Bruce Reynolds

| Bruce Reynolds | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Bruce Richard Reynolds 7 September 1931 Charing Cross Hospital, Strand, London, England, UK |

| Died |

28 February 2013 (aged 81) Croydon, London, England, UK |

| Other names |

Keith Clement Miller Keith Hillier |

| Occupation | Messenger, Cyclist, Antiques dealer |

| Spouse(s) | Frances (until her death) |

| Children | Nick Reynolds |

| Motive | Financial gain/enjoyment |

| Conviction(s) |

1957: Assault and robbery, 3½ years HMP Wandsworth 1969: Great Train Robbery, 25 years HMP Durham[1] 1980: Drug dealing, 3years HMP Maidstone |

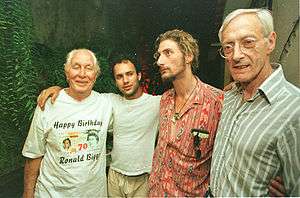

Bruce Richard Reynolds (7 September 1931[2] – 28 February 2013)[3] was an English criminal, who masterminded the 1963 Great Train Robbery.[4] At the time it was Britain's largest robbery, netting GB£2,631,684,[5] which was equivalent to £41 million in July 2013.[6] Reynolds spent five years on the run before being sentenced to 25 years in 1969. He was released in 1978. He wrote three books and performed with the band Alabama 3, for whom his son, Nick, plays.[7]

Early life

Bruce Richard Reynolds was born at Charing Cross Hospital, in the Strand, central London, the only child of Thomas Richard and Dorothy Margaret (née Keen). He was initially brought up in Putney, and his mother, a nurse, died in 1935 when he was aged four. His father, a trade-union activist at the Ford Dagenham assembly plant, married again, and the family moved to Gants Hill.[5] Reynolds found it difficult to live with his father and stepmother, choosing often to stay with one or other of his grandmothers.[2] During the London Blitz of the Second World War he was evacuated to Suffolk and then to Warwickshire.

On leaving school at 14½, Reynolds failed the eyesight test to join the Royal Navy,[8] and decided he wanted to become a foreign correspondent, so he applied in person for a job at Northcliffe House.[8] Employed first as a messenger boy, he then worked in the accounts department of the Daily Mail.[9] By the age of 17 he had become bored with the routine and was working in the Bland/Sutton Institute of Pathology at Middlesex Hospital,[8] before joining Claud Butler as a bicycle messenger and a member of their semi-professional racing team,[5] where he first met criminals and began a life of crime.[1]

Career

After undertaking some petty crime and spending time in HMP Wormwood Scrubs and Borstal[5] for theft[3] (from which he escaped and was eventually caught and sent to Reading Prison), he spent six weeks of the required two years doing National Service in the British Army, before running away to return to petty crime. Sentenced to three years in 1952 for breaking and entering, he was sent to the juvenile wing of Wandsworth Prison in London.[1] He then graduated to jewellery theft from large country houses.[1]

In 1957 Reynolds was arrested, together with Terry Hogan, for assault and robbery of a bookmaker returning from White City Greyhounds with £500.[10] The police stated their belief that the intent of the cosh attack was grievous bodily harm and not robbery. Hogan was sentenced to 2½ years and Reynolds received a year longer.[11] After spending time in HMP Wandsworth and HMP Durham, on release in 1960 he then became an antiques dealer and thief.[12]

He joined a gang with future best friend Harry Booth and future brother-in-law John Daly. Later on, he did some work with Jimmy White and met Buster Edwards at Charlie Richardson's club. Richardson in turn introduced him to Gordon Goody.[2] Having gained the moniker Napoleon,[13] in 1962 his gang stole £62,000 in a security van robbery at London Heathrow Airport. They then attempted to rob a Royal Mail train at Swindon, which netted only £700.[5] But Reynolds, now looking for his career-criminal defining moment,[1] started planning his next train robbery over a period of three months.[5]

Reynolds organised a gang of 15 men to undertake the 1963 Great Train Robbery (which he later referred to as his "Sistine Chapel ceiling").[14] After the theft, Reynolds spent six months in a mews house in South Kensington waiting for a false passport.[1] He then travelled via Elstree Airfield to Ostend, was then driven to Brussels Airport, before flying with Sabena airlines to Mexico City via Toronto.[8] Assuming the name Keith Clement Miller,[1] he was joined by his wife Frances, who changed her name to Angela, and son Nick.[13]

I was beginning to see the thief as an artist ... Nothing could match the tension, excitement and sense of fulfillment.

For Christmas 1964, the family were joined in Acapulco by fellow train robbers Buster Edwards, who had not yet been caught, and treasurer Charlie Wilson, who had escaped from HMP Winson Green.[5] Reynolds and his family later moved to Montreal, Canada, where Wilson had settled with his family, but a proposed theft of Canadian dollars was stopped due to Royal Canadian Mounted Police observation. Reynolds then moved to Vancouver, before returning that summer to the South of France.[5]

By now running low on cash, he heard a similarly sized large robbery was being planned.[5] The family returned to London, before then moving to Torquay, Devon.[16] Assuming the name Keith Hiller, the family began a life of settling into Reynolds' former childhood holiday town, before he had the urge to make contact with his old friends back in London. The Metropolitan Police whilst watching the London criminal scene realised that Hiller was in fact Reynolds, and arrested him in Torquay on 9 November 1968.[17] Offered a deal by the Director of Public Prosecutions (England and Wales) to plead guilty and avoid them pursuing his son, wife and family on further criminal charges, Reynolds agreed to plead guilty and was sentenced to 25 years.[1] All of the Great Train robbers were held in maximum security in a specially built unit at HMP Durham.[5] After making friends with both Charlie and Eddie Richardson whilst in prison, Reynolds was released from HMP Maidstone in 1978.[1]

After a failed attempt in the textile trade, he began trafficking and money laundering for many South London drugs gangs.[1] Arrested for dealing amphetamines, he was jailed in the 1980s for three years.[3]

Later life

On release he gained a profile as a media "former criminal" figure, and acted as a consultant on the film Buster, with Larry Lamb portraying Reynolds. Reynolds then published his autobiography The Autobiography of a Thief (1995).[2] In the book, Reynolds commented that the Great Train Robbery had proved a curse that followed him around, as after it no-one wanted to employ him either legally or illegally:[13]

| “ | I became an old crook living on handouts from other old crooks. | ” |

Having either spent or had removed by courts the monies that he gained through crime, by the 1990s Reynolds was living on income support in a flat in Croydon, South London, supplied by a charitable trust.[3] Reynolds' wife predeceased him.[5] He died on the afternoon of 28 February 2013 at the age of 81.[3][5][16] At the time of his death, Reynolds was working on The Great Train Robbery 50th Anniversary:1963–2013, published by Mpress in July 2013.

In popular culture

Multiple media properties and parodies have been produced about the Great Train Robbery [see Details of the Great Train Robbery and the robbers]. Examples featuring Bruce Reynolds include: Die Gentlemen bitten zur Kasse (The Gentleman Prefers Payment, also known as Great British Train Robbery) which aired on TV-Dreiteiler in 1966 and featured Horst Tappert as Reynolds, Robbery (1967) with Stanley Baker as a character based upon Reynolds, and Buster (1988) with Larry Lamb as Reynolds.

In 2008, Shaun Micallef parodied Reynolds in Series 2, Episode 9 of an Australian Satirical Comedy News Series Newstopia. In 2012, Reynolds was portrayed in the television series Mrs Biggs by Jay Simpson.

He was also the subject of the song "Have You Seen Bruce Richard Reynolds", originally by Nigel Denver and later covered by the UK band Alabama 3. Reynolds himself appears on the Alabama 3 version.[18]

On the day that Biggs died, 18th December 2013, the BBC broadcast the first of a two part series, The Great Train Robbery, which provides a dramatisation of the events first from the criminals' perspective and then from that of the police. The program had already been scheduled for broadcast on that date.[19]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "In conversation with... Bruce Reynolds". Idler magazine. 14 March 1996. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruce Reynolds (1995). The Autobiography of a Thief: The Man Behind The Great Train Robbery. ISBN 0753510502.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Great Train Robber Bruce Reynolds dies aged 81". BBC News. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Bruce Reynolds". The Daily Telegraph (Telegraph Media Group). 1 March 2013. p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Obituary: Bruce Reynolds". The Guardian. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Jake Arnott (12 July 2013). "Great Train Robbery: How Bruce Reynolds became a writer". BBC News. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Reynolds, Bruce (29 January 2008). "Comment: Anyone can steal - but few get away". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Live chat with Bruce Reynolds". Evening Standard. 8 August 2003. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Interview: One of your very uncommon criminals". The Guardian. 1 April 1995.

- ↑ "Alleged Assault On Bookmaker Two Men For Trial". The Times. 28 December 1957.

- ↑ Assault On Bookmaker, The Times 17 January 1958

- ↑ The Great Train Robbery

- 1 2 3 "Bruce Reynolds, the Great Train Robbery mastermind, dies". Daily Telegraph. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Adam Bernstin, The Washington Post (2 March 2013). "Bruce Reynolds, 'Robbery' architect". Newsday. p. A26.

- ↑ Stephen Miller (2013-03-01), "Leader of Notorious Train Heist", The Wall Street Journal, Remembrances, p. A9

- 1 2 The "Train Robber House"

- ↑ Guy Henderson (28 February 2013). "How Great Train Robber Bruce Reynolds was run to ground in Torquay". Thisissouthdevon.co.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Track List for Outlaw 2005 by Alabama 3, Alabama 3 official site, retrieved 13 January 2015

- ↑ Campbell, Duncan (18 December 2013). "Ronnie Biggs picks his moment one last time". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|