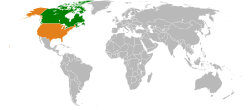

Canada–United States relations

|

|

Canada |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Canadian Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Ottawa |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Gary Doer | Ambassador Bruce Heyman |

Relations between Canada and the United States of America have spanned more than two centuries. This includes a shared British cultural heritage, and the development of one of the most stable and mutually-beneficial international relationships in the world. Each is the other's chief economic partner. Tourism and migration between the two nations have increased rapport. The U.S. is ten times larger in population and is by far the dominant partner in terms of cultural and economic influence. Starting with the American Revolution, a vocal element in Canada has warned against American dominance or annexation. The War of 1812 saw invasions across the border. In 1815, the war ended with the border unchanged and demilitarized, as were the Great Lakes. Furthermore, the British ceased aiding First Nation attacks on American territory, and the United States never again attempted to invade Canada. Apart from minor raids, it has remained peaceful.[1]

As Britain decided to disengage, fears of an American takeover played a role in the formation of the Dominion of Canada (1867), and Canada's rejection of free trade (1911). Military collaboration was close during World War II and continued throughout the Cold War on both a bilateral basis through NORAD and through multilateral participation in NATO. A very high volume of trade and migration continues between the two nations, as well as a heavy overlapping of popular and elite culture, a dynamic which has generated closer ties, especially after the signing of the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement in 1988.

Canada and the United States are currently the world's largest independently sovereign trading partners.[2] The two nations share the world's longest border,[3] and have significant interoperability within the defence sphere. Recent difficulties have included repeated trade disputes, environmental concerns, Canadian concern for the future of oil exports, and issues of illegal immigration and the threat of terrorism. Nevertheless, trade has continued to expand, especially following the 1988 FTA and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 which has further merged the two economies.[4][5]

The foreign policies of the neighbours have been closely aligned since the Cold War. However, Canada has disagreed with American policies regarding the Vietnam War, the status of Cuba, the Iraq War, Missile Defense, and the War on Terrorism. A diplomatic debate has been underway in recent years on whether the Northwest Passage is in international waters or under Canadian sovereignty.

According to Gallup's annual public opinion polls, Canada has consistently been Americans' favorite nation, with 96% of Americans viewing Canada favorably in 2012.[6][7] According to a 2013 BBC World Service Poll, 84% of Americans view their northern neighbor's influence positively, with only 5% expressing a negative view, the most favorable perception of Canada in the world. As of spring 2013, 64% of Canadians had a favorable view of the U.S. and 81% expressed confidence in Obama to do the right thing in international matters. According to the same poll, 30% viewed the U.S. negatively.[8] Also, according to a 2014 BBC World Service Poll, 86% of Americans view Canada's influence positively, with only 5% expressing a negative view. However, according to the same poll, 43% of Canadians view U.S. influence positively, with 52% expressing a negative view.[9]

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Populations | 322,097,703 (November 2015) (3rd)[10] | 35,540,619 (July 2014) (37th)[11] |

| Area | 9,857,306 km² (3,805,927 sq mi)[12] | 9,984,670 km² (3,854,085 sq mi) |

| Population density | 34.2/km² (87.4/sq mi) | 3.41/km² (8.3/sq mi) |

| Capital | Washington, D.C. | Ottawa |

| Largest city | New York City | Toronto |

| Government | Federal presidential constitutional republic | Federal parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy |

| First leader(s) | George Washington | Sir John A. Macdonald |

| Current leader | Barack Obama | Justin Trudeau |

| Official languages | None at federal level, but English de facto | English and French |

| Main religions | 78.4% Christian, 14.1% Unaffiliated, 1.7% Judaism, 0.7% Buddhism, 0.6% Islam, 0.4% Hinduism, 1.2% Other, 0.8% Don't Know/Refused Answer | 67.3% Christian, 3.2% Islam, 1.5% Hinduism, 1.4% Sikhism, 1.1% Buddhism, 1.0% Judaism |

| Human Development Index | 0.914 (very high) | 0.902 (very high) |

| GDP (nominal) (2014)[13] | $17.416 trillion ($54,390 per capita) | $1.793 trillion ($50,577 per capita) |

| GDP (PPP) (2014)[13] | $17.416 trillion ($54,390 per capita) | $1.578 trillion ($44,519 per capita) |

| Military expenditures | $600.4 billion (3.7% of GDP) | $14.4 billion (1.5% of GDP) |

History

Colonial wars

Before the British conquest of French Canada in 1760, there had been a series of wars between the British and the French which were fought out in the colonies as well as in Europe and the high seas. In general, the British heavily relied on American colonial militia units, while the French heavily relied on their First Nation allies. The Iroquois Nation were important allies of the British.[14] Much of the fighting involved ambushes and small-scale warfare in the villages along the border between New England and Quebec. The New England colonies had a much larger population than Quebec, so major invasions came from south to north. The First Nation allies, only loosely controlled by the French, repeatedly raided New England villages to kidnap women and children, and torture and kill the men.[15] Those who survived were brought up as Francophone Catholics. The tension along the border was exacerbated by religion, the French Catholics and English Protestants had a deep mutual distrust.[16] There was a naval dimension as well, involving privateers attacking enemy merchant ships.[17]

England seized Quebec from 1629 to 1632, and Acadia in 1613 and again from 1654 to 1670; These territories were returned to France by the peace treaties. The major wars were (to use American names), King William's War (1689–1697); Queen Anne's War (1702–1713); King George's War (1744–1748), and the French and Indian War (1755–1763). In Canada, as in Europe, this era is known as the Seven Years' War.

New England soldiers and sailors were critical to the successful British campaign to capture the French fortress of Louisbourg in 1745,[18] and (after it had been returned by treaty) to capture it again in 1758.[19]

Mingling of peoples

From the 1750s to the 21st century, there has been extensive mingling of the Canadian and American populations, with large movements in both directions.[20]

New England Yankees settled large parts of Nova Scotia before 1775, and were neutral during the American Revolution.[21] At the end of the Revolution, about 75,000 Loyalists moved out of the new United States to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the lands of Quebec, east and south of Montreal. From 1790 to 1812 many farmers moved from New York and New England into Ontario (mostly to Niagara, and the north shore of Lake Ontario). In the mid and late 19th century gold rushes attracted American prospectors, mostly to British Columbia (Cariboo, Fraser gold rushes) and later to the Yukon. In the early 20th century, the opening of land blocks in the Prairie Provinces attracted many farmers from the American Midwest. Many Mennonites immigrated from Pennsylvania and formed their own colonies. In the 1890s some Mormons went north to form communities in Alberta after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints rejected plural marriage.[22] The 1960s saw the arrival of about 50,000 draft-dodgers who opposed the Vietnam War.[23]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, about 900,000 French Canadians moved to the U.S., with 395,000 residents there in 1900. Two-thirds went to mill towns in New England, where they formed distinctive ethnic communities. By the late 20th century, they had abandoned the French language, but most kept the Catholic religion.[24] About twice as many English Canadians came to the U.S., but they did not form distinctive ethnic settlements.[25]

Canada was a way-station through which immigrants from other lands stopped for a while, ultimately heading to the U.S. In 1851–1951, 7.1 million people arrived in Canada (mostly from Continental Europe), and 6.6 million left Canada, most of them to the U.S.[26]

American Revolutionary War

At the outset of the American Revolutionary War, the American revolutionaries hoped the French Canadians in Quebec and the Colonists in Nova Scotia would join their rebellion and they were pre-approved for joining the United States in the Articles of Confederation. When Canada was invaded, thousands joined the American cause and formed regiments that fought during the war; however most remained neutral and some joined the British effort. Britain advised the French Canadians that the British Empire already enshrined their rights in the Quebec Act, which the American colonies had viewed as one of the Intolerable Acts. The American invasion was a fiasco and Britain tightened its grip on its northern possessions; in 1777, a major British invasion into New York led to the surrender of the entire British army at Saratoga, and led France to enter the war as an ally of the U.S. The French Canadians largely ignored France's appeals for solidarity.[27] After the war Canada became a refuge for about 75,000 Loyalists who either wanted to leave the U.S., or were compelled by Patriot reprisals to do so.[28]

Among the original Loyalists there were 3,500 free blacks. Most went to Nova Scotia and in 1792, 1200 migrated to Sierra Leone. About 2000 black slaves were brought in by Loyalist owners; they remained slaves in Canada until the Empire abolished slavery in 1833. Before 1860, about 30,000–40,000 blacks entered Canada; many were already free and others were escaped slaves who came through the Underground Railroad.[29]

War of 1812

The Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the war, called for British forces to vacate all their forts south of the Great Lakes border. Britain refused to do so, citing failure of the United States to provide financial restitution for Loyalists who had lost property in the war. The Jay Treaty in 1795 with Great Britain resolved that lingering issue and the British departed the forts. Thomas Jefferson saw the nearby British imperial presence as a threat to the United States, and so he opposed the Jay Treaty, and it became one of the major political issues in the United States at the time.[30] Thousands of Americans immigrated to Upper Canada (Ontario) from 1785 to 1812 to obtain cheaper land and better tax rates prevalent in that province; despite expectations that they would be loyal to the U.S. if a war broke out, in the event they were largely non-political.[31]

Tensions mounted again after 1805, erupting into the War of 1812, when the Americans declared war on Britain. The Americans were angered by British harassment of U.S. ships on the high seas and seizure ("Impressment") of 6,000 sailors from American ships, severe restrictions against neutral American trade with France, and British support for hostile Indian tribes in Ohio and territories the U.S. had gained in 1783. American "honor" was an implicit issue. The Americans were outgunned by more than 10 to 1 by the Royal Navy, but could call on an army much larger than the British garrison in Canada, and so a land invasion of Canada was proposed as the only feasible, and most advantegous means of attacking the British Empire. Americans on the western frontier also hoped an invasion would bring an end to British support of Native American resistance to the westward expansion of the United States, typified by Tecumseh's coalition of tribes.[32] Americans may also have wanted to annex Canada.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]

Once war broke out, the American strategy was to seize Canada—perhaps as a means of forcing concessions from the British Empire, or perhaps in order to annex it. There was some hope that settlers in western Canada—most of them recent immigrants from the U.S.—would welcome the chance to overthrow their British rulers. However, the American invasions were defeated primarily by British regulars with support from Native Americans and Upper Canada (Ontario) militia. Aided by the powerful Royal Navy, a series of British raids on the American coast were highly successful, culminating with an attack on Washington that resulted in the British burning of the White House, Capitol, and other public buildings. Major British invasions of New York in 1814 and Louisiana in 1814–15 were fiascoes, with the British retreating from New York and decisively defeated at the Battle of New Orleans. At the end of the war, Britain's American Indian allies had largely been defeated, and the Americans controlled a strip of Western Ontario centered on Fort Malden. However, Britain held much of Maine, and, with the support of their remaining American Indian allies, huge areas of the Old Northwest, including Wisconsin and much of Michigan and Illinois. With the surrender of Napoleon in 1814, Britain ended naval policies that angered Americans; with the defeat of the Indian tribes the threat to American expansion was ended. The upshot was both sides had asserted their honour, Canada was not annexed, and London and Washington had nothing more to fight over. The war was ended by the Treaty of Ghent, which took effect in February 1815.[41] A series of postwar agreements further stabilized peaceful relations along the Canadian-US border. Canada reduced American immigration for fear of undue American influence, and built up the Anglican church as a counterweight to the largely American Methodist and Baptist churches.[42]

In later years, Anglophone Canadians, especially in Ontario, viewed the War of 1812 as a heroic and successful resistance against invasion and as a victory that defined them as a people. The myth that the Canadian militia had defeated the invasion almost single-handed, known logically as the "militia myth", became highly prevalent after the war, having been propounded by John Strachan, Anglican Bishop of York. Meanwhile, the United States celebrated victory in its "Second War of Independence," and war heroes such as Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison headed to the White House.[43]

Conservative reaction

In the aftermath of the War of 1812, pro-imperial conservatives led by Anglican Bishop John Strachan took control in Ontario ("Upper Canada"), and promoted the Anglican religion as opposed to the more republican Methodist and Baptist churches. A small interlocking elite, known as the Family Compact took full political control. Democracy, as practiced in the US, was ridiculed. The policies had the desired effect of deterring immigration from United States. Revolts in favor of democracy in Ontario and Quebec ("Lower Canada") in 1837 were suppressed; many of the leaders fled to the US.[44] The American policy was to largely ignore the rebellions,[45] and indeed ignore Canada generally in favor of westward expansion of the American Frontier.

Alabama claims

At the end of the American Civil War in 1865, Americans were angry at British support for the Confederacy. One result was toleration of Fenian efforts to use the U.S. as a base to attack Canada. More serious was the demand for a huge payment to cover the damages caused, on the notion that British involvement had lengthened the war. Senator Charles Sumner, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, originally wanted to ask for $2 billion, or alternatively the ceding of all of Canada to the United States.[46] When American Secretary of State William H. Seward negotiated the Alaska Purchase with Russia in 1867, he intended it as the first step in a comprehensive plan to gain control of the entire northwest Pacific Coast. Seward was a firm believer in Manifest Destiny, primarily for its commercial advantages to the U.S. Seward expected British Columbia to seek annexation to the U.S. and thought Britain might accept this in exchange for the Alabama claims. Soon other elements endorsed annexation, Their plan was to annex British Columbia, Red River Colony (Manitoba), and Nova Scotia, in exchange for the dropping the damage claims. The idea reached a peak in the spring and summer of 1870, with American expansionists, Canadian separatists, and British anti-imperialists seemingly combining forces. The plan was dropped for multiple reasons. London continued to stall, American commercial and financial groups pressed Washington for a quick settlement of the dispute on a cash basis, growing Canadian nationalist sentiment in British Columbia called for staying inside the British Empire, Congress became preoccupied with Reconstruction, and most Americans showed little interest in territorial expansion. The "Alabama Claims" dispute went to international arbitration. In one of the first major cases of arbitration, the tribunal in 1872 supported the American claims and ordered Britain to pay $15.5 million. Britain paid and the episode ended in peaceful relations.[47][48]

Dominion of Canada

Canada became a self-governing dominion in 1867 in internal affairs while Britain controlled diplomacy and defense policy. Prior to Confederation, there was an Oregon boundary dispute in which the Americans claimed the 54th degree latitude. That issue was resolved by splitting the disputed territory; the northern half became British Columbia, and the southern half the states of Washington and Oregon. Strained relations with America continued, however, due to a series of small-scale armed incursions named the Fenian raids by Irish-American Civil War veterans across the border from 1866 to 1871 in an attempt to trade Canada for Irish independence.[49] The American government, angry at Canadian tolerance of Confederate raiders during the American Civil War, moved very slowly to disarm the Fenians. The British government, in charge of diplomatic relations, protested cautiously, as Anglo-American relations were tense. Much of the tension was relieved as the Fenians faded away and in 1872 by the settlement of the Alabama Claims, when Britain paid the U.S. $15.5 million for war losses caused by warships built in Britain and sold to the Confederacy.

Disputes over ocean boundaries on Georges Bank and over fishing, whaling, and sealing rights in the Pacific were settled by international arbitration, setting an important precedent.[50]

Emigration to and from the United States

After 1850, the pace of industrialization and urbanization was much faster in the United States, drawing a wide range of immigrants from the North. By 1870, 1/6 of all the people born in Canada had moved to the United States, with the highest concentrations in New England, which was the destination of Francophone emigrants from Quebec and Anglophone emigrants from the Maritimes. It was common for people to move back and forth across the border, such as seasonal lumberjacks, entrepreneurs looking for larger markets, and families looking for jobs in the textile mills that paid much higher wages than in Canada.[51]

The southward migration slacked off after 1890, as Canadian industry began a growth spurt. By then, the American frontier was closing, and thousands of farmers looking for fresh land moved from the United States north into the Prairie Provinces. The net result of the flows were that in 1901 there were 128,000 American-born residents in Canada (3.5% of the Canadian population) and 1.18 million Canadian-born residents in the United States (1.6% of the U.S. population).[52]

Alaska boundary

A short-lived controversy was the Alaska boundary dispute, settled in favor of the United States in 1903. No one cared until a gold rush brought tens of thousands of men to Canada's Yukon, and they had to arrive through American ports. Canada needed its port and claimed that it had a legal right to a port near the present American town of Haines, Alaska. It would provide an all-Canadian route to the rich goldfields. The dispute was settled by arbitration, and the British delegate voted with the Americans—to the astonishment and disgust of Canadians who suddenly realized that Britain considered its relations with the United States paramount compared to those with Canada. The arbitrartion validated the status quo, but made Canada angry at Britain.[53]

1907 saw a minor controversy over USS Nashville sailing into the Great Lakes via Canada without Canadian permission. To head off future embarrassments, in 1909 the two sides signed the International Boundary Waters Treaty and the International Joint Commission was established to manage the Great Lakes and keep them disarmed. It was amended in World War II to allow the building and training of warships.[54]

Reciprocal trade with U.S.

Anti-Americanism reached a shrill peak in 1911 in Canada.[55] The Liberal government in 1911 negotiated a Reciprocity treaty with the U.S. that would lower trade barriers. Canadian manufacturing interests were alarmed that free trade allow the bigger and more efficient American factories to take their markets. The Conservatives made it a central campaign issue in the 1911 election, warning that it would be a "sell out" to the United States with economic annexation a special danger.[56] Conservative slogan was "No truck or trade with the Yankees", as they appealed to Canadian nationalism and nostalgia for the British Empire to win a major victory.[57]

Canadian autonomy

Canada demanded and received permission from London to send its own delegation to the Versailles Peace Talks in 1919, with the proviso that it sign the treaty under the British Empire. Canada subsequently took responsibility for its own foreign and military affairs in the 1920s. Its first ambassador to the United States, Vincent Massey, was named in 1927. The United States first ambassador to Canada was William Phillips. Canada became an active member of the British Commonwealth, the League of Nations, and the World Court, none of which included the U.S.

Relations with the United States were cordial until 1930, when Canada vehemently protested the new Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act by which the U.S. raised tariffs (taxes) on products imported from Canada. Canada retaliated with higher tariffs of its own against American products, and moved toward more trade within the British Commonwealth. U.S.–Canadian trade fell 75% as the Great Depression dragged both countries down.[58][59]

Down to the 1920s the war and naval departments of both nations designed hypothetical war game scenarios with the other as an enemy. These were primarily exercises; the departments were never told to get ready for a real war. In 1921, Canada developed Defence Scheme No. 1 for an attack on American cities and for forestalling invasion by the United States until Imperial reinforcements arrived. Through the later 1920s and 1930s, the United States Army War College developed a plan for a war with the British Empire waged largely on North American territory, in War Plan Red.[60]

Herbert Hoover meeting in 1927 with British Ambassador Sir Esme Howard agreed on the "absurdity of contemplating the possibility of war between the United States and the British Empire."[61]

In 1938, as the roots of World War II were set in motion, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt gave a public speech at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, declaring that the United States would not sit idly by if another power tried to dominate Canada. Diplomats saw it as a clear warning to Germany not to attack Canada.[62]

World War II

The two nations cooperated closely in World War II,[63] as both nations saw new levels of prosperity and a determination to defeat the Axis powers. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and President Franklin D. Roosevelt were determined not to repeat the mistakes of their predecessors.[64] They met in August 1940 at Ogdensburg, issuing a declaration calling for close cooperation, and formed the Permanent Joint Board on Defense (PJBD).

King sought to raise Canada's international visibility by hosting the August 1943 Quadrant conference in Quebec on military and political strategy; he was a gracious host but was kept out of the important meetings by Winston Churchill and Roosevelt.

Canada allowed the construction of the Alaska Highway and participated in the building of the atomic bomb. 49,000 Americans joined the RCAF (Canadian) or RAF (British) air forces through the Clayton Knight Committee, which had Roosevelt's permission to recruit in the U.S. in 1940–42.[65]

American attempts in the mid-1930s to integrate British Columbia into a united West Coast military command had aroused Canadian opposition. Fearing a Japanese invasion of Canada's vulnerable coast, American officials urged the creation of a united military command for an eastern Pacific Ocean theater of war. Canadian leaders feared American imperialism and the loss of autonomy more than a Japanese invasion. In 1941, Canadians successfully argued within the PJBD for mutual cooperation rather than unified command for the West Coast.[66]

Newfoundland

The United States built large military bases in Newfoundland, at the time, a British dominion. The American involvement ended the depression and brought new prosperity; Newfoundland's business community sought closer ties with the United States as expressed by the Economic Union Party. Ottawa took notice and wanted Newfoundland to join Canada, which it did after hotly contested referenda. There was little demand in the United States for the acquisition of Newfoundland, so the United States did not protest the British decision not to allow an American option on the Newfoundland referendum.[67]

Cold War

Following co-operation in the two World Wars, Canada and the United States lost much of their previous animosity. As Britain's influence as a global imperial power declined, Canada and the United States became extremely close partners. Canada was a close ally of the United States during the Cold War.

Nixon Shock 1971

The United States had become Canada's largest market, and after the war the Canadian economy became dependent on smooth trade flows with the United States so much that in 1971 when the United States enacted the "Nixon Shock" economic policies (including a 10% tariff on all imports) it put the Canadian government into a panic. This led in a large part to the articulation of Prime Minister Trudeau's "Third Option" policy of diversifying Canada's trade and downgrading the importance of Canada – United States relations. In a 1972 speech in Ottawa, Nixon declared the "special relationship" between Canada and the United States dead.[68]

1990s

The main issues in Canada–U.S. relations in the 1990s focused on the NAFTA agreement, which was signed in 1994. It created a common market that by 2014 was worth $19 trillion, encompassed 470 million people, and had created millions of jobs.[69] Wilson says, "Few dispute that NAFTA has produced large and measurable gains for Canadian consumers, workers, and businesses." However, he adds, "NAFTA has fallen well short of expectations."[70]

Anti-Americanism

Since the arrival of the Loyalists as refugees from the American Revolution in the 1780s, historians have identified a constant theme of Canadian fear of the United States and of "Americanization" or a cultural takeover. In the War of 1812, for example, the enthusiastic response by French militia to defend Lower Canada reflected, according to Heidler and Heidler (2004), "the fear of Americanization."[71] Scholars have traced this attitude over time in Ontario and Quebec.[72]

Canadian intellectuals who wrote about the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century identified America as the world center of modernity, and deplored it. Imperialists (who admired the British Empire) explained that Canadians had narrowly escaped American conquest with its rejection of tradition, its worship of "progress" and technology, and its mass culture; they explained that Canada was much better because of its commitment to orderly government and societal harmony. There were a few ardent defenders of the nation to the south, notably liberal and socialist intellectuals such as F. R. Scott and Jean-Charles Harvey (1891–1967).[73]

Looking at television, Collins (1990) finds that it is in English Canada that fear of cultural Americanization is most powerful, for there the attractions of the U.S. are strongest.[74] Meren (2009) argues that after 1945, the emergence of Quebec nationalism and the desire to preserve French-Canadian cultural heritage led to growing anxiety regarding American cultural imperialism and Americanization.[75] In 2006 surveys showed that 60 percent of Quebecers had a fear of Americanization, while other surveys showed they preferred their current situation to that of the Americans in the realms of health care, quality of life as seniors, environmental quality, poverty, educational system, racism and standard of living. While agreeing that job opportunities are greater in America, 89 percent disagreed with the notion that they would rather be in the United States, and they were more likely to feel closer to English Canadians than to Americans.[76] However, there is evidence that the elites and Quebec are much less fearful of Americanization, and much more open to economic integration than the general public.[76]

The history has been traced in detail by a leading Canadian historian J.L. Granatstein in Yankee Go Home: Canadians and Anti-Americanism (1997). Current studies report the phenomenon persists. Two scholars report, "Anti-Americanism is alive and well in Canada today, strengthened by, among other things, disputes related to NAFTA, American involvement in the Middle East, and the ever-increasing Americanization of Canadian culture."[77] Jamie Glazov writes, "More than anything else, Diefenbaker became the tragic victim of Canadian anti-Americanism, a sentiment the prime minister had fully embraced by 1962. [He was] unable to imagine himself (or his foreign policy) without enemies."[78] Historian J. M. Bumsted says, "In its most extreme form, Canadian suspicion of the United States has led to outbreaks of overt anti-Americanism, usually spilling over against American residents in Canada."[79] John R. Wennersten writes, "But at the heart of Canadian anti-Americanism lies a cultural bitterness that takes an American expatriate unaware. Canadians fear the American media's influence on their culture and talk critically about how Americans are exporting a culture of violence in its television programming and movies."[80] However Kim Nossal points out that the Canadian variety is much milder than anti-Americanism in some other countries.[81] By contrast Americans show very little knowledge or interest one way or the other regarding Canadian affairs.[82] Canadian historian Frank Underhill, quoting Canadian playwright Merrill Denison summed it up: "Americans are benevolently ignorant about Canada, whereas Canadians are malevolently informed about the United States."[83]

Relations between political executives

The executive of each country is represented differently. The President of the United States serves as both the head of state and head of government, and his "administration" is the executive, while the Prime Minister of Canada is head of government only, and his or her "government" or "ministry" directs the executive.

Mulroney and Reagan

Relations between Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan were famously close. This relationship resulted in negotiations on a potential free trade agreement, and a treaty of acid-rain-causing emissions, both major policy goals of Mulroney, that would be finalized under the presidency of George H. W. Bush.

Chrétien and Clinton

Although Jean Chrétien was wary to appearing too close to the president, personally, he and Bill Clinton were known to be golfing partners. Their governments had many small trade quarrels over magazines, softwood lumber, and so on, but on the whole were quite friendly. Both leaders had run on reforming or abolishing NAFTA, but the agreement went ahead with the addition of environmental and labor side agreements. Crucially, the Clinton administration lent rhetorical support to Canadian unity during the 1995 referendum in Quebec on independence from Canada.

Bush and Chrétien

Relations between Chrétien and George W. Bush were strained throughout their overlapping times in office. Jean Chrétien publicly mused that U.S. foreign policy might be part of the "root causes" of terrorism shortly after September 11 attacks. Some Americans did not appreciate his "smug moralism", and Chrétien's public refusal to support the 2003 Iraq war was met with chagrin in the United States, especially among conservatives.[84]

Bush and Harper

Stephen Harper and George W. Bush were thought to share warm personal relations and also close ties between their administrations. Because Bush was so unpopular in Canada, however, this was rarely emphasized by the Harper government.[85]

Shortly after being congratulated by Bush for his victory in February 2006, Harper rebuked U.S. ambassador to Canada David Wilkins for criticizing the Conservatives' plans to assert Canada's sovereignty over the Arctic Ocean waters with military force.

Harper and Obama

President Barack Obama's first international trip was to Canada on February 19, 2009.[86] Aside from Canadian lobbying against "Buy American" provisions in the U.S. stimulus package, relations between the two administrations have been smooth.

They have also held friendly bets on hockey games during the Winter Olympic season. In the 2010 Winter Olympics hosted by Canada in Vancouver, Canada defeated the US in both gold medal matches, allowing Stephen Harper to receive a case of Molson Canadian beer from Barack Obama, in reverse, if Canada lost, Harper would provide a case of Yuengling beer to Obama.[87] During the 2014 Winter Olympics, alongside U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry & Minister of Foreign Affairs John Baird, Stephen Harper was given a case of Samuel Adams beer by Obama for the Canadian gold medal victory over the US in women's hockey, and the semi-final victory over the US in men's hockey.[88]

Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC) (2011)

On February 4, 2011, Harper and Obama issued a "Declaration on a Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Economic Competitiveness"[89][90] and announced the creation of the Canada–United States Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC) "to increase regulatory transparency and coordination between the two countries."[91]

Health Canada and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the RCC mandate, undertook the "first of its kind" initiative by selecting "as its first area of alignment common cold indications for certain over-the-counter antihistamine ingredients (GC 2013-01-10)."[92]

On Wednesday, December 7, Harper flew to Washington to meet with Obama and sign an agreement to implement the joint action plans that had been developed since the initial meeting in February. The plans called on both countries to spend more on border infrastructure, share more information on people who cross the border, and acknowledge more of each other's safety and security inspection on third-country traffic. An editorial in The Globe and Mail praised the agreement for giving Canada the ability to track whether failed refugee claimants have left Canada via the U.S. and for eliminating "duplicated baggage screenings on connecting flights".[93] The agreement is not a legally-binding treaty, and relies on the political will and ability of the executives of both governments to implement the terms of the agreement. These types of executive agreements are routine—on both sides of the Canada–U.S. border.

Obama and Trudeau

President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau first met formally at the APEC summit meeting in Manila, Philippines in November 2015, nearly a week after the latter was sworn into the office. Both leaders expressed their eagerness for increased cooperation and coordination between the two countries during the course of Trudeau's government with Trudeau promising an "enhanced Canada–U.S. partnership".[94]

On November 6, 2015, Obama announced the U.S. State Department's rejection of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, the fourth phase of the Keystone oil pipeline system running between Canada and the United States, to which Trudeau expressed disappointment but said that the rejection would not damage Canada–U.S. relations and would instead provide a "fresh start" to strengthening ties through cooperation and coordination, saying that "the Canada–U.S. relationship is much bigger than any one project."[95] Obama has since praised Trudeau's efforts to prioritize the reduction of climate change, calling it "extraordinarily helpful" to establish a worldwide consensus on addressing the issue.[96]

Although Trudeau has told Obama his plans to withdraw Canada's McDonnell Douglas CF-18 Hornet jets assisting in the American-led intervention against ISIL, Trudeau said that Canada will still "do more than its part" in combating the terrorist group by increasing the number of Canadian special forces members training and fighting on ground in Iraq and Syria.[97]

Obama has invited Trudeau to the White House for an official visit and state dinner scheduled for March 10, 2016.[98]

Military and security

_January_2013.jpg)

The Canadian military, like forces of other NATO countries, fought alongside the United States in most major conflicts since World War II, including the Korean War, the Gulf War, the Kosovo War, and most recently the war in Afghanistan. The main exceptions to this were the Canadian government's opposition to the Vietnam War and the Iraq War, which caused some brief diplomatic tensions. Despite these issues, military relations have remained close.

American defense arrangements with Canada are more extensive than with any other country.[99] The Permanent Joint Board of Defense, established in 1940, provides policy-level consultation on bilateral defense matters. The United States and Canada share North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) mutual security commitments. In addition, American and Canadian military forces have cooperated since 1958 on continental air defense within the framework of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). Canadian forces have provided indirect support for the American invasion of Iraq that began in 2003.[100] Moreover, interoperability with the American armed forces has been a guiding principle of Canadian military force structuring and doctrine since the end of the Cold War. Canadian navy frigates, for instance, integrate seamlessly into American carrier battle groups.[101]

In commemoration of the 200th Anniversary of the War of 1812 ambassadors from Canada and the US, and naval officers from both countries gathered at the Pritzker Military Library on August 17, 2012, for a panel discussion on Canada-US relations with emphasis on national security-related matters. Also as part of the commemoration, the navies of both countries sailed together throughout the Great Lakes region.[102]

War in Afghanistan

Canada's elite JTF2 unit joined American special forces in Afghanistan shortly after the al-Qaida attacks on September 11, 2001. Canadian forces joined the multinational coalition in Operation Anaconda in January 2002. On April 18, 2002, an American pilot bombed Canadian forces involved in a training exercise, killing four and wounding eight Canadians. A joint American-Canadian inquiry determined the cause of the incident to be pilot error, in which the pilot interpreted ground fire as an attack; the pilot ignored orders that he felt were "second-guessing" his field tactical decision.[103][104] Canadian forces assumed a six-month command rotation of the International Security Assistance Force in 2003; in 2005, Canadians assumed operational command of the multi-national Brigade in Kandahar, with 2,300 troops, and supervises the Provincial Reconstruction Team in Kandahar, where al-Qaida forces are most active. Canada has also deployed naval forces in the Persian Gulf since 1991 in support of the UN Gulf Multinational Interdiction Force.[105]

The Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC maintains a public relations web site named CanadianAlly.com, which is intended "to give American citizens a better sense of the scope of Canada's role in North American and Global Security and the War on Terror".

The New Democratic Party and some recent Liberal leadership candidates have expressed opposition to Canada's expanded role in the Afghan conflict on the ground that it is inconsistent with Canada's historic role (since the Second World War) of peacekeeping operations.[106]

2003 Invasion of Iraq

According to contemporary polls, 71% of Canadians were opposed to the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[107] Many Canadians, and the former Liberal Cabinet headed by Paul Martin (as well as many Americans such as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama),[108] made a policy distinction between conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, unlike the Bush Doctrine, which linked these together in a "Global war on terror".

Trade

Canada and the United States have the world's largest trading relationship, with huge quantities of goods and people flowing across the border each year. Since the 1987 Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement, there have been no tariffs on most goods passed between the two countries.

In the course of the softwood lumber dispute, the U.S. has placed tariffs on Canadian softwood lumber because of what it argues is an unfair Canadian government subsidy, a claim which Canada disputes. The dispute has cycled through several agreements and arbitration cases. Other notable disputes include the Canadian Wheat Board, and Canadian cultural "restrictions" on magazines and television (See CRTC, CBC, and National Film Board of Canada). Canadians have been criticized about such things as the ban on beef since a case of Mad Cow disease was discovered in 2003 in cows from the United States (and a few subsequent cases) and the high American agricultural subsidies. Concerns in Canada also run high over aspects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) such as Chapter 11.[109]

Environmental issues

A principal instrument of this cooperation is the International Joint Commission (IJC), established as part of the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 to resolve differences and promote international cooperation on boundary waters. The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1972 is another historic example of joint cooperation in controlling trans-border water pollution.[110] However, there have been some disputes. Most recently, the Devil's Lake Outlet, a project instituted by North Dakota, has angered Manitobans who fear that their water may soon become polluted as a result of this project.

Beginning in 1986 the Canadian government of Brian Mulroney began pressing the Reagan administration for an "Acid Rain Treaty" in order to do something about U.S. industrial air pollution causing acid rain in Canada. The Reagan administration was hesitant, and questioned the science behind Mulroney's claims. However, Mulroney was able to prevail. The product was the signing and ratification of the Air Quality Agreement of 1991 by the first Bush administration. Under that treaty, the two governments consult semi-annually on trans-border air pollution, which has demonstrably reduced acid rain, and they have since signed an annex to the treaty dealing with ground level ozone in 2000.[111][112][113][114] Despite this, trans-border air pollution remains an issue, particularly in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed during the summer. The main source of this trans-border pollution results from coal-fired power stations, most of them located in the Midwestern United States.[115] As part of the negotiations to create NAFTA, Canada and the U.S. signed, along with Mexico, the North American Agreement On Environmental Cooperation which created the Commission for Environmental Cooperation which monitors environmental issues across the continent, publishing the North American Environmental Atlas as one aspect of its monitoring duties.[116]

Currently neither of the countries' governments support the Kyoto Protocol, which set out time scheduled curbing of greenhouse gas emissions. Unlike the United States, Canada has ratified the agreement. Yet after ratification, due to internal political conflict within Canada, the Canadian government does not enforce the Kyoto Protocol, and has received criticism from environmental groups and from other governments for its climate change positions. In January 2011, the Canadian minister of the environment, Peter Kent, explicitly stated that the policy of his government with regards to greenhouse gas emissions reductions is to wait for the United States to act first, and then try to harmonize with that action - a position that has been condemned by environmentalists and Canadian nationalists, and as well as scientists and government think-tanks.[117][118]

Newfoundland fisheries dispute

The United States and Britain, had a long-standing dispute about the rights of Americans fishing in the waters near Newfoundland.[119] Before 1776, there was no question that American fishermen, mostly from Massachusetts, had rights to use the waters off Newfoundland. In the peace treaty negotiations of 1783, the Americans insisted on a statement of these rights. However, France, an American ally, disputed the American position because France had its own specified rights in the area and wanted them to be exclusive.[120] The Treaty of Paris (1783) gave the Americans not rights, but rather "liberties" to fish within the territorial waters of British North America and to dry fish on certain coasts.

After the War of 1812, the Convention of 1818 between the United States and Britain specified exactly what liberties were involved.[121] Canadian and Newfoundland fishermen nevertheless contested these liberties in the 1830s and 1840s. The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, and the Treaty of Washington of 1871 spelled-out the liberties in more detail. However the Treaty of Washington expired in 1885, and there was a continuous round of disputes over jurisdictions and liberties. Britain the United States sent the issue to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 1909. It produced a compromise settlement that permanently ended the problems.[122][123]

Illicit drugs

In 2003 the American government became concerned when members of the Canadian government announced plans to decriminalize marijuana. David Murray, an assistant to U.S. Drug Czar John P. Walters, said in a CBC interview that, "We would have to respond. We would be forced to respond."[124] However the election of the Conservative Party in early 2006 halted the liberalization of marijuana laws for the foreseeable future.

A 2007 joint report by American and Canadian officials on cross-border drug smuggling indicated that, despite their best efforts, "drug trafficking still occurs in significant quantities in both directions across the border. The principal illicit substances smuggled across our shared border are MDMA (Ecstasy), cocaine, and marijuana."[125] The report indicated that Canada was a major producer of Ecstasy and marijuana for the U.S. market, while the U.S. was a transit country for cocaine entering Canada.

Diplomacy

Views of presidents and prime ministers

Presidents and prime ministers typically make formal or informal statements that indicate the diplomatic policy of their administration. Diplomats and journalists at the time—and historians since—dissect the nuances and tone to detect the warmth or coolness of the relationship.

- Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, speaking at the beginning of the 1891 election (fought mostly over Canadian free trade with the United States), arguing against closer trade relations with the U.S. stated "As for myself, my course is clear. A British subject I was born—a British subject I will die. With my utmost effort, with my latest breath, will I oppose the ‘veiled treason’ which attempts by sordid means and mercenary proffers to lure our people from their allegiance." (February 3, 1891.[126])

Canada's first Prime Minister also said:

It has been said that the United States Government is a failure. I don't go so far. On the contrary, I consider it a marvelous exhibition of human wisdom. It was as perfect as human wisdom could make it, and under it the American States greatly prospered until very recently; but being the work of men it had its defects, and it is for us to take advantage by experience, and endeavor to see if we cannot arrive by careful study at such a plan as will avoid the mistakes of our neighbors. In the first place we know that every individual state was an individual sovereignty—that each had its own army and navy and political organization - and when they formed themselves into a confederation they only gave the central authority certain specific rights appertaining to sovereign powers. The dangers that have risen from this system we will avoid if we can agree upon forming a strong central government—a great Central Legislature—a constitution for a Union which will have all the rights of sovereignty except those that are given to the local governments. Then we shall have taken a great step in advance of the American Republic. (September 12, 1864)

- Prime Minister John Sparrow Thompson, angry at failed trade talks in 1888, privately complained to his wife, Lady Thompson, that "These Yankee politicians are the lowest race of thieves in existence."[127]

- After the World War II years of close military and economic cooperation, President Harry S. Truman said in 1947 that "Canada and the United States have reached the point where we can no longer think of each other as 'foreign' countries."[128]

- President John F. Kennedy told Parliament in Ottawa in May 1961 that "Geography has made us neighbors. History has made us friends. Economics has made us partners. And necessity has made us allies. Those whom nature hath so joined together, let no man put asunder."[129]

- President Lyndon Johnson helped open Expo '67 with an upbeat theme, saying that "We of the United States consider ourselves blessed. We have much to give thanks for. But the gift of providence we cherish most is that we were given as our neighbours on this wonderful continent the people and the nation of Canada." Remarks at Expo '67, Montreal, May 25, 1967.[130]

|

Trudeau Washington Press Club speech

Trudeau's famous "sleeping with an elephant" quotation |

- Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau famously said that being America's neighbour "is like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered the beast, if one can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt."[131][132]

- Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, sharply at odds with the U.S. over Cold War policy, warned at a press conference in 1971 that the overwhelming American presence posed "a danger to our national identity from a cultural, economic and perhaps even military point of view."[133]

- President Richard Nixon, in a speech to Parliament in 1972 was angry at Trudeau, declared that the "special relationship" between Canada and the United States was dead. "It is time for us to recognize," he stated, "that we have very separate identities; that we have significant differences; and that nobody's interests are furthered when these realities are obscured."[134]

- In late 2001, President George W. Bush did not mention Canada during a speech in which he thanked a list of countries who had assisted in responding to the events of September 11, although Canada had provided military, financial, and other support.[135]

- Prime Minister Stephen Harper, in a statement congratulating Barack Obama on his inauguration, stated that "The United States remains Canada’s most important ally, closest friend and largest trading partner and I look forward to working with President Obama and his administration as we build on this special relationship."[136]

- President Barack Obama, speaking in Ottawa at his first official international visit in February 19, 2009, said, "I love this country. We could not have a better friend and ally."[137]

Territorial disputes

These include maritime boundary disputes:

- Dixon Entrance

- Beaufort Sea

- Strait of Juan de Fuca

- San Juan Islands

- Machias Seal Island and North Rock

Territorial land disputes:

- Aroostook War (Maine boundary)

- Alaska Boundary Dispute

- Pig War

and disputes over the international status of the:

Arctic disputes

A long-simmering dispute between Canada and the U.S. involves the issue of Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage (the sea passages in the Arctic). Canada’s assertion that the Northwest Passage represents internal (territorial) waters has been challenged by other countries, especially the U.S., which argue that these waters constitute an international strait (international waters). Canadians were alarmed when Americans drove the reinforced oil tanker Manhattan through the Northwest Passage in 1969, followed by the icebreaker Polar Sea in 1985, which actually resulted in a minor diplomatic incident. In 1970, the Canadian parliament enacted the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act, which asserts Canadian regulatory control over pollution within a 100-mile zone. In response, the United States in 1970 stated, "We cannot accept the assertion of a Canadian claim that the Arctic waters are internal waters of Canada. ... Such acceptance would jeopardize the freedom of navigation essential for United States naval activities worldwide." A compromise of sorts was reached in 1988, by an agreement on "Arctic Cooperation," which pledges that voyages of American icebreakers "will be undertaken with the consent of the Government of Canada." However the agreement did not alter either country's basic legal position. Paul Cellucci, the American ambassador to Canada, in 2005 suggested to Washington that it should recognize the straits as belonging to Canada. His advice was rejected and Harper took opposite positions. The U.S. opposes Harper's proposed plan to deploy military icebreakers in the Arctic to detect interlopers and assert Canadian sovereignty over those waters.[138][139]

Common memberships

| UKUSA Community |

|---|

|

Canada and the United States both hold membership in a number of multinational organizations such as:

- Arctic Council

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- Food and Agriculture Organization

- G7

- G-10

- G-20 major economies

- International Chamber of Commerce

- International Development Association

- International Monetary Fund

- International Olympic Committee

- Interpol

- MLB

- NBA

- NHL

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- North American Aerospace Defense Command

- North American Numbering Plan

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- Organization of American States

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America

- UKUSA Community

- United Nations

- UNESCO

- World Health Organization

- World Trade Organization

- World Bank

Diplomatic missions

Canadian missions in the United States

Canada's chief diplomatic mission to the United States is the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C.. It is further supported by many consulates located through United States.[140] The Canadian Government maintains consulates-general in several major U.S. cities including: Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, New York City, San Francisco and Seattle.

There are also Canadian trade offices located in Houston, Palo Alto and San Diego.

U.S. missions in Canada

The United States's chief diplomatic mission to Canada is the United States Embassy in Ottawa. It is further supported by many consulates located throughout Canada.[141] The U.S government maintains consulates-general in several major Canadian cities including: Calgary, Halifax, Montreal, Quebec City, Toronto, Vancouver and Winnipeg.

The United States also maintains Virtual Presence Posts (VPP) in the: Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Southwestern Ontario and Yukon.

See also

- Comparison of Canadian and American economies

- Continental One Highway

- Definitions of Canadian borders

- Etiquette in Canada and the United States

- Foreign relations of Canada

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Garrison mentality

- Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America

- United States Border Patrol interior checkpoints

References

- ↑ John Herd Thompson, Canada and the United States: ambivalent allies (2008).

- ↑ See 2009 data

- ↑ "The world's longest border". Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ↑ Hills, Carla A. "NAFTA's Economic Upsides: The View from the United States." Foreign Affairs 93 (2014): 122.

- ↑ Michael Wilson, "NAFTA's Unfinished Business: The View from Canada." Foreign Affairs (2014) 93#1 pp: 128+.

- ↑ "In U.S., Canada Places First in Image Contest; Iran Last". Gallup.com. February 19, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2011. published in 2010.

- ↑ Americans Give Record-High Ratings to Several U.S. Allies Gallup

- ↑ See Jacob Poushter and Bruce Drake, "Americans’ views of Mexico, Canada diverge as Obama attends ‘Three Amigos’ summit" '['Pew research Center February 19, 2014

- ↑ see 2014 poll

- ↑ "U.S. & World Population Clocks". Us Census Bureau. May 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Canada's population clock". Statistics Canada. August 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ↑ "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- 1 2 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/02/weodata/weoselco.aspx?g=2001&sg=All+countries. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Thomas Morgan, William (1926). "The Five Nations and Queen Anne". Mississippi Valley Historical Review 13 (2): 169–189. doi:10.2307/1891955. JSTOR 1891955.

- ↑ June Namias, White Captives: Gender and Ethnicity on the American Frontier (1993)

- ↑ Howard H. Peckham, The Colonial Wars (1965)

- ↑ Chard, Donald F. (1975). "The Impact of French Privateering on New England, 1689–1713". American Neptune 35 (3): 153–165.

- ↑ Shortt, S. E. D. (1972). "Conflict and Identity in Massachusetts: The Louisbourg Expedition of 1745". Social History / Histoire Sociale 5 (10): 165–185.

- ↑ Johnston, A. J. B. (2008). "D-Day at Louisbourg". Beaver 88 (3): 16–23.

- ↑ Marcus Lee Hansen, The Mingling of the Canadian and American Peoples. Vol. 1: Historical (1940)

- ↑ John Brebner, The Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia: A Marginal Colony During the Revolutionary Years (1937)

- ↑ Marcus Lee Hansen, The Mingling of the Canadian and American Peoples. Vol. 1: Historical (1940); David D. Harvey, Americans in Canada: Migration and Settlement since 1840 (1991)

- ↑ Renee Kasinsky, "Refugees from Militarism: Draft Age Americans in Canada (1976)

- ↑ Yves Roby, The Franco-Americans of New England (2004); Elliott Robert Barkan, "French Canadians" in Stephan Thernstrom, ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) pp 389–401

- ↑ Alan A. Brookes, "Canadians, British" in Stephan Thernstrom, ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) pp 191ff.

- ↑ Stephan Thernstrom, ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) p 392.

- ↑ Mason Wade, The French Canadians, 1760–1945 (1955) p. 74.

- ↑ Thomas B. Allen, Tories: Fighting for the King in America's First Civil War (2010) p xviii

- ↑ Patrick Bode, "Upper Canada, 1793: Simcoe and the Slaves," Beaver 1993 73(3): 17–19; Paul Robert Magocsi, ed. Enyclopedia of Canada's Peoples (1999) p 142–3

- ↑ Bradford Perkins, The First Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1795–1805 (1955)

- ↑ George A. Rawlyk (1994). The Canada Fire: Radical Evangelicalism in British North America, 1775-1812. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 122. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies (2010).

- ↑ Stagg 2012, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ George F. G. Stanley, 1983, pg. 32

- ↑ David Heidler,Jeanne T. Heidler, The War of 1812,pg4

- ↑ Tucker 2011, p. 236.

- ↑ Nugent, p. 73.

- ↑ Nugent, p. 75.

- ↑ Carlisle & Golson 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Pratt 1925, pp. 9–15; Hacker 1924, pp. 365–395.

- ↑ Mark Zuehlke, For Honour's Sake: The War of 1812 and the Brokering of an Uneasy Peace (2007) is a Canadian perspective.

- ↑ W.L. Morton, The Kingdom of Canada (1969) ch 12

- ↑ A.J. Langguth, Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence (2006) ch 24

- ↑ Dunning, Tom (2009). "The Canadian Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 as a Borderland War: A Retrospective". Ontario History 101 (2): 129–141.

- ↑ Orrin Edward Tiffany, The Relations of the United States to the Canadian Rebellion of 1837–1838 (1905). excerpt and text search

- ↑ Jay Sexton (2005). Debtor Diplomacy: Finance and American Foreign Relations in the Civil War Era, 1837-1873. Oxford University Press. p. 206. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Doris W. Dashew, "The Story of An Illusion: The Plan To Trade 'Alabama' Claims For Canada," Civil War History, December 1969, Vol. 15 Issue 4, pp 332-348

- ↑ Shi, David E. (1978). "Seward's Attempt to Annex British Columbia, 1865-1869". Pacific Historical Review 47 (2): 217–238. doi:10.2307/3637972. JSTOR 3637972.

- ↑ Yossi Shain (1999). Marketing the American Creed Abroad: Diasporas in the U.S. and Their Homelands. Cambridge U.P. p. 53. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Mark Kurlansky (1998). Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. Penguin. p. 117. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ John J. Bukowczyk et al. Permeable Border: The Great Lakes Region as Transnational Region, 1650-1990 (University of Pittsburgh Press. 2005)

- ↑ J. Castell Hopkins, The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs: 1902 (1903), p. 327.

- ↑ Munro, John A. (1965). "English-Canadianism and the Demand for Canadian Autonomy: Ontario's Response to the Alaska Boundary Decision, 1903". Ontario History 57 (4): 189–203.

- ↑ Spencer Tucker (2011). World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 142.

- ↑ Baker, W. M. (1970). "A Case Study of Anti-Americanism in English-Speaking Canada: The Election Campaign of 1911". Canadian Historical Review 51 (4): 426–449. doi:10.3138/chr-051-04-04.

- ↑ Clements, Kendrick A. (1973). "Manifest Destiny and Canadian Reciprocity in 1911". Pacific Historical Review 42 (1): 32–52. doi:10.2307/3637741. JSTOR 3637741.

- ↑ Lewis E. Ellis (1968). Reciprocity, 1911: a study in Canadian-American relations. Greenwood. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Richard N. Kottman, "Herbert Hoover and the Smoot-Hawley Tariff: Canada, A Case Study," Journal of American History, Vol. 62, No. 3 (December 1975), pp. 609-635 in JSTOR

- ↑ McDonald, Judith; et al. "Trade Wars: Canada's Reaction to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff", (1997)". Journal of Economic History 57 (4): 802–826. doi:10.2307/2951161.

- ↑ Carlson, Peter (December 30, 2005). "Raiding the Icebox". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Bell, Christopher M. (1997). "Thinking the Unthinkable: British and American Naval Strategies for an Anglo-American War, 1918–1931". International History Review 19 (4): 789–808. doi:10.1080/07075332.1997.9640804.

- ↑ Arnold A. Offner, American Appeasement: United States Foreign Policy and Germany, 1933-1938 (1969) p. 256

- ↑ Galen Roger Perras, Franklin Roosevelt and the Origins of the Canadian-American Security Alliance, 1933-1945 (1998)

- ↑ Richard Jensen, "Nationalism and Civic Duty in Wartime: Comparing World Wars in Canada and America," Canadian Issues / Thèmes Canadiens, December 2004, pp 6–10

- ↑ Rachel Lea Heide, "Allies in Complicity: The United States, Canada, and the Clayton Knight Committee's Clandestine Recruiting of Americans for the Royal Canadian Air Force, 1940-1942," Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2004, Vol. 15, pp 207–230

- ↑ Galen Roger Perras, "Who Will Defend British Columbia? Unity of Command on the West Coast, 1934-1942," Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Spring 1997, Vol. 88 Issue 2, pp 59–69

- ↑ McNeil Earle, Karl (1998). "Cousins of a Kind: The Newfoundland and Labrador Relationship with the United States". American Review of Canadian Studies 28 (4): 387–411. doi:10.1080/02722019809481611.

- ↑ Bruce Muirhead, "From Special Relationship to Third Option: Canada, the U.S., and the Nixon Shock," American Review of Canadian Studies, Vol. 34, 2004 online edition

- ↑ Hills, Carla A. "NAFTA's Economic Upsides: The View from the United States." Foreign Affairs 93 (2014): 122. online

- ↑ Wilson, Michael. "NAFTA's Unfinished Business: The View from Canada." Foreign Affairs 93 (2014): 128. online

- ↑ David Stephen Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Encyclopedia of the War of 1812 (2004) p. 194

- ↑ J. L. Granatstein, Yankee Go Home: Canadians and Anti-Americanism (1997)

- ↑ Damien-Claude Bélanger, Prejudice and Pride: Canadian Intellectuals Confront the United States, 1891–1945 (University of Toronto Press, 2011), pp 16, 180

- ↑ Richard Collins, Culture, Communication, and National Identity: The Case of Canadian Television (U. of Toronto Press, 1990) p. 25

- ↑ David Meren, "'Plus que jamais nécessaires': Cultural Relations, Nationalism and the State in the Canada-Quebec-France Triangle, 1945–1960," Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 2009, Vol. 19 Issue 1, pp 279–305,

- 1 2 Paula Ruth Gilbert, Violence and the Female Imagination: Quebec's Women Writers (2006) p. 114

- ↑ Barbara S. Groseclose; Jochen Wierich (2009). Internationalizing the History of American Art: Views. Penn State Press. p. 105. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Jamie Glazov (2002). Canadian Policy Toward Khrushchev's Soviet Union. McGill-Queens. p. 138. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ J. M. Bumsted in Paul Magocsi, ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 197. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ John R. Wennersten (2008). Leaving America: The New Expatriate Generation. Greenwood. p. 44. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Brendon O'Connor (2007). Anti-Americanism: Comparative perspectives. Greenwood. p. 60. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Seymour Martin Lipset (1990). Continental Divide: The Values and Institutions of the United States and Canada. Routledge. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Camille R. La Bossière (1994). Context North America: Canadian/U.S. Literary Relations. U. of Ottawa Press. p. 11. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Daniel Drache (2008). Big Picture Realities: Canada and Mexico at the Crossroads. Wilfrid Laurier U.P. p. 115. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ "Prime ministers and presidents". CBC News. February 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Obama to visit Canada Feb. 19, PMO confirms - CTV News". Ctv.ca. January 28, 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ↑ Obama loses boozy bet with Harper - The Globe and Mail

- ↑ Barack Obama follows through on Olympic beer bet

- ↑ "Joint Statement by President Obama and Prime Minister Harper of Canada on Regulatory Cooperation". Whitehouse.gov. February 4, 2011. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ↑ "PM and U.S. President Obama announce shared vision for perimeter security and economic competitiveness between Canada and the United States". Office of the Prime Minister of Canada. February 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-19-18. Retrieved February 26, 2011. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - ↑ "United States-Canada Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC) Joint Action Plan: Developing and implementing the Joint Action Plan". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Prime Minister of Canada. December 7, 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-19-17. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - ↑ "Notice: Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC) Over-the-Counter (OTC) Products: Common Monograph Working Group: Selection of a Monograph for Alignment". Canada's Action Plan. Government of Canada. January 10, 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-11-08. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Canada-U.S. border agreement a good thing". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Jordan, Roger (November 20, 2015). "Trudeau promises Obama an enhanced Canada-US partnership". World Socialist Web Site (International Committee of the Fourth International). Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ Harris, Kathleen (November 6, 2015). "Justin Trudeau 'disappointed' with U.S. rejection of Keystone XL". CBC News (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ Hall, Chris (November 20, 2015). "Trudeau warmly embraced by Obama, but don't expect concessions from U.S.". CBC News (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ Cullen, Catherine (November 17, 2015). "Justin Trudeau says Canada to increase number of training troops in Iraq". CBC News (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Barack Obama and Justin Trudeau set a date for first meeting in Washington". Toronto Star. The Canadian Press. December 28, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ Background note on Canada, U.S. State Department

- ↑ Patrick Lennox (2009). At Home and Abroad: The Canada-US Relationship and Canada's Place in the World. UBC Press. p. 107. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Canadian Peace Research Institute (2006). Peace Research. Canadian Peace Research and Education Association. Retrieved 2015-11-06. vol 38 page 8

- ↑ Webcast Panel Discussion "Ties That Bind" at the Pritzker Military Library on August 17, 2012

- ↑ "U.S. 'friendly fire' pilot won't face court martial". CBC News. July 6, 2004. Retrieved January 28, 2004.

- ↑ "Pilots blamed for 'friendly fire' deaths". BBC News. August 22, 2002. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- ↑ Wayne S. Cox; Bruno Charbonneau (2010). Locating Global Order: American Power and Canadian Security After 9/11. UBC Press. p. 119. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Harper, Tim (March 22, 2003). "Canadians back Chrétien on war, poll finds". Toronto Star. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Spector, Norman (November 20, 2006). "Clinton speaks on Afghanistan, and Canada listens" Check

|url= - ↑ Eric Miller (2002). The Outlier Sectors: Areas of Non-free Trade in the North American Free Trade Agreement. BID-INTAL. p. 19. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ The Embassy of the U.S.A., Ottawa - United States - Canada Relations

- ↑ Clean Air Markets | US EPA

- ↑ Canada- United States Air Quality Agreement - Air - Environment Canada

- ↑ Exclusive Interview: Brian Mulroney remembers his friend Ronald Reagan | National Post

- ↑ Freed, Kenneth; Gerstenzang, James (April 6, 1987). "Mulroney Asks Reagan for Treaty on Acid Rain". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Edward S. Cassedy; Peter Z. Grossman (1998). Introduction to Energy: Resources, Technology, and Society. Cambridge U.P. p. 157. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ CEC - About us: About the CEC

- ↑ Canada’s environment policy to follow the U.S.: Minister

- ↑ Resources | Climate Prosperity

- ↑ Michael Rheta Martin (1978). Dictionary of American History: With the Complete Text of the Constitution of the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 227. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Murphy, Orville T. (1965). "The Comte De Vergennes, The Newfoundland Fisheries And The Peace Negotiation Of 1783: A Reconsideration". Canadian Historical Review 46 (1): 32–46. doi:10.3138/chr-046-01-02.

- ↑ Golladay, V. Dennis (1973). "The United States and British North American Fisheries, 1815-1818". American Neptune 33 (4): 246–257.

- ↑ Alvin, C. Gluek Jr (1976). "Programmed Diplomacy: The Settlement of the North Atlantic Fisheries Question, 1907-12". Acadiensis 6 (1): 43–70.

- ↑ Kurkpatrick Dorsey (2009). The Dawn of Conservation Diplomacy: U.S.-Canadian wildlife protection treaties in the progressive era. University of Washington Press. p. 19ff. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ "U.S. warns Canada against easing pot laws". Cbc.ca. May 2, 2003. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ↑ http://wayback.archive.org/web/20130731191132/http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/prg/le/oc/_fl/us-canadian-report-drugs-eng.pdf

- ↑ Histor!ca "Election of 1891: A Question of Loyalty", James Marsh.

- ↑ Donald Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Old Chieftain (1955) p. 497

- ↑ Council on Foreign Relations, Documents on American foreign relations (1957) Volume 9 p 558

- ↑ John F. Kennedy. Address Before the Canadian Parliament in Ottawa. The American Presidency Project.

- ↑ "The Embassy of the U.S.A., Ottawa - United States - Canada Relations". Canada.usembassy.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-03-23. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ↑ From a speech by Trudeau to the National Press Club in Washington, DC, on March 25, 1969

- ↑ J. L. Granatstein and Robert Bothwell, Pirouette: Pierre Trudeau and Canadian Foreign Policy(1991) p 51

- ↑ J. L. Granatstein and Robert Bothwell, Pirouette: Pierre Trudeau and Canadian Foreign Policy(1991) p 195

- ↑ J. L. Granatstein and Robert Bothwell, Pirouette: Pierre Trudeau and Canadian Foreign Policy(1991) p 71

- ↑ The Rhetoric of 9/11: President George W. Bush - Address to Joint Session of Congress and the American People (9-20-01)

- ↑ "Statement by Prime Minister Stephen Harper". Office of the Prime Minister of Canada. January 20, 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-01-13. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Obama declares love for Canada, banishes Bush era". Reuters. February 19, 2009.

- ↑ Matthew Carnaghan, Allison Goody, "Canadian Arctic Sovereignty" (Library of Parliament: Political and Social Affairs Division, January 26, 2006); 2006 news

- ↑ "Cellucci: Canada should control Northwest Passage". CTV.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-02-22. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Canadian Government offices in the U.S". Canadainternational.gc.ca. April 5, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ↑ "American Government offices in Canada". Canada.usembassy.gov. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

Further reading

- Anderson, Greg; Christopher Sands (2011). Forgotten Partnership Redux: Canada-U.S. Relations in the 21st Century. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-60497-762-2. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- Azzi, Stephen. Reconcilable Differences: A History of Canada-US Relations (Oxford University Press, 2014)

- Behiels, Michael D. and Reginald C. Stuart, eds. Transnationalism: Canada-United States History into the Twenty-First Century (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2010) 312 pp. online 2012 review

- Bothwell, Robert. Your Country, My Country: A Unified History of the United States and Canada (2015), 400 pages; traces relations, shared values, and differences across the centuries

- Doran, Charles F., and James Patrick Sewell, "Anti-Americanism in Canada," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 497, Anti-Americanism: Origins and Context (May 1988), pp. 105–119 in JSTOR

- Clarkson, Stephen. Uncle Sam and Us: Globalization, Neoconservatism and the Canadian State (University of Toronto Press, 2002)

- Engler, Yves"The Black Book of Canadian Foreign Policy". Co-published: RED Publishing, Fernwood Publishing. April 2009. ISBN 978-1-55266-314-1.

- Ek, Carl, and Ian F. Fergusson. Canada-U.S. Relations (Congressional Research Service, 2010) 2010 Report, by an agency of the U.S. Congress

- Granatstein, J. L. Yankee Go Home: Canadians and Anti-Americanism (1997)

- Granatstein, J. L. and Norman Hillmer, For Better or for Worse: Canada and the United States to the 1990s (1991)

- Gravelle, Timothy B. "Partisanship, Border Proximity, and Canadian Attitudes toward North American Integration." International Journal of Public Opinion Research (2014) 26#4 pp: 453-474.

- Gravelle, Timothy B. "Love Thy Neighbo (u) r? Political Attitudes, Proximity and the Mutual Perceptions of the Canadian and American Publics." Canadian Journal of Political Science (2014) 47#1 pp: 135-157.

- Hale, Geoffrey. So Near Yet So Far: The Public and Hidden Worlds of Canada-US Relations (University of British Columbia Press, 2012); 352 pages focus on 2001-2011

- Holland, Kenneth. "The Canada–United States defence relationship: a partnership for the twenty-first century." Canadian Foreign Policy Journal ahead-of-print (2015): 1-6. online

- Holmes, Ken. "The Canadian Cognitive Bias and its Influence on Canada/US Relations." International Social Science Review (2015) 90#1 online.

- Holmes, John W. "Impact of Domestic Political Factors on Canadian-American Relations: Canada," International Organization, Vol. 28, No. 4, Canada and the United States: Transnational and Transgovernmental Relations (Autumn, 1974), pp. 611–635 in JSTOR

- Innes, Hugh, ed. Americanization: Issues for the Seventies (McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1972). ISBN 0-07-092943-2; re 1970s

- Lennox, Patrick. At Home and Abroad: The Canada-U.S. Relationship and Canada's Place in the World (University of British Columbia Press; 2010) 192 pages; the post–World War II period.

- Little, John Michael. "Canada Discovered: Continentalist Perceptions of the Roosevelt Administration, 1939-1945," PhD dissertation. Dissertation Abstracts International, 1978, Vol. 38 Issue 9, p5696-5697

- Lumsden, Ian, ed. The Americanization of Canada, ed. ... for the University League for Social Reform (University of Toronto Press, 1970). ISBN 0-8020-6111-7 pbk.

- Graeme S. Mount and Edelgard Mahant, An Introduction to Canadian-American Relations (1984, updated 1989)

- Molloy, Patricia. Canada/US and Other Unfriendly Relations: Before and After 9/11 (Palgrave Macmillan; 2012) 192 pages; essays on various "myths"