Death by burning

Deliberately causing death through the effects of combustion, or effects of exposure to extreme heat, has a long history as a form of capital punishment. Many societies have employed it as an execution method for activities considered criminal such as treason, rebellious actions by slaves, heresy, witchcraft and demonstrated sexual transgressions, such as incest or homosexuality. The best known type of executions of death by burning is when the condemned is bound to a large wooden stake. This is usually called burning at the stake (or, in some cases, auto-da-fé). But other forms of death resulting from exposure to extreme heat are known, not only by exposure to flames or burning materials. For example, pouring substances, such as molten metal, onto a person (or down their throat or into their ears) are attested, as well as enclosing persons within, or attaching them to, metal contraptions subsequently heated. Immersion in a heated liquid as a form of execution is reviewed in death by boiling.

Cause of death

For burnings at the stake, if the fire was large (for instance, when a number of prisoners were executed at the same time), death often came from carbon monoxide poisoning before flames actually caused harm to the body. If the fire was small, however, the convict would burn for some time until death from hypovolemia (the loss of blood and/or fluids, since extensive burns often require large amounts of intravenous fluid, because the subsequent inflammatory response causes significant capillary fluid leakage and edema), heatstroke and/or simply the thermal decomposition of vital body parts.[1]

Historical usage

Antiquity

Ancient Near East

Old Babylonia

The 18th century BC law code promulgated by Babylonian king Hammurabi specifies several crimes in which death by burning was thought appropriate. Looters of houses on fire could be cast into the flames, and priestesses who abandoned cloisters and began frequenting inns and taverns could be punished by being burnt alive. Furthermore, a man who began committing incest with his mother after the death of his father could be ordered by courts to be burned alive.[2]

Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, several incidents of burning alive perceived rebels are attested. For example, Senusret I (r. 1971–1926 BC) is said to have rounded up the rebels in campaign, and burnt them as human torches. Under the civil war flaring under Takelot II more than a thousand years later, the Crown Prince Osorkon showed no mercy, and burned several rebels alive.[3] On the statute books, at least, women committing adultery might be burned to death. Jon Manchip White, however, did not think capital judicial punishments were often carried out, pointing to the fact that the pharaoh had to ratify personally each verdict.[4] Furthermore, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BC) asserts that the Egyptians had a particularly terrible punishment for children who murdered their parents: With sharpened reeds, bits of flesh of the size of a finger were cut from the criminal's body. Then he was placed on a bed of thorns and burnt alive.[5]

Assyria

In the Middle Assyrian period, paragraph 40 in a preserved law text concerns the obligatory unveiled face for the professional prostitute, and the concomitant punishment if she violated that by veiling herself (the way wives were to dress in public):

A prostitute shall not be veiled. Whoever sees a veiled prostitute shall seize her ... and bring her to the palace entrance. ... they shall pour hot pitch over her head.[6]

For the Neo-Assyrians, mass executions seem to have been not only designed to instill terror and to enforce obedience, but also as proof of their might. For example, Neo-Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (r.883-859 BC) was evidently proud enough of his bloody work that he committed it to monument and eternal memory as follows:[7]

I cut off their hands, I burned them with fire, a pile of the living men and of heads over against the city gate I set up, men I impaled on stakes, the city I destroyed and devastated, I turned it into mounds and ruin heaps, the young men and the maidens in the fire I burned.

Hebraic tradition

In Genesis 38, Judah orders Tamar – the widow of his son, living in his household – to be burned when she is believed to have become pregnant by an extramarital sexual relation. Tamar saves herself by proving that Judah is himself the father of her child. In the Book of Jubilees, the same story is basically told, with some intriguing differences, according to Caryn A. Reeder. In Genesis, Judah is exercising his patriarchal power at a distance, whereas he and the relatives seem more actively involved in Tamar's impending execution.[8]

In Hebraic law, death by burning was prescribed for 10 different forms of sexual crimes: The imputed crime of Tamar, namely that a married daughter of a priest commits adultery, and 9 versions of relationships considered as incestuous, such as having sex with one's own daughter, or granddaughter, but also, for example, to have sex with one's mother-in-law or with one's wife's daughter.[9]

In the Mishnah, the following manner of burning the criminal is described:

The obligatory procedure for execution by burning: They immersed him in dung up to his knees, rolled a rough cloth into a soft one and wound it about his neck. One pulled it one way, one the other until he opened his mouth. Thereupon one ignites the (lead) wick and throws it in his mouth, and it descends to his bowels and sears his bowels.

That is, the person dies from being fed molten lead.[10] The Mishnah is, however, a fairly late collections of laws, from about the 3rd century AD, and scholars believe it replaced the actual punishment of burning in the old biblical texts.[11]

Ancient Rome

In the 6th century AD collection of the sayings and rulings of the pre-eminent jurists from earlier ages, the Digest, a number of crimes are regarded as punishable by death by burning. The 3rd century jurist Ulpian, for example, says that enemies of the state, and deserters to the enemy are to be burned alive. His rough contemporary, the juristical writer Callistratus mentions that arsonists are typically burnt, as well as slaves who have conspired against the well-being of their masters (this last also, on occasion, being meted out to free persons of "low rank").[12] The punishment of burning alive arsonists (and traitors) seems to have been particularly ancient; it was included in the Twelve Tables, a mid-5th BC law code, that is, about 700 years prior to the times of Ulpian and Callistratus.[13] According to ancient reports, Roman authorities executed many of the early Christian martyrs by burning. An example of this is the earliest chronicle of a martyrdom, that of Polycarp.[14] Sometimes this was by means of the tunica molesta,[15] a flammable tunic:[16]

... the Christian, stripped naked, was forced to put on a garment called the tunica molesta, made of papyrus, smeared on both sides with wax, and was then fastened to a high pole, from the top of which they continued to pour down burning pitch and lard, a spike fastened under the chin preventing the excruciated victim from turning the head to either side, so as to escape the liquid fire, until the whole body, and every part of it, was literally clad and cased in flame.

In AD 326, Constantine the Great promulgated a law that increased the penalties for parentally non-sanctioned "abduction" of their girls, and concomitant sexual intercourse/rape. The man would be burnt alive without the possibility of appeal, and the girl would receive the same treatment if she had participated willingly. Nurses who had corrupted their female wards and led them to sexual encounters would have molten lead poured down their throats.[17] In the same year, Constantine also passed a law that said if a woman married her own slave, both would be subjected to capital punishment, the slave by burning.[18] In AD 390, Emperor Theodosius issued an edict against male prostitutes and brothels offering such services; those found guilty should be burned alive.[19]

Ritual child sacrifice in Carthage

Beginning in the early 3rd century BC, Greek and Roman writers have commented on the purported institutionalized child sacrifice the North African Carthaginians are said to have performed in honour of the gods Baal Hammon and Tanit. The earliest writer, Cleitarchus is among the most explicit. He says live infants were placed in the arms of a bronze statue, the statue's hands over a brazier, so that the infant slowly rolled into the fire. As it did so, the limbs of the infant contracted and the face was distorted into a sort of laughing grimace, hence called "the act of laughing". Other, later authors such as Diodorus Siculus and Plutarch says the throats of the infants were generally cut, before they were placed in the statue's embrace[20] In the vicinity of ancient Carthage, large scale grave yards containing the incinerated remains of infants, typically up to the age of 3, have been found; such graves are called "tophets". However, some scholars have argued that these findings are not evidence of systematic child sacrifice, and that estimated figures of ancient natural infant mortality (with cremation afterwards and reverent separate burial) might be the real historical basis behind the hostile reporting from non-Carthaginians. A late charge of the imputed sacrifice is found by the North African bishop Tertullian, who says that child sacrifices were still carried out, in secret, in the countryside at his time, 3rd century AD.[21]

Celtic traditions

According to Julius Caesar, the ancient Celts practiced the burning alive of humans in a number of settings. For example, in Book 6, chapter 16, he writes of the Druidic sacrifice of criminals within huge wicker frames shaped as men:

Others have figures of vast size, the limbs of which formed of osiers they fill with living men, which being set on fire, the men perish enveloped in the flames. They consider that the oblation of such as have been taken in theft, or in robbery, or any other offence, is more acceptable to the immortal gods; but when a supply of that class is wanting, they have recourse to the oblation of even the innocent.

Slightly later, in Book 6, chapter 19, Caesar also says the Celts perform, on the occasion of death of great men, the funeral sacrifice on the pyre of living slaves and dependants ascertained to have been "beloved by them". Earlier on, in Book 1, chapter 4, he relates of the conspiracy of the nobleman Orgetorix, charged by the Celts for having planned a coup d'état, for which the customary penalty would be burning to death. It is said Orgetorix committed suicide to avoid that fate[22]

Human sacrifice around the Eastern Baltic

Throughout the 12th–14th centuries, a number of non-Christian peoples living around the Eastern Baltic Sea, such as Old Prussians and Lithuanians were charged by Christian writers with performing human sacrifice. For example, Pope Gregory IX issued a papal bull denouncing an alleged practice among the Prussians, that girls were dressed in fresh flowers and wreaths and were then burned alive as offerings to evil spirits.[23]

Christian States

Byzantium

Under 6th century emperor Justinian I, the death penalty had been decreed for impenitent Manicheans, but a specific punishment was not made explicit. By the 7th century, however, those found guilty of "dualist heresy" could risk being burned at the stake.[24] Those found guilty of performing magical rites, and corrupting sacred objects in the process, might face death by burning, as evidenced in a 7th-century case.[25] In the 10th century AD, the Byzantines instituted death by burning for parricides, i.e. those who had killed their own relatives, replacing the older punishment of poena cullei, the stuffing of the convict in a leather sack along with a rooster, a viper, a dog and a monkey, and then throwing the sack into the sea.[26]

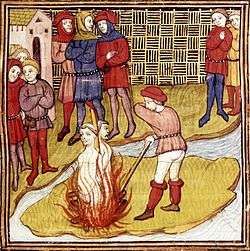

Medieval Inquisition and the burning of heretics

Civil authorities burned persons judged to be heretics under the medieval Inquisition. William Graham Sumner says burning heretics had become customary practice in the latter half of the twelfth century in continental Europe, and that death by burning became statutory punishment from the beginning 13th century. Sumner notes that death by burning for heretics was made positive law by Pedro II of Aragon in 1197. In 1224 Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, made burning a legal alternative, and in 1238, it became the principal punishment in the Empire. In Sicily, the punishment was made law in 1231, whereas in France, Louis IX made it binding law in 1270.[27]

As England in the fifteenth century grew weary of the teachings of John Wycliffe and the Lollards, kings, priests, and parliaments reacted with fire. In 1401, Parliament passed the De heretico comburendo act, which can be loosely translated as "Regarding the burning of heretics." Lollard persecution would continue for over a hundred years in England. The Fire and Faggot Parliament met in May 1414 at Grey Friars Priory in Leicester to lay out the notorious Suppression of Heresy Act 1414, enabling the burning of heretics by making the crime enforceable by the Justices of the peace. John Oldcastle, a prominent Lollard leader, was not saved from the gallows by his old friend King Henry V. Oldcastle was hanged and his gallows burned in 1417. Jan Hus was burned at the stake after being accused at the Roman Catholic Council of Constance (1414–18) of heresy. The ecumenical council also decreed that the remains of John Wycliffe, dead for 30 years, should be exhumed and burned. (This posthumous execution was carried out in 1428.)

Burnings of Jews

Several incidents are recorded of massacres on Jews from the 12th through 16th centuries in which they were burned alive, often on account of the blood libel. In 1171 in Blois, for example, 51 Jews were burned alive (the entire adult community). In 1191, King Philip Augustus ordered around 100 Jews burnt alive.[28] That Jews purportedly performed host desecration also led to mass burnings; In 1243 in Beelitz, the entire Jewish community was burnt alive, and in 1510 in Berlin, some 26 Jews were burnt alive for the same crime.[29] During the "Black Death" in the mid-14th century a spate of large-scale massacres occurred. One libel was that the Jews had poisoned the wells. In 1349, as panic grew along with the increasing death toll from the plague, general massacres, but also specifically mass burnings, began to occur. Six hundred (600) Jews were burnt alive in Basel alone. A large mass burning occurred in Strasbourg, where no fewer than 2000 Jews were burnt alive in what became known as the Strasbourg massacre.[30]

A Jewish male, Johannes Pfefferkorn, met a particularly gruesome death in 1514 in Halle. He had been charged with a number of crimes, such as having impersonated a priest for twenty years, performed host desecration, stolen Christian children to be tortured and killed by other Jews, poisoning 13 people and poisoning wells. He was lashed to a pillar in such a way that he could run about it. Then, a ring of glowing coal was made around him, a fiery ring that was gradually pushed ever closer to him, until he was roasted to death.[31]

The Lepers' Plot of 1321

Not only Jews could be victims of mass hysteria on charges like that of poisoning wells. This particular charge, well-poisoning, was the basis for a large scale hunt of lepers in 1321 France. In the spring of 1321, in Périgueux, people became convinced that the local lepers had poisoned the wells, causing ill-health among the normal populace. The lepers were rounded up and burned alive. The action against the lepers didn't stay local, though, but had repercussions throughout France, not least because King Philip V issued an order to arrest all lepers, those found guilty to be burnt alive. Jews became tangentially included as well; at Chinon alone, 160 Jews were burnt alive.[32] All in all, around 5000 lepers and Jews are recorded in one tradition to have been killed during the Lepers' Plot hysteria.[33]

The charge of the lepers' plot was not wholly confined to France; existent records from England show that on Jersey the same year, at least one family of lepers were burnt alive for having poisoned others.[34]

Spanish Inquisition against Moriscos and Marranos

The Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478, with the aim of preserving Catholic orthodoxy; some of its principal targets were formally converted Jews, called "Marranos" thought relapsing into Judaism, or the Moriscos, formally converted Muslims thought to have relapsed into Islam. The public executions of the Spanish Inquisition were called autos-da-fé; convicts were "released" (handed over) to secular authorities in order to be burnt.

Estimates of how many were executed on behest of the Spanish Inquisition have been offered from early on; historian Hernando del Pulgar (1436 – c. 1492) estimated that 2,000 people were burned at the stake between 1478 and 1490.[35] Estimates range from 30,000 to 50,000 burnt at the stake (alive or not) at the behest of the Spanish Inquisition during its 300 years of activity have previously been given and are still to be found in popular books.[36]

In February 1481, in what is said to be the first auto-da-fé, six Marranos were burnt alive in Seville. In November 1481, 298 Marranos were burnt publicly at the same place, their property confiscated by the Church.[37] Not all Maranos executed by being burnt at the stake seem to have been burnt alive. If the Jew "confessed his heresy", the Church would show mercy, and he would be strangled prior to the burning. Autos-da-fé against Maranos extended beyond the Spanish heartland. In Sicily, in 1511–15, 79 were burnt at the stake, while from 1511 to 1560, 441 Maranos were condemned to be burned alive.[38] In Spanish American colonies, autos-da-fé were held as well. For example, in 1664, a man and his wife were burned alive in Río de la Plata, and in 1699, a Jew was burnt alive in Mexico City.[39]

In 1535, five Moriscos were burned at the stake on Majorca, the images of a further four were also burnt in effigy, since the actual individuals had managed to flee. During the 1540s, some 232 Moriscos were paraded in autos-da-fé in Zaragoza; five of those were burnt at the stake.[40] For the local Inquisition in Granada, some 917 Moriscos appeared before the tribunal in 1550–95, 20 were burnt at the stake.[41] Forty-five (45) Moriscos are said to have been burned for heresy in 1728.[42]

Portuguese Inquisition at Goa

In 1560, the Portuguese Inquisition opened offices in the Indian colony Goa, known as Goa Inquisition. Its aim was to protect Catholic orthodoxy among new converts to Christianity, and retain hold on the old, particularly against "Judaizing" deviancy. From the seventeenth century, Europeans were shocked at the tales of how brutal and extensive the activities of the Inquisition were. What modern scholars have established, is that some 4,046 individuals in the time 1560–1773 received some sort of punishment from the Portuguese Inquisition, whereof 121 persons were condemned to be burned alive, of those 57 who actually suffered that fate, while the rest escaped it, and were burnt in effigy, instead.[43] For the Portuguese Inquisition in total, not just at Goa, modern estimates of persons actually executed on its behest is about 1,200, whether burnt alive or not.[44]

Legislation concerning "crimes against nature"

From the 12th to the 18th centuries, various European authorities legislated (and held judicial proceedings) against sexual crimes such as sodomy or bestiality; often, the prescribed punishment was that of death by burning. Many scholars think that the first time death by burning appeared within explicit codes of law for the crime of sodomy was at the ecclesiastical 1120 Council of Nablus in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Here, if public repentance were done, the death penalty might be avoided.[45] In Spain, the earliest records for executions for the crime of sodomy are from the 13th–14th centuries, and it is noted there that the preferred mode of execution was death by burning.[46] At Geneva, the first recorded burning of sodomites occurred in 1555, and up to 1678, some two dozen met the same fate. In Venice, the first burning took place in 1492, and a monk was burnt as late as in 1771.[47] The last case in France where two men were condemned by court to be burned alive for engaging in consensual homosexual sex was in 1750 (although, it seems, they were actually strangled prior to being burned). The last case in France where a man was condemned to be burned for a murderous rape of a boy occurred in 1784.[48]

Crackdowns and the public burning of a couple of homosexuals might lead to local panic, and persons thus inclined fleeing from the place. The traveller William Lithgow witnessed such a dynamic when he visited Malta in 1616 :

The fifth day of my staying here, I saw a Spanish soldier and a Maltezen boy burnt in ashes, for the public profession of sodomy; and long before night, there were above an hundred bardassoes, whorish boys, that fled away to Sicily in a galliot, for fear of fire; but never one bugeron stirred, being few or none there free of it.[49]

The actual punishment meted out to, for example, pederasts could differ according to status. While both in 1532 and 1409 Augsburg two men were burned alive for their offenses, a rather different procedure was meted out to four clerics in the 1409 case guilty of the same offence: Instead of being burnt alive, they were locked into a wooden casket that was hung up in the Perlachturm and they starved to death in that manner.[50]

The 1532 penal code of Charles V

In 1532, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V promulgated his penal code Constitutio Criminalis Carolina. A number of crimes were punishable with death by burning, such as coin forgery, arson, and sexual acts "contrary to nature".[51] Also, those guilty of aggravated theft of sacred objects from a church could be condemned to be burnt alive.[52] Only those found guilty of malevolent witchcraft[53] could be punished by death by fire.[54]

The last burnings from 1804 and 1813

According to the jurist Eduard Osenbrüggen, the last case he knew of where a person had been judicially burned alive on account of arson in Germany happened in 1804, in Hötzelsroda, close by Eisenach.[55] The manner in which Johannes Thomas[56] was executed is described as following, 13 July that year. Some feet above the actual pyre, attached to a stake, a wooden chamber had been constructed, into which the delinquent was placed. Pipes or chimneys, filled with sulphuric material led up to the chamber, and that was first lit, so that Thomas died from inhaling the sulphuric smoke, rather than being strictly burnt alive, before his body was consumed by the general fire. Some 20,000 people had gathered to watch Thomas' execution.[57]

Although Thomas is regarded as the last to have been actually executed by means of fire (in this case, through suffocation), the couple Johann Christoph Peter Horst and his lover Friederike Louise Christiane Delitz, who had made a career of robberies in the confusion made by their acts of arson, were condemned to be burnt alive in Berlin 28 May 1813. They were, however, according to Gustav Radbruch, secretly strangled just prior to being burnt, namely when their arms and legs were tied fast to the stake.[58]

Although these two cases are the last where the execution by burning might be said to have being carried out in some degree, Eduard Osenbrüggen mentions that verdicts to be burned alive were given in several cases for different German states afterwards, such as in cases from 1814, 1821, 1823, 1829 and finally in a case from 1835.[59]

Witch Hunts

Burning was used by Christians during the witch-hunts of Europe. The penal code known as the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) decreed that sorcery throughout the Holy Roman Empire should be treated as a criminal offence, and if it purported to inflict injury upon any person the witch was to be burnt at the stake. In 1572, Augustus, Elector of Saxony imposed the penalty of burning for witchcraft of every kind, including simple fortunetelling.[60] From the latter half of the 18th century, the number of "9 million witches burned in Europe" has been bandied about in popular accounts/media, but has never had a following among specialist researchers.[61] Today, based on meticulous study of trial records, ecclesiastical and inquisitorial registers and so on, as well as on the utilization of modern statistical methods, the specialist research community on witchcraft has reached an agreement for roughly 40,000–50,000 people executed for witchcraft in Europe in total,[62] and by no means all of them executed by being burned alive. Furthermore, it is solidly established that the peak period of witch-hunts was the century 1550–1650, with a slow increase preceding it, from the 15th century onwards, as well a sharp drop postceding it, with "witch hunts" having basically fizzled out by the first half of the 18th century.[63]

Famous Cases

Notable individuals executed by burning include Jacques de Molay (1314),[64] Jan Hus (1415),[65] Joan of Arc (1431),[66] Girolamo Savonarola (1498),[67] Patrick Hamilton (1528),[68] John Frith (1533),[69] William Tyndale (1536), Michael Servetus (1553),[70] Giordano Bruno (1600),[71] Urbain Grandier (1634),[72] and Avvakum (1682).[73] Anglican martyrs John Rogers,[74] Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were burned at the stake in 1555.[75] Thomas Cranmer followed the next year (1556).[76]

Denmark

In Denmark, after the 1536 reformation, Christian IV of Denmark (r.1588–1648) encouraged the practice of burning witches, in particular by the law against witchcraft in 1617. In Jutland, the mainland part of Denmark, more than half the recorded cases of witchcraft in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries occurred after 1617. Rough estimates says about a thousand persons were executed due to convictions for witchcraft in the 1500–1600s, but it is not wholly clear if all of the transgressors were burned to death.[77]

Great Britain

Mary I ordered hundreds of religious dissenters (Protestants) burnt at the stake during her reign (1553–58) in what would be known as the "Marian Persecutions".[78] Many of the heretics killed by Mary are listed in Actes and Monuments, written by Foxe in 1563 and 1570. Edward Wightman, a Baptist from Burton on Trent, was the last person burned at the stake for heresy in England in Lichfield, Staffordshire on 11 April 1612.[79] Although cases can be found of burning heretics in the 16th and 17th centuries England, that penalty for heretics was historically relatively new. For example, it did not exist in 14th century England, and when the bishops in England petitioned king Richard II to institute death by burning for heretics in 1397, the king flatly refused, and no one was burnt for heresy during his reign.[80] Just one year after the death of Richard II, however, in 1401, William Sawtrey was burnt alive for heresy.[81] Death by burning for heresy was formally abolished by King Charles II in 1676.[82]

The traditional punishment for women found guilty of treason was to be burned at the stake, where they did not need to be publicly displayed naked, whereas men were hanged, drawn and quartered. The jurist William Blackstone argued as follows for the differential punishment of females vs. males:

For as the decency due to sex forbids the exposing and public mangling of their bodies, their sentence (which is to the full as terrible to sensation as the other) is to be drawn to the gallows and there be burned alive[83]

However, as described in Camille Naish's "Death Comes to the Maiden", in practice, the woman's shift would burn away at the beginning, and she would be left naked anyway. There were two types of treason, high treason for crimes against the Sovereign, and petty treason for the murder of one's lawful superior, including that of a husband by his wife. Commenting on the 18th century execution practice, Frank McLynn says that most convicts condemned to burning were not burnt alive, and that the executioners made sure the women were dead before consigning them to the flames.[84]

The last to have been condemned to death for "petty treason" was Mary Bailey, whose body was burned in 1784. The last woman to be convicted for "high treason", and have her body burnt, in this case for the crime of coin forgery, was Catherine Murphy in 1789.[85] The last case where a woman was actually burnt alive in Great Britain is that of Catherine Hayes in 1726, for the murder of her husband. In this case, one account says this happened because the executioner accidentally set fire to the pyre before he had hanged Hayes properly.[86] The historian Rictor Norton has assembled a number of contemporary newspaper reports on the actual death of Mrs. Hayes, internally somewhat divergent. The following excerpt is one example:

The fuel being placed round her, and lighted with a torch, she begg’d for the sake of Jesus, to be strangled first: whereupon the Executioner drew tight the halter, but the flame coming to his hand in the space of a second, he let it go, when she gave three dreadful shrieks; but the flames taking her on all sides, she was heard no more; and the Executioner throwing a piece of timber into the Fire, it broke her skull, when her brains came plentifully out; and in about an hour more she was entirely reduced to ashes.[87]

Scotland

James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) shared the Danish king's interest in witch trials. This special interest of the king resulted in the North Berwick witch trials, which led more than seventy people to be accused of witchcraft in Scotland due to inclement weather. James sailed in 1590 to Denmark to meet his betrothed, Anne of Denmark, who, ironically, is believed by some to have secretly converted to Roman Catholicism herself from Lutheranism around 1598, although historians are divided on whether she ever was received into the Roman Catholic faith.[88]

The last to be executed as a witch in Scotland was Janet Horne in 1727, condemned to death for using her own daughter as a flying horse to travel with. Janet Horne was burnt alive in a tar barrel.[89]

Ireland

Petronilla de Meath (c. 1300–1324) was the maidservant of Dame Alice Kyteler, a fourteenth-century Hiberno-Norman noblewoman. After the death of Kyteler's fourth husband, the widow was accused of practicing witchcraft and Petronilla of being her accomplice. Petronilla was tortured and forced to proclaim that she and Kyteler were guilty of witchcraft. Petronilla was then flogged and eventually burnt at the stake on 3 November 1324, in Kilkenny, Ireland.[90][91] Hers was the first known case in the history of the British Isles of death by fire for the crime of heresy. Kyteler was charged by the Bishop of Ossory, Richard de Ledrede, with a wide slate of crimes, from sorcery and demonism to the murders of several husbands. She was accused of having illegally acquired her wealth through witchcraft, which accusations came principally from her stepchildren, the children of her late husbands by their previous marriages. The trial predated any formal witchcraft statute in Ireland, thus relying on ecclasiastical law (which treated witchcraft as heresy) rather than English common law (which treated it as a felony). Under torture, Petronilla claimed she and her mistress applied a magical ointment to a wooden beam, which enabled both women to fly. She was then forced to proclaim publicly that Lady Alice and her followers were guilty of witchcraft.[90] Some were convicted and whipped, but others, Petronilla included, were burnt at the stake. With the help of relatives, Alice Kyteler fled, taking with her Petronilla's daughter, Basilia.[92]

In 1895, Bridget Cleary (née Boland), a County Tipperary woman, was burnt by her husband and others, the stated motive for the crime being the belief that the real Bridget had been abducted by fairies with a changeling left in her place. Her husband claimed to have slain only the changeling. The gruesome nature of the case prompted extensive press coverage. The trial was closely followed by newspapers in both Ireland and Britain.[93] As one reviewer commented, nobody, with the possible exception of the presiding judge, thought it was an ordinary murder case.[93]

Slavery and Colonialism in the Americas

North America

Indigenous North Americans often used burning as a form of execution, against members of other tribes or white settlers during the 18th and 19th centuries. Roasting over a slow fire was a customary method.[94] {See Captives in American Indian Wars}.

In Massachusetts, there are two known cases of burning at the stake. First, in 1681, a slave named Maria tried to kill her owner by setting his house on fire. She was convicted of arson and burned at the stake in Roxbury.[95] Concurrently, a slave named Jack, convicted in a separate arson case, was hanged at a nearby gallows, and after death his body was thrown into the fire with that of Maria. Second, in 1755, a group of slaves had conspired and killed their owner, with servants Mark and Phillis executed for his murder. Mark was hanged and his body gibbeted, and Phillis burned at the stake, at Cambridge.[96]

In New York, several burnings at the stake are recorded, particularly following suspected slave revolt plots. In 1708, one woman was burnt and one man hanged. In the aftermath of the New York Slave Revolt of 1712, 20 people were burnt (one of the leaders slowly roasted, before he died after 10 hours of torture[97]) and during the alleged slave conspiracy of 1741, at least 13 slaves were burnt at the stake.[98]

Bartolomé de las Casas, a 16th-century eyewitness to the brutal subjugation of the Native Americans by the Spanish conquistadores, has left a particularly harrowing description of how roasting alive was a favoured technique of repression:[99]

They usually dealt with the chieftains and nobles in the following way: they made a grid of rods which they placed on forked sticks, then lashed the victims to the grid and lighted a smoldering fire underneath, so that little by little, as those captives screamed in despair and torment, their souls would leave them. I once saw this, when there were four or five nobles lashed on grids and burning; I seem even to recall that there were two or three pairs where others were burning, and because they uttered such loud screams that they disturbed the captain's sleep, he ordered them to be strangled. And the constable, who was worse than an executioner, did not want to obey that order (and I know the name of that constable and know his relatives in Seville), but instead put a stick over the victims' tongues, so they could not make a sound, and he stirred up the fire, but not too much, so that they roasted slowly, as he liked.

The last known burning by the Spanish Colonial government in Latin America was of Mariana de Castro, in Lima, Peru in February 1732.[100]

British West Indies

In 1760, the slave rebellion known as Tacky's War broke out in Jamaica. Apparently, some of the defeated rebels were burned alive, while others were gibbeted alive, left to die of thirst and starvation.[101]

In 1774, 9 African slaves at Tobago were found complicit of murdering a white man. Eight of them had first their right arms chopped off, and were then burned alive bound to stakes, according to the report of an eyewitness.[102]

Dutch Suriname

In 1855 the Dutch abolitionist and historian Julien Wolbers spoke to the Anti Slavery Society in Amsterdam. Painting a dark picture of the condition of slaves in Suriname, he mentions in particular that as late as in 1853, just two years previously, "three Negroes were burnt alive".[103]

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence in the 1820s contained several instances of death by burning, and historian William St. Clair offers several examples in his That Greece Might Still Be Free. For example, when the Greeks in April 1821 captured a corvette near Hydra, the Greeks chose to roast to death the 57 Turkish crew members. After the fall of Tripolitsa in September 1821, European officers were horrified to note that not only were Turks suspected of hiding money being slowly roasted after having had their arms and legs cut off but, in one instance, three Turkish children were roasted over a fire while their parents were forced to watch. On their part, the Turks committed many similar acts; for example, in retaliation they gathered up Greeks in Constantinople, throwing several of them into huge ovens, baking them to death.[104]

Islamic countries

A rival prophet to Muhammad

The Arab chieftain Tulayha ibn Khuwaylid ibn Nawfal al-Asad set himself up as a rival prophet to Muhammad in AD 630, and after Muhammad's death in 632, Tulayah had a strong following which was, however, soon quashed in the so-called Ridda Wars. He himself escaped, though, and later was reconverted to Islam, but many of his rebel followers were burnt to death, his own mother choosing to embrace the same fate.[105]

Catholic monks in 13th century Tunis and Morocco

A number of monks are said to have been burnt alive in Tunis and Morocco in the 13th century. In 1243, two English monks, Brothers Rodulph and Berengarius, after having secured the release of some 60 captives, were charged with being English spies, and were burnt alive on 9 September. In 1262, Brothers Patrick and William, again having freed captives, but also sought to proselytize among Muslims, were burnt alive in Morocco. In 1271, some 11 Catholic monks were burnt alive in Tunis. Several other cases are reported.[106]

Converts to Christianity

Apostasy, i.e. the act of converting to another religion, was (and remains so in a few countries) punishable with death.

The French traveller Jean de Thevenot, traveling the East in the 1650s, says: "Those that turn Christians, they burn alive, hanging a bag of Powder about their neck, and putting a pitched Cap upon their Head."[107] Travelling the same regions some 60 years earlier, Fynes Moryson writes:

A Turke forsaking his Fayth and a Christian speaking or doing anything against the law of Mahomett are burnt with fyer.[108]

(NOTE: De Thevenot says Christians committing blasphemy against Islam were impaled, rather than burnt, if they do not convert to Islam.)

Muslim heretics

Certain accursed ones of no significance is the term used by Taş Köprü Zade in the Şakaiki Numaniye to describe some members of the Hurufiyya who became intimate with the Sultan Mehmed II to the extent of initiating him as a follower. This alarmed members of the Ulema, particularly Mahmut Paşa, who then consulted Mevlana Fahreddin. Fahreddin hid in the Sultan's palace and heard the Hurufis propound their doctrines. Considering these heretical, he reviled them with curses. The Hurufis fled to the Sultan, but Fahreddin's denunciation of them was so virulent that Mehmed II was unable to defend them. Farhreddin then took them in front of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, Edirne, where he publicly condemned them to death. While preparing the fire for their execution, Fahreddin accidentally set fire to his beard. However the Hurufis were burnt to death.

Barbary States, 18th century

John Braithwaite, staying in Morocco in the late 1720s, says that apostates from Islam would be burnt alive:

THOSE that can be proved after Circumcision to have revolted, are stripped quite naked, then anointed with Tallow, and with a Chain about the Body, brought to the Place of Execution, where they are burnt.

Similarly, he notes that non-Muslims entering mosques or being blasphemous against Islam will be burnt, unless they convert to Islam.[109] The chaplain for the English in Algiers at the same time, Thomas Shaw, wrote that whenever capital crimes were committed either by Christian slaves or Jews, the Christian or Jew was to be burnt alive.[110] Some generations later in, in Morocco in 1772, a Jewish interpreter to the British, and a merchant in his own right, sought from the Emperor of Morocco restitution for some goods confiscated, and was burnt alive for his impertinence. His widow made her woes clear in a letter to the British.[111]

In 1792 in Ifrane, Morocco, 50 Jews preferred to be burned alive, rather than convert to Islam.[112] In Algiers 1794, the Jewish rabbi Mordecai Narboni was accused of having maligned Islam in a quarrel with his neighbour. He was ordered to be burnt alive unless he converted to Islam, but he refused and was therefore executed the 16th Tammuz, year 5554, according to Hebrew calendar (14 July 1794)[113]

In 1793, Ali Benghul made a short-lived coup d'état in Tripoli, deposing the ruling Karamanli dynasty. During his short, violent reign he seized for example, the two interpreters for the Dutch and English consuls, both of them Jews, and roasted them over a slow fire, on charges of conspiracy and espionage.[114]

Persia

During a famine in Persia in 1668, the government took severe measures against those trying to profiteer from the misfortune of the populace. Restaurant owners found guilty of profiteering were slowly roasted on spits, and greedy bakers were baked in their own ovens.[115]

A physician, Dr C.J. Wills, traveling through Persia in 1866–81 noted that shortly before his (Wills') arrival, a "priest" had been burned alive. Wills wrote:[116]

Just prior to my first arrival in Persia, the "Hissam-u-Sultaneh", another uncle of the king, had burned a priest to death for a horrible crime and murder; the priest was chained to a stake, and the matting from the mosques piled on him to a great height, the pile of mats was lighted and burnt freely, but when the mats were consumed the priest was found groaning, but still alive. The executioner went to Hissam-u-Sultaneh who ordered him to obtain more mats, pour naphta on them, and apply a light, which 'after some hours' he did.

Roasting by means of heated metal

The previous cases concern primarily death by burning through contact with open fire or burning material; a slightly different principle is to enclose an individual within, or attach him to, a metal contraption which is subsequently heated. In the following, some reports of such incidents, or anecdotes about such are included.

The brazen bull

Perhaps the most infamous example of a brazen bull, which is a hollow metal structure shaped like a bull within which the condemned is put, and then roasted alive as the metal bull is gradually heated up, is the one allegedly constructed by Perillos of Athens for the 6th century BC tyrant Phalaris at Agrigentum, Sicily. As the story goes, the first victim of the bull was its constructor Perillos himself.[117] The story of a brazen bull as an execution device is not wholly unique. About 1000 years later, for example, in AD 497, it can be read in an old chronicle about the Visigoths on the Iberian Peninsula and the south of France:

Burdunellus became a tyrant in Spain[118] ... handed over by his own men and having been sent to Toulouse, he was placed inside a bronze bull and burnt to death.[119]

Fate of a Scottish regicide

Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl was a Scottish nobleman complicit in the murder of king James I of Scotland. On 26 March 1437 Stewart had a red hot iron crown placed upon his head, was cut in pieces alive, his heart was taken out, and then thrown in a fire. A papal nuncio, the later Pope Pius II witnessed the execution of Stewart and his associate Sir Robert Graham, and, reportedly, said he was at a loss to determine whether the crime committed by the regicides, or the punishment of them was the greatest.[120]

György Dózsa on the iron throne

György Dózsa led a peasant's revolt in Hungary, and was captured in 1514. He was bound to a glowing iron throne and a likewise hot iron crown was placed on his head, and he was roasted to death.[121]

The tale of the murderous midwife

In a few English 18th and 19th century newspapers and magazines, a tale was circulated about the particularly brutal manner a French midwife was put to death by 28 May 1673 in Paris. No less than 62 infant skeletons were found buried on her premises, so she was condemned on multiple accounts of abortion/infanticide. One detailed account of her supposed execution runs as follows:

A gibbet was erected, under which a fire was made, and the prisoner being brought to the place of execution, was hung up in a large iron cage, in which were also placed sixteen wild cats, which had been catched in the woods for the purpose.—When the heat of the fire became too great to be endured with patience, the cats flew upon the woman, as the cause of the intense pain they felt.—In about fifteen minutes they had pulled out her intrails, though she continued yet alive, and sensible, imploring, as the greatest favour, an immediate death from the hands of some charitable spectator. No one however dared to afford her the least assistance; and she continued in this wretched situation for the space of thirty-five minutes, and then expired in unspeakable torture. At the time of her death, twelve of the cats were expired, and the other four were all dead in less than two minutes afterwards.

The English commentator adds his own view on the matter as follows:"However cruel this execution may appear with regard to the poor animals, it certainly cannot be thought too severe a punishment for such a monster of iniquity, as could calmly proceed in acquiring a fortune by the deliberate murder of such numbers of unoffending, harmless innocents. And if a method of executing murderers, in a manner somewhat similar to this was adapted in England, perhaps the horrid crime of murder might not so frequently disgrace the annals of the present times."[122] The English story is derived from a pamphlet published in 1673.[123]

Pouring molten metal down the throat or ears

Molten gold poured down the throat

A number of stories concern individuals who are said to have been executed by having molten gold poured down their throats. For example, in 88 BC, Mithridates VI of Pontus captured the Roman general Manius Aquillius, and executed him by pouring molten gold down his throat.[124] A popular but unsubstantiated rumor also had the Parthians executing the famously greedy Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus in this manner in 53 BC [125]

Genghis Khan is said to have poured molten gold down the throat of a perfidious governor in 1220,[126] and an early 14th century chronicle mentions that his grandson Hulagu Khan did likewise to the sultan Al-Musta'sim after the fall of Baghdad in 1258 to the Mongol army.[127]

The Spanish in 16th century Americas gave horrified reports that Spanish who had been captured by the natives (who had learnt of the Spanish thirst of gold) had their feet and hands bound, and then poured molten gold down their throats, mocking their victims: "Eat, eat gold, Christians".[128]

From 19th century reports from the Kingdom of Siam (present day Thailand) it is that those who have defrauded the public treasury could have either molten gold or silver poured down his throat.[129]

A punishment for inebriation and tobacco smoking

The 16th/early-17th century prime minister Malik Ambar in the Deccan Ahmadnagar Sultanate would not tolerate inebriation among his subjects, and would pour molten lead down the mouths of those caught in that condition.[130] Similarly, in the 17th century Sultanate of Aceh Sultan Iskandar Muda (r. 1607–36) is said to have poured molten lead in the mouths of at least two drunken subjects.[131] Military discipline in 19th century Burma was reportedly harsh, with strict prohibition of smoking opium or drinking arrack. Some monarchs, it appears, had ordained pouring molten lead down the throats of those who drank anyway, "but it has been found necessary to relax this severity, in order to conciliate the army"[132]

Shah Safi I of Persia is said to have abhorred tobacco, and apparently in 1634, he prescribed the punishment of pouring molten lead in the throats of smokers.[133]

A Mongol punishment for horse thieves

According to historian Pushpa Sharma, stealing a horse was considered the most heinous offence within the Mongol army, and the culprit would either have molten lead poured into his ears, or alternatively, by breaking the spinal cord or beheading.[134]

Chinese tradition of Buddhist self-immolation

Apparently, for many centuries, a tradition of devotional self-immolation existed among Buddhist monks in China. One monk who immolated himself in AD 527, explained his intent a year before, in the following manner:

The body is like a poisonous plant; it would really be right to burn it and extinguish its life. I have been weary of this physical frame for many a long day. I vow to worship the buddhas, just like Xijian.[135]

A severe critic in the 16th century wrote the following comment on this practice:

There are demonic people ... who pour on oil, stack up firewood, and burn their bodies while still alive. Those who look on are overawed and consider it the attainment of enlightenment. This is erroneous.[136]

Japanese persecution of Christians

In the first half of the 17th century, Japanese authorities sporadically persecuted Christians, with some executions seeing persons being burnt alive. At Nagasaki in 1622, for example, some 25 monks were burnt alive,[137] and in Edo in 1624, 50 Christians were burnt alive.[138]

Inca abhorrence of sodomy

The 16th-century Spanish writer of Inca descent, Garcilaso de la Vega, was eager to show how abhorrent homosexuality was to the Incas. Relative to the Incas' colonization of some tribes, de la Vega writes the following:

Informations were brought him against certain persons guilty of Sodomy, to which sin that Countrey was much addicted: All which he took, and condemned, and burned alive; commanding their Houses to be thrown down, their Inheritances to be destroyed, their Trees rooted up, that so no steps or marks might appear of any thing which had been built, or planted by the hands of Sodomites, and that their memory, as well as their actions, might be abolished; with them they destroyed both their Wives and Children, which severity, though it may seem unjust, was yet an evidence of that abhorrence which the Incas conceived against this unnatural Crime.[139]

Stories of cannibalism

Americas

Even fateful encounters with cannibals are recorded: in 1514, in the Americas, Francis of Córdoba and 5 companions were, reportedly, caught, impaled on spits, roasted and eaten by the natives. In 1543, such was also the end of a previous bishop, Vincent de Valle Viridi.[140]

Fiji

In 1844, the missionary John Watsford wrote a letter about the internecine wars on Fiji, and how captives could be eaten, after being roasted alive:

At Mbau, perhaps, more human beings are eaten than anywhere else. A few weeks ago they ate twenty-eight in one day. They had seized their wretched victims while fishing, and brought them alive to Mbau, and there half-killed them, and then put them into their ovens. Some of them made several vain attempts to escape from the scorching flame[141]

The actual manner of the roasting process were described by the missionary pioneer David Cargill, in 1838:

When about to be immolated, he is made to sit on the ground with his feet under his thighs and his hands placed before him. He is then bound so that he cannot move a limb or a joint. In this posture he is placed on stones heated for the occasion (and some of them are red-hot), and then covered with leaves and earth, to be roasted alive. When cooked, he is taken out of the oven and, his face and other parts being painted black, that he may resemble a living man ornamented for a feast or for war, he is carried to the temple of the gods and, being still retained in a sitting posture, is offered as a propitiatory sacrifice.[142]

Immolation of widows

Indian subcontinent

Sati refers to a funeral practice among some communities of Indian subcontinent in which a recently widowed woman immolates herself on her husband's funeral pyre. The first reliable evidence for the practice of sati appears from the time of the Gupta Empire (AD 400), when instances of sati began to be marked by inscribed memorial stones.[143]

How, when, where and why, the practice of sati spread are complex issues as borne out by the discussion of Anand Yang. According to one model of history thinking, the practice of sati only became really widespread with the Muslim invasions of India, and the practice of sati now acquired a new meaning as a means to preserve the honour of women whose men had been slain. As S.S.Sashi lays out the argument, "The argument is that the practice came into effect during the Islamic invasion of India, to protect their honor from Muslims who were known to commit mass rape on the women of cities that they could capture successfully."[144]

However, as Yang contends, the practice of sati, according to the memorial stone evidence, was carried out in appreciable numbers in western and southern parts of India, and even in some areas, to have reached peak level of incidence in pre-Islamic times.[145] Some of the rulers and activist of the time sought actively to suppress the practice of sati.[146]

The British began to compile statistics of the incidences of sati for all their domains from 1815 and onwards. The official statistics for Bengal represents that the practice was much more common here than elsewhere, recorded numbers typically in the range 500-600 per year, up to the year 1829, when the British authorities banned the practice.[147] Since 19th – 20th Century, the practice remains outlawed in Indian subcontinent.

Bali and Nepal

The practice of burning widows has not been restricted to the Indian subcontinent; at Bali, the practice was called masatia and, apparently, restricted to the burning of royal widows. Although the Dutch colonial authorities had banned the practice, one such occasion is attested as late as in 1903, probably for the last time.[148] In Nepal, the practice was not banned until 1920.[149]

Traditions in sub-Saharan African cultures

C.H.L. Hahn[150] wrote that within the O-ndnonga tribe amongst the Ovambo people in modern-day Namibia, abortion was not used at all (in contrast to amongst the other tribes), and that furthermore, if two young unwed individuals had sex resulting in pregnancy, then both the girl and the boy were "taken out to the bush, bound up in bundles of grass and ... burnt alive."[151]

Legislation against the practice

In 1790, Sir Benjamin Hammett introduced a bill into Parliament to end the practice of judicial burning. He explained that the year before, as Sheriff of London, he had been responsible for the burning of Catherine Murphy, found guilty of counterfeiting, but that he had allowed her to be hanged first. He pointed out that as the law stood, he himself could have been found guilty of a crime in not carrying out the lawful punishment and, as no woman had been burnt alive in the kingdom for more than half a century, so could all those still alive who had held an official position at all of the previous burnings. The Treason Act 1790 was duly passed by Parliament and given royal assent by King George III (30 George III. C. 48).[152]

Modern burnings

No contemporary, legitimate state routinely conducts executions by burning. Like all capital punishment, it is forbidden to members of the Council of Europe by the European Convention on Human Rights. It was never routinely practiced in the United States. However, modern-day burnings in different forms typically involving extrajudicial punishments and/or vigilante-ism, does occur.

Retaliation against Nazis

Benjamin B. Ferencz, one of the prosecutors in the later Nuremberg trials who investigated in May 1945 occurrences at the Ebensee concentration camp narrated to Tom Hofmann, a family member and biographer, he was completely outraged at what the Nazis had done there. When people discovered an SS guard who attempted to flee, they tied him to one of the metal trays used to transport bodies into the crematorium. They then proceed to light the oven, and slowly roast the SS guard to death, taking him in and out of the oven several times. Ferencz said to Hofmann that at the time, he was in no position to stop the proceedings of the mob, and frankly admitted that he had not been inclined to try. Hofmann adds: "there seemed to be no limit to human brutality in wartime".[153]

Lynching of Germans in Czechoslovakia

During the Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after the end of World War II, a number of massacres against the German minority occurred. In one case of Prague in May 1945, a Czech mob hanged several Germans upside down on lampposts, doused them in fuel and set them on fire, burning them alive.[154][155]

Extrajudicial burnings in Latin America

In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, burning people standing inside a pile of tires is a common form of murder used by drug dealers to punish those who have supposedly collaborated with the police. This form of burning is called micro-ondas[156][157] (allusion to the microwave oven[158]). Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad), a film, and Max Payne 3, a video game, contain(ed) scenes depicting this practice.[159]

During the Guatemalan Civil War the Guatemalan Army and security forces carried out an unknown number of extrajudicial killings by burning. In one instance in March 1967, Guatemalan guerrilla and poet Otto René Castillo was captured by Guatemalan government forces and taken to Zacapa army barracks alongside one of his comrades, Nora Paíz Cárcamo. The two were interrogated, tortured for four days, and burned alive.[160] Other reported instances of immolation by Guatemalan government forces occurred in the Guatemalan government's rural counterinsurgency operations in the Guatemalan Altiplano in the 1980s. In April 1982, 13 members of a Quanjobal Pentecostal congregation in Xalbal, Ixcan, were burnt alive in their church by the Guatemalan Army.[161]

A young Guatemalan woman, Alejandra María Torres, was attacked by a mob in Guatemala City on 15 December 2009. The mob alleged that Torres had attempted to rob passengers on a bus. Torres was beaten, doused with gasoline, and set on fire, but was able to put the fire out before sustaining life-threatening burns. Police intervened and arrested Torres. Torres was forced to go topless throughout the ordeal and subsequent arrest, and many photographs were taken and published. Approximately 219 people were lynched in Guatemala in 2009, of whom 45 died.[162]

In May 2015, a sixteen-year-old teenage girl was allegedly burned to death in Rio Bravo by a vigilante mob after being accused by some of involvement in the killing of a taxi driver earlier in the month.[163]

In Chile during public mass protests held against the military regime of General Augusto Pinochet on 2 July 1986, engineering student Carmen Gloria Quintana, 18, and Chilean-American photographer Rodrigo Rojas DeNegri, 19, were arrested by a Chilean Army patrol in the Los Nogales neighborhood of Santiago. The two were searched and beaten before being doused in benzene and burned alive by Chilean troops. Rojas was killed, while Quintana survived but with severe burns.[164]

Lynchings and mass killings by burning in the US

During the 1980 New Mexico State Penitentiary riot, a number of inmates were burnt to death by fellow inmates, who used blow torches. Modern burnings continued as a method of lynching in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the South. One of the most notorious extrajudicial burnings in modern history occurred in Waco, Texas on 15 May 1916. Jesse Washington, a mentally challenged African-American farmhand, after having been convicted of the rape and subsequent murder of a white woman, was taken by a mob to a bonfire, castrated, doused in coal oil, and hanged by the neck from a chain over the bonfire, slowly burning to death. A postcard from the event still exists, showing a crowd standing next to Washington's charred corpse with the words on the back "This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe". This attracted international condemnation and is remembered as the "Waco Horror".[165][166]

Unconfirmed act of execution in the Soviet Union

A former Soviet Main Intelligence Directorate officer writing under the alias Victor Suvorov (aka Viktor Suworow), described, in his book Aquarium, a Soviet "traitor" being burned alive in a crematorium.[167] There has been some speculation that the identity of this officer was Oleg Penkovsky. However, during a radio interview with the Echo of Moscow, Vladimir Rezun (aka Victor Suvorov or Viktor Suworow) denied this, saying "I never mentioned it was Penkovsky".[168] No executed GRU traitors (Penkovsky aside) are known to match Rezun/Suvorov/Suworow's scant description in Aquarium.[169]

Executions in North Korea

In connection to the purge of Jang Song-taek, O Sang-hon, a deputy minister at the Ministry of Public Security (North Korea) associated with Jang, was 'executed by flamethrower' in 2014, according to unconfirmed reports.[170]

African cases

In South Africa, extrajudicial executions by burning were carried out via "necklacing", wherein rubber tires filled with kerosene (or gasoline) are placed around the neck of a live individual. The fuel is then ignited, the rubber melts, and the victim is burnt to death.[171][172]

It was reported that in Kenya, on 21 May 2008, a mob had burned to death at least 11 accused witches.[173]

Cases from the Middle East and Indian subcontinent

In India, Dr Graham Stuart Staines, an Australian Christian missionary, who, along with his two sons Philip (aged 10) and Timothy (aged 6), was burnt to death by a gang while the three slept in the family car (a station wagon), at Manoharpur village in Keonjhar District, Odisha, India on 22 January 1999. Four years later, in 2003, a Bajrang Dal activist, Dara Singh, was convicted of leading the gang that murdered Staines and his sons, and was sentenced to life in prison. Staines had worked in Odisha with the tribal poor and lepers since 1965. Some Hindu groups made allegations that Staines had forcibly converted or lured many Hindus into Christianity.[174][175]

In Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, there were some 400 instances of the burning of women in 2006. In Iraqi Kurdistan, at least 255 women had been killed in just the first six months of 2007, three-quarters of them by burning.[176]

On 19 June 2008, the Taliban, at Sadda, Lower Kurram, Pakistan, burned three truck drivers of the Turi tribe alive after attacking a convoy of trucks en route from Kohat to Parachinar, possibly for supplying the Pakistan Armed Forces.[177]

In January 2015, Jordanian pilot Moaz al-Kasasbeh was burned in a cage by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS). The pilot was captured when his plane crashed near Raqqa, Syria, during a mission against IS in December 2014.[178]

In February 2015, ISIS also burned to death 45 people in al-Baghdadi, Iraq.[179]

In August 2015, ISIS burned to death four Iraqi Shia prisoners.[180]

Bride-burning

On 20 January 2011, a 28-year-old woman, Ranjeeta Sharma, was found burning to death on a road in rural New Zealand. The police confirmed the woman was alive before being covered in an accelerant and set afire.[181] Sharma's husband, Davesh Sharma, was charged with her murder.[182]

Portrayal in film

This is an incomplete list of the movies, that depicted similar versions.

- In Carl Theodor Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (The Passion of Joan of Arc), although filmed in the late 1920s (thus without any sophisticated special effects), includes a relatively graphic and realistic treatment of Jeanne's execution; his Day of Wrath also featured a woman burnt at the stake. Many other film versions of the story of Jeanne show her death at the stake – some more graphically than others. The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc, released in 1999, ends with Jeanne slowly burnt in the marketplace of Rouen.

- In Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927), a mob attempts to execute a woman (who is actually a robot in the guise of a woman) by burning at the stake.

- In The Wicker Man (1973), a British Police Sergeant (played by Edward Woodward), after a series of tests to prove his suitability, is burned to death by the local population in a remote island off the Scottish coast inside a giant wicker cage in the shape of a man for two reasons: to assure the following year's crop harvest, and the policeman's entering heaven as a martyr.

- In Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose (1986), the innocent simpleton Salvatore (Ron Perlman) is burnt at the stake; the same fate befell Oliver Reed's character, Urbain Grandier, in Ken Russell's The Devils (1971). In 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), several people are shown being burned at the stake.

- The Last of the Mohicans (1992) features a British officer being burned at the stake by a Huron tribe, although he is shot dead by the protagonist Hawkeye (aka Nathaniel Poe) before the flames could do further harm.

- In The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), an innocent gypsy woman, Esmeralda, is nearly burned at the stake after she refuses to marry Frollo, but is rescued by the hunchback Quasimodo.

- Elizabeth (1998) used computer graphics to enhance the opening scene where three Protestants (possibly Rogers, Latimer and Ridley) are burned at the stake.

- In the original Broadway musical and its 2007 film adaption, the eponymous antihero of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street throws his partner in crime Mrs. Lovett into an industrial oven, used for turning Todd's already deceased victims into meat pies for public consumption, for having lied to him and leading him to believe that his beloved wife Lucy was dead.

- The Hills Have Eyes (2006) graphically portrays a man being burned to death while tied to a tree.

- Final Destination 3 (2006) depicts two teenage girls trapped in overheating tanning beds who are burned to death from the resulting fires.

- Silent Hill (2006) depicts death by burning as a punishment in two separate scenes.

- In Angels and Demons (2009 film adaptation), the third of four kidnapped cardinals is burned to death; later the main villain commits self-immolation inside St Peter's Basilica.

- In the film Sherlock Holmes (2009), a scene graphically portrays a United States ambassador (surnamed Standish) erupting in flames after shooting his gun, before jumping out of the window and falling into a carriage below in a vain attempt to extinguish the flames. The cause is later revealed to be a flammable liquid raining on Standish, who mistakes it for rain, combined with a spark from a rigged bullet in his gun.

- In Friday the 13th (2009), one of Jason's victims is strung up by rope over a campfire in her sleeping bag and begins to burn while screaming.

- In Saw: The Final Chapter (2010), a woman is sealed inside a Brazen Bull replica and slowly burned alive after her husband fails to save her from her trap while he watches in horror.

- Black Death (2010) includes scenes of death by fire associated with a knight assigned to witch hunting.

- The movie-within-a-movie in Even the Rain shows Columbus's forces burning Taíno leader Hatuey at the stake for his resistance to their colonization of Hispaniola.

See also

- Relaxado en persona

- List of people burned as heretics

- Spontaneous human combustion

- Witchcraft Act

- Yaoya Oshichi

References

- ↑ Murphy (2012), pp. 67–68

- ↑ Roth (2010), p. 5

- ↑ Wilkinson (2011): Senusret I incident, p. 169 Osorkon incident, p. 412

- ↑ White (2011), p. 167

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, 1.77.8, accessed at LacusCurtius

- ↑ Schneider (2008), p. 154

- ↑ Olmstead (1918) p. 66

- ↑ Reeder (2012), p. 82

- ↑ Full list in Quint (2005), p. 257

- ↑ Quotation from Ben-Menahem, Edrei, Hecht (2012), p. 111

- ↑ On this view, see for example, Zvi Gilat, Lifshitz (2013), p. 62, footnote 73

- ↑ See Watson (1998) Ulpian, section 48.19.8.2 at page 361. Callistratus, sections 48.19.28.11-12, at page 366

- ↑ Kyle (2002), p. 53

- ↑ Martydom of Polycarp http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.iv.iv.html

- ↑ Juvenal has an extended description of the tunica molesta, the punishment as meted out by Emperor Nero as contained in Tacitus matches the concept. See, for example Pagán (2012), p. 53

- ↑ Miley (1843), pp. 223–224

- ↑ Law text found in Pharr (2001), pp. 244–245 The full law was changed in context to the penalties just 20 years later by Constantine's son, Constantius II, for free citizens aiding and abetting in the abduction, to an unspecified "capital punishment". The full severity of the law wa to be kept, however, for slaves. p. 245, ibidem

- ↑ Law text in Codex Justinianus 9.11.1, as referred to in Winroth, Müller, Sommar (2006), p. 107

- ↑ Pickett (2009), p.xxi

- ↑ On ritual description, Plutarch, and in general, see Markoe (2000), pp. 132–136 On Diodorus, see Schwartz, Houghton, Macchiarelli, Bondioli (2010), Skeletal remains..do not support on phrase "the act of laughing", se for example, Decker (2001), p. 3

- ↑ Generally accepting the tradition of child sacrifice, see Markoe (2000), pp. 132–136 Generally skeptical, see Schwartz, Houghton, Macchiarelli, Bondioli (2010), Skeletal remains..do not support

- ↑ Julius Caesar, McDevitt, Bohn (1851) On penalty for conspiracy, p. 4 On criminals in large wicker frames, p. 149 On funeral human sacrifice, pp. 150–151

- ↑ This case, and a number of others in Pluskowski (2013), pp.77–78

- ↑ Hamilton, Hamilton, Stoyanov (1998), p. 13, footnote 42

- ↑ Haldon (1997), p. 333, footnote 22

- ↑ Trenchard-Smith, Turner (2010), p. 48, footnote 58

- ↑ Sumner (2007), p. 247

- ↑ Both incidents in Weiss (2004), p. 104

- ↑ Prager, Telushkin (2007), p. 87

- ↑ Kantor (2005) p. 203

- ↑ Bülau (1860), pp. 423–424

- ↑ Richards (2013), pp. 161–163

- ↑ John, Pope (2003), p. 177

- ↑ Smirke (1865), pp. 326–331

- ↑ Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision., p. 62, (Yale University Press, 1997).

- ↑ On mercy, and 50,000 estimate, for Marranos Telchin (2004), p. 41 On 30,000 estimate of Marranos killed, see Pasachoff, Littman (2005), p. 151

- ↑ These information are included in the appendix, "Historical Notes" to the novel "The Hidden Scroll" Anouchi (2009), p. 471

- ↑ Cipolla (2005), p. 91

- ↑ Stillman, Zucker (1993) On the Río de la Plata incident, see Matilde Gini de Barnatan, p. 144, on Mexico City incident, see Eva Alexandra Uchmany, p. 128

- ↑ Carr (2009), p. 101

- ↑ Anderson (2002), p. 114

- ↑ Matar (2013), p.xxi

- ↑ Already noted originally by Hunter (1886), pp. 253–254, see also Salomon, Sassoon, Saraiva (2001), pp. 345–347

- ↑ See extensive table at Portuguese Inquisition, de Almeida (1923), in particular p. 442

- ↑ See for first time Heng (2013), p. 56 on option of public repentance Puff, Bennett, Karras (2013), p. 387

- ↑ Pickett (2009), p. 178

- ↑ On Geneva and Venice, see Coward, Dynes, Donaldson (1992), p. 36

- ↑ Crompton (2006), p. 450

- ↑ Lithgow (1814), p. 305

- ↑ Osenbrüggen (1860), p. 290

- ↑ specified as men or women found guilty of same-sex sexual behaviour or guilty of having had sex with animals.

- ↑ As late as in 1730 Posen, a church robber had his right hand cut off, and the stump covered in pitch. Then, the pitch was ignited, and the person was burnt alive on a pyre as well. Oehlschlaeger (1866), p. 55

- ↑ No fixed penalty was placed on performing acts of witchcraft that had caused no harm

- ↑ All in Koch (1824) Coin forgers: Article 111, p. 52, Malevolent witchcraft: Article 109, p. 55 Sexual acts contrary to nature:Article 116, p. 58, Arson:Article 125, p. 61, Theft of sacred objects: Article 172, p. 84

- ↑ Osenbrüggen (1854), p. 21 For a similar, more modern assessment, as well as locating the incident to Hötzelsroda, see Dietze (1995)

- ↑ Last name "Mothas" used in extended account in Bischoff, Hitzig (1832), real name "Thomas" given in Herden (2005), p. 89

- ↑ On manner of execution in the original account, see Bischoff, Hitzig (1832), p. 178 Contemporary newspaper notice, Hübner (1804), p. 760, column 2

- ↑ Original account by investigating police officer Heinrich L. Hermann, Hermann (1818) Gustav Rudbrach's mention Rudbrach (1992), p. 247 Precise moment of strangulation Gräff (1834), p. 56 Modern newspaper article Springer (2008), Das Letzte Feuer

- ↑ Osenbrüggen (1854), pp. 21–22, footnote 83

- ↑ Thurston (1912) Witchcraft, 2010 web resource.

- ↑ professional researchers in the 19th, and early 20th century tended to refuse giving any quantification at all but, when pushed, typically landed on about 100,000 to 1 million victims

- ↑ A lowest bound of 30,000 and a highest upper bound of 100,000 still within acceptability, but minority, of professional researchers supporting either of them.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Behringer (1998) on the history of witch-counting, and on specialist academic consensus, Neun Millionen Hexen Originally published in GWU 49 (1998) pp. 664–685, web publication 2006

- ↑ Contemporary description of the burning at Ile-des-Javiaux in Barber (1993), p. 241

- ↑ Extracts of eyewitness report at website of Columbia University, Peter from Mladonovic (2003), How was executed Jan Hus

- ↑ Reconstruction of Joan of Arc's death scene in Mooney, Patterson (2002), pp. 1–2 excerpt from Mooney (1919)

- ↑ Eyewitness account provided in Landucci, Jarvis (1927), pp. 142–143

- ↑ According to eyewitness Alexander Ales, Hamilton entered the pyre at noon, and died after six hours burning, see Tjernagel (1974, web reprint), p. 6

- ↑ Description of John Frith's death in Foxe, Townsend, Cattley (1838), p. 15

- ↑ Detailed description of Servetus' death at Kurth (2002) Out of the Flames

- ↑ A perfunctory official notice of the manner of his death 17 February 1600, is contained in Rowland (2009), p. 10

- ↑ Apparently, Grenadier had been promised to be strangled prior to his burning, but his executioners reneged on that promise as he was fastened to the stake. See modern monograph Rapley (2001),. in particular pp. 195–198, for a classic description, see Alexandre Dumas on the execution details in Dumas (1843), pp. 424–426

- ↑ Alan Wood describes Avvakum's execution as follows: Avvakum and three fellow prisoners were led from their icy cells to an elaborate pyre of pinewood billets and there burned alive. The tsar had finally rid himself of "this turbulent priest", Wood (2011), p. 44

- ↑ Foxe, Milner, Cobbin (1856), pp. 608–609

- ↑ Foxe, Milner, Cobbin (1856), pp. 864–865

- ↑ Foxe, Milner, Cobbin (1856), pp. 925–926

- ↑ For Denmark, see for example, Burns (2003), pp. 64–65

- ↑ John Foxe is particularly mentioned in being assiduous at documenting such cases of persecutions. See, Miller (1972), p. 72

- ↑ For claim of being last heretic burned at the stake, see for example, Durso (2007), p. 29

- ↑ Sayles (1971) p. 31

- ↑ Richards (1812), p. 1190

- ↑ Willis-Bund (1982), p. 95

- ↑ Direct citation in McLynn (2013), p. 122

- ↑ McLynn (2013), p. 122

- ↑ Comprehensive list at capitalpunishmentuk.org, Burning at the stake.

- ↑ O'Shea (1999), p. 3

- ↑ See website article, The Case of Catherine Hayes at rictornorton.co.uk See also the detailed synthesis at capitalpunishmentuk.org, Catherine Hayes burnt for Petty Treason

- ↑ "Some time in the 1590s, Anne became a Roman Catholic." Wilson (1963), p. 95 "Some time after 1600, but well before March 1603, Queen Anne was received into the Catholic Church in a secret chamber in the royal palace" Fraser (1997), p. 15 "The Queen ... [converted] from her native Lutheranism to a discreet, but still politically embarrassing Catholicism which alienated many ministers of the Kirk" Croft (2003), pp. 24–25 "Catholic foreign ambassadors—who would surely have welcomed such a situation—were certain that the Queen was beyond their reach. 'She is a Lutheran', concluded the Venetian envoy Nicolo Molin in 1606." Stewart (2003), p. 182 "In 1602 a report appeared, claiming that Anne ... had converted to the Catholic faith some years before. The author of this report, the Scottish Jesuit Robert Abercromby, testified that James had received his wife's desertion with equanimity, commenting, 'Well, wife, if you cannot live without this sort of thing, do your best to keep things as quiet as possible.' Anne would, indeed, keep her religious beliefs as quiet as possible: for the remainder of her life — even after her death — they remained obfuscated." Hogge (2005), pp. 303–304

- ↑ Pavlac (2009), p. 145

- 1 2 de Ledrede, Wright (1843)

- ↑ de Ledrede, Davidson, Ward (2004)

- ↑ Story of flight in contemporary chronicle Gilbert (2012), p.cxxxiv

- 1 2 McCullough (2000), The Fairy Defense

- ↑ Scott (1940)p. 41

- ↑ CelebrateBoston.com (2014), "Maria, Burned at the Stake"

- ↑ Mark and Phillis Executions (2014)

- ↑ McManus (1973), p. 86

- ↑ Hoey (1974),Terror in New York–1741

- ↑ De las Casas (1974), pp. 34–35

- ↑ Carvacho (2004), p. 62 "y que habiendo llegado el caso de practicar lo determinado por el Consejo en auto de 4 de febrero de 1732, ... acordaron, después de revisar la causa de Mariana de Castro y lo determinado por la Suprema el 4 de febrero de 1732"

- ↑ Waddell (1863), p. 19

- ↑ Blake (1857), pp. 154–155

- ↑ Woblers (1855), p. 205

- ↑ St. Clair (2008) Hydra incident, p.xxiv, those suspected of hiding money, p. 45, the three Turkish children, p. 77, baked in ovens, p. 81,

- ↑ Zurkhana,Houtsma (1987), p. 830

- ↑ Digby (1853), pp. 342–345

- ↑ De Thevenot,Lovell (1687), p. 69

- ↑ Moryson, Hadfield (2001), p. 171

- ↑ Braithwaite(1729)On apostates citation, see p. 366, on the conditional fate of non-Muslims, see p. 355

- ↑ Shaw (1757), p. 253

- ↑ Stillman (1979), pp. 310–311

- ↑ Kantor (1993), p. 230

- ↑ JOS Calendar Conversion Results, Hirschberg (1981), p. 20