Bread

|

Various leavened breads | |

| Main ingredients | Flour, water |

|---|---|

|

| |

Bread is a staple food prepared from a dough of flour and water, usually by baking. Throughout recorded history it has been popular around the world and is one of the oldest artificial foods, having been of importance since the dawn of agriculture.

There are many combinations and proportions of types of flour and other ingredients, and also of different traditional recipes and modes of preparation of bread. As a result, there are wide varieties of types, shapes, sizes, and textures of breads in various regions. Bread may be leavened by many different processes ranging from the use of naturally occurring microbes (for example in sourdough recipes) to high-pressure artificial aeration methods during preparation or baking. However, some products are left unleavened, either for preference, or for traditional or religious reasons. Many non-cereal ingredients may be included, ranging from fruits and nuts to various fats. Commercial bread in particular, commonly contains additives, some of them non-nutritional, to improve flavor, texture, color, shelf life, or ease of manufacturing.

Depending on local custom and convenience, bread may be served in various forms at any meal of the day. It also is eaten as a snack, or used as an ingredient in other culinary preparations, such as fried items coated in crumbs to prevent sticking, or the bland main component of a bread pudding, or stuffings designed to fill cavities or retain juices that otherwise might drip away.

Partly because of its importance as a basic foodstuff, bread has a social and emotional significance beyond its importance in nutrition; it plays essential roles in religious rituals and secular culture. Its prominence in daily life is reflected in language, where it appears in proverbs, colloquial expressions ("He stole the bread from my mouth"), in prayer ("Give us this day our daily bread") and even in the etymology of words, such as "companion" and "company" (literally those who eat/share bread with you).

Etymology

The word itself, Old English bread, is most common in various forms to many Germanic languages, such as Frisian brea, Dutch brood, German Brot, Swedish bröd, and Norwegian and Danish brød; it has been claimed to be derived from the root of brew. It may be connected with the root of break, for its early uses are confined to broken pieces or bits of bread, the Latin crustum, and it was not until the 12th century that it took the place—as the generic name for bread—of hlaf (hlaifs in Gothic: modern English loaf), which appears to be the oldest Teutonic name.[1] Old High German hleib[2] and modern German Laib derive from this Proto-Germanic word for "loaf", which was borrowed into Slavic (Polish chleb, Russian khleb) and Finnic (Finnish leipä, Estonian leib) languages as well.

In many cultures, bread is a metaphor for basic necessities and living conditions in general. For example, a "bread-winner" is a household's main economic contributor and has little to do with actual bread-provision. This is also seen in the phrase "putting bread on the table". The Roman poet Juvenal satirized superficial politicians and the public as caring only for "panem et circenses" (bread and circuses). In Russia in 1917, the Bolsheviks promised "peace, land, and bread."[3][4] The term "breadbasket" denotes an agriculturally productive region. In Slavic cultures bread and salt is offered as a welcome to guests. In India, life's basic necessities are often referred to as "roti, kapra aur makan" (bread, cloth, and house). In Israel, the most usual phrase in work-related demonstrations is lekhem, avoda ("bread, work").

The word bread is commonly used around the world in English-speaking countries as a synonym for money[1] (as is the case with the word "dough"). A remarkable or revolutionary innovation is often referred to in North America and the United Kingdom as "the greatest thing since sliced bread" or "the best thing since sliced bread".

History

Bread is one of the oldest prepared foods. Evidence from 30,000 years ago in Europe revealed starch residue on rocks used for pounding plants.[5] It is possible that during this time, starch extract from the roots of plants, such as cattails and ferns, was spread on a flat rock, placed over a fire and cooked into a primitive form of flatbread. Around 10,000 BC, with the dawn of the Neolithic age and the spread of agriculture, grains became the mainstay of making bread. Yeast spores are ubiquitous, including the surface of cereal grains, so any dough left to rest will become naturally leavened.[6]

There were multiple sources of leavening available for early bread. Airborne yeasts could be harnessed by leaving uncooked dough exposed to air for some time before cooking. Pliny the Elder reported that the Gauls and Iberians used the foam skimmed from beer to produce "a lighter kind of bread than other peoples." Parts of the ancient world that drank wine instead of beer used a paste composed of grape juice and flour that was allowed to begin fermenting, or wheat bran steeped in wine, as a source for yeast. The most common source of leavening was to retain a piece of dough from the previous day to use as a form of sourdough starter.[7]

In 1961 the Chorleywood bread process was developed, which used the intense mechanical working of dough to dramatically reduce the fermentation period and the time taken to produce a loaf. The process, whose high-energy mixing allows for the use of lower protein grain, is now widely used around the world in large factories. As a result, bread can be produced very quickly and at low costs to the manufacturer and the consumer. However, there has been some criticism of the effect on nutritional value.[8]

Recently, domestic bread machines that automate the process of making bread have become popular.

Types

Bread is the staple food of the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and in European-derived cultures such as those in the Americas, Australia, and Southern Africa, in contrast to East Asia where rice is the staple. Bread is usually made from a wheat-flour dough that is cultured with yeast, allowed to rise, and finally baked in an oven. Owing to its high levels of gluten (which give the dough sponginess and elasticity), common wheat (also known as bread wheat) is the most common grain used for the preparation of bread.

Bread is also made from the flour of other wheat species (including durum, spelt and emmer), rye, barley, maize (corn), and oats, usually, but not always, in combination with wheat flour. Spelt bread (Dinkelbrot) continues to be widely consumed in Germany, and emmer bread was a staple food in ancient Egypt. Canadian bread is known for its heartier consistency due to high protein levels in Canadian flour.

- Pita is an ancient semi-leavened bread widespread in the Middle East, Levant and South Eastern Europe.

- White bread is made from flour containing only the central core of the grain (endosperm).

- Brown bread is made with endosperm and 10% bran. It can also refer to white bread with added coloring (often caramel) to make it brown; this is commonly labeled in America as wheat bread (as opposed to whole-wheat bread).[9]

- Wholemeal bread contains the whole of the wheat grain (endosperm, bran, and germ). It is also referred to as "whole-grain" or "whole-wheat bread", especially in North America.

- Wheat germ bread has added wheat germ for flavoring.

- Whole-grain bread can refer to the same as wholemeal bread, or to white bread with added whole grains to increase its fibre content, as in "60% whole-grain bread".

- Roti is a whole-wheat-based bread eaten in South Asia. Chapatti is a type of roti. Naan is a leavened equivalent to these.

- Granary bread (a registered trademark, owned by Rank Hovis[10]) is made from flaked wheat grains and white or brown flour. The standard malting process is modified to maximise the maltose or sugar content but minimise residual alpha amylase content. Other flavor components are imparted from partial fermentation due to the particular malting process used and to Maillard reactions on flaking and toasting.

- Rye bread is made with flour from rye grain of varying levels. It is higher in fiber than many common types of bread and is often darker in color and stronger in flavor. It is popular in Scandinavia, Germany, Finland, the Baltic States, and Russia.

- Unleavened bread or matzo, used for the Jewish feast of Passover, does not include yeast, so it does not rise.

- Sourdough bread is made with a starter.

- Flatbread is often simple, made with flour, water, and salt, and then formed into flattened dough; most are unleavened, made without yeast or sourdough culture, though some are made with yeast.

- Crisp bread is a flat and dry type of bread or cracker, containing mostly rye flour.

- Hemp bread includes strongly flavored hemp flour or seeds. Hemp has been used for thousands of years in traditional Chinese medicine.[11] Hemp flour is the by-product from pressing the oil from the seeds and milling the residue. It is perishable and stores best in the freezer. Hemp dough won't rise due to its lack of gluten, and for that reason it is best mixed with other flours. A 5:1 ratio of wheat-to-hemp flour produces a hearty, nutritious loaf high in protein and essential fatty acids.[12] Hemp seeds have a relatively high oil content of 25–35%, and can be added at a rate up to 15% of the wheat flour. The oil's omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio lies in the range of 2:1-to-3:1, which is considered ideal for human nutrition.[13]

- Quick breads usually refers to a bread chemically leavened, usually with both baking powder and baking soda, and a balance of acidic ingredients and alkaline ingredients. Examples include pancakes and waffles, muffins and carrot cake, Boston brown bread, and zucchini and banana bread.

- Gluten-free breads have been created in recent years[14] due to the discovery that people affected by gluten-related disorders, such as coeliac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity sufferers, benefit from a gluten-free diet.[15][16][17] Gluten-free bread is made with ground flours from a variety of materials such as almonds, rice, sorghum, corn, or legumes such as beans, but since these flours lack gluten they may not hold their shape as they rise and their crumb may be dense with lttle aeration. Additives such as xanthum gum, guar gum, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), corn starch, or eggs are used to compensate for the lack of gluten.

Preparation

Doughs are usually baked, but in some cuisines breads are steamed (e.g., mantou), fried (e.g., puri), or baked on an unoiled frying pan (e.g., tortillas). It may be leavened or unleavened (e.g. matzo). Salt, fat and leavening agents such as yeast and baking soda are common ingredients, though bread may contain other ingredients, such as milk, egg, sugar, spice, fruit (such as raisins), vegetables (such as onion), nuts (such as walnuts) or seeds (such as poppy). Referred to colloquially as the "staff of life", bread has been prepared for at least 30,000 years. The development of leavened bread can probably also be traced to prehistoric times. Sometimes, the word bread refers to a sweetened loaf cake, often containing appealing ingredients like dried fruit, chocolate chips, nuts or spices, such as pumpkin bread, banana bread or gingerbread.

Fresh bread is prized for its taste, aroma, quality, appearance and texture. Retaining its freshness is important to keep it appetizing. Bread that has stiffened or dried past its prime is said to be stale. Modern bread is sometimes wrapped in paper or plastic film or stored in a container such as a breadbox to reduce drying. Bread that is kept in warm, moist environments is prone to the growth of mold. Bread kept at low temperatures, in a refrigerator for example, will develop mold growth more slowly than bread kept at room temperature, but will turn stale quickly due to retrogradation.

The soft, inner part of bread is known to bakers and other culinary professionals as the crumb, which is not to be confused with small bits of bread that often fall off, called crumbs. The outer hard portion of bread is called the crust. The crumb's texture is greatly determined by the quality of the pores in the bread.

Formulation

Professional baker recipes are stated using a notation called baker's percentage. The amount of flour is denoted to be 100%, and the amounts of the other ingredients are expressed as a percentage of that amount by weight. Measurement by weight is more accurate and consistent than measurement by volume, particularly for dry ingredients.

The proportion of water to flour is the most important measurement in a bread recipe, as it affects texture and crumb the most. Hard US wheat flours absorb about 62% water, while softer wheat flours absorb about 56%.[18] Common table breads made from these doughs result in a finely textured, light bread. Most artisan bread formulas contain anywhere from 60 to 75% water. In yeast breads, the higher water percentages result in more CO2 bubbles and a coarser bread crumb. One pound (450 g) of flour will yield a standard loaf of bread or two French loaves.

Calcium propionate is commonly added by commercial bakeries to retard the growth of molds.

Flour

Flour is a product made from grain that has been ground to a powdery consistency. Flour provides the primary structure to the final baked bread. While wheat flour is most commonly used for breads, flours made from rye, barley, maize, and other grains are also commonly available. Each of these grains provides the starch and protein needed to form bread.

The protein content of the flour is the best indicator of the quality of the bread dough and the finished bread. While bread can be made from all-purpose wheat flour, a specialty bread flour, containing more protein (12–14%), is recommended for high-quality bread. If one uses a flour with a lower protein content (9–11%) to produce bread, a shorter mixing time will be required to develop gluten strength properly. An extended mixing time leads to oxidization of the dough, which gives the finished product a whiter crumb, instead of the cream color preferred by most artisan bakers.[19]

Wheat flour, in addition to its starch, contains three water-soluble protein groups (albumin, globulin, and proteoses) and two water-insoluble protein groups (glutenin and gliadin). When flour is mixed with water, the water-soluble proteins dissolve, leaving the glutenin and gliadin to form the structure of the resulting bread. When relatively dry dough is worked by kneading, or wet dough is allowed to rise for a long time (see no-knead bread), the glutenin forms strands of long, thin, chainlike molecules, while the shorter gliadin forms bridges between the strands of glutenin. The resulting networks of strands produced by these two proteins are known as gluten. Gluten development improves if the dough is allowed to autolyse.

Liquids

Water, or some other liquid, is used to form the flour into a paste or dough. The weight of liquid required varies between recipes, but a ratio of 3 parts liquid to 5 parts flour is common for yeast breads.[20] Recipes that use steam as the primary leavening method may have a liquid content in excess of 1 part liquid to 1 part flour. Instead of water, other types of liquids, such as dairy products, fruit juices, or beer, may be used; they contribute additional sweeteners, fats, or leavening components, as well as water.

Leavening

Leavening is the process of adding gas to a dough before or during baking to produce a lighter, more easily chewed bread. Most bread consumed in the West is leavened. Unleavened breads have symbolic importance in Judaism and Christianity: Jews consume unleavened bread called matzo during Passover, and Roman Catholic and some Protestant Christians consume unleavened sacramental bread when celebrating the Eucharist, a rite derived from the narrative of the Last Supper when Jesus broke bread with his disciples, perhaps during a Passover Seder. In contrast, Orthodox Christians always use leavened bread during their liturgy.

Chemical leavening

A simple technique for leavening bread is the use of gas-producing chemicals. There are two common methods. The first is to use baking powder or a self-rising flour that includes baking powder. The second is to include an acidic ingredient such as buttermilk and add baking soda; the reaction of the acid with the soda produces gas.

Chemically leavened breads are called quick breads and soda breads. This method is commonly used to make muffins, pancakes, American-style biscuits, and quick breads such as banana bread.

Yeast

Many breads are leavened by yeast. The yeast most commonly used for leavening bread is Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the same species used for brewing alcoholic beverages. This yeast ferments some of the carbohydrates in the flour, including any sugar, producing carbon dioxide. Most bakers in the U.S. leaven their dough with commercially produced baker's yeast. Baker's yeast has the advantage of producing uniform, quick, and reliable results, because it is obtained from a pure culture. Many artisan bakers produce their own yeast by preparing a growth culture that they then use in the making of bread. When this culture is kept in the right conditions, it will continue to grow and provide leavening for many years.

Both the baker's yeast and the sourdough methods of baking bread follow the same pattern. Water is mixed with flour, salt and the leavening agent (baker's yeast or sourdough starter). Other additions (spices, herbs, fats, seeds, fruit, etc.) are not needed to bake bread, but are often used. The mixed dough is then allowed to rise one or more times (a longer rising time results in more flavor, so bakers often "punch down" the dough and let it rise again), then loaves are formed, and (after an optional final rising time) the bread is baked in an oven.

Many breads are made from a "straight dough", which means that all of the ingredients are combined in one step, and the dough is baked after the rising time; others are made from a "pre-ferment" in which the leavening agent is combined with some of the flour and water a day or so ahead of baking and allowed to ferment overnight. On the day of the baking, the rest of the ingredients are added, and process continues as with straight dough. This produces a more flavorful bread with better texture.

Many bakers see the starter method as a compromise between the highly reliable results of baker's yeast and the flavor and complexity of a longer fermentation. It also allows the baker to use only a minimal amount of baker's yeast, which was scarce and expensive when it first became available. Most yeasted pre-ferments fall into one of three categories: "poolish" or "pouliche", a loose-textured mixture composed of roughly equal amounts of flour and water (by weight); "biga", a stiff mixture with a higher proportion of flour; and "pâte fermentée", which is simply a portion of dough reserved from a previous batch. Sourdough (also known as "levain" or "natural leaven") takes the pre-ferment method a step further, mixing flour and water to allow naturally occurring yeast and bacteria to propagate (usually Saccharomyces exiguus, which is more acid-tolerant than S. cerevisiae and various species of Lactobacillus).

|

|

|

| Dough before first rising. | Dough after first rising. | Dough after proofing in tin, ready to bake. |

Sourdough

Sourdough is a type of bread produced by a long fermentation of dough using naturally occurring yeasts and lactobacilli. In comparison with breads made with cultivated yeast, it usually has a mildly sour taste because of the lactic acid produced by the lactobacilli.

Sourdough breads are made with a sourdough starter (which differs from starters made with baker's yeast). The starter cultivates yeast and lactobacilli in a mixture of flour and water, making use of the microorganisms already present on flour; it does not need any added yeast. A starter may be maintained indefinitely by regular additions of flour and water. Some bakers have starters several generations old, which are said to have a special taste or texture. It is possible to obtain existing starter cultures to begin a new one.

At one time, all yeast-leavened breads were sourdoughs. The leavening process was not understood until the 19th century, when yeast was first identified. Since then, strains of Saccaromyces cerevisiae have been bred for their reliability and speed of leavening and sold as "baker's yeast". Baker's yeast was adopted for the simpicity and flexibility it introduced to bread making, obviating the lengthy cultivation of a sourdough starter. While sourdough breads survived in some parts of Europe, throughout most of the U.S., they were replaced by baker's yeast. Recently there has been a revival of sourdough bread in artisan bakeries.

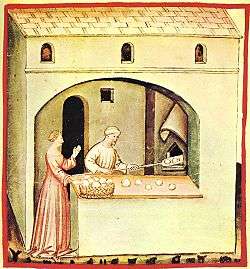

There are other ways of sourdough baking and culture maintenance. A more traditional one is the process that was followed by peasant families throughout Europe in past centuries. The family (usually the woman was in charge of breadmaking) would bake on a fixed schedule, perhaps once a week. The starter was saved from the previous week's dough. The starter was mixed with the new ingredients, the dough was left to rise, and then a piece of it was saved (to be the starter for next week's bread). The rest was formed into loaves that were marked with the family sign (this is where today's decorative slashing of bread loaves originates from) and taken to the communal oven to bake. These communal ovens with time evolved into the modern bakery.

Steam

The rapid expansion of steam produced during baking leavens the bread, which is as simple as it is unpredictable. The best known steam-leavened bread is the popover. Steam-leavening is unpredictable since the steam is not produced until the bread is baked.

Steam leavening happens regardless of the rising agents (baking soda, yeast, baking powder, sour dough, beaten egg whites, etc.).

- The leavening agent either contains air bubbles or generates carbon dioxide.

- The heat vaporises the water from the inner surface of the bubbles within the dough.

- The steam expands and makes the bread rise.

This is the main factor in the rise of bread once it has been put in the oven.[21] CO2 generation, on its own, is too small to account for the rise. Heat kills bacteria or yeast at an early stage, so the CO2 generation is stopped.

Bacteria

Salt-rising bread employs a form of bacterial leavening that does not require yeast. Although the leavening action is not always consistent, and requires close attention to the incubating conditions, this bread is making a comeback due to its unique cheese-like flavor and fine texture.[22]

Aeration

Aerated bread is leavened by carbon dioxide being forced into dough under pressure. From the mid 19th to 20th centuries bread made this way was somewhat popular in the United Kingdom, made by the Aerated Bread Company and sold in its high-street tearooms. The company was founded in 1862, and ceased independent operations in 1955. While it had some devoted adherents, it never eclipsed the use of baker's yeast worldwide.

The Pressure-Vacuum mixer was later developed by the Flour Milling and Baking Research Association at Chorleywood. With the application of both pressure and vacuum at different points in the mixing process, this mixer not only manipulates the gas bubble size, it may also manipulate the composition of gases in the dough via the gas applied to the headspace.[23]

Fats or shortenings

Fats, such as butter, vegetable oils, lard, or that contained in eggs, affect the development of gluten in breads by coating and lubricating the individual strands of protein. They also help to hold the structure together. If too much fat is included in a bread dough, the lubrication effect will cause the protein structures to divide. A fat content of approximately 3% by weight is the concentration that will produce the greatest leavening action.[24] In addition to their effects on leavening, fats also serve to tenderize breads and preserve freshness.

Bread improvers

Bread improvers and dough conditioners are often used in producing commercial breads to reduce the time needed for rising and to improve texture and volume. Chemical substances commonly used as bread improvers include ascorbic acid, hydrochloride, sodium metabisulfate, ammonium chloride, various phosphates, amylase, and protease.

Salt is one of the most common additives used in production. In addition to enhancing flavor and restricting yeast activity, salt affects the crumb and the overall texture by stabilizing and strengthening[25] the gluten. Some artisan bakers are foregoing early addition of salt to the dough, and are waiting until after a 20-minute "rest". This is known as an autolyse[26] and is done with both refined and whole-grain flours.

Properties

Chemical composition

In wheat, phenolic compounds are mainly found in hulls in the form of insoluble bound ferulic acid where it is relevant to wheat resistance to fungal diseases.[27]

Rye bread contains phenolic acids and ferulic acid dehydrodimers.[28]

Three natural phenolic glucosides, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, p-coumaric acid glucoside and ferulic acid glucoside, can be found in commercial breads containing flaxseed.[29]

Serving and consumption

Bread can be served at many temperatures; once baked, it can subsequently be toasted. It is most commonly eaten with the hands, either by itself or as a carrier for other foods. Bread can be dipped into liquids such as gravy, olive oil, or soup; it can be topped with various sweet and savory spreads, or used to make sandwiches containing myriad varieties of meats, cheeses, vegetables, and condiments.

Bread may also be used as an ingredient in other culinary preparations, such as the use of breadcrumbs to provide crunchy crusts or thicken sauces, sweet or savoury bread puddings, or as a binding agent in sausages and other ground meat products.

Nutritional significance

Nutritionally, bread is known as an ample source for the grains category of nutrition. Serving size of bread is standard through ounces, counting one slice of bread (white processed bread) as 1 oz. Also, bread is considered a good source of carbohydrates through the whole grains, nutrients such as magnesium, iron, selenium, B vitamins, and dietary fiber. As part of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans,[30] it is recommended to make at least half of the recommended total grain intake as whole grains and to overall increase whole grains intake.

Shelf life

In 2009, a natural preservative for extending the shelf life of bread for up to two weeks (as opposed to a few days) had been patented and licensed to Puratos, a Belgium-based baking ingredients company that supplies to more than 100 countries. The breakthrough was pioneered by Prof Elke Arendt at the University College Cork (UCC) by incorporating into the bread a lactic acid bacteria strain which also "produces a fine crumb texture" and "improves the flavour, volume and nutritional value of the food as well." Prior to this, "About 20% of all bread is thrown out due to shelf-life issues."[31]

Crust

The bread crust is formed from surface dough during the cooking process. It is hardened and browned through the Maillard reaction using the sugars and amino acids and the intense heat at the bread surface. The nature of a bread's crust differs depending on the type of bread and the way it is baked. Commercial bread is baked using jets that direct steam toward the bread to help produce a desirable crust.

The crust of most breads is less soft, and more complexly and intensely flavored, than the rest, and judgments vary among individuals and cultures as to whether it is therefore the less palatable or the more flavorful part of a particular style of bread. Some manufacturers, including as of September 2009 Sara Lee, market traditional and crustless breads.

The first and last slices of a loaf (or a slice with a high ratio of crust-area to volume compared to others of the same loaf) are sometimes referred to as the heel or the crust of the loaf.[32]

Old wives tales suggest that eating the bread crust makes a person's hair curlier. Additionally, the crust is rumored to be healthier than the rest. Some studies have shown that this is true as the crust has more dietary fiber and antioxidants, notably pronyl-lysine.[33][34] The pronyl-lysine found in bread crust is being researched for its potential colorectal cancer inhibitory properties.[35][36]

Cultural significance

Bread has a significance beyond mere nutrition in many cultures in the West and Near and Middle East because of its history and contemporary importance. Bread is also significant in Christianity as one of the elements (alongside wine) of the Eucharist; see sacramental bread. The word companion comes from Latin com- "with" + panis "bread".[37]

The political significance of bread is considerable. In 19th century Britain, the inflated price of bread due to the Corn Laws caused major political and social divisions, and was central to debates over free trade versus protectionism. The Assize of Bread and Ale in the 13th century demonstrated the importance of bread in medieval times by setting heavy punishments for short-changing bakers, and bread appeared in the Magna Carta a half-century earlier.

Like other foods, choosing the "right" kind of bread is used as a type of social signalling, to let others know, for example, that the person buying expensive bread is financially secure, or the person buying whatever type of bread that the current fashions deem most healthful is a health-conscious consumer.[38]

... bread has become an article of food of the first necessity; and properly so, for it constitutes of itself a complete life-sustainer, the gluten, starch, and sugar, which it contains, represents azotised and hydro-carbonated nutrients, and combining the sustaining powers of the animal and vegetable kingdoms in one product. Mrs Beeton (1861)[39]

As a simple, cheap, and adaptable type of food, bread is often used as a synecdoche for food in general in some languages and dialects, such as Greek and Punjabi. There are many variations on the basic recipe of bread worldwide, such as bagels, baguettes, biscuits, bocadillo, brioche, chapatis, lavash, naan, pitas, pizza, pretzels, puris, tortillas, and many others. There are various types of traditional "cheese breads" in many countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Italy, and Russia.

Asia

The traditional bread in China is mantou. It is made by steaming or deep-frying dough made from wheat flour. In Northern China and northern central China, mantou is often eaten as an alternative staple to rice. Steamed mantou is similar to Western white bread, but since it is not baked it does not have a brown outer crust. Mantou that have a filling such as meat or vegetables (cha siu bao, for example) are called baozi. The kompyang of Fuzhou is an example of a Chinese bread baked in a clay oven.

In South Asia (including India, Pakistan, and the Middle East), chapati or roti, types of unleavened flatbreads usually made from whole-wheat flour or sometimes refined wheat flour and baked on a hot iron griddle called a tava, form the mainstay of the people's diet. The Miracle Chapati, as it became known, is an unleavened bread with a long tradition. The bread can be spelled Chapathi, Chapati, Chapatti, or Chappati.[40] Rotis and naans are usually served with curry throughout the region. A variant called makki di roti uses maize flour rather than white flour. Another variant is puri, a thin flat bread that is fried rather than baked and puffs up while cooked. Paratha is another variation on roti. Naan (leavened wholewheat bread) is baked in a tandoor or clay oven and is rarely prepared at home. White and brown breads are also very common, but not as common as roti.

In the Philippines, pandesal (or pan de sal, meaning bread of salt or salt bread) is a rounded bread usually eaten by Filipinos during breakfast. The Philippines also produces a cheap generic white bread called Pinoy Tasty.[41][42]

Europe

An enormous variety of bread is available across Europe. Germany lays claim to over 1300 basic varieties of breads, rolls, and pastries, as well as having the largest consumption of bread per capita worldwide, followed by Chile.[43][44][45][46] Bread and salt is a welcome greeting ceremony in many central and eastern European cultures. During important occasions when guests arrive, they are offered a loaf of bread with a salt holder to represent hospitality.[47]

In France, there has been a huge decline in the baguette culture. In the 1970s, French people were consuming an average of one loaf of bread per day. Only a century ago, the French ate approximately 3 loaves of bread per day. Today, French people eat only a half a loaf of bread per day. In response to this decline, bakers have created a national campaign to get people to call at the bakery before and after work just as they used to. The campaign models the American "Got Milk?" campaign, plastering "Hey there, have you picked up the bread?" all over billboards and bread bags.[48]

There is a wide variety of traditional breads in Great Britain, often baked in a rectangular tin. Round loaves are also produced, such as the North East England specialty called a stottie cake. A cob is a small round loaf. A cottage loaf is made of two balls of dough, one on top of the other, to form a figure-of-eight shape. There are many variations on bread rolls, such as baps, barms, breadcakes and so on. The Chorleywood process for mass-producing bread was developed in England in the 1960s before spreading worldwide. Mass-produced sliced white bread brands such as Wonderloaf and Mother's Pride have been criticized on grounds of poor nutritional value and taste of the loaves produced.[49]

In Spain, bread is called pan. The traditional Spanish pan is a long loaf of bread, similar to the French baguette but wider. One can buy it freshly made every morning in the traditional bakeries, where there is a large assortment of bread. A smaller version is known as bocadillo, an iconic piece of the Hispanic cuisine. In Spain, especially in the Mediterranean area, there have been guilds of bakers for over 750 years. The bakers guild in Barcelona was founded in 1200 AD.[50] There is a region called Tierra del Pan ("Land of the Bread"), located in the province of Zamora, where economy was in the past joined to this activity.

Latin America

In Mexico, bread is called pan. Although corn tortillas are the staple bread in most of Mexico, bread rolls in many varieties are an important daily food for city dwellers. Popular breads in Mexico include the bolillo roll and pan dulce. Pan dulce, which is Spanish for "sweet bread", is eaten in the evenings with hot drinks like traditional hot chocolate.

In Peru, pan has many variations due to the diversity of Peruvian cuisine. People usually eat pan de piso and pan serrano. There are also some kinds of bread made of potatoes; these are currently popular in the Andes. Bizcochos are sweet bread usually eaten with some butter and hot chocolate. A dough made with cooked pumpkin or squash, often shaped and fried into doughnuts and served with a sweet fruity dipping sauce, is a traditional favorite. Bread is an ingredient of sopas de ajo, gazpacho, and salmorejo.

North Africa

In Ethiopia in east North Africa, a bread called injera is made from a grain called teff.[51] This is a wide, flat, circular bread that is in a similar shape of a tortilla and is also used as a utensil to pick up food.

Also consumed is a thick and chewy fried bread that is smothered in oil beforehand. The rghifa bread is a staple in the food of Morocco and consists of several layers of lightly cooked bread.

In Egypt, bread is called aysh (aish merahrah or aish baladi) and the ancient proverb has it that "life without aysh is not life". The typical Egyptian bread is circular, about 6 inches across, often baked in small neighbourhood bakeries and bought still warm.[52][53]

North America

Traditional breads in the United States include cornbreads and various quick breads, such as biscuits. Rolls, made from wheat flour and yeast, are another popular and traditional bread, eaten with the dinner meal.

Cornbread is made from cornmeal and can differ significantly in taste and texture from region to region. In general, the South prefers white cornmeal with little to no wheat flour or sweeteners added; it is traditionally baked in a cast-iron skillet and ideally has a crunchy outside and moist inside. The North usually prefers yellow cornmeal with sometimes as much as half wheat flour in its composition, as well as sugar, honey, or maple syrup. This results in a bread that is softer and sweeter than its southern counterpart. Wheat flour was not available to the average North American family until the early 1900s when a new breed of wheat termed Marquis was produced. This was a hybrid of Red Fife and Hard red winter wheat. Marquis grew well and soon average Americans were able to have homemade wheat bread on the table.[54] Homemade wheat breads are made in a rectangular tin similar to those in the United Kingdom.

Spoon bread, also called batter bread or egg bread, is made of cornmeal with or without added rice and hominy, and is mixed with milk, eggs, shortening and leavening to such a consistency that it must be served from the baking dish with a spoon. This is popular chiefly in the South.

Sourdough biscuits are traditional "cowboy food" in the West. The San Francisco Bay Area is known for its crusty sourdough.

Up until the 20th century (and even later in certain regions), any flour other than cornmeal was considered a luxury; this would explain the greater variety in cornbread types compared to that of wheat breads. In terms of commercial manufacture, the most popular bread has been a soft-textured type with a thin crust that is usually made with milk and is slightly sweet; this is the type that is generally sold ready-sliced in packages. It is usually eaten with the crust, but some eaters or preparers may remove the crust due to a personal preference or style of serving, as with finger sandwiches served with afternoon tea. Some of the softest bread, including Wonder Bread, is referred to as "balloon bread".

Though white "sandwich bread" is the most popular, Americans are trending toward more artisanal breads. Different regions of the country feature certain ethnic bread varieties including the Ashkenazi Jewish bagel, the French baguette, the Italian-style scali bread made in New England, Jewish rye, commonly associated with delicatessen cuisine, and Native American frybread (a product of hardship, developed during the Indian resettlements of the 19th century).

Religious significance

Abrahamic religions

During the Jewish festival of Passover, only unleavened bread is eaten, in commemoration of the flight from slavery in Egypt. The Israelites did not have enough time to allow their bread to rise, and so ate only unleavened bread (matzoh).[55]

In the Christian ritual of the Eucharist, bread symbolically represents the body of Christ, and is eaten as a sacrament.[56] Specific aspects of the ritual itself, including the composition of the bread, vary from denomination to denomination. The differences in the practice of the Eucharist stem from different descriptions and depictions of the Last Supper which provides the scriptural basis for the Eucharist.[57] The Synoptic Gospels present the Last Supper as a Passover meal and suggest that the bread at the Last Supper would be unleavened. However, in the chronology in Gospel of John, the Last Supper occurred the day before Passover suggesting that the bread would be leavened. Despite this point of disagreement, the Council of Florence of the Catholic church agreed that “the body of Christ is truly confected in both unleavened and leavened wheat bread, and priests should confect the body of Christ in either”.[58]

Paganism

Some traditions of Wicca and Neo-Paganism consume bread as part of their religious rituals, attaching varied symbolism to the act.[59]

Anti-bread movements

Although eaten by nearly all people, some have rejected bread entirely or rejected types of bread that they consider unhealthy. Reasons for doing so have varied through history: whole grain bread has been criticized as being unrefined, and white bread as being unhealthfully processed; homemade bread has been deemed unsanitary, and factory-made bread regarded with suspicion for being adulterated.[38] Amylophobia, literally "fear of starch", was a movement in the US during the 1920s and 1930s.[38]

In the United States, bread sales fell by 11.3% between 2008 and 2013. This statistic might reflect a change in the types of food from which Americans are getting their carbohydrates, but the trends are unclear because of differences between the markets for different classes of bread products.[60] It is also possible that changing diet fashions affected the decrease in bread sales during that period.[61]

In medicine

The ancient Egyptians used moldy bread to treat infections that arose from dirt in burn wounds.[62]

See also

- Breadmaking ingredients, techniques and tools

- Culinary uses

- Anadama bread

- Barley bread

- Beer bread

- Biscuit

- Bread roll

- Brioche

- Broa

- Brown bread

- Bun

- Bush bread

- Canadian White

- Cardamom bread

- Challah

- Chapati

- Cornbread

- Cottage loaf

- Damper

- Flatbread

- Focaccia

- Horsebread

- Indian bread

- Irish soda bread

- Ka'ak

- Lavash

- Mantou

- Matzo

- Melonpan

- Monkey bread

- Naan

- Pandoro

- Paratha

- Pashti

- Pita

- Portuguese sweet bread

- Potato bread

- Proja

- Pumpernickel

- Puri

- Rice bread

- Roti

- Rye bread

- Shotis puri

- Seed cakes

- Texas toast

- Tiger bread

- Tortilla

- White bread

- Whole-wheat bread

- Zopf

References

- 1 2 Harper, Douglas. "bread". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Diakonov, I. M. (1999). The paths of history. Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 0521643988.

Slavic langues retain many Gothic words, reflecting cultural borrowings: thus khleb, (bread) from an earlier khleiba from Gothichlaifs, or, rather, from the more ancient form hlaibhaz, which meant bread baked in an oven (and, probably, made with yeast), as different from a l-iepekha, which was a flat cake moulded (liepiti) from paste, and baked on charcoal. [the same nominal stem *hlaibh- has been preserved in modern English as loaf; cf. Lord, from ancient hlafweard bread-keeper]

- ↑ "Russia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ↑ "Vladimir Lenin: From March to October. SparkNotes". Sparknotes.com. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ↑ "Prehistoric man ate flatbread 30,000 years ago: study". Physorg.com. Agence France-Presse. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ↑ McGee, Harold (2004). On food and cooking. Scribner. p. 517. ISBN 0-684-80001-2.

- ↑ Tannahill, Reay (1973). Food in History. Stein and Day. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-8128-1437-1.

- ↑ Chorleywood Industrial Bread Making Process. allotment.org.uk

- ↑ CBS Interactive Inc. White Bread in Wheat Bread's Clothing CBS Early Show. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- ↑ Products / Hovis ~ Brands. rankhovis.co.uk

- ↑ Benhaim, Paul (2003). Modern introduction to hemp: food and fibre: past, present and future. [Mullumbimby, N.S.W.]: P. Benhaim. p. 32. ISBN 0-9751482-0-6.

- ↑ Cicero, Dennis; Czartoryski, Kris; Gruber, Suzanne and Michael, Lipp (2001). The Galaxy Global Eatery Hemp Cookbook. Frog Books. ISBN 1-58394-055-3.

- ↑ Bavec, Martina and Bavec, Franc (2006). Organic Production and Use of Alternative Crops. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd. pp. 177–178. ISBN 1-4200-1742-X.

- ↑ Lamacchia C, Camarca A, Picascia S, Di Luccia A, Gianfrani C (2014). "Cereal-based gluten-free food: how to reconcile nutritional and technological properties of wheat proteins with safety for celiac disease patients". Nutrients (Review) 6 (2): 575–90. doi:10.3390/nu6020575. PMC 3942718. PMID 24481131.

- ↑ Volta U, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Henriksen C, Skodje G, Lundin KE (Jun 2015). "Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a work-in-progress entity in the spectrum of wheat-related disorders". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 29 (3): 477–91. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.04.006. PMID 26060112.

After the confirmation of NCGS diagnosis, according to the previously mentioned work-up, patients are advized to start with a GFD [49]. (...) NCGS patients can experience more symptoms than CD patients following a short gluten challenge [77]. (NCGS=non-celiac gluten sensitivity; CD=coeliac disease; GFD=gluten-free diet)

- ↑ Mulder CJ, van Wanrooij RL, Bakker SF, Wierdsma N, Bouma G (2013). "Gluten-free diet in gluten-related disorders". Dig Dis. (Review) 31 (1): 57–62. doi:10.1159/000347180. PMID 23797124.

The only treatment for CD, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) and gluten ataxia is lifelong adherence to a GFD.

- ↑ Hischenhuber C, Crevel R, Jarry B, Mäki M, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Romano A, Troncone R, Ward R (Mar 1, 2006). "Review article: safe amounts of gluten for patients with wheat allergy or coeliac disease". Aliment Pharmacol Ther 23 (5): 559–75. PMID 16480395.

For both wheat allergy and coeliac disease the dietary avoidance of wheat and other gluten-containing cereals is the only effective treatment.

- ↑ Finley, John H.; Phillips, R. O. (1989). Protein quality and the effects of processing. New York: M. Dekker. p. See Figure 2. ISBN 0-8247-7984-3.

- ↑ Jeffrey Hamelman (2004). Bread: a baker's book of techniques and recipes. New York: John Wiley. pp. 7–13. ISBN 0-471-16857-2.

A high gluten white flour will require more mix time than a white flour with a lower gluten content,...

- ↑ Hydration ratio for breads. Food.laurieashton.com (5 June 2009). Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ Edwards, W.P. (2007). The science of bakery products. Cambridge, Eng: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 68. ISBN 0-85404-486-8. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

When bread expands in the oven the resulting expansion is known as oven spring. It has been calculated that water expansion was responsible for some 60% of the expansion.

- ↑ "Susan R. Brown’s Salt Rising Bread Project". Home.comcast.net. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ↑ Kilcast, D.; McKenna, B. M., ed. (2003). Texture in food. Cambridge, England: Woodhead Pub. p. 448. ISBN 1-85573-724-8.

The arrival of the Pressure-Vacuum mixer, developed by the Flour Milling and Baking Research ASsociation (FMBRA) at Chorleywood, provides bakers with unique opportunities for creating new cell structures in bread products because of the greatly improved possibilities for manipulating gas bubble populations in the mixed dough. Nor are the opportunities limited to the incorporation of air during dough mixing. As long ago as the 1970s FMBRA showed that the modification of the gas composition of the mixer headspace also contributed to bread crumb structure (Chaberlain and Collins, 1979).

- ↑ Young, Linda; Cauvain, Stanley P. (2007). Technology of Breadmaking. Berlin: Springer. p. 54. ISBN 0-387-38563-0.

- ↑ Silverton, Nancy (1996) Breads From The La Brea Bakery, Villard, ISBN 0679409076

- ↑ Reinhart, Peter (2001) The Bread Baker's Apprentice: Mastering the Art of Extraordinary Bread, Ten Speed Press, ISBN 1580082688

- ↑ Gelinas, Pierre; McKinnon, Carole M. (2006). "Effect of wheat variety, farming site, and bread-baking on total phenolics". International Journal of Food Science and Technology 41 (3): 329. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.01057.x.

- ↑ Boskov Hansen, H, Andreasen, MF, Nielsen, MM, Melchior Larsen, L, Bach Knudsen, KE, Meyer, AS, Christensen, LP & Hansen, Å; Andreasen; Nielsen; Larsen; Knudsen; Meyer; Christensen; Hansen (2002). "Changes in dietary fibre, phenolic acids and activity of endogenous enzymes during rye bread-making". European Food Research and Technology 214: 33. doi:10.1007/s00217-001-0417-6.

- ↑ Strandås, C.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Andersson, R.; Åman, P. (2008). "Phenolic glucosides in bread containing flaxseed". Food Chemistry 110 (4): 997. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.088.

- ↑ Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- ↑ Ring, Evelyn (5 October 2009). "Bread that stays fresh for 2 weeks to hit shelves by year-end". Irish Examiner.

- ↑ Vaux, Bert. "Dialect Survey: What do you call the end of a loaf of bread?". Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Winkler, Sarah (29 July 2009). "Discovery Health "Is eating bread crust really good for you?"". Health.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Hofmann, T; Lindenmeier, M; Somoza, V (2005). "Pronyl-Lysine—A Novel Protein Modification in Bread Crust Melanoidins Showing in Vitro Antioxidative and Phase I/II Enzyme Modulating Activity". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1043: 887. Bibcode:2005NYASA1043..887H. doi:10.1196/annals.1333.101.

- ↑ Panneerselvam, J; Aranganathan, S; Nalini, N (2009). "Inhibitory effect of bread crust antioxidant pronyl-lysine on two different categories of colonic premalignant lesions induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine". European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP) 18 (4): 291–302. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832945a6. PMID 19417676.

- ↑ Panneerselvam, Jayabal; Aranganathan, Selvaraj; Nalini, Namasivayam (2009). "Inhibitory effect of bread crust antioxidant pronyl-lysine on two different categories of colonic premalignant lesions induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine". European Journal of Cancer Prevention 18 (4): 291–302. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832945a6. PMID 19417676.

- ↑ "companion". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- 1 2 3 Copeland, Libby (6 April 2012) "White Bread Kills: A history of a national paranoia." Slate

- ↑ Beeton, Mrs (1861). Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management (Facsimile edition, 1968 ed.). London: S.O. Beeton, 18 Bouverie St. E.C. p. 832. ISBN 0-224-61473-8.

- ↑ Flour related traditions and quotes. fabflour.co.uk

- ↑ "Pinoy Tasty arrives". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. 6 October 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Pinoy Tasty, generic bread, debuts at P36 per loaf". GMA News and Public Affairs. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Bread, which is loved, by our neighbors". grazione.ru. 6 July 2012.

- ↑ "El Tamiz: Bread, cheesecake and a bit of variety". foodychile.com. 14 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "Bread Makes the World Go Round". sixservings.org. 15 October 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013.

- ↑ "Chilean Bread". fundi2.com. 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Kamala. "Bread and Salt Ceremony in Europe".

- ↑ Mon dieu! New campaign urges French to eat more bread – TODAY.com

- ↑ Chorleywood, the Bread that Changed Britain. BBC.co.uk (7 June 2011). Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ La histopa del pan. Juntadeandalucia.es. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ Ethiopian Injera Recipe | Exploratorium. Exploratorium.edu. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ "Egyptian Pita / Aish Baladi". breakurfast. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ "Egyptian Bread - 'Eesh baladi' - Egyptian Local Bread". www.ahmedhamdyeissa.com. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Katz, Solomon. Charles Scribner's Sons, (Vol 3 ed.). New York: Gale. p. 531.

- ↑ Thought For Food: An Overview of the Seder. Farbrengen Magazine

- ↑ Eucharist (Christianity) – Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Walter Hazen (1 September 2002). Inside Christianity. Lorenz Educational Press. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

The Anglican Church in England uses the term Holy Communion. In the Roman Catholic Church, both terms are used. Most Protestant churches refer to the sacrament simply as communion or The Lord's Supper. Communion reenacts the Last Supper that Jesus ate with His disciples before He was arrested and crucified.

- ↑ Albury, W. R.; Weisz, G. M. (2009). "Depicting the Bread of the Last Supper" (PDF). Journal of Religion and Society 11: 1–17.

- ↑ Sabrina, Lady (2006). Exploring Wicca: The Beliefs, Rites, and Rituals of the Wiccan Religion. Career Press. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-1-56414-884-1.

- ↑ Sosland, Josh. Bread market remains challenging. Food Business News, 17 September 2013

- ↑ Why Bread Is No Longer Rising. The Huffington Post. 31 October 2012

- ↑ Pećanac, M.; Janjić, Z.; Komarcević, A.; Pajić, M.; Dobanovacki, D.; Misković, SS. (2013). "Burns treatment in ancient times.". Med Pregl 66 (5–6): 263–7. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00603-5. PMID 23888738.

Further reading

- Kaplan, Steven Laurence: Good Bread is Back: A Contemporary History of French Bread, the Way It Is Made, and the People Who Make It. Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8223-3833-8

- Jacob, Heinrich Eduard: Six Thousand Years of Bread. Its Holy and Unholy History. Garden City / New York: Doubleday, Doran and Comp., 1944. New 1997: New York: Lyons & Burford, Publishers (Foreword by Lynn Alley), ISBN 1-55821-575-1 <

- Spiekermann, Uwe: Brown Bread for Victory: German and British Wholemeal Politics in the Inter-War Period, in: Trentmann, Frank and Just, Flemming (ed.): Food and Conflict in Europe in the Age of the Two World Wars. Basingstoke / New York: Palgrave, 2006, pp. 143–171, ISBN 1-4039-8684-3

- Cunningham, Marion (1990). The Fannie Farmer cookbook. illustrated by Lauren Jarrett (13th ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-56788-9.

- Trager, James (1995). The food chronology: a food lover's compendium of events and anecdotes from prehistory to the present. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-3389-0.

- Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- D. Samuel (2000). "Brewing and baking". Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Eds: P.T. Nicholson & I. Shaw. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 537–576. ISBN 0-521-45257-0.

- Pyler, E. J. (1988). Baking Science & Technology 3rd Ed. vols. I & II. Sosland Publishing Company. ISBN 1-882005-02-3.

External links

-

Bread Recipes at Wikibook Cookbooks

Bread Recipes at Wikibook Cookbooks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|