Caledonian Canal

| Caledonian | |

|---|---|

|

Swing bridge over the Caledonian Canal | |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat length | 150 ft 0 in (45.72 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 35 ft 0 in (10.7 m) |

| Locks | 29 |

| Status | Navigable |

| Navigation authority | Scottish Canals |

| History | |

| Original owner | Caledonian Canal Commissioners |

| Principal engineer | Thomas Telford |

| Date of act | 1803 |

| Date completed | 1822 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Inverness |

| End point | Fort William |

Caledonian Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Caledonian Canal connects the Scottish east coast at Inverness with the west coast at Corpach near Fort William in Scotland. The canal was constructed in the early nineteenth century by Scottish engineer Thomas Telford, and is a sister canal of the Göta Canal in Sweden, also constructed by Telford.

Route

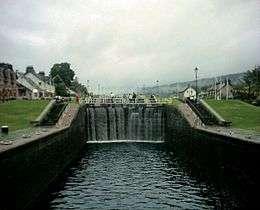

The canal runs some 60 miles (97 km) from northeast to southwest. Only one third of the entire length is man-made, the rest being formed by Loch Dochfour, Loch Ness, Loch Oich, and Loch Lochy.[1] These lochs are located in the Great Glen, on a geological fault in the Earth's crust. There are 29 locks (including eight at Neptune's Staircase, Banavie), four aqueducts and 10 bridges in the course of the canal.

History

The canal was conceived as a way of providing much-needed employment to the Highland region. The area was depressed as a result of the Highland Clearances, which had deprived many of their homes and jobs. Laws had been introduced which sought to eradicate the local culture, including bans on wearing tartan, playing the bagpipes, and speaking Gaelic. Many emigrated to Canada or elsewhere, or moved to the Scottish Lowlands.[2] The canal would also provide a safer passage for wooden sailing ships from the north east of Scotland to the south west, avoiding the route around the north coast via Cape Wrath and the Pentland Firth.[3]

The first survey for a canal was carried out by James Watt in 1773, but it was the Caledonian Canal Commission that paved the way for the actual construction.[2] On 27 July 1803, an Act of Parliament was passed to authorise the project,[4] and the canal engineer Thomas Telford was asked to survey, design and build the waterway. Telford worked with William Jessop on the survey, and the two men oversaw the construction until Jessop died in 1814.[3] The canal was expected to take seven years to complete, and to cost £474,000, to be funded by the Government, but both estimates were inadequate.[2]

Because of the remoteness of the location, construction was started at both ends, so that completed sections could be used to bring in the materials for the middle sections. At Corpach, near Fort William, the entrance lock was built on rock, but at the other end, there was 56 feet (17 m) of mud below the proposed site of the sea lock. Rock was tipped on top of the mud and was allowed to settle for six months before construction could begin. The ground through which the canal was cut was variable, and further difficulties were experienced with the construction of the locks, the largest ever built at the time. There were also problems with the labour force, with high levels of absence, particularly during and after the potato harvest and the peat cutting season. This led to Telford bringing in Irish navvies to manage the shortfall, which led to further criticism, since one of the main aims of the project was to reduce unemployment in the Highlands.[2] The canal finally opened in 1822, having taken an extra 12 years to complete, and cost £910,000. Over 3,000 local people had been employed in its construction,[5] but the draught had been reduced from 20 feet (6.1 m) to 15 feet (4.6 m), in an effort to save costs. In the meantime, shipbuilding had advanced, with the introduction of steam-powered iron-hulled ships, many of which were now too big to use the canal. The Royal Navy did not need to use the canal either, as Napoleon had been defeated at Waterloo in 1815, and the perceived threat to shipping when the canal was started was now gone.[2]

Operation

Before long, defects in some of the materials used became apparent, and part of Corpach double lock collapsed in 1843. This led to a decision to close the canal to allow repairs to be carried out, and the depth was increased to 18 feet (5.5 m) at the same time.[2] The work was designed by Telford's associate James Walker, and completed by 1847,[3] but not all of the traffic expected to return to using the canal did so. Commercially, the venture was not a success, but the dramatic scenery through which it passes led to it becoming a tourist attraction. Queen Victoria took a trip along it in 1873, and the publicity surrounding the trip resulted in a large increase in visitors to the region and the canal. The arrival of the railways at Fort William, Fort Augustus and Inverness did little to harm the canal, as trains were scheduled to connect with steamboat services.[2]

There was an upsurge in commercial traffic during the First World War when components for the construction of mines were shipped through the canal on their way to Inverness from America, and fishing boats used it to avoid the route around the north of Scotland. Ownership passed to the Ministry of Transport in 1920, and then to British Waterways in 1962. Improvements were made, with the locks being mechanised between 1964 and 1969. By 1990, the canal was in obvious need of restoration, with lock walls bulging, and it was estimated that repairs would cost £60 million. With no prospect of the Government funding this, British Waterways devised a repair plan, and between 1995 and 2005, sections of the canal were drained each winter. Stainless steel rods were used to tie the double-skinned lock walls together, and over 25,000 tonnes of grout were injected into the lock structures. All of the lock gates were replaced, and the result was a canal whose structures are probably in a better condition than they have ever been.[2]

The canal is now a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and attracts over half a million visitors each year. British Waterways, who work with the Highland Council and the Scottish Forestry Commission through the Great Glen Ways Initiative, were hoping to increase this number to over 1 million by 2012.[2] There are many ways for tourists to enjoy the canal, such as taking part in the Great Glen Rally, cycling along the tow-paths, or cruising on Hotel Barges.

Names

The canal has several names in Scottish Gaelic including Amar-Uisge/Seòlaid a' Ghlinne Mhòir ("Waterway of the Great Glen"), Sligh'-Uisge na h-Alba ("Waterway of Scotland") and a literal translation (An) Canàl Cailleannach.

| Locks along the Caledonian Canal | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clachnaharry Sea Lock, Inverness | 57°29′26″N 4°15′46″W / 57.4906°N 4.2628°W | NH644467 | |

| Muirtown Locks, Inverness | 57°28′51″N 4°14′56″W / 57.4807°N 4.2490°W | NH652456 | |

| Dolgarroch Lock | 57°25′59″N 4°18′08″W / 57.4330°N 4.3023°W | NH618404 | |

| Entrance to Lock Ness | 57°24′28″N 4°19′43″W / 57.4077°N 4.3285°W | NH602376 | |

| Fort Augustus Locks | 57°08′41″N 4°40′59″W / 57.1447°N 4.6831°W | NH377091 | |

| Kytra Lock | 57°07′21″N 4°43′22″W / 57.1224°N 4.7229°W | NH352067 | |

| Cullochy Lock | 57°05′52″N 4°44′23″W / 57.0979°N 4.7397°W | NH341041 | |

| Laggan Locks | 57°01′33″N 4°49′31″W / 57.0259°N 4.8254°W | NN286963 | |

| Gairlochy Top Lock | 56°54′53″N 4°59′38″W / 56.9146°N 4.9940°W | NN178843 | |

| Neptune's Staircase, Banavie | 56°50′47″N 5°05′37″W / 56.8465°N 5.0935°W | NN114770 | |

| Corpach Locks | 56°50′31″N 5°07′23″W / 56.8420°N 5.1231°W | NN096766 |

.jpg)

References

Bibliography

- Cameron, A. D. (2005). The Caledonian Canal. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-403-7.

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2009). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (8th Ed.). Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-1-84623-010-3.

- Hadfield, Charles; Skempton, A. W. (1979). William Jessop, Engineer. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7603-9.

- Hayward, David (2007). The Caledonian Canal. British Waterways. ISBN 978-0-9556339-2-8.

- Hutton, Guthrie (n.d.). Getting to know... The Caledonian Canal. privately published.

- Hutton, Guthrie (1998). The Caledonian Canal: Lochs, Lochs and Pleasure Steamers. Ochiltree: Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 1-84033-033-3.

- Lindsay, Jean (1968). The Canals of Scotland. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4240-1.

- McKnight, Hugh (1981). The Shell Book of Inland Waterways. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8239-4.

- Priestley, Joseph (1831). "Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and Railways of Great Britain".

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caledonian Canal. |

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caledonian Canal. |

- Caledonian Canal at scottishcanals.co.uk

- Information on the great glen canoe trail

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1937), "The Caledonian Canal", Shipping Wonders of the World, pp. 631–633 illustrated description of the Caledonian Canal

Coordinates: 57°06′45″N 4°44′19″W / 57.112478°N 4.738541°W