Brazos River

| Brazos River | |

| Texas | |

Brazos River downstream of Possum Kingdom Lake (Palo Pinto County, Texas) | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | Texas |

| Source | Llano Estacado |

| Source confluence | Stonewall County, Texas |

| - elevation | 453 m (1,486 ft) |

| - coordinates | 33°16′07″N 100°0′37″W / 33.26861°N 100.01028°W [1] |

| Mouth | Gulf of Mexico |

| - location | Brazoria County, Texas |

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| - coordinates | 28°52′33″N 95°22′42″W / 28.87583°N 95.37833°WCoordinates: 28°52′33″N 95°22′42″W / 28.87583°N 95.37833°W [1] |

| Length | 1,352 km (840 mi) |

| Basin | 116,000 km2 (44,788 sq mi) |

| Discharge | for Rosharon, TX |

| - average | 237.5 m3/s (8,387 cu ft/s) |

| - max | 2,390 m3/s (84,402 cu ft/s) |

| - min | 0.76 m3/s (27 cu ft/s) |

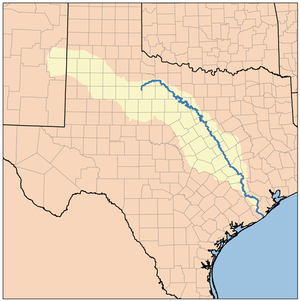

Brazos River Watershed

| |

| Website: Handbook of Texas: Brazos River | |

The Brazos River (![]() i/ˈbræzəs/ BRAZ-əs), called the Rio de los Brazos de Dios (translated as "The River of the Arms of God") by early Spanish explorers and the 11th longest river in the United States at 2,060 km (1,280 mi) from its headwater source at the head of Blackwater Draw, Curry County, New Mexico[2] to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico with a 116,000 km2 (45,000 sq mi) drainage basin.[3]

i/ˈbræzəs/ BRAZ-əs), called the Rio de los Brazos de Dios (translated as "The River of the Arms of God") by early Spanish explorers and the 11th longest river in the United States at 2,060 km (1,280 mi) from its headwater source at the head of Blackwater Draw, Curry County, New Mexico[2] to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico with a 116,000 km2 (45,000 sq mi) drainage basin.[3]

Geography

The Brazos proper begins at the confluence of the Salt Fork and Double Mountain Fork, two tributaries of the Upper Brazos that rise on the high plains of the Llano Estacado, flowing 840 mi (1,350 km) through the center of Texas. Another major tributary of the Upper Brazos is the Clear Fork Brazos River, which passes by Abilene and joins the main river near Graham. Important tributaries of the Lower Brazos include the Bosque River, the Little River, Yegua Creek, Nolan River, the Leon River, the San Gabriel River, the Lampasas River and the Navasota River.[4]

Initially running east towards Dallas-Fort Worth, the Brazos turns south, passing through Waco and the Baylor University campus, further south to near Calvert, Texas then past Bryan and College Station, then through Richmond, Texas in Fort Bend County, and into the Gulf of Mexico in the marshes just south of Freeport.[3]

The main stem of the Brazos is dammed in three places, all north of Waco, forming Possum Kingdom Lake, Lake Granbury, and Lake Whitney. Of these three, Granbury was the last to be completed, in 1969. When its construction was proposed in the mid-1950s, John Graves wrote the book, Goodbye to a River. A small municipal dam (Lake Brazos Dam) is near the downstream city limit of Waco at the end of the Baylor campus; it raises the level of the river through the city to form a town lake. This impoundment of the Brazos through Waco is locally called Lake Brazos. A total of nineteen major reservoirs are located along the Brazos.[5]

-

North Fork Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the eastern edge of the Llano Estacado.

-

An often dry Salt Fork Brazos River 10 mi (16 km) northeast of Post, Texas.

-

Double Mountain Fork Brazos River viewed from the Texas State Highway 70 bridge, 6 mi (9.7 km) north of Rotan, Texas.

-

Collapsed bridge structure, Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the site of former Rath City, Texas.

-

The Brazos in north Central Texas midway between Possum Kingdom and Lake Granbury.

-

The Brazos in southeast Central Texas west of Bryan, Texas.

History

It is unclear when it was first named by European explorers, since it was often confused with the Colorado River not far to the south, but it was certainly seen by La Salle. Later Spanish accounts call it Los Brazos de Dios (the arms of God), for which name there were several different explanations, all involving it being the first water to be found by desperately thirsty parties. In 1842, native Indian commissioner of Texas, Ethan Stroud established a trading post on this river.

Brazos River was the scene of a battle between the Texas Navy and Mexican Navy during the Texas Revolution. Texas Navy ship Independence was defeated by one Mexican vessel.

The river was important for navigation before and after the American Civil War, and steam boats sailed as far up the river as Washington-on-the-Brazos. While attempts to improve commercial navigation on the river continued, railroads proved more reliable. The Brazos River also flooded, often seriously, on a regular basis before a piecemeal levee system was replaced, particularly notably in 1913 when a massive flood affected the course of the river. The river is primarily important today as a source of water for power, irrigation, and recreation. The water is administered by the Brazos River Authority.[6]

The river also features prominently in a number of prison songs, because at one time nearly every prison in Texas was near the Brazos.

The 2000 book, Sandbars and Sternwheelers: Steam Navigation on the Brazos by Pamela A. Puryear and Nath Winfield, Jr., with introduction by J. Milton Nance, examines the early vessels that attempted to sail on the Brazos.[7]

Cultural references

- In the Alan Le May novel The Searchers, and the 1956 film based on it, the Brazos is a. Mose Harper identifies the location of the camp of Chief Scar who is holding the captive child Debbie, as Seven Fingers, which a group of Texas Rangers identify as Seven Fingers of the Brazos.

- John Graves' travel narrative Goodbye to a River takes place on the Brazos River.

- The Brazos is mentioned in the Old Crow Medicine Show song "Take 'em away".

- The Brazos is the setting of the American folk song "Ain't No More Cane".

- The John Hiatt song "The River Knows Your Name" from the album Walk On references the Brazos.

- K.R. Wood's "Fathers of Texas" song "Brazos River Song", performed by Townes Van Zandt as the "Texas River Song."

- The Brazos is mentioned in three Lyle Lovett songs: "Walk Through the Bottomland"; "Texas River Song" on the album Step Inside This House; and "Front Porch Song", which Lovett co-wrote with Robert Earl Keen, on Lovett's eponymous first recording.

- The Brazos is mentioned in the Dub Miller song, "Livin on Lonestar Time".

- The Brazos is mentioned in the Dan Bern song, "We Will Not Be Divided".

- The Dutch band "The Walkers" had a hit in the 1970s with the song "There's No More Corn On The Brasos".

- The Brazos is forded by "The Kid" character in Cormac McCarthy's novel Blood Meridian.

- The lukewarm headwaters of the Mighty Brazos River is the source of Alamo Beer in Fox Network's King of the Hill.

- Billy Walker mentioned the Brazos in "Cross the Brazos at Waco".

- The former boomtown and subsequent virtual ghost town of Desdemona in Eastland County, founded in 1857, was the first Texas community located west of the Brazos River.

- The Brazos is the focal point of a song performed by Gov't Mule and Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top called "Broke Down on the Brazos".

- The Brazos is mentioned is F. L. Light's drama, "A Systemic Consummation".[8]

- A version of "Ain't No More Cane on the Brazos" sung by Rick Danko, Janis Joplin, and others, can be seen on the music documentary Festival Express.

- In 1980, Lester Bangs recorded the album Jook Savages on the Brazos with the Austin punk group The Delinquents.

- James A. Michener's historical novel Texas. has numerous references to the Brazos River, especially its flooding.

- The band Gov't Mule had the sone "Broke Down On the Brazos" on the album "By a Thread".

- In the film The Over-the-Hill Gang Rides Again, elderly former Texas Rangers use "Brazos" as a rallying call, with the meaning "A ranger needs help".

- The song "Brazos" by Matthew E. White from 2012 is named after the river.

- The song "Keep The Wolves Away" by Uncle Lucius mentions the Brazos.

- The rivalry game between Texas A&M and Baylor is referred to as the Battle of the Brazos.

- The Whitey Shafer song All my exes live in Texas mentions this river

See also

References

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Brazos River

- ↑ Kammerer, J.C. (1987). "Largest Rivers in the United States". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- 1 2 Hendrickson, Kenneth E., Jr. (1999-02-15). "Brazos River". The Handbook of Texas Online. The General Libraries at the University of Texas at Austin and the Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ Hendrickson, Jr., Kenneth E. (1981). The Waters of the Brazos: A History of the Brazos River Authority 1929-1979. Waco, TX: The Texian Press.

- ↑ "River Basin Map of Texas" (JPEG). Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin. 1996. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- ↑ Hendrickson, Jr., Kenneth E. (1981). The Waters of the Brazos: A History of the Brazos River Authority 1929-1979. Waco, TX: The Texian Press.

- ↑ Sandbars and Sternwheelers: Steam Navigation on the Brazos. Texas A&M University Press, 2000, 168 pp., ISBN 1-58544-058-2. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ↑

Further reading

- Archer, Kenna Lang. Unruly Waters: A Social and Environmental History of the Brazos River. (University of New Mexico Press, 2015). xxviii, 260 pp.

- Hendrickson, Jr., Kenneth E. The Waters of the Brazos: A History of the Brazos River Authority 1929-1979 (Waco, TX: The Texian Press, 1981).

- Kimmel, Jim. 2011. "Exploring the Brazos River: from beginning to end". Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brazos River. |

- Brazos River from the Handbook of Texas Online

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Brazos River

- Photos of the Upper Brazos

- Historic photos of Army Corps of Engineers lock and dam projects on the Brazos River, 1910-20s, from the Portal to Texas History

- See an 1858 map Preliminary chart of entrance to Brazos River, Texas / from a trigonometrical survey under the direction of A. Bache ; triangulation by J.S. Williams ; topography by J.M. Wampler ; hydrography by the parties under the command of E.J. De Haven & J.K. Duer., hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Brazos River Authority