California Proposition 209

| Elections in California | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Proposition 209 (also known as the California Civil Rights Initiative or CCRI) is a California ballot proposition which, upon approval in November 1996, amended the state constitution to prohibit state governmental institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity, specifically in the areas of public employment, public contracting, and public education. Modeled on the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the California Civil Rights Initiative was authored by two California academics, Glynn Custred and Tom Wood. It was the first electoral test of affirmative action policies in America.

History

The political campaign to place the language of CCRI on the California ballot as a constitutional amendment was initiated by Joe Gelman (president of the Board of Civil Service Commissioners of the City of Los Angeles), Arnold Steinberg (a pollster and political strategist) and Larry Arnn (president of the Claremont Institute). It was later endorsed by Governor Pete Wilson and supported and funded by the California Civil Rights Initiative Campaign, led by University of California Regent Ward Connerly, a Wilson ally. A key co-chair of the campaign was law professor Gail Heriot, who served as a member of the United States Commission on Civil Rights. The initiative was opposed by affirmative action advocates and traditional civil rights and feminist organizations on the left side of the political spectrum. Proposition 209 was voted into law on November 5, 1996, with 54 percent of the vote, and has withstood legal scrutiny ever since.

In November 2006, a similar amendment modeled on California's Proposition 209 was passed in Michigan, titled the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative. The constitutionality of the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative was challenged in the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals. The case made its way to the United States Supreme Court. On April 22, 2014, the US Supreme Court ruled 6-2 that the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative is constitutional, and that states had the right to ban the practice of racial and gender preferences/affirmative action if they chose to do so through the electoral process.

On December 3, 2012, California State Senator Edward Hernandez introduced California Senate Constitutional Amendment No.5 (SCA-5) in the State Senate.[1] This initiative proposed an amendment to the state constitution to remove provisions of California Proposition 209 related to public post-secondary education, to permit state universities to consider applicants' race, gender, color, ethnicity, or national origin in admission decisions. SCA-5 was passed by the California State Senate on January 30, 2014.[2] However, following resistance from various citizen groups, including Asian American groups, Senator Hernandez withdrew his measure from consideration.[3]

Legal challenges

On November 27, 1996, U.S. District Court Judge Thelton Henderson blocked enforcement of the proposition. A three-judge panel of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals subsequently overturned that ruling. Proposition 209 has been the subject of many lawsuits in state courts since its passage but has vigorously withstood legal scrutiny over the years, in every instance.

On August 2, 2010, the Supreme Court of California found for the second time that Proposition 209 was constitutional.[4][5] The ruling, by a 6-1 majority, followed a unanimous affirmation in 2000 of the constitutionality of Prop. 209 by the same court.[6][7]

On April 2, 2012, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the latest challenge to Proposition 209. The three-judge panel concluded that it was bound by a 9th Circuit ruling in 1997 upholding the constitutionality of the affirmative action ban. Ninth Circuit Judge A. Wallace Tashima disagreed in part with the ruling, saying he believes the court "wrongly decided" the issue in 1997.[8]

Effect on enrollment and graduation rates

Since the passage of Proposition 209, higher graduation rates have been posted at University of California schools,[9] which led opponents of affirmative action to suggest a causal link between Proposition 209 and a better-prepared student body. The African American graduation rate at the University of California, Berkeley increased by 6.5 percent,[10] and rose even more dramatically, from 26 percent to 52 percent, at the University of California, San Diego.[9]

While African American graduation rates at UC Berkeley increased by 6.5 percent,[10] the enrollment rates dropped significantly.[11] Criticism was made of the fact that of the 4,422 students in UCLA's freshman class of 2006, only 100 (2.26%) were African American.[12]

Based on "University of California Applicants, Admits and New Enrollees by Campus, Race/Ethnicity", prepared by Institutional Research, the University of California Office of the President, August 11, 2011, enrollment percentages of the four major ethnic groups university-wide are:

| Ethnic group | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 4.3 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Asian American | 37.1 | 35.2 | 36.1 | 36.4 | 35.3 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 38.1 | 38.6 | 37.9 | 40.0 | 40.1 | 41.3 | 40.8 | 38.8 | 39.9 | 39.8 |

| Chicano/Latino | 15.2 | 15.1 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.9 | 14.2 | 14.7 | 15.5 | 16.7 | 18.1 | 19.2 | 20.7 |

| White | 36.2 | 37.4 | 38.4 | 40.2 | 33.8 | 37.8 | 36.7 | 35.9 | 35.7 | 34.9 | 33.8 | 33.9 | 31.9 | 31.3 | 30.6 | 29.7 | 26.8 |

Chicano/Latino enrollment percentage, after several years of decreases, dramatically increased from the lowest 11.3% in 1998 to 20.7% in 2010. In contrast, White enrollment percentage, after achieving a high of 40.2% in 1997, decreased significantly to 26.8% in 2010. Asian American enrollment percentage remained stable.

The acceptance rate, or yield rate, is about the number of students who accepted their admission offer. Asian American acceptance rates are much higher than other ethnic groups.[13]

Text

The text of Proposition 209 was drafted by Cal State anthropology professor Glynn Custred and California Association of Scholars Executive Director Thomas Wood. Its passage amended the California constitution to include a new section (Section 31 of Article I), which now reads:

(a) The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.

(b) This section shall apply only to action taken after the section's effective date.

(c) Nothing in this section shall be interpreted as prohibiting bona fide qualifications based on sex which are reasonably necessary to the normal operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.

(d) Nothing in this section shall be interpreted as invalidating any court order or consent decree which is in force as of the effective date of this section.

(e) Nothing in this section shall be interpreted as prohibiting action which must be taken to establish or maintain eligibility for any federal program, where ineligibility would result in a loss of federal funds to the state.

(f) For the purposes of this section, "state" shall include, but not necessarily be limited to, the state itself, any city, county, city and county, public university system, including the University of California, community college district, school district, special district, or any other political subdivision or governmental instrumentality of or within the state.

(g) The remedies available for violations of this section shall be the same, regardless of the injured party's race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin, as are otherwise available for violations of then-existing California antidiscrimination law.

(h) This section shall be self-executing. If any part or parts of this section are found to be in conflict with federal law or the United States Constitution, the section shall be implemented to the maximum extent that federal law and the United States Constitution permit. Any provision held invalid shall be severable from the remaining portions of this section.[14]

Support

Supporters of Proposition 209 contended that existing affirmative action programs led public employers and universities to reject applicants based on their race, and that Proposition 209 would "restore and reconfirm the historic intention of the 1964 Civil Rights Act."[15] The basic and simple premise of Proposition 209 is that every individual has a right, and that right is not to be discriminated against, or granted a preference, based on their race or gender. Since the number of available positions are limited, discriminating against or giving unearned preference to a person based solely, or even partially on race or gender deprives qualified applicants of all races an equal opportunity to succeed. It also pits one group against another and perpetuates social tension.

- Organizations in support

- American Civil Rights Institute

- Pacific Legal Foundation

- Center for Equal Opportunity

Opposition

Opponents of Proposition 209 argued that it would end affirmative action practices of tutoring, mentoring, outreach and recruitment of women and minorities in California universities and businesses.[16] Immediately after passage of Proposition 209, students held demonstrations and walk-outs in protest at several universities including UC Berkeley, UCLA, UC Santa Cruz, and San Francisco State University.[17] Organizations that oppose Proposition 209 and similar measures claim that women and people of color are unfairly hampered by an educational system which has given preference to white males for centuries, and that affirmative action has proven a successful way of countering the preferential selection of white males.

On September 1, 2011, SB 185 passed both chambers of the California State Legislature, but was vetoed by Governor Jerry Brown. SB 185 would have countered Proposition 209 and authorized the University of California and the California State University to consider race, gender, ethnicity, and national origin, along with other relevant factors, in undergraduate and graduate admissions, to the maximum extent permitted by the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, Section 31 of Article I of the California Constitution, and relevant case law. SB 185 was strongly supported by the University of California Students Association.

In August 2013, the California State Senate passed California Senate Constitutional Amendment No. 5, which would have effectively repealed Proposition 209. However, before the bill could be put on a referendum ballot, following high opposition from the Asian-American community, the bill was shelved.

On February 24, 2014, Gene D. Block, chancellor of UCLA, sent an open letter to all students and faculty expressing his strong opposition to Proposition 209.[18]

- Organizations in opposition

- ACLU of Southern California

- Feminist Majority

- By Any Means Necessary (BAMN)

- California Votes NO! on 209

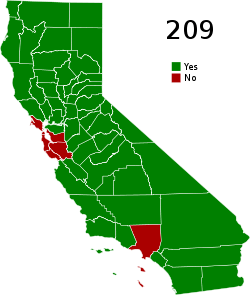

Results

| Proposition 209 | ||

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| |

5,268,462 | 54.55 |

| No | 4,388,733 | 45.45 |

| Valid votes | 9,657,195 | 94.11 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 604,444 | 5.89 |

| Total votes | 10,261,639 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters and turnout | 15,662,075 | 65.53 |

| Source: November 5, 1996, General Election Statement of Vote | ||

Private sector response

One response to Proposition 209 was the establishment of the IDEAL Scholars Fund to provide community and financial support for underrepresented students at the University of California, Berkeley. Private universities and colleges, as well as employers, are not subject to Proposition 209.

See also

- Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

- Grutter v. Bollinger

- Gratz v. Bollinger

- Senate Constitutional Amendment No.5

References

- ↑ "Senate Constitutional Amendment No. 5 (May 30, 2013)".

- ↑ "Senate Vote on SCA 5 (Jan 30, 2014)".

- ↑ "John A. Pérez halts effort to overturn California's Prop. 209". Sacramento Bee. March 17, 2014.

- ↑ Coral Construction, Inc., v. City and County of San Francisco, S152934 (August 2, 2010)

- ↑ Mintz, Howard (August 2, 2010). "California Supreme Court upholds Prop. 209 affirmative action ban". San Jose Mercury News.

- ↑ See Hi-Voltage Wire Works v. City of San Jose, 24 Cal.4th 537 (2000).

- ↑ Mintz, Howard. "California Supreme Court upholds Prop. 209 affirmative action ban". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ Mintz, Howard (April 2, 2012). "California affirmative action ban challenge rejected". San Jose Mercury News.

- 1 2 Grad Rates increased at UC schools

- 1 2 Eryn Hadley (2005), “Did the Sky Really Fall? Ten Years after California's Proposition 209,” BYU Journal of Public Law 20:103, pp. 129-130.

- ↑ "Universities Record Drop In Black Admissions". washingtonpost.com. 2004-11-22. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ↑ "Daily Bruin". Dailybruin.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ↑ Institutional Research, the University of California Office of the President (August 11, 2012). "University of California Applicants, Admits and New Enrollees by Campus, Race/Ethnicity" (PDF). University of California.

- ↑ Text of Proposition 209

- ↑ Argument in Favor of Proposition 209

- ↑ Rebuttal to Argument in Favor of Proposition 209

- ↑ "Students Protest Proposition 209". United Press International, November 7, 1996.

- ↑ The Impact of Proposition 209 and Our Duty to Our Students

Scholarship and commentary

- Heriot, Gail (2001). University of California Admissions under Proposition 209: Unheralded Gains Face an Uncertain Future, NEXUS: A Journal of Opinion 6:163.

- Jamison, Cynthia C. (2004). The Cost of Defiance: Plaintiffs’ Entitlement to Damages Under the California Civil Rights Initiative, Southwestern Univ. Law Review 33:521.

- McCutcheon, Stephen R., Jr., & Travis J. Lindsey (2004). The Last Refuge of Official Discrimination: The Federal Funding Exception to California’s Proposition 209, 44 Santa Clara Law Review 457.

- Myers, Caitlin Knowles (2007). A Cure for Discrimination? Affirmative Action and the Case of California's Proposition 209, Industrial & Labor Relations Review 60:379.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||