Calico, San Bernardino County, California

| Calico | |

|---|---|

| Ghost town, former mining town | |

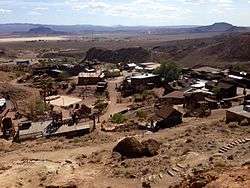

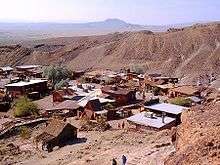

|

Calico in the Mojave Desert | |

Calico Location within the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 34°56′56″N 116°51′51″W / 34.94889°N 116.86417°WCoordinates: 34°56′56″N 116°51′51″W / 34.94889°N 116.86417°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Bernardino |

| Elevation[1] | 2,283 ft (696 m) |

| Time zone | Pacific (UTC−8) |

| • Summer (DST) | PDT (UTC−7) |

| ZIP code | 92398 |

| Area codes | 442/760 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1660414[2] |

| Website |

cms |

| Reference no. | 782 |

Calico is a ghost town and former mining town in San Bernardino County, California, United States. Located in the Calico Mountains of the Mojave Desert region of Southern California, it was founded in 1881 as a silver mining town, and today has been converted into a county park named Calico Ghost Town. Located off Interstate 15, it lies 3 miles (4.8 km) from Barstow and 3 miles from Yermo. Giant letters spelling CALICO can be seen on the Calico Peaks behind the ghost town from the freeway. Walter Knott purchased Calico in the 1950s, architecturally restoring all but the five remaining original buildings to look as they did in the 1880s. Calico received California Historical Landmark #782,[3] and in 2005 was proclaimed by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to be California's Silver Rush Ghost Town.[4]

History

In 1881 four prospectors were leaving Grapevine Station (present day Barstow, California) for a mountain peak to the northeast. Describing the peak as "calico-colored", the peak, the mountain range to which it belonged, and the town that followed were all called Calico.[5] The four prospectors discovered silver in the mountain, and opened the Silver King Mine, which was California's largest silver producer in the mid-1880s.[5] A post office was established in early 1882, and the Calico Print, a weekly newspaper, started publishing. The town soon supported three hotels, five general stores, a meat market, bars, brothels, and three restaurants and boarding houses. The county established a school district and a voting precinct.[6] The town also had a deputy sheriff and two constables, two lawyers and a justice of the peace, five commissioners, and two doctors. There was also a Wells Fargo office and a telephone and telegraph service.[5] At its height of silver production during 1883 and 1885,[6] Calico had over 500 mines and a population of 1,200 people.[5] Local badmen were buried in the Boot Hill cemetery.[7][8]

The discovery of the borate mineral colemanite in the Calico mountains a few years after the settlement of the town also helped Calico's fortunes, and in 1890 the estimated population of the town was 3,500, with nationals of China, England, Ireland, Greece, France, and the Netherlands, as well as Americans living there.[9] In the same year, the Silver Purchase Act was enacted, and it drove down the price of silver.[5] By 1896, its value had decreased to $0.57 per troy ounce, and Calico's silver mines were no longer economically viable.[5] The post office was discontinued in 1898,[10] and the school closed not long after.[6] By the turn of the century, Calico was all but a ghost town,[9] and with the end of borax mining in the region in 1907 the town was completely abandoned. Many of the original buildings were moved to Barstow, Daggett and Yermo.[9]

An attempt to revive the town was made in about 1915, when a cyanide plant was built to recover silver from the unprocessed Silver King Mine's deposits. Walter Knott and his wife Cordelia, founders of Knott's Berry Farm, were homesteaded at Newberry Springs around this time, and Knott helped build the redwood cyanide tanks for the plant.[9][11] In 1951, Knott purchased the town and began restoring it to its original condition referencing old photographs. He installed a longtime employee named "Calico Fred" Noller as resident caretaker and official greeter.[12] In 1966, Knott donated the town to San Bernardino County, and Calico became a County Regional Park.[13]

In 2012 Calico became the first ghost town in America to be re-opened for residential purposes. 100m from the ghost town site, six luxury villas were built with a trading value of $4.5 million.

Current status

Calico has been restored to the look of the silver rush era when it flourished, although many original buildings were removed and replaced instead with gingerbread architecture and false facades that tourists would expect to see in a Western-themed town;[14] Most of the restored and newly built buildings are made of wood with a simple, rustic architecture and a severely weathered appearance. Some structures still stand dating back to the town's operational years: Lil's Saloon; the town office; the former home of Lucy Lane, which is now the main museum but was originally the town's post office and courthouse; Smitty's Gallery; the general store; and Joe's Saloon. There is also a replica of the schoolhouse on the site of the original building.[14] The one-time homes of the town's Chinese citizens exist as ruins only; nothing remains of the former "family" residential area on a nearby bluff.[15]

In November 1962, Calico Ghost Town was registered as a California Historical Landmark (Landmark #782),[3] In 2002, Calico vied with Bodie in Mono County to be recognized as the Official State Ghost Town. In 2005, a compromise was finally reached when the State Senate and State Assembly agreed to list Bodie as the Official State Gold Rush Ghost Town and Calico the Official State Silver Rush Ghost Town.[16]

Today, the park operates mine tours, gunfight stunt shows, gold panning, several restaurants, the historic, 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) narrow gauge Calico & Odessa Railroad, and a number of trinket stores. It is open every day except Christmas, and requires an entrance fee. Additional fees are required for some attractions. Overnight camping is also available. Special events are held throughout the year including a Spring Festival in May, Calico Days in early October, and a Ghost Town haunt in late October.[17]

The Calico Cemetery, which holds between 96 and 130 graves, has had burials in the 20th and 21st centuries.[18][19][20][21]

Image gallery

In popular culture

- The town was the basis for the Kenny Rogers and the First Edition album The Ballad of Calico.

- On their 2009 album Gutter Anthems Celtic Fusion band Enter the Haggis has a song about the ghost town called "Ghosts of Calico".

- Children's author Susan Lendroth wrote a picture book, Calico Dorsey, Mail Dog of the Mining Camps, based on the true story of a dog that carried mail between Calico and East Calico in 1885.

- Calico was the location for the final scenes of the film The Prowler (1951) starring Van Heflin and Evelyn Keyes.

- Gorillaz shot the music video for "Stylo" in Calico.

- Calico is mentioned in "Swansea", a song by Joanna Newsom.

- Calico is the basis of the buried town in the Call of Duty: Black Ops II DLC map, Resolution 1295.

- Calico is the setting for the 1965 episode "The Book" of the syndicated television series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Ronald W. Reagan. In the story line, Tom Skerritt as young gambler Patrick Hogan, who wins a small fortune at the roulette table in a Calico saloon, with the help of a Chinese friend, Wong Lee (George Takei). The two soon meet separate but speedy demises.[22]

- Tamara Thorne's 2004 horror novel Thunder Road was inspired by Calico.[23]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calico Ghost Town. |

References

- ↑ "Calico". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Calico, California". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- 1 2 "Calico". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ↑ http://cms.sbcounty.gov/parks/Parks/CalicoGhostTown.aspx

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Varney, Philip (1990). Southern California's Best Ghost Towns. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-8061-2252-8.

- 1 2 3 Hensher, Alan (1991). Ghost Towns of the Mojave Desert. California Classic Books. pp. 18–21. ISBN 1-879395-07-X.

- ↑ http://www.interment.net/column/feature/boothill-graveyards/boot-hill-graveyards-of-the-old-west.htm

- ↑ Garner, John W. (February 1941). "Calico Cemetery". The Desert Magazine 5 (40).

- 1 2 3 4 Varney (1990), p. 52

- ↑ Durham, David L. (1998). "Part Eleven – Southeast Region (Imperial, Riverside and San Bernardino Counties)". California's Geographic Names. Clovis, California: Word Dancer Press. p. 1401. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ↑ Kooiman, Helen (1973). Walter Knott: Keeper of the Flame. Fullerton, California: Plycon Press. pp. 153–58.

- ↑ "Long dead silver town returns to life", Toledo Blade, May 13, 1951

- ↑ Varney (1990), pp. 52–53

- 1 2 Varney (1990), p. 53

- ↑ Recorded narration on the Calico and Odessa Railroad ride

- ↑ Harvey, Steve (August 3, 2005). "Only in LA; Wild West Ghost Town's Image in California Gains Bit of Polish". The Los Angeles Times (Tribune Publishing Company). p. B.4. ISSN 0458-3035.

- ↑ "Calico Ghost Town". San Bernardino County Regional Parks. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ↑ Peyton, Paige M. (2012). "Ch. 3, Nobody Home: The Deserted Decades". Images of America: Calico. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7385-8905-3.

- ↑ Steeples, Douglas W. (1999). Treasure from the Painted Hills: A History of Calico, California, 1882–1907. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-313-30836-5.

- ↑ Calico Cemetery at FindaGrave

- ↑ Orawczyk, Sarah (January 3, 2012). "An unusual funeral: Calico characters find final resting place in town's graveyard". Desert Dispatch.

- ↑ "The Book". Internet Movie Data Base. October 28, 1965. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ Weeks, John (21 August 2009). "The news out of Calico Ghost Town is dispiriting". San Bernardino Sun. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

External links

- Official website

- Information about Calico and the surrounding mines from Digital-Desert.com

- History of Calico from MousePlanet.com

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||