California High-Speed Rail

|

Artist's rendering of a TGV-Type California High-Speed Rail trainset with livery; this type of train is used in all CHSRA materials, but since the exact model of trainset to be acquired is not known, this is only illustrative | |

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Area served | Cities of the San Francisco peninsula, Santa Clara Valley, major population centers of the San Joaquin Valley, Antelope Valley, San Fernando Valley, & Los Angeles Basin |

| Locale | State of California |

| Transit type | High-speed rail |

| Number of stations | 24 (proposed) |

| Chief executive | Jeff Morales |

| Website |

www |

| Operation | |

| Operator(s) | A private operator to be determined |

| Technical | |

| System length | 800+ mi (1,300+ km) (proposed)[1] |

| No. of tracks | fully double-tracked plus 2 extra pass-through tracks in stations |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) |

| Electrification | Fully electric |

| Top speed |

220 mph (350 km/h) from San Jose to LA (about 422 mi (679 km)) |

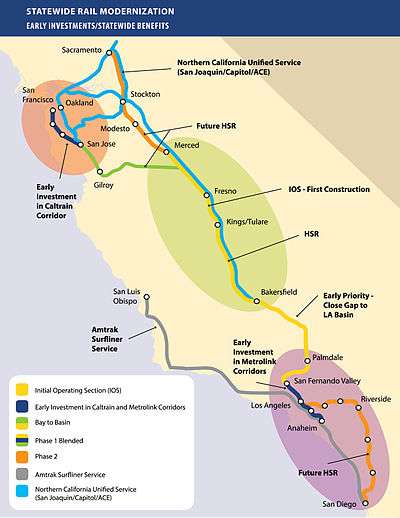

California High-Speed Rail is a high-speed rail system currently under construction in the state of California. By the end of Phase 1, the route will connect Los Angeles with San Francisco at speeds up to 220 miles per hour (350 km/h), providing a "one-seat ride" for the trip in 2 hours and 40 minutes. The system is required to operate without a subsidy, and to connect the state's major cities in the Bay Area, Central Valley, and Southern California.[4]

Construction on the initial section from Merced to Bakersfield began in 2015 and is expected to end in 2019, after which it is proposed that the Amtrak San Joaquin train may use the HSR tracks for faster conventional rail service. High-speed rail service is expected to begin in 2022 after the rails are extended south to Burbank.[5] Phase 1 is planned to be completed in 2029. In Phase 2 (no timetable as yet), the system will be extended northerly (through the Central Valley to Sacramento) and southerly (through the Inland Empire to San Diego), reaching all the major population centers specified in Proposition 1A (2008).[6] Construction is only fully funded through 2019, although the project is now automatically getting cap-and-trade funding amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

With an anticipated construction and planning cost of $68.4 billion (in year-of-expenditure dollars) for Phase 1, the project is the most expensive public works project in United States history.[7]

The project is managed by CHSRA (the California High-Speed Rail Authority), a state agency run by a board of governors.

By March 2016 the Authority will release its 2016 Business Plan. This will provide an updated construction cost figure (based on better data) as well as provide the Authority's latest plan how to get as quickly as possible to the Initial Operating Segment. There has also been recent discussion that it might switch to a Northern (Bay Area) to Central Valley IOS rather than a Southern (San Fernando Valley) to Central Valley IOS. That issue, and other current thinking, are discussed in L.A. first, or Bay Area? State rethinks high-speed train route options, an article in the Fresno Bee.

System route and speed requirements

AB 3034, the authorizing legislation for Proposition 1A (which was submitted to the voters and approved), specified certain route and travel time requirements. Among these were that the route must (1) link downtown San Francisco with Los Angeles and Anaheim, and (2) link the state's major population centers together "including Sacramento, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Central Valley, Los Angeles, the Inland Empire, Orange County, and San Diego." The first phase of the project must link San Francisco with Los Angeles and Anaheim. Up to 24 stations were authorized for the completed system.

This system will be built in two phases. Phase 1 will be about 520 miles (840 km) long, and is planned to be completed in 2029, connecting the downtowns of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Anaheim using high-speed rail through the Central Valley.[8] In Phase 2, the route will be extended in the Central Valley north to Sacramento, and from Los Angeles east through the Inland Empire and then south to San Diego. The total system length will be about 800 miles (1,300 km) long. Phase 2 has no dates as yet.

The Initial Construction Segment (ICS) of high-speed tracks runs from Merced to Bakersfield in the Central Valley. Simultaneously with the ICS construction, there are "bookend" and connectivity investments[9] including electrification of the San Francisco Peninsula Corridor used by Caltrain, improvements to tracks and signaling for Metrolink in the LA area and Caltrain, and better passenger interconnections for Caltrain, Amtrak, and other Northern California rail lines.

With regard to train speed and travel times, the train must also be electric and capable of a sustained operating speed of no less than 200 miles per hour (320 km/h). There are also a number of travel time benchmarks. The ones applicable to Phase 1 of the project are: (1) a maximum nonstop travel time between San Francisco and San Jose of 30 minutes, and (2) a maximum nonstop travel time between San Jose and Los Angeles of 2 hours and 10 minutes. (Thus, a nonstop time from San Francisco to Los Angeles in 2 hours and 40 minutes.)

Phase 1

Completion timeline

By 2018: The Initial Construction Segment (ICS) is to be completed — 130 miles (210 km) — Merced to Bakersfield.

- Provide faster service on the Amtrak San Joaquin train in the southern and central parts of the Central Valley, connecting with BNSF tracks at the north end.

By 2022: Initial Operating Section (IOS) is to be completed — 300 miles (480 km) — Merced to Burbank[6]

- Provide a one-seat HSR ride between Merced and Burbank.

- Close the north-south rail gap to link the Los Angeles Basin with the Central Valley and Northern California.

- Construct up to 130 miles of high-speed rail track and supporting structures in the Central Valley.

- Select a private sector system operator.

- Gain ridership and revenues to attract private capital for system expansion.

- Connect with upgraded regional and local rail lines for blended operations and shared ticketing.

By 2027: Bay to Basin is to be completed — 410 miles (660 km) — San Jose & Merced to Burbank

- Provide a one-seat HSR ride between San Francisco (Transbay Transit Center) and Burbank.

- Share an electrified, upgraded Caltrain corridor from San Jose to San Francisco (Transbay Transit Center).

By 2029: Phase 1 Blended is to be completed — 520 miles (840 km) — San Francisco to Los Angeles/Anaheim

- Provide a one-seat HSR ride between San Francisco (Transbay Transit Center) and Los Angeles (Union Station).

- Use dedicated high-speed rail tracks between San Jose and Los Angeles Union Station.

- Share an electrified, upgraded Caltrain corridor from San Jose to San Francisco (Transbay Transit Center).

- Share an upgraded Metrolink line from LA to Anaheim.

Stations and Connecting Services

All stations in this table represent proposed service. Station names in italics are optional stations that may not actually be constructed. In most cases existing stations are proposed to be used for HSR service, with the exception of completely new stations at Merced, Fresno, Kings–Tulare, and Bakersfield. All listed locations are in California.

Route details

(1) San Francisco to San Jose. The 51-mile (82 km)[10] bookend from San Francisco to San Jose currently used by Caltrain is scheduled to be electrified by 2020. High-speed trains will run at 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) on shared tracks beginning with Bay to Basin in 2026. The one-way fare between San Francisco and San Jose is expected to cost $22 in 2013 dollars.[11]

(2) San Jose to Merced / the Diablo Range crossing. The 125 miles (201 km) from San Jose to Merced, crossing the Pacheco Pass, will run at top speed on dedicated HSR tracks for Bay to Basin in 2026 (since the current right-of-way south of Tamien is freight-owned). This segment runs through the Chowchilla Wye. The one-way fare between San Jose and Merced is expected to cost $54 in 2013 dollars.[11]

One issue initially debated was the crossing of the Diablo Range via either the Altamont Pass or the Pacheco Pass to link the Bay Area to the Central Valley. On November 15, 2007, Authority staff recommended that the High-Speed Rail follow the Pacheco Pass route because it is more direct and serves both San Jose and San Francisco on the same route, while the Altamont route poses several major engineering obstacles, including crossing San Francisco Bay. Some cities along the Altamont route, such as Pleasanton and Fremont, opposed the Altamont route option, citing concerns over possible property taking and increase in traffic congestion.[12] However, environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, have opposed the Pacheco route because the area is less developed and more environmentally sensitive than Altamont.[13]

On December 19, 2007, the Authority Board of Directors agreed to proceed with the Pacheco Pass option.[14] Pacheco Pass was considered the superior route for long-distance travel between Southern California and the Bay Area, although the Altamont Pass option would serve as a good commuter route. The Authority plans conventional rail upgrades for the Altamont corridor, to complement the high-speed project.

This segment will also cross the Calaveras Fault.

(3) Chowchilla Wye. The Chowchilla Wye is located between Gilroy and the main HSR line running between Merced and Fresno in the Central Valley. The wye has two purposes. One is to be able to take trains coming from the Bay Area and turn them to go towards Sacramento, and vice versa. The other is to allow a train to reverse itself on the tracks (that is, to swap the ends). However, since one of the train specifications is that they be able to have cabs at each end and run in both directions, the need to reverse trains is greatly reduced.

(4) Merced to Fresno. The 60-mile (97 km) segment from Merced to Fresno in the Central Valley will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the Initial Operating Section in 2022.[15] The southern portion of this segment (north of Madera to Fresno) has already received route approval and is undergoing construction.

(5) Fresno to Bakersfield. The 114-mile (183 km) segment in the Central Valley will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the Initial Operating Section in 2022. As of 7 May 2014, the route for this segment has been chosen and approved by the California High-Speed Rail Authority.[16] Final route approval was obtained by the Federal Railroad Administration and the federal Surface Transportation Board in August 2014, so construction can proceed.[17] Note that due to disputes with the cities of Shafter and Bakersfield, the currently planned segment ends north of Shafter until final routes through Shafter and northern Bakersfield are negotiated with those cities. (Refer to the Initial Construction Section (ICS) above.)

(6) Bakersfield to Palmdale / the Tehachapi Mountains crossing. The 75 miles (121 km) from Bakersfield to Palmdale, crossing the Tehachapi Pass, will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the Initial Operating Section in 2022.[18]

In January 2012, the Authority released a study, started in May 2011, that favors a route over the Tehachapi Pass into Antelope Valley and Palmdale over one that parallels Interstate 5 from San Fernando Valley over the Tejon Pass into the Central Valley.[19] The route over the Tehachapi Mountains is still to be determined.

The low point on Tehachapi Pass is 4,031 feet (1,229 m). This is significantly higher than Pacheco Pass at 1,368 feet (417 m) over the Diablo Range, and so this is a more formidable engineering challenge. For comparison, the route over Pacheco Pass begins in Chowchilla (elevation 240 feet (73 m)), crosses the valley floor and climbs to the pass (elevation 1,368 feet (417 m)), and descends to Gilroy (elevation 200 feet (61 m)). The route over the Tehachapi Pass begins in Bakersfield (elevation 404 feet (123 m)), crosses the valley floor and climbs over steeper mountains to the pass (elevation 4,031 feet (1,229 m)), then descends to Palmdale (elevation 2,657 feet (810 m)).

Community meetings to solicit stakeholder concerns will take place until about the end of 2015.[20]

(7) Palmdale to Burbank / the San Gabriel Mountains crossing. The segment from Palmdale to Burbank will run on dedicated HSR tracks for the IOS in 2022.[21][22] The one-way high-speed rail fare between Palmdale and Los Angeles is expected to cost $31 in 2013 dollars.[11] This segment will cross numerous seismic fault lines;[23][24] this will include the San Andreas fault.[25] This segment will cross the San Gabriel Mountains.

The basic route from Palmdale (elevation 2,657 feet (810 m), north of the San Gabriel Mountains) to Burbank (elevation 607 feet (185 m), south of the San Gabriel Mountains) is still under discussion. There are two major route alternatives. The one initially considered, called the "State Route 14 Corridor", ran from Palmdale in the Antelope Valley down through the Santa Clarita Valley to Burbank in the San Fernando Valley, a distance of about 51 miles (82 km). More recently, the "East Corridor" has been proposed, a route composed almost entirely of tunnels running under the Angeles National Forest, a distance of about 35 miles (56 km).[26][27]

There is significant opposition by Santa Clarita Valley residents to the initial route,[28] and the under-the-mountains route would reduce travel time by about eight minutes, but would have additional Federal approval complications. There are still community stakeholder meetings proceeding, and as might be expected, there are also those who oppose the East Corridor alternative as well.[29]

The Palmdale to Burbank route and environmental considerations presentation (May 2015, PDF) is available. The alternatives analysis is not due until the summer of 2015, and the route decision is not expected until 2016.[30]

Proposed routes for the Palmdale-to-Burbank section are displayed and explained in a 26-minute Virtual Open House presentation. This not only displays the factors taken into account to create the proposed routes, there is a virtual flyover of the proposed routes, and scenes from the many community meetings which illustrate the public outreach efforts underway (May–June 2015).

(8) Burbank to Los Angeles. The approximately 12-mile (19 km) segment from Burbank to Los Angeles (LA Union Station) will run on dedicated HSR tracks for Phase 1 Blended in 2029.[31] The one-way fare between Burbank and Los Angeles is expected to cost $26 in 2013 dollars.[11][32]

(9) Los Angeles to Anaheim. The 29 miles (47 km) from Los Angeles to Anaheim will run on an upgraded Metrolink corridor for Phase 1 Blended in 2029. The one-way fare between Los Angeles and Anaheim is expected to cost $29 in 2013 dollars.[11][32]

XpressWest connection to Las Vegas

XpressWest is a company that since 2007 has been trying to build a high-speed rail line between Southern California and Las Vegas, Nevada, part of the "Southwest Rail Network" they hope to create. On Sept. 17, 2015 they announced formation of a joint venture with China Railway International USA, a consortium of Chinese firms that includes China Railway, the national Chinese railway company, to develop, finance, build, and operate the line. Initial funding of the venture is reported to be $100 million.

The rail line would begin in Las Vegas and cross the Mojave Desert stopping in Victorville, California and terminating in Palmdale, California (where it would connect with the CHSR line and Metrolink). This route would total about 230 miles (370 km). Lisa Marie Alley, speaking for CHSRA, said that there have been ongoing discussions concerning allowing the trains to use CHSRA lines to go further into the Los Angeles area, although no commitments have been made as yet. While many approvals have been obtained for the rail line from Victorville to Las Vegas, the section from Palmdale to Victorville has none as yet. Construction could begin in late 2016 on the Victorville to Las Vegas link.[33]

Phase 2

|

| |

|

|

There has been route planning for Phase 2, but no dates and no financing plans have been made. Proposition 1A requires that Phase 1 be completed before construction is started on Phase 2. The Phase 2 segments, Merced–Sacramento and Los Angeles–San Diego, total about 280 miles (450 km). The completed system length after these extensions are constructed will be about 800 miles (1,300 km).

As of 2015, the following stations and options are proposed. Existing train stations, if any, are linked. There is often a choice of alignments, some of which may involve the construction of a new station at a different location.

Sacramento extension. The 110 miles (177 km) segment from Merced to Sacramento will be built on dedicated HSR tracks and go to:

San Diego extension. The 167 miles (269 km) segment from Los Angeles to San Diego will be built on dedicated HSR tracks and go to:

- East San Gabriel Valley (El Monte, West Covina or Pomona)

- Ontario International Airport

- San Bernardino Transit Center + Riverside (March AFB); or alternatively Corona

- Murrieta

- Escondido Transit Center

- San Diego International Airport (Lindberg Field)

Trains (rolling stock)

Acquisition. In January 2015 the California High Speed Rail Authority issued an RFP (request for proposal) for rolling stock for complete trains (known as "trainsets"). The proposals received will be reviewed so that acceptable bidders can be selected, and then requests for bids will be sent out. The winning bidder will likely not be selected until 2016.

It is estimated that for the entire Phase 1 system up to 95 trainsets might be required.[34] Initially, however, only 16 trainsets are anticipated to be purchased.[35] Trainset expenses, according to the 2014 Business Plan, are planned at $889 million for the IOS (Initial Operating Segment) in 2022, $984 million for the Bay to Basin in 2027, and $1.4 billion for the completed Phase 1 in 2029, for a total of $3.276 billion.[21]

Nine companies have formally expressed interest in producing trainsets for the system.[36]

Specifications. In addition to many other requirements:[37]

- each trainset will have a sustained continuous speed of 220 miles per hour (350 km/h);

- a maximum testing speed of 242 miles per hour (389 km/h);

- a lifespan of at least 30 years;

- a length no longer than about 680 feet (210 m);

- the ability to operate two trainsets as a single "consist" (a long train);

- have control cabs at both ends of each trainset and the ability to go equally well in either direction;

- pass-by noise levels (82 feet (25 m) from track) not to exceed 88 dB at 155 miles per hour (249 km/h) and 96 dB at 220 miles per hour (350 km/h)

- have at least 450 seats and carry 8 bicycles;

- have seating for first class and business class passengers as well as have space for wheelchairs;

- have food service similar to airplane style serving;

- allow for use of cellphones, broadband wireless internet access, and onboard entertainment services;

- have a train communications network to notify passengers of travel/train/station/time information;

- and also have earthquake safety systems for safe stopping and exiting.

One specification that is causing some difficulty is the HSR train requirement for a floor height of 50 in. (127 cm) above the rails. This is the international standard for high-speed rail trains, however, Caltrain trains have a floor height of only 25 in. (63.5 cm). (Metrolink trains have a similar issue.) In October 2014 Caltrain and the Authority agreed to work together to try to implement "level-boarding" on the shared station platforms.[38]

One solution to this that Caltrain is pursuing is to have doors in their trainsets at two heights (one for each platform height). However, this will reduce seated passenger capacity in the trainsets by an estimated 78 to 188 seats per six-car train. The Authority is also resisting the idea of lowering their trainset floor height.[39]

Anticipated benefits

In addition to the direct reduction in travel times the HSR project will produce, there are other anticipated benefits, both general to the state, to the regions the train will pass through, and to the areas immediately around the train stations.

Statewide economic growth and job creation. In 2009, the Authority projected that construction of the system will create 450,000 permanent jobs through the new commuters that will use the system,[40] and that the Los Angeles-San Francisco route will generate a net operating revenue of $2.23 billion by 2023,[40] consistent with the experience of other high-speed intercity operations around the world.[41] The 2012 Economic Impact Analysis Report by Parson Brinkerhoff (project managers for the Authority) also indicated substantial economic benefits from high-speed rail.

Even Amtrak's high-speed Acela Express service generates an operating surplus that is used to cover operating expenses of other lines.[42]

The 2012 Business Plan also estimates that the Initial Construction Segment (ICS) construction will "generate 20,000 jobs over five years," with the Phase 1 system requiring 990,000 job-years over 15 years, averaging 66,000 annually.[43]

Environmental benefits. According to a fact sheet on the Authority website[44] the environmental benefits of the system include:

- In 2022, when the Initial Operating Section (Merced to the San Fernando Valley) is up and running, the resulting greenhouse gas reductions will be between 100,000 to 300,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the first year. That’s the equivalent of from between 17,700 to 53,000 personal vehicles taken off the road.

- Between 2022 and 2040, the cumulative reduction of CO2 is estimated to be between 5 and 10 million metric tons. By 2040, the system is estimated to reduce vehicles miles of travel in the state by almost 10 million miles of travel every day (16,000,000 km).

- Over a 58-year period (from the start of operations in 2022 through 2080), the system is estimated to reduce auto travel on the state’s highways and roads by over 400 billion miles of travel (6.4×1011 km).

Regional benefits. In its 67-page ruling in May 2015, the federal Surface Transportation Board noted: "The current transportation system in the San Joaquin Valley region has not kept pace with the increase in population, economic activity, and tourism. ... The interstate highway system, commercial airports, and conventional passenger rail systems serving the intercity market are operating at or near capacity and would require large public investments for maintenance and expansion to meet existing demand and future growth over the next 25 years or beyond."[45] Thus, the Board sees the HSR system as providing valuable benefits to the region's transportation needs.

The San Joaquin Valley is also one of the poorest areas of the state. For example, the unemployment rate near the end of 2014 in Fresno County was 2.2% higher than the statewide average.[46] And, of the five poorest metro areas in the country, three are in the Central Valley.[47] The HSR system has the potential to significantly improve this region and its economy. A large January 2015 report to the CHSRA examined this issue.[48]

In addition to jobs and income levels in general, the presence of HSR is expected to benefit the growth in the cities around the HSR stations. It is anticipated that this will help increase population density in those cities and reduce "development sprawl" out into surrounding farmlands.[49]

Public opinion and peer review

There are two significant types of criticism. One is the legally established "peer review" process that the legislature established for an independent check on the Authority's planning efforts.[50] The other are public criticisms by groups, individuals, public agencies, and elected officials.

It should be also noted that not all issues to get the HSR system in place have been resolved. There are still real concerns remaining, as some of the following criticisms will show. It should also be noted that this is a large, complex project, and it is entirely normal that not all issues will be resolved before significant investment has been made in construction. Critics tend not be optimistic that the remaining issues will be resolved satisfactorily. In the end, there is no clear evidence one way or the other that the project can be completed satisfactorily or not. This is where the proponents talk about the American "can-do" spirit, and because the overall framework is sound, the remaining issues can be resolved. Dan Richard, the chair of the Authority, even said this at the Bold Bets: California on the Move? conference in February 2015 hosted by The Atlantic magazine and Siemens.[51]

Peer review

California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group. The California Legislature established the California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group to provide independent analysis of the Authority's business plans and modeling efforts.[50] These documents are submitted to the Legislature as needed. The most recent analyses are Comments on the 2014 Business Plan and Sept. 2015 SemiAnnual Update.

Key points in the Business Plan review include:

- Modeling has been improved, but there is a lack of practical experience to inform them, and the participation of potential stakeholders (businesses and investors) would be beneficial.

- The improved forecasts and estimates still have significant uncertainty.

- Future funding sources are still uncertain for meeting projected needs.

- The blended system approach raises issues that need resolution (Caltrain platform heights and train floor heights, extra high electric catenaries for freight car clearance, use of Caltrain's CBOSS system of Positive Train Control by HSR trains, and possible increased dangers of higher speed trains at non-separated road crossings).

- There is a need for improvements in the forthcoming 2016 Business Plan (specifically, the omission of Norwalk and Anaheim passenger demand, boardings, and revenues), and recommendation for re-evaluation of the operation of the LAUS to Anaheim link.

Professional studies. Two peer studies have recently been made of station siting and design in Europe.

Eric Eidlin, an employee of the Federal Transit Administration (Region 9, San Francisco), in 2015 wrote a study funded by the German Marshall Fund of the United States comparing the structural differences of the three relative to HSR and their historical development.[52] He also focused on the issue of station siting, design, use, and impact on the surrounding community. From this, he developed ten recommendations for CASHRA. Among these are:

- Develop bold, long-term visions for the HSR corridors and stations.

- Where possible site HSR stations in central city locations.

- In rural areas emphasize train speed, in urban areas emphasize transit connectivity.

- Plan for and encourage the non-transit roles of the HSR stations.

Eidlin's study also notes that in California there has been debate on the disadvantages of the proposed blended service in the urban areas of San Francisco and Los Angeles, including reduced speeds, more operating restraints, and complicated track-sharing agreements. However, there are some inherent advantages in blended systems that have not received much attention: shorter transfer distances for passengers, and reduced impacts on the neighborhoods.

A July 2015 study by A. Loukaitou-Sideris, D. Peters, and W. Wei of the Mineta Transportation Institute at San Jose State College compared the rail systems of Spain and Germany, and how blended high-speed rail lines have succeeded there.[53] Emphasis was also given to station siting, design, and use. Similarly to Eidlin's study, they found that the best stations not only provided high connectivity, but they also had a broader role by providing shops and services to community members as well as travelers.

Public criticisms

The California High-Speed Rail system has been criticized on budgetary, feasibility, legal, environmental, political, and public opinion grounds. Criticisms have been made by individuals, public officials, private institutions, government agencies, and civil society organizations.

Reason Foundation, the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, and the Citizens Against Government Waste published a large study (called the Due Diligence Report) critiquing the project in 2008.[54] In 2013 Reason Foundation published an Updated Due Diligence Report.[55] Key elements of the updated critique include

- unachievable train speed

- implausible ridership projections

- spiraling costs

- no funding plan

- incorrect assumptions re HSR alternatives

- increasing fare projections

This critique is based on the 2012 Business Plan. Although the 2012 Business Plan has been superseded by the 2014 Business Plan, the critique does include the Blended System approach using using commuter trackage in SF and LA.

James Fallows in The Atlantic magazine succinctly summarized all the public criticisms thus, "It will cost too much, take too long, use up too much land, go to the wrong places, and in the end won't be fast or convenient enough to do that much good anyway."[56]

Alternatives to HSR. Some have offered the idea that instead of risking the large expenditures of high-speed rail, that existing transportation methods be increased to meet increased transportion needs. However, in a report[57] commissioned by the Authority, a comparison was made to the needed infrastructure improvements if high-speed rail were not constructed. According to the report, the cost of building equivalent capacity to the $68.4 billion (YOE) Phase 1 Blended plan, in airports and freeways, is estimated to be $119.0 billion (YOE) for 4,295 new lane-miles (6,912 km) of highway, plus $38.6 billion (YOE) for 115 new airport gates and 4 new runways, for a total estimated cost of $158 billion.[57]

"Hyperloop" is an alternative system that Elon Musk has championed. He has criticized the high-speed rail project as too expensive and not technologically advanced enough (trains that are too slow). On August 12, 2013 he released a high-level alpha design for a Hyperloop transit system concept which he claimed would travel over three times as fast and cost less than a tenth of the rail proposal.[58][59] The following day he announced a plan to construct a demonstration of the concept.[60] Musk's claims have been subject to significant debate and criticism, in particular that the costs are still unknown and likely understated, the technology is not proven enough for statewide implementation, the route proposed doesn't meet the needs of providing statewide transportation, and it does not meet the legal requirements of Proposition 1A and so would require a whole new legal underpining.[61]

Project budget concerns. The project's cost and scope have long been a source of controversy. The Authority has estimated the project's year-of-expenditure cost at $68.4 billion (2012 estimate).[62] In July 2014 The World Bank reported that the per kilometer cost of California's high-speed rail system was $56 million, more than double the average cost of $17–21 million per km of high speed rail in China and more than the $25–39 million per km average for similar projects in Europe.[63] It should be noted, though, that high real estate prices in California and three mountain ranges to cross contribute to the difference. For example, Construction Package 2-3 in the farmland of the flat Central Valley works out to $11.4 million per km, although this figure does not include electrification or property values, so it's roughly comparable internationally. Furthermore, the proposed HSR 2 in Great Britain is estimated to be more expensive on a per mile basis than the Californian system.

The California Legislative Analyst's Office published recommendations on May 10, 2011, which they said will help the high-speed rail project be developed successfully. They recommended that the California legislature seek flexibility on use of federal funds and then reconsider where construction of the high-speed rail line should start. They also recommended that the California legislature shift responsibility away from the Authority and fund only the administrative tasks of the Authority in the 2011–12 budget.[64]

In January 2012, an independent peer review panel published a report recommending the Legislature not approve issuing $2.7 billion in bonds to fund the project.[65] The panel of experts was created by state law to help safeguard the public's interest. The report said that moving ahead on the high-speed rail project without credible sources of adequate funding represents a financial risk to California.

Prior to the July 2012 vote, State Senator Joe Simitian, (D-Palo Alto), expressed concerns about financing needed to complete the project, asking: "Is there additional commitment of federal funds? There is not. Is there additional commitment of private funding? There is not. Is there a dedicated funding source that we can look to in the coming years? There is not."[66] The lobbying and advocacy group Train Riders Association of California also considers that Bill SB 1029 "provides no high-speed service for the next decade".[67]

The 2008 Due Diligence Report projected that the final cost for the complete system would be $65.2 to $81.4 billion (2008), significantly higher than estimates made for the Authority by Parsons Brinckerhoff, an American engineering firm. However, the Authority is using Design-Build construction contracts to counter the tendency toward cost over-runs. All of the construction is to be done via "design-build" proposals wherein each builder is given leeway in the design and management of construction, but not the ability to run back with contract change orders except for extraordinary problems. The builder is given specifications but also given the freedom to meet them in their own way, plus the ability to modify the construction plans in an expeditious and cost-effective manner.[68] As of May 2015, both construction packages awarded have come in significantly under staff estimates. For example, Construction Package 1 came in 20% under staff estimates ($985 million versus $1.2 billion),[69] and Construction Package 2-3 came in under by 17% to 28% ($1.234567 billion versus $1.5-$2 billion)

Ridership and revenue concerns. In May, 2015, the Los Angeles Times published an article by critics on the estimated operational revenue of the system in "Doing the math on California's bullet train fares".[70] The article raised a number of doubts that the system could be self-supporting, as required by Prop 1A, and ended by quoting Louis Thompson (chairman of an unnamed state-created review panel) who said "We will not know until late in the game how everything will turn out."[56]

The Due Diligence Report in 2008 projected fewer riders by 2030 than officially estimated: 23.4 to 31.1 million intercity riders a year instead of the 65.5 to 96.5 million forecast by the Authority and later confirmed by an independent peer review.[71]

However, Robert Cruickshank of the California High Speed Rail Blog (which closely watches the project and advocates for it) countered by raising numerous critiques of data and conclusions in the article in his article "LA Times Completely Botches Story of HSR Fares".[72] In addition, readers of his blog submitted evidence that the data given for some of the comparison fares were seriously in error.[73]

The Authority's ridership estimates initially were unrealistically high, and have been revised several times using progressively better estimating models, including risk analysis and confidence levels. These now use generally recognized international standard methods.[74] The 2014 study (at a 50% confidence level) estimated the following ridership/revenue figures:

2022 (IOS): 11.3 million riders / $625 million

2027 (Bay to Basin): 19.1 million riders / $1055.6 million

2029 (Phase 1 initial): 28.4 million riders / $1350.4 million

2040 (Phase 1 mature): 33.1 million riders / $1559.4 million[75]

Travel time concerns. There have been some comments by critics (such as the Due Diligence Report noted above) that the proposed system will not meet the Proposition 1A requirement of downtown San Francisco to Los Angeles travel time of 2 hours and 40 minutes.

The Authority's plan is close to the requirement, but does push the limits of conventional HSR speed.

- San Francisco to San Jose nonstop at 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) for (57 miles (92 km)) = 31 min. (note 30 min. is required).

- San Jose to Los Angeles nonstop at 220 miles per hour (350 km/h) for (417 miles (671 km) or 437 miles (703 km)) = 1 hr. 54 min. or 1 hr. 59 min. (note 2 hr. 10 min. is required). Even at a slower 200 miles per hour (320 km/h) the times would be 2 hrs. 5 min. or 2 hrs. 11 min.

Both the 2008 and 2013 Due Diligence reports state that no existing high-speed system currently meets the proposed operation speed and safety goals. It notes that the highest cruising HSR speed in the world on production runs is about 200 miles per hour (320 km/h) in France, and this is significantly less than the sustained speed of 220 miles per hour (350 km/h) the CHSRA plan requires. They also note safety concerns in running at top speed through highly populated urban areas such as Fresno.[55] However, for three years Chinese HSR trains ran at 217 miles per hour (349 km/h), but the speeds were reduced due to safety concerns and . mostly - costs.[76] In fact a Siemens Velaro trainset without any modifications has posted a speed record well in excess of 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph), though economic considerations keep them limited to 320 kilometres per hour (200 mph) in revenue service.

The current trainset specification requires sustained speeds of 220 miles per hour (350 km/h). So, ultimately it is up to the trainset manufacturers to meet the Authority's speed requirement, since the proposed route and speed do meet the Proposition 1A requirements. It is worth noting that China has created a new operating speed standard of 380 kilometres per hour (240 mph) on its main HSR lines, which trains such as the Chinese CRH380 (manufactured in cooperation with Bombardier Sifang (Qingdao) Transportation Ltd), are capable. The UK's High Speed 2 also specifies a higher operation speed of 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph).

Legality concerns. In December 2011 Legislative Analyst's Office published a report indicating that the incremental development path outlined by CHSRA may not be legal.[77] According to the State Analyst, "Proposition 1A identifies certain requirements that must be met prior to requesting an appropriation of bond proceeds for construction. These include identifying for a corridor, or a usable segment thereof, all sources of committed funds, the anticipated time of receipt of those funds, and completing all project-level environmental clearances for that segment. Our review finds that the funding plan only identifies committed funding for the ICS (San Joaquin Valley segment), which is not a usable segment, and therefore does not meet the requirements of Proposition 1A. In addition, the HSRA has not yet completed all environmental clearances for any usable segment and will not likely receive all of these approvals prior to the expected 2012 date of initiating construction."

However, initial concerns regarding the projects legality have (as of May 2015) been put to rest. (See Legality under History, above.)

Central Valley and Pacheco Pass route concerns. Some people are concerned with the Valley route, in particular its going down the east side of the Central Valley rather than the more open west side. Citizens for California High-Speed Rail Accountability note: "Environmental lawsuits against the California High-Speed Rail Authority often claim inadequate consideration of running the track next to Interstate 5 in the Central Valley or next to Interstate 580 over the Altamont Pass."[78]

The Pacheco Pass alignment going through the Grasslands Ecological Area, has been criticized by two environmental groups; The Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council.[79] A coalition that includes the cities of Menlo Park, Atherton, and Palo Alto has also sued the Authority to reconsider the Altamont Pass alternative.[80][81] More than one hundred land owners along the proposed route have rejected initial offers by the Authority, and the Authority has taken them to court, seeking to take their land through eminent domain.[82][83][84] The possibility of urban sprawl into communities along the route have been raised by farming industry leaders.[85]

San Fernando Valley opposition. On Thursday, May 28, 2015 the CHSRA held an open house meeting in the City of San Fernando to discuss the route into the Valley and the impacts of the proposed rail service, and found opposition by angry protesters, including city officials. Residents and officials of other affected cities in the Valley also have serious concerns. The Authority says it is committed to making this work, and to involving the communities to select the best route, but there are many factors to consider in selecting the route. Michelle Boehm, the Southern California section director of the project, said that the route would be selected over the next 12 to 18 months, and issue a final environment report in two years. The next community meeting will be in downtown Los Angeles on June 9, and is also expected to draw many protesters.[86]

Property acquisition delays. The effect of property acquisition delays has created some serious concerns, and there is a September 30, 2017 deadline to spend the federal stimulus money of nearly $4 billion.[87]

The Construction Package 1 contract was signed in August 2013, yet not all the property necessary has been acquired in a timely manner, which has seriously slowed down the work. In March 2015, the contractor, Tutor Perini, sought additional funds due to the added expense of delays.[88]

As of June 2015, about 260 properties had been acquired of the nearly 1,100 needed (in whole or in part) for the first two construction sections.[89] Since December 2013, 259 resolutions of necessity have been adopted by the state's Public Works Board, the necessary step before issuing eminent domain resolutions and acquiring the land through litigation. By July 2015, the pace of acquisition was clearly speeding up with the increasing pace at which the state adopted its eminent domain resolutions.[90]

Public opinion surveys

The PPIC March 2015 Survey indicated that support for the project has hovered around 50% since 2012. In 2015, when asked if they favor or oppose the project, then 47% favor it, and 48% oppose it. When asked how they feel if the project cost less, favorability rises to 64%. When asked how important high-speed rail is, then 64% of respondents said very or somewhat important, and 35% said not too or not at all important. Dan Richard, chair of the Authority, says in an interview with James Fallows that he believes approval levels will increase when people can start seeing progress, and trains start running on the tracks.[51]

History

Financing summary

In 1996 the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA), was established to begin formal planning in preparation for a ballot measure in 1998 or 2000.[91] The ballot measure was originally scheduled to be put before voters in the 2004 general election; however, the state legislature voted twice to move it back, first to 2006, and finally to 2008 when 52.7% of voters approved the issuing of $9 billion in bonds for high speed rail in Proposition 1A,[92] a measure to construct the initial segment of the network. The measure authorized $9.95 billion in bond sales for the construction of the core segment between San Francisco and Los Angeles/Anaheim, and an additional $950 million for improvements on local railroad systems, which will serve as feeder systems to the planned high-speed rail system.

On January 28, 2010, the White House announced that California would receive $2.35 billion of its ARRA (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009) request, of which $2.25 billion was allocated specifically for California High Speed Rail, while the rest was designated for conventional rail improvements.[93] Over the course of 2010 and 2011, the federal government awarded the Authority a further $4 billion in high-speed rail funding, mainly from states that had rejected it such as Florida.[94][95][96]

On July 6, 2012, the California legislature approved construction of high-speed system, and Gov. Jerry Brown signed the bill on July 18.[97][98]

In June 2014 state legislators and Governor Jerry Brown agreed on apportioning the state's annual cap-and-trade funds so that 25% goes to high speed rail (under the authority of CHSRA) and 15% goes to other transportation projects by other agencies.[99] The state's Legislative Analyst's Office estimated that cap-and-trade income in 2015 and 2016 could total $3.7 billion, of which $925 million would be allocated to HSR.[100]

On Sept. 30, 2015, the Authority posted the names of 30 large firms who were interested in financing, constructing, and operating the California HSR system. Further discussions were planned to be held with each of them in the following two months.[101]

As of mid-2015, current funds allocated for designing and constructing the system total $6.302 billion, with another $2.024 billion for connectivity and bookend transportation projects. (Refer to History of California High-Speed Rail for details).

Legal challenges summary

The Proposition 1A compliance suit (John Tos, Aaron Fukuda, and the Kings County Board of Supervisors v. California High-Speed Rail Authority) concerned the issue that the Authority was not properly complying with the law. It was first filed in late 2011. The final ruling was that the requirements for the financing plan, environmental clearances, and construction plans did not need to be secured for the entire project before construction began, but only for each construction segment.

However, the case was split into two parts, and the second part of the case is still continuing with a trial date of Feb. 11, 2016. The issues still to be decided concern three Proposition 1A legal requirements: (1) Can the train travel from Los Angeles (Union Station) to San Francisco (Transbay Terminal) in two hours and 40 minutes? (2) Will the train require an operational subsidy? (3) Does the new "blended system" approach meet the definition of high-speed rail in Proposition 1A? This lawsuit is discussed August 3 and 21, 2015 in the Fresno Bee.[102][103]

On December 15, 2014 the federal Surface Transportation Board determined (using well-understood preemption rules) that its approval of the HSR project in August "categorically preexempts" lawsuits filed under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). However, this supposition is still being tested in the California courts in a similar case, Friends of Eel River v. North Coast Railroad Authority.[104]

Refer to History of California High-Speed Rail for more details and other legal issues.

Construction summary

On December 2, 2010, the Authority Board of Directors voted to begin construction on the first section of the system from Madera to Fresno, known as the Initial Construction Segment (ICS). With the Design-Build contractual system the Authority is using, the contractor will be responsible for the final construction design elements.[51] Due to the infusion of additional federal funds reallocated from states that canceled their high-speed rail plans, the initial segment of construction was extended south to Bakersfield in 2010, and north to the future Chowchilla Wye (where trains can be turned) in 2011.[105]

A groundbreaking ceremony was hosted in Fresno on January 6, 2015 to mark the commencement of sustained construction activities.[106]

Construction packages 1, and 2–3 have been let and are currently under construction. In Oct. 2015 a contract was awarded for project management and oversight of the CP 4 construction, which is to be let in 2016[107] The bids for CP-4 were received, and in Jan. 2016 a bidder has been selected for the next construction segment.

Refer to History of California High-Speed Rail for details of these.

See also

- California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA), the governing board of the California HSR project.

- Proposition 1A (2008), the public approval and bond authorization for California HSR.

- XpressWest, formerly DesertXpress, a planned high-speed rail from Victorville to Las Vegas.

- Hyperloop, a still-theoretical high speed transit system that does not use rail technology.

Further reading

- CHSRA's 2014 Business Plan describes the latest project goals, financing, and development plans. (SB 1029 (enacted in 2012) requires the Authority to produce a revised business plan every two years.[98])

- CHSRA's March 2015 Project Update details the current status of the project. (SB 1029 also requires that twice a year, on March 1 and November 15, the Authority provide a project status report.)

- James Fallows in The Atlantic magazine wrote a series of 17 articles (from July 2014 to January 2015) about the HSR system which covers many aspects of the system, criticisms of it, and responses to those criticisms.

- The Bold Bets: California on the Move? conference was hosted February 2015 by The Atlantic magazine and Siemens. There were some significant discussions, presentations, and interviews. Notably, Dan Richard, chair of the Authority, was interviewed by James Fallows. (This interview is online.)[51]

References

- ↑ California High-Speed Rail Authority. "Implementation Plan" (PDF). pp. 23, 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Project Vision and Scope". California High-Speed Rail Authority. 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ↑ "ES.0 Executive Summary : ES.1 SUPPLEMENTAL ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS REPORT RESULTS" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Authority - State of California". Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Sheehan, Tim (April 2, 2012). "California revamps high-speed rail business plan". The Fresno Bee.

- 1 2 "Project Update Report to the California State Legislature" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Staff (February 21, 2015). "The most expensive public-works project in U.S. history". The Week.

- ↑ "2012 Business Plan | Business Plans | California High-Speed Rail Authority". Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "Statewide Rail Modernization | Programs | California High-Speed Rail Authority". Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "Appendix L. Conceptual Cost Estimates" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "2014 Business Plan Ridership and Revenue Technical Memorandum" (PDF).

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Authority - State of California" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ Michael Cabanatuan (November 15, 2007). "High Speed Rail Authority staff advises Pacheco Pass route to L.A.". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ↑ "State Picks Pacheco Pass For High-Speed Rail". CBS 13. Associated Press. February 9, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ↑ This segment runs through the Chowchilla Wye. Merced to Fresno

- ↑ "High-Speed Rail Authority approves Fresno-Bakersfield section | abc30.com". Abclocal.go.com. 2014-05-07. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Weikel, Dan (August 12, 2014). "Central Valley bullet train construction gets federal go-ahead". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Bakersfield to Palmdale Project Section". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "California HSR Authority releases study". Railway Age. January 10, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ "High-Speed Rail from Bakersfield to Palmdale - Story". Kerngoldenempire.com. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- 1 2 "Connecting California : 2014 Business Plan" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph (December 13, 2014). "Bullet train's eventual link to L.A. rail system far from clear-cut". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Edelhart, Courtenay; Cox, John (23 May 2011). "Revisiting of rail route angers cities". Californian (Bakersfield, California). Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sun Valley Beautiful" (PDF). High Speed Rail. State of California. January 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph (30 June 2014). "Burbank-Palmdale segment added to bullet train timetable". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ "Palmdale to Burbank Section 2014 Scoping Report" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph (January 23, 2016). "Bullet train project: Southern California segment might be built last, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ Posted: April 28, 2015 2:00 a.m. (2015-04-28). "UPDATE: SCV residents give loud and clear message against high-speed rail". Signalscv.com. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "Residents express concerns over high-speed rail through Angeles National Forest". abc7.com. 2015-01-14. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "PALMDALE TO BURBANK PROJECT SECTION UPDATE" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "Burbank to Los Angeles Section 2014 SCOPING REPORT" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- 1 2 "Los Angeles to Anaheim Project Section". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ MAKINEN, JULIE (Sep 17, 2015). "A high-speed rail from L.A. to Las Vegas? China says it's partnering with U.S. to build". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Blog » HSR Trainset Bids Could Create New Domestic Industry". Cahsrblog.com. 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Respaut, Robin (2015-05-21). "China may have edge in race to build California's bullet train - Yahoo News". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Sheehan, Tim (December 27, 2014). "In California’s high-speed train efforts, worldwide manufacturers jockey for position". The Fresno Bee.

- ↑ "AFT SCHEDULE 1PART A: AUTHORITY TIER III TRAINSETS PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATION" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Robert (October 7, 2014). "Caltrain and CHSRA To Work Together for Level Boarding". California High Speed Rail Blog.

- ↑ Boone, Andrew (May 19, 2015). "Design of High-Speed Trains Threatens to Diminish Caltrain Capacity". Streetsblog San Francisco.

- 1 2 California High-Speed Rail Authority (December 14, 2009). "December 2009 Business Plan Report to the Legislature" (PDF). pp. 109–110. Retrieved June 24, 2011

- ↑ Druce, Paul (June 6, 2011). "High speed rail operational surplus". Reason & Rail. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ↑ Yarow, Jay. "Amtrak Loses $32 Per Passenger". Business Insider.

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Authority - State of California" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Environmental Report : October 2013" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ BY JULIET WILLIAMS The Associated Press (2013-06-14). "Key green light for California high-speed rail - The Bakersfield Californian". Bakersfield.com. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Blog » HSR: A Pathway Out of Poverty". Cahsrblog.com. 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Blog » The End of the Beginning". Cahsrblog.com. 2015-01-06. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "California High-Speed Rail and the Central Valley Economy : January 2015" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "High-speed rail and infill: A great marriage for California". sacbee. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- 1 2 Official website: California High Speed Rail Peer Review Group

- 1 2 3 4 "Bold Bets: California on the Move?". The Atlantic. February 25, 2015.

Video of event

- ↑ "Making the Most of High-Speed Rail in California: Lessons from France and Germany". gmfus.org. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Promoting Intermodal Connectivity at California’s High-Speed Rail Stations" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "The California High Speed Rail Proposal: A Due Diligence Report" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- 1 2 "An Updated Due Diligence Report" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- 1 2 Fallows, James (July 11, 2014). "California High-Speed Rail—the Critics' Case". The Atlantic.

- 1 2 "Comparison of Providing the Equivalent Capacity to High-Speed Rail through Other Modes" (PDF). April 2012. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

After adjusting the analysis to be more comparable to the costs described in the Business Plan, the total costs of equivalent investment in airports and highways would be $123-138 billion (in 2011 dollars) to build 4,295-4652 lane-miles of highways, 115 gates, and four runways for Phase 1 Blended and Phase 1 Full Build, respectively... In year-of-expenditure (YOE) dollars, the highway and airport costs would be $158-186 billion.

- ↑ Vance, Ashlee (12 August 2013). "Revealed: Elon Musk Explains the Hyperloop, the Solar-Powered High-Speed Future of Inter-City Transportation". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Musk, Elon (August 12, 2013). "Hyperloop Alpha" (PDF). SpaceX. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Musk announces plans to build Hyperloop demonstrator". Gizmag.com. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

[Musk] will develop and construct a Hyperloop demonstrator.

- ↑ "Experts Raise Doubts Over Elon Musk's Hyperloop Dream". MIT Technology Review. 2013-08-12. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ↑ "Revised 2012 Business Plan" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ PRESS RELEASE (July 10, 2014). "Cost of High Speed Rail in China One Third Lower than in Other Countries". The World Bank.

- ↑ "High-Speed Rail Is at a Critical Juncture". California Legislative Analyst's Office.

- ↑ Buchanan, Wyatt (January 4, 2012). "High-speed rail shouldn't be funded, report says". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 4, 2012

- ↑ Judy Lin (July 6, 2012). "California High Speed Rail Funding Approved". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ↑ Tolmach, Richard F. (August 2012). "High Speed Bait and Switch: $8 billion bill to produce zero miles of HSR". California Rail News 24 (2) (Sacramento, CA: TRAC). p. 1.

- ↑ Fallows, James (December 13, 2014). "That Winning Bid for California's High-Speed Rail: Is It Suspiciously Low?". The Atlantic.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Robert (April 13, 2015). "CHSRA Selects Tutor Perini-Zachry-Parsons Bid for Central Valley Section". California High Speed Rail Blog.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph; Weikel, Dan (May 10, 2015). "Doing the math on California's bullet train fares". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Final Report: Independent Peer Review of the California High-Speed Rail Ridership and Revenue Forecasting Process" (PDF). August 1, 2011.

We are satisfied with the documentation presented in Cambridge Systematics, and conclude that it demonstrates that the model produces results that are reasonable and within expected ranges for the current environmental planning and Business Plan applications of the model. We were very pleased with the content, quality and quantity of the information.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Robert (May 10, 2015). "LA Times Completely Botches Story on HSR Fares". California High Speed Rail Blog. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Robert (13 May 2015). "Amtrak Crash Puts Spotlight on Rail Infrastructure Needs". California High Speed Rail Blog.

- ↑ "California High-Speed Rail Ridership and Revenue Model Version 2.0 Model Documentation" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "California High-Speed Rail 2014 Business Plan" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "World's longest high-speed train to decelerate a bit". People's Daily Online. 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Dan Walters (December 15, 2011). "Legal trap could snare bullet train". North County Times. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ↑ "TEN THINGS YOU DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT CALIFORNIA HIGH-SPEED RAIL (OUT OF THOUSANDS OF THINGS ALMOST NO ONE KNOWS)". Citizens for California High Speed Rail Accountability (CCHSRA). April 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Enviro Groups Rally Against Fast-Tracking California High-Speed Rail". The Heartland Institute. July 16, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Setback for HSR in San Jose to San Francisco Environmental Analysis". Planetizen. November 13, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Altamont". TRANSDEF. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Property rights battles threaten to further slow California's costly, long awaited bullet train project". FoxNews. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph (14 March 2015). "Ready to fight: Some growers unwilling to lose land for bullet train". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Sheehan, Tim (23 August 2014). "Land deals slowing California high-speed rail plan". The Fresno Bee. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph (24 February 2015). "Critics fear bullet train will bring urban sprawl to Central Valley". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ Vartabedian, Ralph (May 30, 2015). "San Fernando leaders confront state officials over bullet train route". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "California High Speed Rail Blog » Eminent Domain Process Gears Up". California High Speed Rail Blog. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Robert (March 7, 2015). "Tutor Perini May Demand Compensation for HSR Delays". California High Speed Rail Blog. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Sheehan, Tim (June 16, 2015). "Heavy equipment finally moving on California high-speed rail construction". The Fresno Bee.

- ↑ Sheehan, Tim (July 13, 2015). "More properties eyed in Valley counties for high-speed rail". The Fresno Bee.

- ↑ "SB 1420 Senate Bill - CHAPTERED". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "California Proposition 1A, High-Speed Rail Act (2008)". ballotpedia.org. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: High Speed Intercity Passenger Rail Program: California" (Press release). The Whitehouse. January 27, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ↑ "California High-Speed Rail Awarded $715 Million" (Press release). California High-Speed Rail Authority. October 28, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of Transportation Redirects $1.195 Billion in High-Speed Rail Funds" (Press release). U.S. Department of Transportation. December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "U.S. Transportation Secretary LaHood Announces $2 Billion for High-Speed Intercity Rail Projects to Grow Jobs, Boost U.S. Manufacturing and Transform Travel in America" (Press release). U.S. Department of Transportation. May 9, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ↑ Michael Martinez (July 19, 2012). "Governor signs law to make California home to nation's first truly high-speed rail". CNN. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Office of Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. - Newsroom". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Cap-and-Trade Revenue: Likely Much Higher Than Governor's Budget Assumes". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Capitol Alert". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "HSR 15-02 Request for Expressions of Interest for Delivery of an Initial Operating Segment" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- ↑ "Trial date set in Prop. 1A lawsuit over high-speed train plans". fresnobee. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Judge limits evidence for Kings County suit over high-speed rail". fresnobee. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ↑ Sheehan, Tim (June 2, 2015). "Farm Bureaus jump into Supreme Court high-speed rail case". The Fresno Bee.

- ↑ "High-Speed Rail Authority Approves State Matching Funds to Extend Backbone of Statewide System" (Press release). California High-Speed Rail Authority. December 20, 2010. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ↑ "High-Speed Rail Authority Hosts Official Groundbreaking Ceremony" (PDF). California High-Speed Rail Authority. January 6, 2015.

- ↑ "High-Speed Rail Authority Selects HNTB to Oversee Next Phase of Construction in the Central Valley" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to California High-Speed Rail. |

- California High-Speed Rail Authority – official website

- California State Rail Plan (2013) – official document

- AB 3034 – official document (the authorizing legislation for Proposition 1A)

- San Jose Mercury News coverage

- Huffington Post coverage

- Progressive Railroading coverage

- The Fresno Bee coverage

- California High Speed Rail Blog – proponent

- Against California HSR – opponent

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||