Ivory-billed woodpecker

| Ivory-billed woodpecker | |

|---|---|

| |

| A hand-coloured photo of a male from 1935 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

| Genus: | Campephilus |

| Species: | C. principalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Campephilus principalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Campephilus p. principalis | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Picus principalis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) is one of the largest woodpeckers in the world, at roughly 20 inches (51 cm) in length and 30 inches (76 cm) in wingspan. It is native to the virgin forests of the southeastern United States (along with a separate subspecies native to Cuba). Due to habitat destruction, and to a lesser extent hunting, its numbers have dwindled to the point where it is uncertain whether any remain, though there have been reports that it has been seen again. Almost no forests today can maintain an ivory-billed woodpecker population.

The species is listed as critically endangered and possibly extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[1] The American Birding Association (ABA) lists the ivory-billed woodpecker as a Class 6 species, a category the ABA defines as "definitely or probably extinct."[2]

Reports of at least one male ivory-billed woodpecker in Arkansas in 2004 were investigated and subsequently published in April 2005 by a team led by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.[3] No definitive confirmation of those reports emerged, despite intensive searching over five years following the initial sightings.

An anonymous $10,000 reward was offered in June 2006 for information leading to the discovery of an ivory-billed woodpecker nest, roost or feeding site.[4] In December 2008, the Nature Conservancy announced a reward of $50,000 to the person who can lead a project biologist to a living ivory-billed woodpecker.

In late September 2006, a team of ornithologists from Auburn University and the University of Windsor published reports of their own sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers along the Choctawhatchee River in northwest Florida, beginning in 2005.[5] These reports were accompanied by evidence that the authors themselves considered suggestive for the existence of ivory-billed woodpeckers. Searches in this area of Florida through 2009 failed to produce definitive confirmation.

Despite these high-profile reports from Arkansas and Florida and sporadic reports elsewhere in the historic range of the species since the 1940s, there is no conclusive evidence for the continued existence of the ivory-billed woodpecker; i.e., there are no unambiguous photographs, videos, specimens or DNA samples from feathers or feces of the ivory-billed woodpecker. Land acquisition and habitat restoration efforts have been initiated in certain areas where there is a relatively high probability that the species may have survived to protect any possible surviving individuals.

Taxonomy

Ivory-billed woodpecker is the common name of several species of woodpecker distinguished by having a bill that resembles ivory:

- Campephilus, a genus of woodpecker sometimes called the Ivory-billed woodpecker, although the term is more commonly used to describe the American and Cuban ivory-billed woodpeckers.

- Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis bairdii or Campephilus bairdii), now believed to be extinct.

- American ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis principalis or Campephilus principalis), described here.

The Ivory-billed woodpecker is the type species for the genus Campephilus, a group of large American woodpeckers. Although the Ivory-billed looks very similar to the pileated woodpeckers they are not close relatives as the pileated is a member of the genus Dryocopus.

Ornithologists have traditionally recognized two subspecies of this bird: the American Ivory-billed, the more famous of the two, and the Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker. The two look similar despite differences in size and plumage. There is some controversy over whether the Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker is more appropriately recognized as a separate species. A recent study compared DNA samples taken from specimens of both ivory-billed birds along with the imperial woodpecker, a larger but otherwise very similar bird. It concluded not only that the Cuban and American Ivory-billed woodpeckers are genetically distinct, but also that they and the imperial form a North American clade within Campephilus that appeared in the Mid-Pleistocene.[6] The study does not attempt to define a lineage linking the three birds, though it does imply that the Cuban bird is more closely related to the imperial.[6]

The American Ornithologists' Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature has said it is not yet ready to list the American and Cuban as separate species. Lovette, a member of the committee, said that more testing is needed to support that change, but concluded that "These results will likely initiate an interesting debate on how we should classify these birds."[7] Before this study, it was thought that the Cuban Ivory-billed were descended from mainland woodpeckers, either introduced to Cuba by Native Americans or accidentals that flew to the island themselves.[8]

While recent evidence suggesting that American ivory-billed woodpeckers may still exist in the wild has caused excitement in the ornithology community, no similar evidence exists for the Cuban Ivory-billed bird, believed to be extinct since the last sighting in the late 1980s.

Description

The ivory-billed woodpecker ranks among the largest woodpeckers in the world and is the largest in the United States. The closely related and likewise possibly extinct imperial woodpecker (C. imperialis) of western Mexico is, or was, the largest woodpecker. The Ivory-billed has a total length of 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 in) and, based on very scant information, weighs about 450 to 570 g (0.99 to 1.26 lb). It has a typical 76 cm (30 in) wingspan. Standard measurements attained included a wing chord length of 23.5–26.5 cm (9.3–10.4 in), a tail length of 14–17 cm (5.5–6.7 in), a bill length of 5.8–7.3 cm (2.3–2.9 in) and a tarsus length of 4–4.6 cm (1.6–1.8 in).[9]

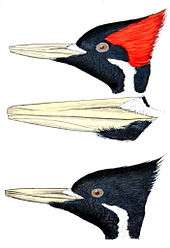

The bird is shiny blue-black with white markings on its neck and back and extensive white on the trailing edge of both the upper- and underwing. The underwing is also white along its forward edge, resulting in a black line running along the middle of the underwing, expanding to more extensive black at the wingtip. In adults, the bill is ivory in color, chalky white in juveniles. Ivory-bills have a prominent crest, although in juveniles it is ragged. The crest is black in juveniles and females. In males, the crest is black along its forward edge, changing abruptly to red on the side and rear. The chin of an ivory-bill is black. When perched with the wings folded, ivory-bills of both sexes present a large patch of white on the lower back, roughly triangular in shape. These characteristics distinguish it from the smaller and darker-billed pileated woodpecker. The pileated normally is brownish-black, smoky, or slaty black in color. It also has a white neck stripe but the back is normally black. Pileated juveniles and adults have a red crest and a white chin. Pileateds normally have no white on the trailing edges of their wings and when perched normally show only a small patch of white on each side of the body near the edge of the wing. However, pileated woodpeckers, apparently aberrant individuals, have been reported with white trailing edges on the wings, forming a white triangular patch on the lower back when perched. Like all woodpeckers, the ivory-bill has a strong and straight bill and a long, mobile, hard-tipped, barbed tongue. Among North American woodpeckers, the ivory-bill is unique in having a bill whose tip is quite flattened laterally, shaped much like a beveled wood chisel.

The bird's drum is a single or double rap. Four fairly distinct calls are reported in the literature and two were recorded in the 1930s. The most common, a kent or hant, sounds like a toy trumpet often repeated in series. When the bird is disturbed, the pitch of the kent note rises, it is repeated more frequently, and is often doubled. A conversational call, also recorded, is given between individuals at the nest, and has been described as kent-kent-kent. A recording of the bird, made by Arthur A. Allen, can be found here.

The ivory-billed woodpecker is sometimes referred to as the Grail Bird, the Lord God Bird, or the Good God Bird, all based on the exclamations of awed onlookers.[10] Other nicknames for the bird are King of the Woodpeckers and Elvis in Feathers.[11]

Habitat and diet

Ivory-billeds are known to prefer thick hardwood swamps and pine forests, with large amounts of dead and decaying trees. Prior to the American Civil War, much of the Southern United States was covered in vast tracts of primeval hardwood forests that were suitable as habitat for the bird. At that time, the ivory-billed woodpecker ranged from east Texas to North Carolina, and from southern Illinois to Florida and Cuba.[12] After the Civil War, the timber industry deforested millions of acres in the South, leaving only sparse isolated tracts of suitable habitat.

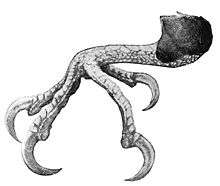

The ivory-billed woodpecker feeds mainly on the larvae of wood-boring beetles, but also eats seeds, fruit, and other insects. The bird uses its enormous white bill to hammer, wedge, and peel the bark off dead trees to find the insects. These birds need about 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi) per pair so they can find enough food to feed their young and themselves. Hence they occur at low densities even in healthy populations. The more common pileated woodpecker may compete for food with this species.

Breeding biology

The ivory-billed woodpecker is thought to pair for life. Pairs are also known to travel together. These paired birds will mate every year between January and May. Both parents work together to excavate a nest in a dead or partially dead tree about 8–15m from the ground before they have their young. Nest openings are typically ovular to rectangular in shape, and measure about 12–14 cm tall by 10 cm wide (4"-5 3/4" by 4")

Usually two to five eggs are laid and incubated for 3 to 5 weeks. Parents incubate the eggs cooperatively, with the male incubating from approximately 4:30 PM–6:30 AM while the female foraged, and vice versa from 6:30 AM–4:30 PM. They feed the chicks for months. Young learn to fly about seven to eight weeks after hatching. The parents will continue feeding them for another two months. The family will eventually split up in late fall or early winter.[13]

Ornithologists speculate that they may live as long as 30 years.[14]

Status

Heavy logging activity exacerbated by hunting by collectors devastated the population of ivory-billed woodpeckers in the late 19th century. It was generally considered extinct in the 1920s when a pair turned up in Florida, only to be shot for specimens.[15]

In 1932, a Louisiana state representative, Mason Spencer of Tallulah, disproved premature reports of the demise of the species when, armed with a gun and a hunting permit, he killed an ivory-billed woodpecker along the Tensas River and took the specimen to his state wildlife office in Baton Rouge.[16]

By 1938, an estimated twenty woodpeckers remained in the wild, some six to eight of which were in the old-growth forest called the Singer Tract, owned by the Singer Sewing Company in Madison Parish in northeastern Louisiana, where logging rights were held by the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. The company brushed aside pleas from four Southern governors and the National Audubon Society that the tract be publicly purchased and set aside as a reserve. By 1944, the last known ivory-billed woodpecker, a female, was gone from the cut-over tract.[17]

Reported sightings: 1940s to 1990s

The first audio and only video recording made of the ivory-billed woodpecker was created as part of a 1935 study by a group of Cornell scientists in the Singer Tract in Madison Parish, Louisiana.[18] The ivory-billed woodpecker was listed as an endangered species on 11 March 1967, though the only evidence of its existence at the time was a possible recording of its call made in East Texas. The last reported sighting of the Cuban subspecies (C. p. bairdii), after a long interval, was in 1987; it has not been seen since. The Cuban Exile journalist and author John O'Donnell-Rosales, who was born in the area of Cuba with the last confirmed sightings, reported sightings near the Alabama coastal delta in 1994, but these were never properly investigated by state wildlife officials.

Two tantalizing photos were given to Louisiana State University museum director George Lowery in 1971 by a source who wished to remain anonymous but who came forward in 2005 as outdoorsman Fielding Lewis.[19]

The photos, taken with a cheap Instamatic camera, show what appears to be a male Ivory-billed perched on the trunks of two trees in the Atchafalaya Basin of Louisiana. The bird's distinctive bill is not visible in either photo and the photos – taken from a distance – are very grainy. Lowery presented the photos at the 1971 annual meeting of the American Ornithologists Union. Skeptics dismissed the photos as frauds; seeing that the bird is in roughly the same position in both photos, they suggested they may have been of a mounted specimen.

There were numerous unconfirmed reports of the bird,[20] but many ornithologists believed the species had been wiped out completely, and it was assessed as "extinct" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources in 1994. This assessment was later altered to "critically endangered" on the grounds that the species could still be extant.[1]

2002 Pearl River expedition

In 1999, there was an unconfirmed sighting of a pair of birds in the Pearl River region of southeast Louisiana by a forestry student, David Kulivan, which some experts considered very compelling. In a 2002 expedition in the forests, swamps, and bayous of the Pearl River Wildlife Management Area by LSU, biologists spent 30 days searching for the bird.[21]

In the afternoon of 27 January 2002, after ten days, a rapping sound similar to the "double knock" made by the ivory-billed woodpecker was heard and recorded. The exact source of the sound was not found because of the swampy terrain, but signs of active woodpeckers were found (i.e., scaled bark and large tree cavities). The expedition was inconclusive, however, as it was determined that the recorded sounds were likely gunshot echoes rather than the distinctive double rap of the ivory-billed woodpecker.[22]

2004/2005 Arkansas reports

A group of seventeen authors headed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (CLO) reported the discovery of at least one ivory-billed woodpecker, a male, in the Big Woods area of Arkansas in 2004 and 2005, publishing the report in the journal Science on 28 April 2005.[3]

One of the authors, who was kayaking in the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge, Monroe County, Arkansas, on 11 February 2004, reported on a website the sighting of an unusually large red-crested woodpecker. This report led to more intensive searches in the area and in the White River National Wildlife Refuge, undertaken in secrecy for fear of a stampede of bird-watchers, by experienced observers over the next fourteen months. About fifteen sightings occurred during the period (seven of which were considered compelling enough to mention in the scientific article), possibly all of the same bird. One of these more reliable sightings was on 27 February 2004. Bobby Harrison of Huntsville, Alabama and Tim Gallagher of Ithaca, New York, both reported seeing an ivory-billed woodpecker at the same time. The secrecy of the search permitted The Nature Conservancy and Cornell University to quietly buy up Ivory-billed habitat to add to the 120,000 acres (490 km2) of the Big Woods protected by the Conservancy.

A large woodpecker was videotaped on 25 April 2004; its size, wing pattern at rest and in flight, and white plumage on its back between the wings were cited as evidence that the woodpecker sighted was an ivory-billed woodpecker. That same video included an earlier image of what was suggested to be such a bird perching on a Water Tupelo (Nyssa aquatica).

The report also notes that drumming consistent with that of ivory-billed woodpecker had been heard in the region. It describes the potential for a thinly distributed population in the area, though no birds have been located away from the primary site.

In the fall of 2006, researchers developed and installed an "autonomous observatory" using robotic video cameras with image processing software that detects and records high resolution video of birds in flight inside a high probability zone in the Cache River area. As of August 2007, hundreds of birds have been recorded, including pileated woodpeckers, but not the ivory-billed woodpecker.

Debate

_male.jpg)

In June 2005, ornithologists at Yale University, the University of Kansas, and Florida Gulf Coast University prepared a scientific paper skeptical of the initial reports of rediscovery.

We were very skeptical of the first published reports, and ... data were not sufficient to support this startling conclusion.[23]

The paper was not published. Questions about the evidence for ivory-billed woodpecker persisted. The CLO authors could not say with absolute certainty that the sounds recorded in Arkansas were made by Ivory-bills.[24] Some skeptics, including Richard Prum, believe the video could have been of a pileated woodpecker.[25]

An article by Dina Cappiello in the Houston Chronicle published 18 December 2005 presented Richard Prum's position as follows:

Prum, intrigued by some of the recordings taken in Arkansas' Big Woods, said the evidence thus far is refutable.

The American Birding Association largely stayed out of the debate. On page 13 of Winging It (November/December 2005), a brief reference was made:

The ABA Checklist Committee has not changed the status of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker from Code 6 (EXTINCT) to another level that would reflect a small surviving population. The Committee is waiting for unequivocal proof that the species still exists.

In a Perspectives in Ornithology commentary published in The Auk in January 2006,[26] ornithologist Jerome Jackson detailed his skepticism of the Ivory-bill evidence:

Prum, Robbins, Brett Benz, and I remain steadfast in our belief that the bird in the Luneau video is a normal Pileated Woodpecker. Others have independently come to the same conclusion, and publication of independent analyses may be forthcoming [...] For scientists to label sight reports and questionable photographs as 'proof' of such an extraordinary record is delving into 'faith-based' ornithology and doing a disservice to science."

Fitzpatrick and co-authors responded with a lengthy piece[27] in the same scientific journal, protesting Jackson's harsh language, dismissive tone, "factual errors," and "poorly substantiated opinions" about the original paper. One of the most rancorous debates in the history of ornithology had begun in earnest. The two sides each published additional responses that seemed, to many ornithological observers, to have departed markedly from accepted scientific decorum. Jackson accused the Fitzpatrick team of "untruths", and Fitzpatrick accused Jackson of obviating the normal peer-review system with an opinion piece "treated as a scientific contribution by the public media."

In March 2006, a team headed by David A. Sibley of Concord, MA published a response[28] in the journal Science, asserting that the videotape was most likely of a pileated woodpecker, with mistakes having been made in the interpretation of its posture. They conclude that it lacked certain features of an ivory-billed woodpecker, and had others consistent with the pileated; they asserted positively that the blurry video images belonged to pileated woodpecker. The CLO team responded in the same issue of Science, standing by their original findings,[29] stating:

_-_Ivory-billed_Woodpecker_-_specimen_-_video.webm.jpg)

Claims that the bird in the Luneau video is a normal pileated woodpecker are based on misrepresentations of a pileated's underwing pattern, interpretation of video artifacts as plumage pattern, and inaccurate models of takeoff and flight behavior. These claims are contradicted by experimental data and fail to explain evidence in the Luneau video of white dorsal plumage, distinctive flight behavior, and a perched woodpecker with white upper parts."[29]

Other workers made claims disputing the validity of the Luneau video, including a web site discussing the evidence by Colby College biologist Louis Bevier, who stated:[30]

In sum, no evidence confirms the alleged rediscovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker. Indeed, confidence in the claim has eroded with failure to verify its existence despite massive searches.

A 2007 paper concluded that the Luneau video was consistent with the pileated woodpecker:[31]

New video analysis of Pileated Woodpeckers in escape flights comparable to that of the putative Ivory-billed Woodpecker filmed in Arkansas shows that Pileated Woodpeckers can display a wingbeat frequency equivalent to that of the Arkansas bird during escape flight. The critical frames from the Arkansas video that were used to identify the bird as an Ivory-billed Woodpecker are shown to be equally, or more, compatible with the Pileated Woodpecker.…The identification of the bird filmed in Arkansas in April 2004 as an Ivory-billed Woodpecker is best regarded as unsafe. The similarities between the Arkansas bird and known Pileated Woodpeckers suggest that it was most likely a Pileated Woodpecker.

Doubt was also cast on some of the auditory evidence (ARU recordings of double-raps) for the presence of ivory-billed woodpeckers in Arkansas and Florida. One group of researchers stated:[32]

All ARU double raps suggesting the presence of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker should be reconsidered in light of the phenomenon of duck wingtip collisions, especially those recorded in the winter months, when duck flocks are common across flooded bottomlands of the southeastern United States.

Cornell search efforts 2005–09

.jpg)

Cornell-organized searches in Arkansas and elsewhere from 2005 to 2008 did not produce any new photographic evidence of the species. The press release summarizing the 2005–6 search season stated:[33]

There were teasing glimpses and tantalizing sounds, but the 2005–2006 search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Arkansas has concluded without the definitive visual documentation being sought. The search, led by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, with support from Audubon Arkansas, stretched from November through April when ivory-bill activity would be highest and a lack of leaf-cover permitted clear views through the dense forest.… “The search teams were very skilled, not only technically but in the execution of the search,” said Dr. John Fitzpatrick, director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “Even though we didn’t get additional definitive evidence of the ivory-bill in Arkansas, we’re not discouraged. The vastness of the forest combined with the highly mobile nature of the bird warrant additional searching.”

It is interesting to note that, despite his harsh criticism of the 2005 evidence, Jerome A. Jackson agrees with the value of additional searches.[26] In May 2006, it was announced that a large search effort led by the Cornell team had been suspended for the season with only a handful of unconfirmed, fleeting sightings to report. At that point, conservation officers allowed the public back into areas of the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge that had been restricted upon the initial reported sightings.[34] The 2006–07 search season had similar results to those of the previous year: [35]

The Lab and its partners concluded the 2006–07 field season in Arkansas at the end of April with no additional definitive evidence of ivory-bills to complement the data gathered in 2004 and 2005. But [Ronald] Rohrbaugh and others are convinced the research should continue, not only in Arkansas, but in other states that are part of the bird’s historic range. “We’ll return to Arkansas for at least another field season,” says Rohrbaugh. “Searches there and searches conducted by other agencies throughout the Southeast are still turning up reports of sounds that cannot be explained away. However, there’s no way to know for sure yet if reported double knocks and kent-like sounds were made by an ivory-bill or something else.”

Likewise, the 2007–08 search season did not deliver conclusive evidence of the bird:[36]

The search teams covered lots of ground and tried new survey techniques…. Searchers documented more possible sightings and possible ivory-bill double knocks heard, but the definitive photograph, like the bird itself, remained elusive.

Cornell University did not field a search team in Arkansas during 2008–2009, but focused on mangrove habitats in southwest Florida, with a later visit planned for South Carolina. According to a Cornell University press release from January 2009, the 2008–09 season will be the last Cornell-sponsored search, absent confirmation of the bird:[37]

There will be a distinctly different flavor to this season’s search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Seven members of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s mobile search team will plunge into some of the most forbidding wilderness in southwestern Florida. …The work begins in Florida in early January and continues through mid-March. …In mid-March the Cornell Lab of Ornithology team will join the South Carolina search along the Congaree, PeeDee, and Santee Rivers.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-funded Ivory-billed Woodpecker searches will continue through the 2008–09 search season,” says Laurie Fenwood, Ivory-billed Woodpecker Recovery Team Coordinator for the U.S, Fish and Wildlife Service.…If no birds are confirmed, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology will not send an organized team into the field next year. “We remain committed to our original goal of striving to locate breeding pairs,” says Cornell Lab of Ornithology director John Fitzpatrick. “We will continue to accept and investigate credible reports of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, and to promote protection and restoration of the old growth conditions upon which this magnificent species depended across the entire southeastern United States.”

The 2008–09 search effort in southwest Florida found no evidence of the bird:[38]

We have found no signs of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. No sightings, double knocks or calls, no replies to our many double-knock imitations. We have seen a few cavities of the appropriate size and shape for ivory-bills, but these can be old, or exceptionally large Pileated Woodpecker cavities, or mammal-enlarged Pileated Woodpecker cavities.… Given the results, it is unlikely a population of any meaningful size of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers exists in south Florida.

In October 2009, Cornell scientists announced that their search for the ivory-billed woodpecker in North America was being suspended.[39] As of February 2010, the Cornell researchers concluded there was no hope of saving the bird, if it still exists:[40]

But after five years of fruitless searching, hopes of saving the species have faded. "We don't believe a recoverable population of ivory-billed woodpeckers exists," says Ron Rohrbaugh, a conservation biologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who headed the original search team.

2005/2006 Florida reports

In September 2006, new claims that the ivory-billed woodpecker may not be extinct were released by a research group consisting of members from Auburn University in Alabama and the University of Windsor in Ontario. Dr. Geoffrey E. Hill of Auburn University and Dr. Daniel Mennill of the University of Windsor have revealed a collection of evidence that the birds may still exist in the cypress swamps of the Florida panhandle. Their evidence includes 14 sightings of the birds and 300 recordings of sounds that can be attributed to the ivory-billed woodpecker, but also includes tell-tale foraging signs and appropriately sized tree nest cavities (Hill et al., 2006). This evidence remains inconclusive as it excludes the photographic or DNA evidence that many experts cite as necessary before the presence of the species can be confirmed. While Dr. Hill and Dr. Mennill are themselves convinced of the bird's existence in Florida, they are quick to acknowledge that they have not yet conclusively proven the species' existence. The research team is currently undertaking a more complete survey of the Choctawhatchee River, in hopes of obtaining photographic evidence of the bird's existence.[41] In March 2007 the Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee voted unanimously not to accept the 2005–06 reports of the ivory-billed woodpecker on the Choctawhatchee River:[42]

RC 06-610. Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus principalis. 21 May 2005 – 26 April 2006. Choctawhatchee River, Washington/Bay/Walton cos. A population of unknown size has been reported by a team from Auburn University from the lower Choctawhatchee River. There have been a few sightings but no photographs, some interesting recordings of “kent” calls and of double rap drums, and photographs taken of cavities and bark scaling. These observations were made on the heels of the much-publicized “rediscovery” of the species in Arkansas (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005). The species had not been documented to occur since 1944. The video documentation of the bird(s) from Arkansas, however, has been debated by many, although the record was accepted by the Arkansas Bird Records Committee. Our Committee felt that given the controversy of the Arkansas evidence, the species is best considered still extinct. Therefore only evidence that undoubtedly showed a living bird would be considered sufficient to accept a report.

The last specimen taken in Florida was in 1925; there have been numerous sight reports of varying credibility since, and one record of a feather found in a nest cavity in 1968 that was identified as an Ivory-billed Woodpecker inner secondary by Alexander Wetmore.

VOTE: NOT ACCEPT (0–7)

The Auburn/University of Windsor team continued search efforts but planned to cease updates on their web site in August 2009:[43]

(12 June 2008) We completed our 2008 effort to get definitive evidence for ivorybills in the Choctawhatchee River Basin in early May…. Team members had no sightings of ivorybills and only two sound detections in 2008.… So where does all this leave us? Pretty much in the same position as in June 2006. We have a large body of evidence that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers persist along the Choctawhatchee River in the Florida panhandle, but we do not have definitive proof that they exist. Either the excitement of the ivorybill hunt causes competent birders to see and hear things that do not exist and leads competent sound analysts to misidentify hundreds of recorded sounds, or the few ivorybills in the Choctawhatchee River Basin are among the most elusive birds on the planet.

(9 February 2009) There has been little to report, and my students and I [Geoff Hill] have been enjoying the calm. We continue to work to get definitive documentation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the Choctawhatchee River Basin.… To my knowledge, there have been no sightings of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in the Choctawhatchee region since last spring. There were a few double knock detections in January, but not by my paid crew, Brian [Rolek], or me.

(2 August 2009) I haven’t posted many updates on this site in the past 9 months because there hasn’t not [sic] been much to report.… Since the winter of 2008, we have had few sightings or sound detections by anyone—none by Brian or me—and none that I would rate very highly.… In short, our experience over the past year indicates that ivorybills have moved out of the areas where we encountered them from 2005 to 2008.… There is no way to know whether the birds are in different areas in the Choctawhatchee Basin, different forests in the region, or dead.…I won’t post any more updates on this site.

Publicity and tourism

In economically struggling east Arkansas, the speculation of a possible return of the Ivory-bill has served as a great source of economic exploitation, with tourist spending up 30%, primarily in and around the city of Brinkley, Arkansas. A woodpecker "festival", a woodpecker hairstyle (a sort of mohawk with red, white, and black dye), and an "Ivory-bill Burger" (made with 100% beef) have been featured locally. The lack of confirmed proof of the bird's existence, and the extremely small chance of actually seeing the bird even if it does exist (especially since the exact locations of the reported sightings are still guarded), have prevented the explosion in tourism some locals had anticipated.

Ivorybills have also been featured in "Skink, No Surrender" by Carl Hiaasen as a clue to where the protagonist's cousin can be found, for Ivorybills could only be found in one place in the world. Since the cousin was kidnapped and could not tell the people who were trying to find her where she was, she gave an implicit hint that she saw an Ivorybill, telling her finders, where she was.

Brinkley hosted "The Call of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Celebration" in February 2006. The celebration included exhibits, birding tours, educational presentations, a vendor market, and more.

Interviews with residents of Brinkley, Arkansas, heard on National Public Radio following the reported rediscovery were shared with musician Sufjan Stevens, who used the material to write a song titled "The Lord God Bird".[44][45]

Arkansas has made license plates featuring a graphic of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

References

- 1 2 3 BirdLife International (2013). "Campephilus principalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the ABA Checklist Committee: 2007 – Flight Path" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- 1 2 Fitzpatrick, J. W.; Lammertink, M; Luneau Jr, M. D.; Gallagher, T. W.; Harrison, B. R.; Sparling, G. M.; Rosenberg, K. V.; Rohrbaugh, R. W.; Swarthout, E. C.; Wrege, P. H.; Swarthout, S. B.; Dantzker, M. S.; Charif, R. A.; Barksdale, T. R.; Remsen Jr, J. V.; Simon, S. D.; Zollner, D (2005). "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America" (PDF). Science 308 (5727): 1460–2. doi:10.1126/science.1114103. PMID 15860589.

- ↑ "Wildlife Group Proposes $10,000 Reward For Ivory-billed Evidence". Eyewitness News everywhere. Clear Channel Broadcasting. 21 June 2006. Archived from the original on 28 August 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ Hill, Geoffrey E.; Mennill, Daniel J.; Rolek, Brian W.; Hicks, Tyler L. & Swiston, Kyle A. (2006): Evidence Suggesting that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (Campephilus principalis) Exist in Florida. Avian Conservation and Ecology – Écologie et conservation des oiseaux 1(3): 2. HTML fulltext PDF fulltext with links to appendices Erratum

- 1 2 Robert C. Fleischer, Jeremy J. Kirchman, John P. Dumbacher, Louis Bevier, Carla Dove, Nancy C. Rotzel, Scott V. Edwards, Martjan Lammertink, Kathleen J. Miglia & William S. Moore (2006). "Mid-Pleistocene divergence of Cuban and North American ivory-billed woodpeckers". Biology Letters 2 (3): 466–469. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0490. PMC 1686174. PMID 17148432.

- ↑ Leonard, Pat; Chu, Miyoko (Autumn 2006). "DNA Fragments Yield Ivory-bill's Deep History". BirdScope (Cornell Lab of Ornithology) 20 (4). Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ↑ Jackson, Jerome (2002). "Ivory-billed Woodpecker". Birds of North America Online.

- ↑ Winkler, Hans; Christie, David A. and Nurney, David (1995) Woodpeckers: An Identification Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World. Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-72043-1

- ↑ Hoose, Phillip M. (2004). The Race to Save the Lord God Bird. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-374-36173-8.

They gave it names like 'Lord God bird' and 'Good God bird'.

- ↑ Steinberg, Michael K. (2008). Stalking the Ghost Bird: The Elusive Ivory-Billed Woodpecker in Louisiana. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3305-7.

Nicknamed the 'Lord God Bird', the 'Grail Bird', 'King of the Woodpeckers', and 'Elvis in Feathers', the ivory-bill – thought to be extinct since the 1940s – fascinates people from all walks of life and has done so for centuries.

- ↑ Jackson, Jerome (2002). "Ivory-billed Woodpecker". Birds of North America Online. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ Allen, Arthur A. and Kellog, P. Paul (1937). "Recent Observations on the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker". Auk 54 (2): 164–184. doi:10.2307/4078548. JSTOR 4078548.

- ↑ "Ecology and Behavior". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ↑ "Studying a Vanishing Bird". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ↑ "History of the Ivorybill: The Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis), one of the largest woodpeckers known ... has become elusive to ornithologists as well as birdwatchers". ivorybill.org. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ↑ Weidensaul, Scott (2005): Ghost of a chance. Smithsonian Magazine. August 2005: 97–102.

- ↑ Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records (Mss. 4171), Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA (accessed 02/18/2015)<http://cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/Tensas/>

- ↑ Morris, Tim (9 January 2006). "the grail bird". lection. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ Mendenhall, Matt (2005). "Reported Ivory-bill Sightings Since 1944". Birders World Magazine. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ Mayell, Hillary (20 February 2002). ""Extinct" Woodpecker Still Elusive, But Signs Are Good". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, John W. (Summer 2002). "Ivory-bill Absent from Sounds of the Bayous". Birdscope. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ reference needed

- ↑ "Listening for the Ivory-bill". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Summer 2005. Archived from the original on 10 October 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ Dalton, Rex (2 August 2005). "Ivory-billed woodpecker raps on". BioEd Online. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- 1 2 Jackson, J. A. (2006). "Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis): Hope, and the Interfaces of Science, Conservation, and Politics" (PDF). The Auk 123: 1. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[0001:IWCPHA]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, J. W.; Lammertink, M.; Luneau, M. D.; Gallagher, T. W.; Harrison, B. R.; Sparling, G. M.; Rosenberg, K. V.; Rohrbaugh, R. W.; Swarthout, E. C. H.; Wrege, P. H.; Swarthout, S. B.; Dantzker, M. S.; Charif, R. A.; Barksdale, T. R.; Remsen, J. V.; Simon, S. D.; Zollner, D. (2006). "Clarifications about current research on the status of Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) in Arkansas". The Auk 123 (2): 587. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[587:CACROT]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Sibley, D. A. (2006). "Comment on "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America"" (PDF). Science 311 (5767): 1555a. doi:10.1126/science.1122778.

- 1 2 Fitzpatrick, J. W. (2006). "Response to Comment on "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in Continental North America"". Science 311 (5767): 1555b. doi:10.1126/science.1123581.

- ↑ Bevier, Louis (14 August 2007). "Ivory-billed debate". Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ Collinson, J Martin (March 2007). "Video analysis of the escape flight of Pileated Woodpecker Dryocopus pileatus: does the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Campephilus principalis persist in continental North America?". BMC Biology 5: 8. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-8. PMC 1838407. PMID 17362504.

- ↑ Jones, Clark D.; Jeff R. Troy; Lars Y. Pomara (June 2007). "Similarities between Campephilus woodpecker double raps and mechanical sounds produced by duck flocks". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119 (2): 259–262. doi:10.1676/07-014.1. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ "Ivory-billed woodpecker search season ends". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 18 May 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ "Refuge Opens Bayou DeView to Public Use". Cache River Nat'l Wildlife Refuge (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). 18 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ↑ Leonard, Pat (12 June 2007). "2006–07 Field Season Summary". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Leonard, Pat (27 June 2008). "2007–08 Ivory-billed Woodpecker Search Season Summary". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Leonard, Pat (7 January 2009). "Searching New Habitat: Ivory-bill Search Season Begins". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Lammertink, Martjan; Martin Piorkowksi (6 April 2009). "Out of the Everglades, Onward to South Carolina". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ↑ KUAF 91.3 National Public Radio (23 October 2009). "Search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Suspended". University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Archived from the original on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ Dalton, Rex (10 February 2010). "Still looking for that woodpecker". Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Hill, G. E., D. J. Mennill, B. W. Rolek, T. L. Hicks, and K. A. Swiston. (2006). "Evidence suggesting that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (Campephilus principalis) exist in Florida". The Resilience Alliance. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ↑ Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee (7 March 2007). "FOS BOARD REPORT—April 2007". Florida Ornithological Society. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ Hill, Geoff (2 August 2009). "Updates from Florida". Auburn University. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ↑ "Brinkley, Ark., Embraces 'The Lord God Bird'". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 6 July 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- ↑ "Sufjan Stevens – "The Lord God Bird" (MP3)". Npr.org. 2005-04-27. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

Further reading

- Audubon, John James LaForest (1835–38): The Ivory-billed Woodpecker. In: Birds of America 4. ISBN 0-8109-2061-1 (H. N. Abrams 1979 edition — the book itself is in the public domain)

- Farrand, John & Bull, John, The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region, National Audubon Society (1977)

- Gallagher, Tim W. (2005): The Grail Bird: Hot on the Trail of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Houghton Mifflin, Boston. ISBN 0-618-45693-7

- Jackson, Jerome A. (2004): In Search of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-58834-132-1

- Jackson, Jerome A (2006b). "The public perception of science and reported confirmation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Arkansas". Auk 123 (4): 1185–1189. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[1185:TPPOSA]2.0.CO;2.

- Mattsson, B. J.; Mordecai, R. S.; Conroy, M. J.; Peterson, J. T.; Cooper, R. J.; Christensen, H. (2008). "Evaluating the small population paradigm for rare large-bodied woodpeckers, with implications for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker". Avian Conservation and Ecology 3 (2): 5.

- National Audubon Society (2010): Watchlist entry for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker- Retrieved 2010-FEB-1.

- Tanner, James T. (1942). The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. National Audubon Society, N.Y.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2005). Once-thought Extinct Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Rediscovered in Arkansas. 28 April 2005 Press Release. Retrieved 2006-OCT-6.

- Winkler, H.; Christie, D. A. & Nurney, D. (1995): Woodpeckers: A Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. ISBN 0-395-72043-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Campephilus principalis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Campephilus principalis |

| External identifiers for Campephilus principalis | |

|---|---|

| Encyclopedia of Life | 917243 |

| GBIF | 13836099 |

| ITIS | 178264 |

| NCBI | 386521 |

| Also found in: Wikispecies, Arctos | |

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service draft recovery plan

- The Search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Cornell Lab of Ornithology website with video and sound files. Retrieved 2006-OCT-6.