Campfire

A campfire is a fire at a campsite that provides light and warmth, and heat for cooking. It can also serve as a beacon, and an insect and predator deterrent. Established campgrounds often provide a stone or steel fire ring for safety. Campfires are a popular feature of camping.

History

First Campfire

A new analysis of burned antelope bones from caves in Swartkrans, South Africa, confirms that Australopithecus robustus and Homo erectus built campfires roughly 1.6 million years ago.[1] Nearby evidence within Wonderwerk Cave, at the edge of the Kalahari Desert, has been called the oldest known controlled fire.[2] Microscopic analysis of plant ash and charred bone fragments suggests that materials in the cave were not heated above about 1,300 °F (704 °C). This is consistent with preliminary findings that the fires burned grasses, brush, and leaves. Such fuel would not produce hotter flames. The data suggests humans were cooking prey by campfire as far back as the first appearance of Homo erectus. 1.9 million years ago.[3]

Safety

Finding a site

Ideally, campfires should be made in a fire ring. If a fire ring is not available, a temporary fire site may be constructed. Bare rock or unvegetated ground is ideal for a fire site. Alternatively, turf may be cut away to form a bare area and carefully replaced after the fire has cooled to minimize damage. Another way is to cover the ground with sand, or other soil mostly free of flammable organic material, to a depth of a few inches. A ring of rocks is sometimes constructed around a fire. Fire rings, however, do not fully protect material on the ground from catching fire. Flying embers are still a threat, and the fire ring may become hot enough to ignite material in contact with it.

Safety measures

- Avoid building campfires under hanging branches or over steep slopes, and clear a ten-foot diameter circle around the fire of all flammable debris.[4]

- Have lots of water nearby and a shovel to smother an out-of-control fire with dirt.[4]

- Minimize the size of the fire to prevent problems from occurring.[4]

- Never leave a campfire unattended.[4]

- When extinguishing a campfire, use plenty of water, then stir the mixture and add more water. Afterward, check that there are no burning embers left whatsoever.[4] If water is unavailable, use dirt.[4] Take a green leaf and place it on your coals, if the leaf curls up the coals are still too hot.

- Never bury hot coals, they can continue to burn and cause root fires or wildfires.[4] Be aware of roots if digging a hole for your fire.

- Make sure the fire pit is large enough for the campfire and there are no combustibles near the campfire. Also avoid building the campfire on a windy day. [5]

Types of fuel

There are, by conventional classification, three types of material involved in building a fire without manufactured fuels.

- Tinder lights easily and is used to start an enduring campfire. It is anything that can be lit with a match and is usually classified as being thinner than your little finger. A few decent natural tinders are birch bark, cedar bark, and fatwood, where available; followed by dead, dry pine needles or grass; a more comprehensive list is given in the article on tinder. Though not natural, steel wool makes excellent tinder and can be started with steel and flint, or a 9 volt battery without difficulty.

- Kindling is an arbitrary classification including anything bigger than tinder but smaller than fuel wood. In fact, there are gradations of kindling, from sticks thinner than a finger to those as thick as a wrist. A quantity of kindling sufficient to fill a hat may be enough, but more is better.

- Fuel can be different types of timber. Timber ranges from small logs two or three inches (76 mm) across to larger logs that can burn for hours. It is typically difficult to gather without a hatchet or other cutting tool. In heavily used campsites, fuel wood can be hard to find, so it may have to be brought from home or purchased at a nearby store.

In the United States, areas that allow camping, like State Parks and National Parks, often let campers collect firewood lying on the ground. Some parks don't do this for various reasons, e.g. if they have erosion problems from campgrounds near dunes). Parks almost always forbid cutting living trees, and may also prohibit collecting dead parts of standing trees.

In most realistic cases nowadays, non-natural additions to the fuels mentioned above will be used. Often, charcoal lighters like hexamine fuel tablets or ethyl alcohol will be used to start the fire, as well as various types of scrap paper. With the proliferation of packaged food, it is quite likely that plastics will be incinerated as well, a practice that not only produces toxic fumes but will also leave polluted ashes behind because of incomplete combustion at too-low open fire temperatures.

Construction styles

There are a variety of designs to choose from in building a campfire. A functional design is very important in the early stages of a fire. Most of them make no mention of fuel wood—in most designs, fuel wood is never placed on a fire until the kindling is burning strongly.

- The tipi fire-build takes some patience to construct. First, the tinder is piled up in a compact heap. The smaller kindling is arranged around it, like the poles of a tipi. For added strength, it may be possible to lash some of the sticks together. A tripod lashing is quite difficult to execute with small sticks, so a clove hitch should suffice. (Synthetic rope should be avoided, since it produces pollutants when it burns.) Then the larger kindling is arranged above the smaller kindling, taking care not to collapse the tipi. A separate tipi as a shell around the first one may work better. Tipi fires are excellent for producing heat to keep people warm. The gases from the bottom quickly come to the top as you add more sticks.[6] However, one downside to a Tipi fire is that when it burns, the logs become unstable and can fall over. This is especially concerning with a large fire.

- A lean-to fire-build starts with the same pile of tinder as the tipi fire-build. Then, a long, thick piece of kindling is driven into the ground at an angle, so that it overhangs the tinder pile. The smaller pieces of kindling are leaned against the big stick so that the tinder is enclosed between them.

- In an alternative method, a large piece of fuel wood or log can be placed on the ground next to the tinder pile. Then kindling is placed with one end propped up by the larger piece of fuel wood, and the other resting on the ground, so that the kindling is leaning over the tinder pile. This method is useful in very high winds, as the piece of fuel wood acts as a windbreak.

- A log cabin fire-build likewise begins with a tinder pile. The kindling is then stacked around it, as in the construction of a log cabin. The first two kindling sticks are laid parallel to each other, on opposite sides of the tinder pile. The second pair is laid on top of the first, at right angles to it, and also on opposite sides of the tinder. More kindling is added in the same manner. The smallest kindling is placed over the top of the assembly. Of all the fire-builds, the log cabin is the least vulnerable to premature collapse, but it is also inefficient, because it makes the worst use of convection to ignite progressively larger pieces of fuel. However, these qualities make the log cabin an ideal cooking fire as it burns for a long period of time and can support cookware.

- A variation on the log cabin starts with two pieces of fuel wood with a pile of tinder between them, and small kindling laid over the tops of the logs, above the tinder. The tinder is lit, and the kindling is allowed to catch fire. When it is burning briskly, it is broken and pushed down into the consumed tinder, and the larger kindling is placed over the top of the logs. When that is burning well, it is also pushed down. Eventually, a pile of kindling burns between two pieces of fuel wood, and soon the logs catch fire from it.

- Another variation is called the funeral pyre method because it is used for building funeral pyres. Its main difference from the standard log cabin is that it starts with thin pieces and moves up to thick pieces. If built on a large scale, this type of fire-build collapses in a controlled manner without restricting the air flow.

- A cross-fire is built by positioning two pieces of wood with the tinder in between. Once the fire is burning well, additional pieces of wood are placed on top in layers that alternate directions. This type of fire creates coals suitable for cooking.

- A hybrid fire combines the elements of both the tipi and the log cabin creating an easily lit yet stable fire structure. The hybrid is made by first erecting a small tipi and then proceeding to construct a log cabin around it. This fire structure combines benefits of both fire types: the tipi allows the fire to ignite easily and the log cabin sustains the fire for a long time.

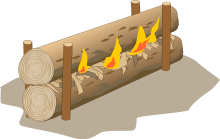

- The traditional Finnish rakovalkea (literally "slit bonfire") is constructed by placing one long piece of fuel wood atop another, parallel, and bolstering them in place with four sturdy posts driven into the ground. (Traditionally, whole un-split tree trunks provide the fuel wood.) Kindling and tinder are placed between the logs in sufficient quantity (while avoiding the very ends) to raise the upper log and allow ventilation. The tinder is always lit at the center so the bolstering posts do not burn prematurely. The rakovalkea has two excellent features. First, it burns slowly but steadily when lit; it does not require arduous maintenance, but burns for a very long time. A well constructed rakovalkea of two thick logs of two meters in length can warm two lean-to shelters for a whole sleeping shift. The construction causes the logs themselves to protect the fire from the wind. Thus, exposure to smoke is unlikely for the sleepers; nevertheless someone should always watch in case of an emergency. Second, it can be easily scaled to larger sizes (for a feast) limited only by the length of available tree trunks.

- Schwedenfackel, or Schwedenfeuer (Schwedenfeuer, German Wikipedia). Roughly translated, it means "Swedish fire torch", also known by other names, including Swedish (log) candle, and Swedish log stove. It is unique because it uses only one piece of fairly decent sized fuel wood as its fuel. The log is either cut (usually only partially, but other variants do include totally splitting) and then set upright (ideally, the log needs to be cut evenly and on a level surface for stability). Tinder and kindling are added to the preformed chamber, from the initial cuts. Eventually, the fire is self-feeding. The flat, circular top provides a surface to place a kettle, or pan for cooking, boiling liquids, etc. The elevated position of the fire can serve as a better beacon than the typical ground based campfire in some instances.[7][8]

- A keyhole fire is made in a keyhole-shaped fire ring, and is used in cooking. The large round area is used to build a fire to create coals. As coals develop, they are scraped into the rectangular area used for cooking.

- A "top lighter" fire is built similar to a log cabin or pyre, but instead of the tinder and kindling being placed inside the cabin, it is placed in a tipi on top. The small tipi is lighted on top, and the coals eventually fall down into the log cabin. Outdoor youth organizations often build these fires for "council fires" or ceremonial fires. They burn predictably, and with some practice a builder can estimate how long they will last. They also do not throw off much heat, which isn't needed for a ceremonial fire. The fire burns from the top down, with the layer of hot coals and burning stubs igniting the next layer down.

- Another variation to the top lighter, log cabin, or pyre is known by several names, most notably the pyramid, self-feeding, and upside-down [method]. The reasoning for this method are twofold. First, the layers of fuel wood take in the heat from the initial tinder/kindling therefore it is not lost to the surrounding ground. In effect, the fire is "off the ground", and burns its way down through its course. And secondly, this fire type requires minimal labor, thereby making it ideal as a fire of choice before bedding down for the evening without having to get up periodically to add fuel wood and/or stoke the fire to keep it going. Start by adding the largest fuel wood in a parallel "layer", then continue to add increasingly smaller and smaller fuel wood layers perpendicularly to the last layer. Once enough wood is piled, there should be a decent "platform" to make the tipi [tinder/kindling] to initiate the fire.

- A Star Fire, or Indian Fire, is the fire design often depicted as the campfire of the old West. Someone lays six or so logs out like the spokes of a wheel (star shaped). They start the fire at the "hub," and push each log towards the center as the flames consume the ends. Method:

- Build a small ditch, about five inches across and about an inch deep.

- Set up five to seven pieces of wood about the size of a forearms in a star around the ditch, with a bit of the end sticking in over the edge.

- Line the inside of the ditch and a few inches inside the pieces of fuel wood with kindling. Have more kindling set aside for later use.

- Set up a tinder nest on top of the kindling in the ditch.

- Surround the tinder with more kindling—the more the better, but not enough to restrict air flow, and leaving access to light the tinder.

Light the tinder with a match or other source

- Blow gently yet firmly until the fire lights. Add kindling as needed until the ends of the fuel ignites.

As the fuel slowly burns, push in the logs by the ends to keep the fire burning. When the fuel runs short, add more fuel wood. This fire is ideal for calm conditions and can be kept burning all night with little maintenance. The fire can be controlled easily, and is a great cooking fire because it is so predictable.

Lighting the fire

Once the fire is built, the next step is to light the tinder, using either an ignition device such as a match or a lighter. A reasonably skillful fire-builder using reasonably good material only needs one match. The tinder burns brightly, but be reduced to glowing embers within half a minute. If the kindling does not catch fire, the fire-builder must gather more tinder, determine what went wrong and try to fix it.

One of five problems can prevent a fire from lighting properly: wet wood, wet weather, too little tinder, too much wind, or a lack of oxygen. Rain will douse a fire, but a combination of wind and fog also has a stifling effect. Metal fire rings generally do a good job of keeping out wind, but some of them are so high as to impede the circulation of oxygen in a small fire. To make matters worse, these tall fire rings also make it very difficult to blow on the fire properly.

A small, enclosed fire that has slowed down may require vigorous blowing to get it going again, but excess blowing can extinguish a fire. Most large fires easily create their own circulation, even in unfavorable conditions, but the variant log-cabin fire-build suffers from a chronic lack of air so long as the initial structure is maintained.

Once large kindling is burning, all kindling should be put on the fire, save for one piece at least a foot long. This piece is useful later to push pieces of fuel wood where needed. Once all of the kindling is burning, the fuel wood should be placed on top of it (unless, as in the rakovalkea fire-build, it is already there). For best results, two or more pieces of fuel wood should be leaned against each other, as in the tipi fire-build.

Activities

Campfires have been used for cooking since time immemorial. Possibly the simplest method of cooking over a campfire and one of the most common is to roast food on long skewers that can be held above the flames. This is a popular technique for cooking hot dogs or toasting marshmallows for making s'mores. This type of cooking over the fire typically consists of comfort foods that are easy to prepare. There is also no clean up involved unlike an actual kitchen. [9]Another technique is to use pie irons—small iron molds with long handles. Campers put slices of bread with some kind of filling into the molds and put them over hot coals to cook. Campers sometimes use elaborate grills, cast iron pots, and fire irons to cook. Often, however, they use portable stoves for cooking instead of campfires. :For more information, see Campfire cooking.

Other practical, though not commonly needed, applications for campfires include drying wet clothing, alleviating hypothermia, and distress signaling. Most campfires, though, are exclusively for recreation, often as a venue for conversation, storytelling, or song. Another traditional campfire activity involves impaling marshmallows on sticks or uncoiled wire coat hangers, and roasting them over the fire. Roasted marshmallows may also be used for s'mores.

Dangers

Beside the danger of people receiving burns from the fire or embers, campfires may spread into a larger fire. A campfire may burn out of control in two basic ways: on the ground or in the trees. Dead leaves or pine needles on the ground may ignite from direct contact with burning wood, or from thermal radiation. If a root, particularly a dead one, is exposed to fire, it may smoulder underground and ignite the parent tree long after the original fire is doused and the campers have left the area. Alternatively, airborne embers (or their smaller kin, sparks) may ignite dead material in overhanging branches. This latter threat is less likely, but a fire in a branch is extremely difficult to put out without firefighting equipment, and may spread more quickly than a ground fire.

Embers may simply fall off logs and float away in the air, or exploding pockets of sap may eject them at high speed. With these dangers in mind, some places prohibit all open fires, particularly at times prone to wildfires.

Many public camping areas prohibit campfires. Public areas with large tracts of woodland usually have signs that indicate the fire danger level, which usually depends on recent rain and the amount of deadfall or dry debris. Even in safer times, it is common to require registration and permits to build a campfire. Such areas are often kept under observation by rangers, who will dispatch someone to investigate any unidentified plume of smoke.

Extinguishing the fire

Leaving a fire unattended can be dangerous. Any number of accidents might occur in the absence of people, leading to property damage, personal injury or possibly a wildfire. Ash is a good insulator, so embers left overnight only lose a fraction of their heat. It is often possible to restart the new day's fire using the embers.

To properly cool a fire, splash water on all embers, including places that are not glowing red. Splashing the water is both more effective and efficient in extinguishing the fire. The water boils violently and carries ash in the air with it, dirtying anything nearby but not posing a safety hazard. Pour the water until the hissing stops. Then stir the ashes with a stick to make sure that the water penetrates all the layers. If the hissing continues, add more water. When the fire is fully extinguished, the ashes are cool to the touch.

If water is scarce, use sand to deprive the fire of oxygen. Sand works well, but is less effective than water at absorbing heat. Once the fire is covered thoroughly with sand, pour any water that can be spared over the sand and stir it into the ash.

When winter or "ice" camping with an inch or more of snow on the ground, neither of the above protocols are necessary—simply douse visible flames before leaving.

Finally, in lightly used wilderness areas, it is best to replace anything that was moved while preparing the fire site, and scatter anything that was gathered, so that it looks as natural as possible. Make certain that anything that was in or near the fire is cool first.

See also

References

- ↑ http://discovermagazine.com/2005/jan/first-campfire

- ↑ http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/339600/title/From_the_ashes%2C_the_oldest_controlled_fire

- ↑ Charles Choi, LiveScience Contributor "History Of Fire Milestone, One Million Years Old, Discovered In Homo Erectus' Wonderwerk Cave" Posted: 04/ 2/2012 3:29 pm Updated: 04/ 2/2012 4:08 pm http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/04/02/history-fire-million-homo-erectus_n_1397810.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Campfire Safety." USDA Forest Service. Accessed August 2011.

- ↑ Schatz, John (2001). "Summer Outdoor Safety". Mobility Forum 10 (2): 23.

- ↑ "The Good Kind of Hot Spot". Backpacker 42 (8): 74.

- ↑ Bauanweisung (German) (PDF; 101 kB)

- ↑ (German)

- ↑ Rittman, Allison (2012). "Campfire-Inspired Cooking". Prepared Foods 181 (1): 79-84.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Campfire. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Transwiki:Campfire |

| Wikivoyage has travel information for Campfire. |

![]() The dictionary definition of campfire at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of campfire at Wiktionary

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||