Branch retinal vein occlusion

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) is a common retinal vascular disease of the elderly. It is caused by the occlusion of one of the branches of central retinal vein.[1]

Epidemiology

- BRVO is 3 times more common than CRVO.

- Usual age of onset is 60–70 years.

- An analysis of population from several countries estimates that approximately 16 million people worldwide may have retinal vein occlusion.[2]

Risk factors

Studies have identified the following abnormalities as risk factors for the development of BRVO:

Diabetes mellitus was not a major independent risk factor.

Manifestations

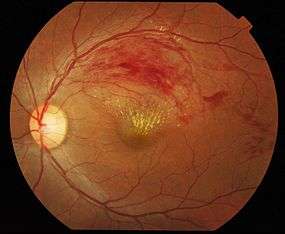

Patients with BRVO usually complain of sudden onset of blurred vision or a central visual field defect. The eye examination findings of acute BRVO include superficial hemorrhages, retinal edema, and often cotton-wool spots in a sector of retina drained by the affected vein.The obstructed vein is dilated and tortuous.

The quadrant most commonly affected is the superotemporal (63%).

Retinal neovascularization occurs in 20% of cases within the first 6–12 months of occlusion and depends on the area of retinal nonperfusion. Neovascularization is more likely to occur if more than five disc diameters of nonperfusion are present and vitreous hemorrhage can ensue.[3]

Diagnosis and testing

The diagnosis of BRVO is made clinically by finding retinal hemorrhages in the distribution of an obstructed retinal vein.

- Fluorescein angiography is a helpful adjunct. Findings include delayed venous filling, hypofluorescence caused by hemorrhage and capillary nonperfusion, dilation and tortuosity of veins, leakage due to neovascularization and macular edema.

- Optical coherence tomography is an adjunctive test in BRVO. Macular edema is commonly seen in BRVO in OCT exams. Serial OCT is used as a rapid and noninvasive way of monitoring the macular edema.

Treatment

Several options exist for the treatment of BRVO. These treatments aim for the two of the most significant complications of BRVO, namely macular edema and neovascularization.[1]

- Systemic treatment with oral Aspirin, subcutaneous Heparin, or intravenous thrombolysis have not been shown to be effective treatments for CRVO and for BRVO no reliable clinical trial has been published.

- Laser treatment of the macular area to reduce macular edema is indicated in patients who have 20/40 or worse vision and did not spontaneously improve for at least 3 months (to permit the maximum spontaneous resolution) after the development of the vein occlusion. It is typically administered with the argon laser and is focused on edematous retina within the arcades drained by the obstructed vein and avoiding the foveal avascular zone. Leaking microvascular abnormalities may be treated directly, but prominent collateral vessels should be avoided.

- The second indication of laser treatment is in case of neovascularization. Retinal photocoagulation is applied to the involved retina to cover the entire involved segment, extending from the arcade out to the periphery. Ischemia alone is not an indication for treatment provided that follow-up could be maintained.

- Preservative-free, nondispersive Triamcinolone acetonide in 1 or 4 mg dosage may be injected into the vitreous to treat macular edema but has complications including elevated intraocular pressure and development of cataract. Triamcinolone injection is shown to have similar effect on visual acuity when compared with standard care (Laser therapy), However, the rates of elevated intraocular pressure and cataract formation is much higher with the triamcinolone injection, especially the higher dosage.[4] Intravitreal injection of Dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex; 700,350 μg) is being studied, its effect may last for 180 days. The injection may be repeated however with less pronounced effect. Although the implant was designed to cause less complications, pressure rise and cataract formation is noted with this treatment too.[5]

- Anti-VEGF drugs such as Bevacizumab (Avastin; 1.25 -2.5 mg in 0.05ml) and Ranibizumab (lucentis) injections are being used and investigated. Intravitreal anti-VEGFs have a low incidence of adverse side effects compared with intravitreal corticosteroids, but are currently short acting requiring frequent injections. Anti-VEGF injection may be used for macular edema or neovascularization. The mechanism of action and duration of anti-VEGF effect on macular edema is currently unknown. The intraocular levels of VEGF are increased in eyes with macular edema secondary to BRVO and the elevated VEGF levels are correlated to the degree and severity of the areas of capillary nonperfusion and macular edema.[6]

- Surgery is employed occasionally for longstanding vitreous hemorrhage and other serious complications such as epiretinal membrane and retinal detachment.

- Arteriovenous sheathotomy has been reported in small, uncontrolled series of patients with BRVO. BRVO typically occurs at arteriovenous crossings, where the artery and vein share a common adventitial sheath. In arteriovenous sheathotomy an incision is made in the adventitial sheath adjacent to the arteriovenous crossing and is extended along the membrane that holds the blood vessels in position to the point where they cross, the overlying artery is then separated from the vein.

Course and outcome

In general, BRVO has a good prognosis: after 1 year 50–60% of eyes have been reported to have a final VA of 20/40 or better even without any treatment. With time the dramatic picture of an acute BRVO becomes more subtle, hemorrhages fade so that the retina can look almost normal. Collateral vessels develop to help drain the affected area.

See also

References

- 1 2 Basic and clinical science course (2011–2012). Retina and vitreous. American Academy of Ophthalmology. pp. 150–154. ISBN 978-1615251193.

- ↑ Rogers, S; et al. (Feb 2010). "The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia.". Ophthalmology 117 (2): 313–9.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.017. PMC 2945292. PMID 20022117.

- ↑ Myron Yanoff, Jay S. Duker (2009). Ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 9780323043328.

- ↑ Scott, IU; et al. (Sep 2009). "A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with standard care to treat vision loss associated with macular Edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion: the Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) study report 6.". Archives of ophthalmology 127 (9): 1115–28. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.233. PMC 2806600. PMID 19752420.

- ↑ Haller, JA; et al. (Dec 2011). "Dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema related to branch or central retinal vein occlusion twelve-month study results.". Ophthalmology 118 (12): 2453–60. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.014. PMID 21764136.

- ↑ Karia, N (Jul 30, 2010). "Retinal vein occlusion: pathophysiology and treatment options.". Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.) 4: 809–16. doi:10.2147/opth.s7631. PMC 2915868. PMID 20689798.