Mexican Gray Wolf: Back to the Blue, University of Arizona Press, ISBN 0816522960

- Shaw, H. (2002), The Wolf in the Southwest: The Making of an Endangered Species, High-Lonesome Books, ISBN 0944383599

See also

References

- ↑

- ↑ Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 350, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- 1 2 Bailey, V. (1932), Mammals of New Mexico. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Biological Survey. North American Fauna No. 53. Washington, D.C. Pages 303-308.

- 1 2 3 Chambers SM, Fain SR, Fazio B, Amaral M (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- 1 2 3 Valadez, R., Rodríguez, B., Manzanilla, L. & Tejeda, S. (2006), Dog-wolf hybrid biotype reconstruction from the archaeological city of Teotihuacan in prehispanic central Mexico, in Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction, ed. L. M. Snyder & E. A. Moore, pp. 121-131, Oxford, England: Oxbow Books (Proceedings of the 9th ICAZ Conference, Durham, England, 2002.

- 1 2 Nie, M. A. (2003), Beyond Wolves: The Politics of Wolf Recovery and Management, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 118-119, ISBN 0816639787

- ↑ Nelson, E. W. and Goldman, E. A. (1929), A new wolf from Mexico, Journal of Mammalogy 10:165–166.

- ↑ Leonard. J. A., Vilà, C., Fox-Dobbs. K., Koch, P. L., Wayne. R. K., Van Valkenburgh, G. (2007), Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph, Current Biology 17:1146–1150

- ↑ http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0003333

- 1 2 http://bionews-tx.com/news/2013/09/01/texas-state-university-researcher-helps-unravel-mystery-of-texas-blue-dog-claimed-to-be-chupacabra/

- ↑ http://www.victoriaadvocate.com/news/2008/oct/31/sl_chupa_12/

- ↑ Clavijero, Francisco Javier (1817) The history of Mexico, Volume 1, Thomas Dobson, p. 57

- 1 2 3 USFWS, (1982), Mexican wolf recovery plan, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- ↑ USFWS (2012), Mexican Wolf Recovery Program: Progress Report #15, US Fish and Wildlife Service

- ↑ Gannon, M. (2014-07-21). "First Litter of Wild Wolf Pups Born in Mexico". LiveScience.com. Purch. Archived from the original on 2014-07-23. Retrieved 2014-07-23. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ http://www.fws.gov/southwest/es/mexicanwolf/pdf/fNR_Mexican_Wolf_winter_count_joint_Feb13-2015.pdf

- ↑ http://www.usatoday.com/videos/news/nation/2016/01/28/79481264/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canis lupus baileyi. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Canis lupus baileyi |