Cambridge equation

The Cambridge equation formally represents the Cambridge cash-balance theory, an alternative approach to the classical quantity theory of money. Both quantity theories, Cambridge and classical, attempt to express a relationship among the amount of goods produced, the price level, amounts of money, and how money moves. The Cambridge equation focuses on money demand instead of money supply. The theories also differ in explaining the movement of money: In the classical version, associated with Irving Fisher, money moves at a fixed rate and serves only as a medium of exchange while in the Cambridge approach money acts as a store of value and its movement depends on the desirability of holding cash.

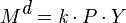

Economists associated with Cambridge University, including Alfred Marshall, A.C. Pigou, and John Maynard Keynes (before he developed his own, eponymous school of thought) contributed to a quantity theory of money that paid more attention to money demand than the supply-oriented classical version. The Cambridge economists argued that a certain portion of the money supply will not be used for transactions; instead, it will be held for the convenience and security of having cash on hand. This portion of cash is commonly represented as k, a portion of nominal income (the product of the price level and real income),  ). The Cambridge economists also thought wealth would play a role, but wealth is often omitted from the equation for simplicity. The Cambridge equation is thus:

). The Cambridge economists also thought wealth would play a role, but wealth is often omitted from the equation for simplicity. The Cambridge equation is thus:

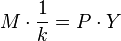

Assuming that the economy is at equilibrium ( ),

),  is exogenous, and k is fixed in the short run, the Cambridge equation is equivalent to the equation of exchange with velocity equal to the inverse of k:

is exogenous, and k is fixed in the short run, the Cambridge equation is equivalent to the equation of exchange with velocity equal to the inverse of k:

History and significance

The Cambridge equation first appeared in print in 1917 in Pigou's "Value of Money".[1] Keynes contributed to the theory with his 1923 Tract on Monetary Reform.

The Cambridge version of the quantity theory led to both Keynes's attack on the quantity theory and the Monetarist revival of the theory.[2] Marshall recognized that k would be determined in part by an individual's desire to hold liquid cash. In his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes expanded on this concept to develop the idea of liquidity preference,[3] a central Keynesian concept.