Broken windows theory

| Criminology and penology |

|---|

|

The broken windows theory is a criminological theory of the norm-setting and signaling effect of urban disorder and vandalism on additional crime and anti-social behavior. The theory states that maintaining and monitoring urban environments to prevent small crimes such as vandalism, public drinking, and toll-jumping helps to create an atmosphere of order and lawfulness, thereby preventing more serious crimes from happening.

The theory was introduced in a 1982 article by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling.[1] Since then it has been subject to great debate both within the social sciences and the public sphere. The theory has been used as a motivation for several reforms in criminal policy, including the controversial mass use of "stop, question, and frisk" by the New York City Police Department.

Article and crime prevention

James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling first introduced the broken windows theory in an article titled Broken Windows, in the March 1982 The Atlantic Monthly.[1] The title comes from the following example:

Consider a building with a few broken windows. If the windows are not repaired, the tendency is for vandals to break a few more windows. Eventually, they may even break into the building, and if it's unoccupied, perhaps become squatters or light fires inside.Or consider a pavement. Some litter accumulates. Soon, more litter accumulates. Eventually, people even start leaving bags of refuse from take-out restaurants there or even break into cars.

Before the introduction of this theory by Wilson and Kelling, Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford psychologist, arranged an experiment testing the broken-window theory in 1969. Zimbardo arranged for an automobile with no license plates and the hood up to be parked idle in a Bronx neighbourhood and a second automobile in the same condition to be set up in Palo Alto, California. The car in the Bronx was attacked within minutes of its abandonment. Zimbardo noted that the first "vandals" to arrive were a family – a father, mother and a young son – who removed the radiator and battery. Within twenty-four hours of its abandonment, everything of value had been stripped from the vehicle. After that, the car's windows were smashed in, parts torn, upholstery ripped, and children were using the car as a playground. At the same time, the vehicle sitting idle in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week until Zimbardo himself went up to the vehicle and deliberately smashed it with a sledgehammer. Soon after, people joined in for the destruction. Zimbardo observed that majority of the adult "vandals" in both cases were primarily well dressed, Caucasian, clean-cut and seemingly respectable individuals. It is believed that, in a neighborhood such as the Bronx where the history of abandoned property and theft are more prevalent, vandalism occurs much more quickly as the community generally seems apathetic. Similar events can occur in any civilized community when communal barriers—the sense of mutual regard and obligations of civility—are lowered by actions that suggest apathy.[1]

The article received a great deal of attention and was very widely cited. A 1996 criminology and urban sociology book, Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities by George L. Kelling and Catharine Coles, is based on the article but develops the argument in greater detail. It discusses the theory in relation to crime and strategies to contain or eliminate crime from urban neighborhoods.[2]

A successful strategy for preventing vandalism, according to the book's authors, is to address the problems when they are small. Repair the broken windows within a short time, say, a day or a week, and the tendency is that vandals are much less likely to break more windows or do further damage. Clean up the sidewalk every day, and the tendency is for litter not to accumulate (or for the rate of littering to be much less). Problems are less likely to escalate and thus "respectable" residents do not flee the neighborhood.

Though police work is crucial to crime prevention, Oscar Newman, in his 1972 book, Defensible Space, wrote that the presence of police authority is not enough to maintain a safe and crime-free city. People in the community help with crime prevention. Newman proposes that people care for and protect spaces they feel invested in, arguing that an area is eventually safer if the people feel a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the area. Broken windows and vandalism are still prevalent because communities simply do not care about the damage. Regardless of how many times the windows are repaired, the community still must invest some of their time to keep it safe. Residents' negligence of broken window-type decay signifies a lack of concern for the community. Newman says this is a clear sign that the society has accepted this disorder—allowing the unrepaired windows to display vulnerability and lack of defense.[3] Malcolm Gladwell also relates this theory to the reality of NYC in his book The Tipping Point.[4]

The theory thus makes two major claims: that further petty crime and low-level anti-social behavior is deterred, and that major crime is prevented as a result. Criticism of the theory has tended to focus disproportionately on the latter claim.

Informal social controls

Many claim that informal social controls can be an effective strategy to reduce unruly behavior. Garland 2001 expresses that “community policing measures in the realization that informal social control exercised through everyday relationships and institutions is more effective than legal sanctions”.[5] Informal social control methods, has demonstrated a “get tough” attitude by proactive citizens, and expresses a sense that disorderly conduct is not tolerated. According to Wilson and Kelling, there are two types of groups involved in maintaining order, ‘community watchmen’ and ‘vigilantes’[1] The United States has adopted in many ways policing strategies of old European times, and at that time informal social control was the norm, which gave rise to contemporary formal policing. Though, in earlier times, there were no legal sanctions to follow, informal policing was primarily ‘objective’ driven as stated by Wilson and Kelling (1982).

Wilcox et al. 2004 argue that improper land use can cause disorder, and the larger the public land is, the more susceptible to criminal deviance.[6] Therefore, nonresidential spaces such as businesses, may assume to the responsibility of informal social control “in the form of surveillance, communication, supervision, and intervention.”[7] It is expected that more strangers occupying the public land creates a higher chance for disorder. Jane Jacobs can be considered one of the original pioneers of this perspective of broken windows. Much of her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities focuses on residents' and nonresidents' contributions to maintaining order on the street, and explains how local businesses, institutions, and convenience stores provide a sense of having "eyes on the street."[8]

On the contrary, many residents feel that regulating disorder is not their responsibility. Wilson and Kelling found that studies done by psychologists suggest people often refuse to go to the aid of someone seeking help, not due to a lack of concern or selfishness “but the absence of some plausible grounds for feeling that one must personally accept responsibility”[1] On the other hand, others plainly refuse to put themselves in harm's way, depending on how grave they perceive the nuisance to be; a 2004 study observed that "most research on disorder is based on individual level perceptions decoupled from a systematic concern with the disorder-generating environment."[9] Essentially, everyone perceives disorder differently, and can contemplate seriousness of a crime based on those perceptions. However, Wilson and Kelling feel that although community involvement can make a difference, “the police are plainly the key to order maintenance.”[1]

Concept of fear

Ranasinghe argues that the concept of fear is a crucial element of broken windows theory, because it is the foundation of the theory.[10] She also adds that public disorder is “...unequivocally constructed as problematic because it is a source of fear.”[11] Fear is elevated as perception of disorder rises; creating a social pattern that tears the social fabric of a community, and leaves the residents feeling hopeless and disconnected. Wilson and Kelling hint at the idea, but don’t focus on its central importance. They indicate that fear was a product of incivility, not crime, and that people avoid one another in response to fear, weakening controls.[1]

Critical developments

In an earlier publication of The Atlantic released March, 1982, Wilson wrote an article indicating that police efforts had gradually shifted from maintaining order to fighting crime.[1] This indicated that order maintenance was something of the past, and soon it would seem as it has been put on the back burner. The shift was attributed to the rise of the social urban riots of the 1960s, and "social scientists began to explore carefully the order maintenance function of the police, and to suggest ways of improving it—not to make streets safer (its original function) but to reduce the incidence of mass violence".[1] Other criminologists argue between similar disconnections, for example, Garland argues that throughout the early and mid 20th century, police in American cities strived to keep away from the neighborhoods under their jurisdiction.[5] This is a possible indicator of the out-of-control social riots that were prevalent at that time. Still many would agree that reducing crime and violence begins with maintaining social control/order.

Jane Jacobs' The Death and Life of Great American Cities is discussed in detail by Ranasinghe, and its importance to the early workings of broken windows, and claims that Kelling's original interest in "minor offences and disorderly behaviour and conditions" was inspired by Jacobs' work.[12] Ranasinghe includes that Jacobs' approach toward social disorganization was centralized on the “streets and their sidewalks, the main public places of a city" and that they "are its most vital organs, because they provide the principal visual scenes."[13] Wilson and Kelling, as well as Jacobs, argue on the concept of civility (or the lack thereof) and how it creates lasting distortions between crime and disorder. Ranasinghe explains that the common framework of both set of authors is to narrate the problem facing urban public places. Jacobs, according to Ranasinghe, maintains that “Civility functions as a means of informal social control, subject little to institutionalized norms and processes, such as the law” ‘but rather maintained through an’ “intricate, almost unconscious, network of voluntary controls and standards among people… and enforced by the people themselves”[14]

Theoretical explanation

The reason why the state of the urban environment may affect crime may be described as due to three factors:

- social norms and conformity,

- the presence or lack of routine monitoring, and

- social signaling and signal crime.

In an anonymous, urban environment, with few or no other people around, social norms and monitoring are not clearly known. Individuals thus look for signals within the environment as to the social norms in the setting and the risk of getting caught violating those norms; one of those signals is the area's general appearance.

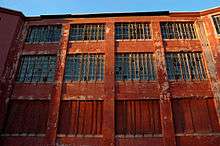

Under the broken windows theory, an ordered and clean environment—one that is maintained—sends the signal that the area is monitored and that criminal behavior is not tolerated. Conversely, a disordered environment—one that is not maintained (broken windows, graffiti, excessive litter)—sends the signal that the area is not monitored, and that criminal behavior has little risk of detection.

This theory assumes that the landscape "communicates" to people. A broken window transmits to criminals the message that a community displays a lack of informal social control, and is therefore unable or unwilling to defend itself against a criminal invasion. It is not so much the actual broken window that is important, but the message the broken window sends to people. It symbolizes the community's defenselessness and vulnerability and represents the lack of cohesiveness of the people within. Neighborhoods with a strong sense of cohesion fix broken windows and assert social responsibility on themselves—effectively giving themselves control over their space. The theory emphasizes the built environment, but must also consider human behavior.[15]

Under the impression that a broken window left unfixed leads to more serious problems, residents begin to change the way they see their community. In an attempt to stay safe, a cohesive community starts to fall apart as individuals start to spend less time in communal space to avoid potential violent attacks by strangers.[1] The slow deterioration of a community as a result of broken windows modifies the way people behave when it comes to their communal space, which in turn breaks down community control. As rowdy teenagers, drunks, panhandlers, addicts, and prostitutes slowly make their way into a community, it signifies that the community can't assert informal social control, and citizens become afraid of worse things happening. As a result, they spend less time in the streets to avoid these subjects, and feel increasingly disconnected from their community if the problems persist.

At times, residents tolerate "broken windows" because they feel they belong in the community and "know their place"—but problems arise when outsiders begin to disrupt the community's cultural fabric. This is the difference between "regulars" and "strangers" in a community. The way "regulars" act represents the culture within, whereas strangers are "outsiders" who do not belong.[15] Consequently, what were considered "normal" daily activities for residents now become uncomfortable as the culture of the community carries a different feel from what it was once.

With regard to social geography, the broken windows theory is a way of explaining people and their interactions with space. The culture of a community can deteriorate and change over time with the influence of unwanted people and behaviors changing the landscape. The theory can be seen as people shaping space as the civility and attitude of the community create spaces that are used for specific purposes by residents. On the other hand, it can also be seen as space shaping people with elements of the environment influencing and restricting our day-to-day decision making. However, with policing efforts to remove unwanted disorderly people that put fear in the public’s eyes, the argument would seem to be in favor of “people shaping space” as public policies are enacted and help to determine how we are supposed to behave. All spaces have their own codes of conduct and what is considered to be right and normal will vary from place to place.

This concept also takes into consideration spatial exclusion and social division as certain people behaving in a given way are considered disruptive and therefore unwanted. It excludes people from certain spaces because their behavior doesn't fit the class level of the community and its surroundings. A community has its own standards and communicates a strong message to criminals, through social control, that their neighborhood does not tolerate sub-standard behavior. If however, a community isn’t able to ward off would-be criminals on their own, policing efforts help. By removing unwanted people from the streets, the residents feel safer and have a higher regard for those that protect them. People of sub-standard civility who try to make a mark in the community are removed as a result of this theory.[15] Excluding the unruly and people of certain social statuses is an attempt to keep the balance and cohesiveness of a community.

Support for the theory

New York City

The book (Broken Windows) author, George L. Kelling, was hired as a consultant to the New York City Transit Authority in 1985, and measures to test the broken windows theory were implemented by David L. Gunn. The presence of graffiti was intensively targeted, and the subway system was cleaned in a special effort from 1984 until 1990. Kelling has also been hired as a consultant to the Boston Police Department and the Los Angeles Police Department.

In 1990, William J. Bratton became head of the New York City Transit Police. Bratton described George L. Kelling as his "intellectual mentor", and implemented zero tolerance of fare-dodging, faster arrestee processing methods, and background checks on all those arrested. After his election as Mayor of New York City in 1993, Republican Rudy Giuliani hired Bratton as his police commissioner to implement the strategy more widely across the city, under the rubrics of "quality of life" and "zero tolerance". Influenced heavily by Kelling and Wilson's article, Giuliani was determined to put the theory into action. He set out to prove that despite New York's infamous image of being "too big, too unruly, too diverse, too broke to manage", the city was, in fact, manageable.[16]

Giuliani's "zero-tolerance" program was part of an interlocking set of wider reforms, crucial parts of which had been underway since 1985. Bratton had the police more strictly enforce the law against subway fare evasion, public drinking, public urination, graffiti vandals, and the "squeegee men" (who had been wiping windshields of stopped cars and aggressively demanding payment). Initially, Bratton was criticized for going after "petty" crimes. The general complaint about this policy was, "Why care about panhandlers, hookers, or graffiti artists when there are more serious crimes to be dealt with?"

The main notion of the broken window theory is that small crimes can make way for larger crimes. If the "petty" criminals are often overlooked and given tacit permission to do what they want, their level of criminality might escalate to more serious offenses. Bratton's goal was to attack while the offenders are still "green", to prevent escalation to more serious criminal acts.[16] According to the 2001 study of crime trends in New York by George Kelling and William Sousa,[17] rates of both petty and serious crime fell suddenly and significantly, and continued to drop for the following ten years.

However, some later research strongly suggested that there was no benefit from the targeting of petty crime.[18] The crime reduction may have been a result of the decrease of crime across America and other factors like the 39% drop in NYC's unemployment rate.[19]

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Similar success occurred in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the late 1990s with its Safe Streets Program. Operating under the theory that American Westerners use roadways much in the same way that American Easterners use subways, the developers of the program reasoned that lawlessness on the roadways had much the same effect as it did in New York subways. Effects of the program were extensively reviewed by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and published in a case study.[20]

Lowell, Massachusetts

In 2005, Harvard University and Suffolk University researchers worked with local police to identify 34 "crime hot spots" in Lowell, Massachusetts. In half of the spots, authorities cleared trash, fixed streetlights, enforced building codes, discouraged loiterers, made more misdemeanor arrests, and expanded mental health services and aid for the homeless. In the other half of the identified locations, there was no change to routine police service.

The areas that received additional attention experienced a 20% reduction in calls to the police. The study concluded that cleaning up the physical environment is more effective than misdemeanor arrests, and that increasing social services had no effect.[21][22]

The Netherlands

In 2007 and 2008, Kees Keizer and colleagues from the University of Groningen conducted a series of controlled experiments to determine if the effect of existing visible disorder (such as litter or graffiti) increased other crime such as theft, littering, or other antisocial behavior. They selected several urban locations, which they arranged in two different ways, at different times. In one condition—the control—the place was maintained orderly and kept free from graffiti, broken windows, etc. In the other condition—the experiment—exactly the same environment was arranged to look as if nobody monitored it and cared about it: windows were broken and graffiti painted on the walls, among other things. The researchers then secretly monitored the locations to observe if people behaved differently when the environment was disordered. Their observations supported the theory, and they published their conclusion in the journal Science:

One example of disorder, like graffiti or littering, can indeed encourage another, like stealing.[23][24]

Other advantages

Real estate

Other side effects of better monitoring and cleaned up streets may well be desired by governments or housing agencies, as well as the population of a neighborhood: broken windows can count as an indicator of low real estate value, and may deter investors. Fixing windows is therefore also a step of real estate development, which may lead, desired or not, to gentrification. By reducing the amount of broken windows in the community, the inner cities would appear to be attractive to consumers with more capital. Ridding spaces like downtown New York and Chicago - notably notorious for criminal activity – of danger would draw in investment from consumers, increasing the city's economic status, providing a safe and pleasant image for present and future inhabitants.[25]

Schools

In the education realm, the broken windows theory is used to promote order in classrooms and school cultures. The belief is that students are signaled by disorder or rule-breaking and that they, in turn, imitate the disorder. Several school movements encourage strict paternalistic practices to enforce student discipline. Such practices include language codes (governing slang, curse words, or speaking out of turn), classroom etiquette (sitting up straight, tracking the speaker), personal dress (uniforms, little or no jewelry), and behavioral codes (walking in lines, specified bathroom times). Several schools have made remarkable strides in educational gains with this philosophy such as KIPP and American Indian Public Charter School.

From 2004 to 2006, Stephen B. Plank and colleagues from Johns Hopkins University conducted a correlational study to determine the degree to which the physical appearance of the school and classroom setting influence student behavior, particularly in respect to the variables concerned in their study: fear, social disorder, and collective efficacy.[26] They collected survey data administered to 6th-8th students by 33 public schools in a large mid-Atlantic city. From analyses of the survey data, the researchers determined that the variables concerning their study are statistically significant to the physical conditions of the school and classroom setting. Their conclusion, published in the American Journal of Education, was that:

...the findings of the current study suggest that educators and researchers should be vigilant about factors that influence student perceptions of climate and safety. Fixing broken windows and attending to the physical appearance of a school cannot alone guarantee productive teaching and learning, but ignoring them likely greatly increases the chances of a troubling downward spiral.[26]

Criticism of the theory

Other factors

Many critics state that there are factors, other than physical disorder, that more significantly influence crime rate. They argue that efforts to more effectively reduce crime rate should target or pay more attention to these factors instead.

According to a study by Robert J. Sampson and Stephen W. Raudenbush, the premise that the broken windows theory operates on—that social disorder and crime are connected as part of a causal chain—is faulty. They argue that a third factor, collective efficacy, “defined as cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space,” is the actual cause of varying crime rates that are observed in an altered neighborhood environment. They also argue that the relationship between public disorder and crime rate is weak.[27]

C. R. Sridhar, in his article in the Economic and Political Weekly, also challenges the broken windows policing and the notion introduced in the annotated by Kelling and Bratton—that aggressive policing, such as the “zero tolerance” police strategy adopted by William Bratton, the appointed commissioner of the New York Police Department—is the sole cause of the decrease of crime rates in New York City.[28] This policy targeted people in areas with a significant amount of physical disorder and there appeared to be a causal relationship between the adoption of the aggressive policy and the decrease in crime rate. Sridhar, however, discusses other trends (such as New York City's economic boom in the late 1990s) that created a "perfect storm"—that they all contributed to the decrease of crime rate much more significantly than the application of the zero tolerance policy. Sridhar also compares this decrease of crime rate with other major cities that adopted other various policies, and determined that the zero tolerance policy is not as effectual.

Baltimore criminologist Ralph B. Taylor argues in his book that fixing windows is only partial and short-term solution. His data supports a materialist view: changes in levels of physical decay, superficial social disorder, and racial composition do not lead to higher crime, while economic decline does. He contends that the example shows that real, long-term reductions in crime require that urban politicians, businesses, and community leaders work together to improve the economic fortunes of residents in high-crime areas.[29]

Another tack was taken by a 2010 study questioning the legitimacy of the theory concerning the subjectivity of disorder as perceived by persons living in neighborhoods. It concentrated on whether citizens view disorder as a separate issue from crime or as identical to it. The study noted that crime cannot be the result of disorder if the two are identical, agreed that disorder provided evidence of "convergent validity", and concluded that broken windows theory misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime.[30]

In recent years there has been increasing attention on the correlation between environmental lead levels and crime. Specifically, there appears to be a correlation with a 25-year lag with the addition and removal of lead from paint and gasoline and rises and falls in murder arrests.[31][32]

Implicit bias

RJ Sampson argues that based on common misconceptions by the masses, it is clearly implied that those who commit disorder and crime have a clear tie to groups suffering from financial instability and may be of minority status: "The use of racial context to encode disorder does not necessarily mean that people are racially prejudiced in the sense of personal hostility" and notes that residents make a clear implication of who they believe is causing the disruption, which has been termed as implicit bias.[33] He further states that research conducted on implicit bias and stereotyping of cultures suggests that community members hold unrelenting beliefs of African Americans and disadvantaged minority groups, associating them with crime, violence, disorder, welfare, and undesirability as neighbors.[33] A later study indicated that this contradicted Wilson and Kelling's proposition that disorder is an exogenous construct that has independent effects on how people feel about their neighborhoods.[30]

Criminology

According to most criminologists who speak of a broader "backlash",[lower-alpha 1] the broken windows theory is not theoretically sound.[34] They claim that the "broken windows theory" closely relates correlation with causality, a reasoning prone to fallacy. David Thacher, assistant professor of public policy and urban planning at the University of Michigan, stated in a 2004 paper that:[34]

[S]ocial science has not been kind to the broken windows theory. A number of scholars reanalyzed the initial studies that appeared to support it... Others pressed forward with new, more sophisticated studies of the relationship between disorder and crime. The most prominent among them concluded that the relationship between disorder and serious crime is modest, and even that relationship is largely an artifact of more fundamental social forces.

It has also been argued that rates of major crimes also dropped in many other U.S. cities during the 1990s, both those that had adopted "zero-tolerance" policies and those that had not.[35] In the Winter 2006 edition of the University of Chicago Law Review, Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig looked at the later Department of Housing and Urban Development program that re-housed inner-city project tenants in New York into more orderly neighborhoods.[36] The broken windows theory would suggest that these tenants would commit less crime once moved, due to the more stable conditions on the streets. Harcourt and Ludwig found instead that the tenants continued to commit crime at the same rate.

In a 2007 study called "Reefer Madness" in the journal Criminology and Public Policy, Harcourt and Ludwig found further evidence confirming that mean reversion fully explained the changes in crime rates in the different precincts in New York during the 1990s. Further alternative explanations that have been put forward include the waning of the crack epidemic,[37] unrelated growth in the prison population due to Rockefeller drug laws,[37] and that the number of males aged 16–24 was dropping regardless due to the shape of the US population pyramid.[38]

Drawbacks in practice

A low-level intervention of police in neighborhoods has been considered problematic. Accordingly, Gary Stewart writes that "The central drawback of the approaches advanced by Wilson, Kelling, and Kennedy rests in their shared blindness to the potentially harmful impact of broad police discretion on minority communities."[39] This was seen by the authors, who worried that people would be arrested "for the 'crime' of being undesirable". According to Stewart, arguments for low-level police intervention, including the broken windows hypothesis, often act "as cover for racist behavior".[39]

The application of the broken windows theory in aggressive policing policies, such as William J. Bratton's zero-tolerance policy, has been shown to criminalize the poor and homeless. This is because the physical signs that characterize a neighborhood with the “disorder” that broken windows policing targets correlate with the socio-economic conditions of its inhabitants. Many of the acts that are considered legal, but “disorderly” are often targeted in public settings and are not targeted when conducted in private. Therefore, those without access to a private space are often criminalized. Critics such as Robert J. Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush of Harvard University see the application of the broken windows theory in policing as a war against the poor as opposed to a war against more serious crimes.[40]

In Dorothy Roberts' article, "Foreword: Race, Vagueness, and the Social Meaning of Order Maintenance and Policing," she focuses on problems of the application of the broken windows theory that lead to the criminalization of communities of color, who are typically disfranchised.[41] She underscores the dangers of vaguely written ordinances that allows for law enforcers to determine who engages in disorderly acts, which in turn produce a racially skewed outcome in crime statistics.[42]

According to Bruce D. Johnson, Andrew Golub, and James McCabe, the application of the broken windows theory in policing and policy-making can result in development projects that decrease physical disorder but promote undesired gentrification. Often, when a city is “improved” in this way, the development of an area can cause the cost of living to rise higher than residents can afford, thus forcing low income people, often minorities, out of the area. As the space changes, middle- and upper class, often white, people begin to move into the area, resulting in the gentrification of urban, low income areas. The local residents are affected negatively by this application of the broken windows theory, ending up evicted from their homes as if their presence indirectly contributed to the area’s problem of “physical disorder”.[41]

In popular press

In the best-seller More Guns, Less Crime (University of Chicago Press, 2000), economist John Lott, Jr. examined the use of the broken windows approach as well as community- and problem-oriented policing programs in cities over 10,000 in population over two decades. He found that the impacts of these policing policies were not very consistent across different types of crime. Lott's book has been subject to criticism, though other groups support Lott's conclusions.

In the best-seller Freakonomics, economist Steven D. Levitt and co-author Stephen J. Dubner both confirm and cast doubt on the notion that the broken windows theory was responsible for New York's drop in crime, arguing "the reality that the pool of potential criminals had dramatically shrunk", an alternative that Levitt had attributed in the Quarterly Journal of Economics to the legalization of abortion with Roe v. Wade, a decrease in the number of delinquents in the population-at-large one generation later.[43]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The term "backlash" refers to the wave of "tough-on-crime" policies in the U.S. beginning in the 1980s.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wilson & Kelling 1982.

- ↑ Kelling, George; Coles, Catherine, Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities, ISBN 0-684-83738-2.

- ↑ Newman, Oscar, Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design, ISBN 0-02-000750-7.

- ↑ Gladwell, The tipping point.

- 1 2 Garland 2001.

- ↑ Wilcox et al. 2004, p. 186.

- ↑ Wilcox et al. 2004, p. 187.

- ↑ Jacobs 1961.

- ↑ Sampson & Raudenbush 2004, p. 319.

- ↑ Ranasinghe 2012, p. 65.

- ↑ Ranasinghe 2012, p. 67.

- ↑ Ranasinghe 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Jacobs 1961, p. 378.

- ↑ Ranasinghe 2012, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 Herbert & Brown 2006.

- 1 2 Adams, Joan (2006), The "Broken Windows" Theory, CA: UBC, (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Corman, Hope (Jun 2002), Carrots, Sticks and Broken Windows (PDF), Washington, (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Ludwig, Jens (2006), Broken windows (PDF), U Chicago.

- ↑ "Criticism for Giuliani’s broken windows theory", Business insider, Aug 2013.

- ↑ Albuquerque Police Department's Safe streets program, US: Department of Transportation – NHTSA, DOT HS 809 278.

- ↑ "Research Boosts Broken Windows". Suffolk University. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ↑ Johnson, Carolyn Y (2009-02-08). "Breakthrough on 'broken windows’". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ↑ Keizer, K; Lindenberg, S; Steg, L (2008). "The Spreading of Disorder". Science 322 (5908): 1681–5. doi:10.1126/science.1161405. PMID 19023045. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ↑ "Can the can". The Economist. 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Harcourt, Bernard L; Ludwig, Jens. "Broken Windows: New Evidence from New York City and a Five-City Social Experiment" (PDF).

- 1 2 Plank, Stephen B; Bradshaw, Catherine P; Young, Hollie (1 February 2009). "An Application of "Broken‐Windows" and Related Theories to the Study of Disorder, Fear, and Collective Efficacy in Schools". American Journal of Education 115 (2): 227–47. doi:10.1086/595669.

- ↑ Sampson, Robert J.; Raudenbush, Stephen W (1 November 1999). "Systematic Social Observation of Public Spaces: A New Look at Disorder in Urban Neighborhoods". American Journal of Sociology 105 (3): 603–51. doi:10.1086/210356.

- ↑ Sridhar, C.R. (13–19 May 2006). "Broken Windows and Zero Tolerance: Policing Urban Crimes". Economic and Political Weekly 41 (19): 1841–43.

- ↑ Ralph B. Taylor. Breaking Away from Broken Windows: Baltimore Neighborhoods and the Nationwide Fight Against Crime, Grime, Fear, and Decline. ISBN 0813397588

- 1 2 Gau & Pratt 2010.

- ↑ Lucifer Curves, Rick Nevin, 22 Feb 2015

- ↑ America's Real Criminal Element: Lead, Mother Jones, January/February 2013 Issue, Kevin Drum

- 1 2 Sampson & Raudenbush 2004, p. 320.

- 1 2 Thacher, David (2004). "Order Maintenance Reconsidered: Moving beyond Strong Causal Reasoning" (PDF). Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (Northwestern University School of Law) 94 (2). doi:10.2307/3491374.

- ↑ Harcourt, Bernard E (2001), Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing, Harvard, ISBN 0-674-01590-8.

- ↑ Harcourt, Bernard E; Ludwig, Jens (2006). "Broken Windows: New Evidence from New York City and a Five-City Social Experiment". University of Chicago Law Review 73.

- 1 2 Metcalf, Stephen. "The Giuliani Presidency? A new documentary makes the case against the outsized mayor". Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ↑ Levitt, Steven D.; Dubner, Stephen J (2005). Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-073132-X.

- 1 2 Stewart 1998.

- ↑ Sampson & Raudenbush 2004.

- 1 2 Johnson, Bruce D.; Golub, Andrew; McCabe, James (1 February 2010). "The international implications of quality‐of‐life policing as practiced in New York City". Police Practice and Research 11 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1080/15614260802586368.

- ↑ Roberts, Dorothy (Spring 1999). "Foreword: Race, Vagueness, and the Social Meaning of Order-Maintenance Policing". The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 3 89: 775–836. doi:10.2307/1144123.

- ↑ Donohue; Levitt (2001), The impact of legalized abortion (PDF), U Chicago.

Bibliography

- Garland, D (2001), The Culture of Control: Crime and Order in Contemporary Society, Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Herbert, Steve; Brown, Elizabeth (September 2006), "Conceptions of Space and Crime in the Punitive Neoliberal City", Antipode 38 (4): 755–77, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00475.x.

- Jacobs, J (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Vintage Books.

- Ranasinghe, P (2012), "Jane Jacobs' framing of public disorder and its relation to the 'broken windows' theory", Theoretical Criminology 16 (1): 63–84, doi:10.1177/1362480611406947.

- Sampson, RJ; Raudenbush, SW (2004), "Seeing Disorder: Neighborhood Stigma and the Social Construction of "Broken Windows"", Social Psychology Quarterly 67 (4): 319–42, doi:10.1177/019027250406700401.

- Stewart, Gary (May 1998), "Black Codes and Broken Windows: The Legacy of Racial Hegemony in Anti-Gang Civil Injunctions", The Yale Law Journal 107 (7): 2249–79, doi:10.2307/797421.

- Wilcox, P; Quisenberry, N; Cabrera, DT; Jones, S (2004), "Busy places & broken windows?: Toward Defining the Role of Physical Structure and Process in Community Crime Models", Sociological Quarterly 45 (2): 185–207, doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb00009.x.

- Wilson, James Q; Kelling, George L (Mar 1982), "Broken Windows: The police and neighborhood safety", The Atlantic, retrieved 2007-09-03 (Broken windows (PDF), Manhattan institute).

Further reading

- Bratton, William J (1998), Turnaround: How America's Top Cop Reversed the Crime Epidemic, Random House.

- Eck, John E; Maguire, Edward R (2006), "Have Changes in Policing Reduced Violent Crime?", in Blumstein, Alfred; Wallman, Joel, The Crime Drop in America (rev ed.), Cambridge University Press.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (2002), The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Back Bay, ISBN 0-316-34662-4.

- Silman, Eli B (1999), NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Strategies in Policing, Northeastern University Press.

- Skogan, Wesley G (1990), Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods, University of California Press.

External links

- "Debate club", Legal Affairs

|contribution=ignored (help) – a review of the criticisms of the broken windows theory. - Shattering "Broken Windows": An Analysis of San Francisco's Alternative Crime Policies (PDF) (article), Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, detailing crime reduction in San Francisco achieved via alternative crime policies.

- Community Policing Defined (PDF), US: Department of Justice, an article explaining the philosophy and method of community policing.

.svg.png)