Early Streets of Brisbane

| Early Streets of Brisbane | |

|---|---|

|

Early drawing of a section of the town of Brisbane, Queensland including the Convict Hospital, 1835 | |

| Location | Sections of Albert Street, George Street, William Street, North Quay, Queen's Wharf Road, Brisbane City, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 27°28′20″S 153°01′30″E / 27.4723°S 153.0251°ECoordinates: 27°28′20″S 153°01′30″E / 27.4723°S 153.0251°E |

| Design period | 1824–1841 (convict settlement) |

| Built | 1825– |

| Official name: Early Streets of Brisbane | |

| Type | archaeological |

| Designated | 16 July 2010 |

| Reference no. | 700011 |

| Significant period | 1825–current |

| Significant components | archaeological potential |

Location of Early Streets of Brisbane in Queensland | |

The Early Streets of Brisbane is a heritage-listed archaeological site at sections of Albert Street, George Street, William Street, North Quay, Queen's Wharf Road, Brisbane City, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was built from 1825 onwards. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 16 July 2010.[1]

History

In May 1825 Lieutenant Henry Miller moved the Moreton Bay penal colony from the Redcliffe Peninsula to the northern bank of the Brisbane River. This was an elevated location with water holes and cooling breezes. The southern bank was a cliff of rock, suitable for building material, and a fertile flood plain. The settlers faced hardship and privation and the paucity of resources combined with thick sub-tropical vegetation made settlement difficult.[2]:35 Between 1826 and 1829, the number of prisoners in the settlement rose from 200 to 1000 and the plight of the convicts whose labour was to establish the settlement was dire.[1]

The site of Brisbane Town was an ongoing issue, with Commandant Patrick Logan proposing that the settlement be moved to Stradbroke Island. However, the difficulties of crossing the bay saw this plan abandoned. Logan continued to seek alternative sites, establishing a number of outstations including Eagle Farm and Oxley Creek.[3]:25 Despite the continued uncertainty about the future of Brisbane Town, building had continued under Commandant Logan, who is given credit for laying out the earliest permanent foundations. Logan was responsible for the building of Brisbane's only surviving convict-constructed buildings: the Commissariat Store and the Old Windmill.[1][3]:28

Convict numbers fell 75 percent between 1831 and 1838 by which time the area under cultivation shrank from 200 hectares to only 29.[2]:47 On 10 February 1842 Governor Gipps declared Moreton Bay open for Free Settlement.[1][2]:48

The Moreton Bay Penal Settlement during its 15 years of operation consisted of a range of buildings including barracks for convicts and troops, officers' quarters, dwellings for the Commandant, chaplain, Commissariat officer, surgeon, Commandant's clerk and engineer, a military and convict hospital, the Commissariat Store, and various stores, barns and sheds. The settlement also included a wharf, wells, a flagstaff, gardens and a lumber yard.[1]

The Commandant's cottage was constructed in 1825 on the site of the old Government Printing Office building (now the Public Service Club between William and George Streets. It was a wooden building with brick chimneys. In 1826 a detached brick building was built to the rear of the Commandant's house.[4]:46–47 A line of buildings ran from the Commandant's house to the first military barracks along present-day William Street. These buildings included the Engineer's cottage on the corner of William and Elizabeth Streets in what is now known as Queens Gardens. The cottage was associated with the first lumber yard on this block, which also contained engineer's stores and workshops.[1][4]:47

The first military barracks were constructed in 1825 as two slab huts for the sergeant, corporal and 12 privates, and separate huts for the married couples on the corner of Queen Street and North Quay, site of the present Brisbane Square. The barracks were later moved to the other side of Queen Street and replaced by the second lumber yard in 1831. The first prisoner accommodation also consisted of slab huts, probably at the intersection of Queen and Albert Streets; stone barracks were constructed in 1829. The first Commissariat Store was constructed as a long, low slab building near the corner of Elizabeth and Albert Streets and was later used as a barn, after the stone Commissariat Store was built in 1829.[4]:47–48 The first Commissariat Store appears to have been situated within the alignment of the present day Elizabeth Street.[1]

The only entry point into the settlement was via the wharf on the Brisbane River. Initially known as the King's Wharf, or King's Jetty, it was constructed by 1827 when the boat crew's hut and boat builder's shed were first occupied. A crane was constructed on the end of the wharf in order to transfer goods from the arriving ships to the shore.[4]:illustration 36 The wharf was situated on the river bank opposite the Commissariat Store on Queen's Wharf Road. The main thoroughfare into the settlement was up the steep river bank following the present day alignment of Queen's Wharf Road.[4]:illustration 59 Pedestrians were able to enter the settlement through the vacant land immediately northwest of the Commissariat Store, in what is today known as Miller Park.[1][5]:19

A hospital was completed in 1827, after much government bungling over plans and approvals, on the block bounded by North Quay, Adelaide, George and Ann Streets, with the buildings extending into the current alignment of Adelaide Street. The windmill tower which still stands on Wickham Terrace was likely completed in late 1828, with a treadmill added before September 1829.[1]

The Prisoners' Barracks were constructed between 1827 and 1830 to house up to 1000 convicts and was the largest stone building in the settlement at the time. The barracks were situated with the frontage along present-day Queen Street, on the block surrounded by Albert, Adelaide, George and Queen Streets. The barracks consisted of a multi-storey stone building with a central archway and a large walled yard to the rear. Several smaller buildings were situated in the yard on the far side of what would become Burnett Lane.[1][4]:87–88

The dominant archway of the Prisoners Barracks extended approximately 10 metres through the building from the Queen Street frontage towards Adelaide Street opening into the large walled yard. The yard was the site of Moreton Bay's first public execution in 1830. Within the archway itself, strategically situated for all incoming and existing convicts to see, was the flogging triangle. Records indicate that in the period between February and October 1828 alone, over 11,000 lashes were inflicted on 200 convicts; this included 128 sentences of 50 or more lashes. The average in New South Wales was 41 lashes per sentence. The barracks were used from 1860 to 1868 as the court house and for Queensland's first Parliament. The barracks were demolished in 1880 with commercial redevelopment of the area in the early to mid-1880s particularly the buildings along Queen Street backing onto Burnett Lane, many of which are still extant (Manwaring Building, Gardams Building, Hardy Brothers Building, Edwards and Chapman Building, Colonial Mutual Chambers, Palings Building, Allan and Stark Building).[1][4]:118[6][7]

Beside the Prisoners' Barracks, along the Queen Street alignment towards the river, a row of single-story brick buildings were erected. The functions of the six apartments of these buildings changed over time including use as the Commissariat Officer's residence, school room, guard house, Superintendent of Convicts' residence, gaol room, solitary cells, married soldiers' residences, and a military school.[1][4]:87–88

The Chaplain's house was constructed in 1828, halfway between the Commandant's house and the Engineer's cottage, on the site now occupied by the former Lands Administration Building (now Treasury Hotel) between William and George Streets. Described in 1829 as a handsome brick house, it was later divided into two dwellings, and occupied at various times by the Assistant Surgeon and the Commissariat Officer.[1][4]:96, 117

The Government Gardens were established in 1828 to the southwest of the settlement on the site of the present day City Botanic Gardens on Alice Street. The garden was under the charge of the Superintendent of Agriculture and produced a wide range of vegetables including cabbage, cauliflower, peas, beans, potatoes and pumpkins, as well as fruit trees and plants such as banana, pineapple, citrus, and apple. The Gardener's house, octagonal in shape and consisting of three rooms surrounded by verandahs, was also situated in the gardens.[4]:112–113, 188 The route of the roadway along the western end of the settlement from the Prisoners' Barracks to the Government Gardens overlaps with the current Albert Street on the block between Margaret and Alice Streets.[1][4]:illustration 129

The new Commissariat Store, Brisbane was constructed in 1828 and 1829, on its site between present day William Street and Queens Wharf Road. The two story utilitarian building was constructed of local porphyry and sandstone, with its ground and second floor doors opening towards the river and the wharf.[5]:13 Used for various stores and government purposes over its history, it is one of only two extant structures from the convict period.[1]

One of the major thoroughfares of the settlement, taken by Allan Cunningham in his 1829 survey, ran along the rear of the Prisoners Barracks towards a pathway up to the windmill tower and to the Kangaroo Point Road. The alignment of this pathway follows the current alignment of Adelaide Street, from George Street to Albert Street, where the original pathway crossed Wheat Creek.[1][4]:116, illustration 59

Additional hospital accommodation was erected in 1830/31 adjacent to the existing hospital, situated between present day North Quay and George Street. This included a cottage for the Medical Officer and a building to serve as the Military Hospital.[4]:153 The new Military Barracks were also constructed in 1831. Designed for 100 rank and file, the barracks compound also included a guard house and a dwelling for two subaltern officers. The barracks were constructed on what is today the Treasury Building (Treasury Casino) while the former barracks site (situated at Brisbane Square) was converted to the lumber yard.[1][4]:154

In 1839, in preparation for the opening of Moreton Bay to free settlement, surveyors were sent from Sydney to draw maps of the district and prepare town plans so the land could be put up for sale. The town plan undertaken by Robert Dixon (Plan MT3, DERM 1840) is based on an earlier 1839 plan but superimposes the proposed street plan for the free town of Brisbane with square blocks of 10 chains.[4]:264, illustration 118[8]:5 Additional features depicted in these plans include a well situated in what is now George Street, near the intersection with Burnett Lane; a flagstaff in the centre of what is now William Street, close to the northwest boundary of Miller Park; and a range of gardens. The garden areas included military gardens and Dixon's garden behind the Military Barracks in the block bounded by Queen, George, Elizabeth and Albert Streets; Whyte's garden to the northwest of the Prisoners Barracks, through which Burnett Lane now runs; Handt's garden and Kent's garden to the rear of the Chaplain's house and Commandant's house, today overlain by parts of Elizabeth, George and Charlotte Streets; the Commandant's garden adjacent to the Commissariat Store along William Street and down towards Alice Street; and Paget's garden and Dr Ballard's garden adjacent to the Hospital, in the location of George and Ann Streets. Barns and a piggery indicated on Dixon's 1840 plan appear to have been situated within the current alignment of Charlotte Street.[1]

On 10 February 1842 Governor George Gipps declared the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement closed and the district open for free settlement.[4]:303–304 A number of revised plans for the town were made, particularly after a visit by Governor Gipps, with the 1843 plan by surveyor Henry Wade (Plan MT8, DERM 1843) being the one adopted as the present day plan of the Brisbane CBD.[1][4]:307–308, illustration 129

Only three other places within the Brisbane CBD dating to the penal settlement period are entered in the Queensland Heritage Register:[1]

Archaeological investigations at the Commissariat Store, Old Windmill and 40 Queen Street (Brisbane Square) have identified archaeological remains dating to the penal period. The original cemetery site at Skew Street is also well known as is the children's burial site at North Quay. The remnants of the original Commandant's House were also unearthed in the mid 1980s without any archaeological investigation.[1]

Description

The Early Streets of Brisbane includes Lot 1 on AP3481, Lot 12 on SP180752 and the following road reserves:[1]

- Adelaide Street, between George and Albert Street, excluding Albert Street intersection

- Albert Street, between Margaret and Alice Streets, excluding Margaret Street intersection

- Alice Street, between William and Albert Streets including Albert Street intersection

- Burnett Lane – Charlotte Street, between George and Albert Streets, excluding Albert Street intersection

- Elizabeth Street, between George and Albert Streets, including George Street intersection

- George Street, between Adelaide and Queen Streets, including Adelaide Street intersection

- George Street, between Queen and Elizabeth Streets, including Elizabeth Street intersection

- George Street, from Charlotte Street to end, at boundary with QUT campus, including all intersections

- North Quay, between Ann and Queen Streets, including Adelaide Street intersection

- Margaret Street, between William and George Streets, including intersections

- Queen's Wharf Road, between Margaret and Elizabeth Street alignments

- Part of Queen's Wharf Road, adjacent to Queen Street

- Part of William Street, between Queen and Elizabeth Streets, excluding the extent of Lot 300 CP966930, the road surface situated directly above it, and intersections

- William Street, between Elizabeth and Alice Streets, excluding Elizabeth Street intersection

The Early Streets of Brisbane excludes the volumetric parcels, being Lot 42 SP145288, Lot 587 SL10897, and Lot 588 SL10897.[1]

All roads are modern bituminised surfaces with white and yellow line markings. All roads are kerbed and channelled with either concrete or porphyry stone blocks in the kerbing, and concreted gutters. The road reserves include the footpaths which consist of a range of surfacing materials including brick paving, concrete and bitumen.[1]

Burnett Lane

Burnett Lane is a narrow street that runs between George Street and Albert Street between and parallel to Adelaide Street and Queen Street. It is Brisbane's oldest laneway and is named after James Charles Burnett, one of Queensland's earliest surveyors.[9] During the penal colony years, it was used as a prison exercise yard and for floggings and hangings. Later it became the tradesmen's entrance to buildings fronting Queen and Adelaide Streets. In 2008 Brisbane City Council announced that Burnett Lane would be refurbished and integrated into the Queen Street Mall precinct, resulting the lane developing into a popular cafe and bar precinct, but delivery vehicles pose a problem for pedestrians in this narrow street.[10][11]

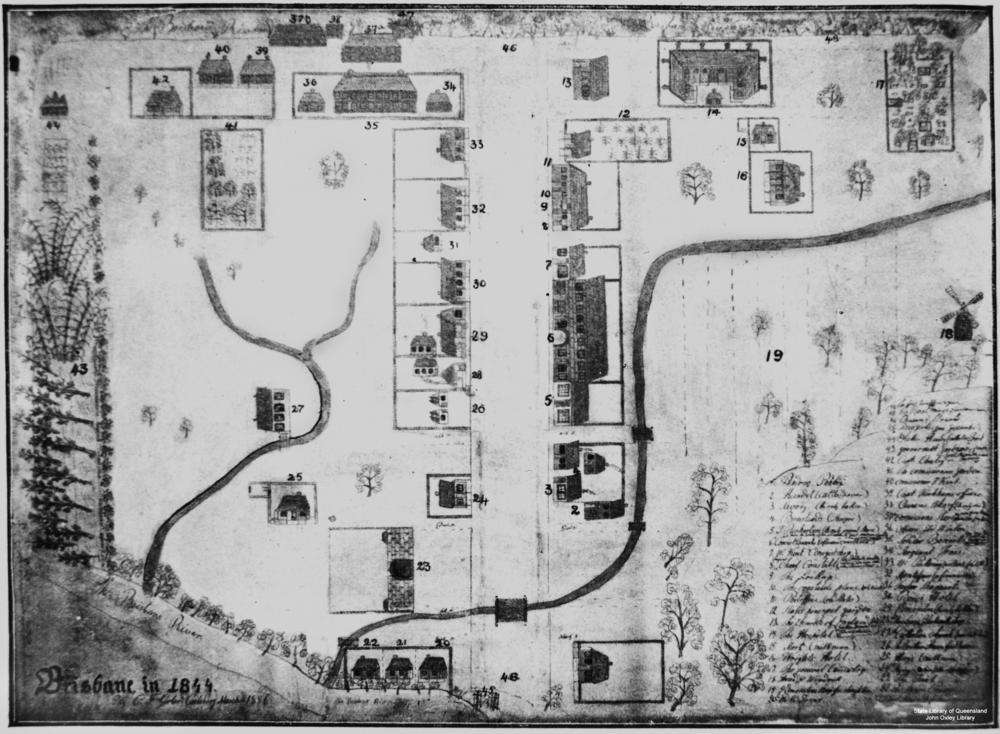

1844 map

Map legend

|

|

|

Heritage listing

Early Streets of Brisbane was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 16 July 2010 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The Early Streets of Brisbane have the potential to contain archaeological artefacts that are an important source of information about Queensland's history. Potential subsurface remains will demonstrate the establishment, evolution and pattern of settlement of early Brisbane as a penal colony. Evidence of this first European occupation of Brisbane is extremely rare given the substantial development into a modern city. Archaeological remains associated with the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement will provide evidence and understanding of a particular type of place - that of colonial penal settlements - this being the first and only example of its type in Queensland.[1]

Survey plans of the initial settlement overlaid with the proposed (and current) street plan exist, enabling the clear identification of locations of the early settlement structures. Although the current alignment of Queen Street remains substantially the same as its original, the current street plan alignment overlaps with allotments from the penal settlement period. This leads to a high potential for the remains of buildings being situated within the current street alignments. The construction of Brisbane's streets has seen a deposition and build-up of layers rather than being cut down and removed, thereby preserving earlier cultural deposits. This was evident during work undertaken for the construction of Queens Plaza on the corner of Queen and Edward Streets in 2003 which clearly demonstrated the buildup of layers in the stratigraphic profile of Queen Street. The streets therefore are the least disturbed areas in the Brisbane Central Business District (CBD) with the most potential for the presence of the earliest remains of Queensland's European settlement.[1]

The Streets have the potential for subsurface remains of the full range of activities occurring in the penal settlement related to the Prisoners Barracks, Commandant's House and Office, Commissariat Store and Office, Officer's Quarters, and Military Barracks, Military and Convict Hospitals, other dwellings, gardens, stores and barns. The archaeological investigation of the Early Streets of Brisbane has the potential to provide information about unmapped buildings and features, and to provide information about the use of mapped structures whose purpose is historically unknown. The remains of buildings, features and other artefacts have the potential to provide insight into the material culture and life ways of the convicts, soldiers and administrators of the penal settlement. They also have the potential to provide an insight into the social divisions between these groups, and the social development of early Queensland. This will contribute information to the collective understanding of convict sites around Australia and the place of Queensland in the system of forced migration and punishment of the 18th and 19th centuries.[1]

Given the accumulation of material from the initial European settlement of Brisbane to the present day, there is also the potential for archaeological remains from subsequent periods to be recovered. This will contribute to the full history of development of Queensland's capital city of Brisbane.[1]

The Early Streets of Brisbane have been assessed as part of the Brisbane City CBD Archaeological Plan as being "Exceedingly Rare" given their association with the penal settlement phase of Brisbane.[12][13] The level of disturbance has been designated as "Intact" given the minor subsurface works undertaken and the tendency for accumulation of deposits when constructing or renewing road surfaces. This combination of being designated "exceedingly rare" and "intact" leads to the categorisation of the Early Streets of Brisbane as having "Exceptional Archaeological Research Potential".[1]

Being the least disturbed areas of the Brisbane City CBD with high potential for the earliest remains of the colony's establishment, archaeological investigation of the Early Streets of Brisbane has the potential to answer important research questions critical to Queensland's history. Such questions could focus on but are not limited to the identification of the locations and purposes of previously undocumented penal settlement buildings, questions of social status, individual and collective living conditions, and an understanding of the processes of forced migration and punishment.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 "Early Streets of Brisbane (entry 700011)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Evans, R. (2007) A History of Queensland. Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

- 1 2 Johnston, W. R. (1988) Brisbane: The first thirty years. Boolarong Publications, Brisbane.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Steele, J. G. (1975) Brisbane Town in Convict Days, 1824–1842. University of Queensland Press, Brisbane.

- 1 2 Kennedy, M. (1998) Commissariat Store Conservation Plan. Department of Public Works, Brisbane.

- ↑ Evans, R. and C. Ferrier (eds) (2004) Radical Brisbane: An Unruly History. The Vulgar Press, Melbourne.

- ↑ de Vries, S. and J. de Vries (2003) Historic Brisbane: Convict Settlement to River City. Pandanus Press, Brisbane.

- ↑ Hadwen, I., J. Hogan and C. Nolan (2004) Brisbane's Historic North Bank: 1825–2005. Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Brisbane.

- ↑ "First Surveys". Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ "Burnett Lane incorporated into Queen Street Mall". Brisbane Times. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Panayotov, Jodi (6 June 2014). "Brisbane Laneways: a guide". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Department of Environment and Resource Management (2009) Brisbane City Central Business District Archaeological Plan, November 2009.

- ↑ University of Queensland Cultural and Heritage Unit (2009) The Brisbane City CBD Archaeology Plan: Phases 2, 3 and 4, UQCHU Report No. 432b. Unpublished report to the Department of Environment and Resource Management.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU license (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU license (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU license (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU license (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).