Branch point

In the mathematical field of complex analysis, a branch point of a multi-valued function (usually referred to as a "multifunction" in the context of complex analysis) is a point such that the function is discontinuous when going around an arbitrarily small circuit around this point.[1] Multi-valued functions are rigorously studied using Riemann surfaces, and the formal definition of branch points employs this concept.

Branch points fall into three broad categories: algebraic branch points, transcendental branch points, and logarithmic branch points. Algebraic branch points most commonly arise from functions in which there is an ambiguity in the extraction of a root, such as solving the equation z = w2 for w as a function of z. Here the branch point is the origin, because the analytic continuation of any solution around a closed loop containing the origin will result in a different function: there is non-trivial monodromy. Despite the algebraic branch point, the function w is well-defined as a multiple-valued function and, in an appropriate sense, is continuous at the origin. This is in contrast to transcendental and logarithmic branch points, that is, points at which a multiple-valued function has nontrivial monodromy and an essential singularity. In geometric function theory, unqualified use of the term branch point typically means the former more restrictive kind: the algebraic branch points.[2] In other areas of complex analysis, the unqualified term may also refer to the more general branch points of transcendental type.

Algebraic branch points

Let Ω be a connected open set in the complex plane C and ƒ:Ω → C a holomorphic function. If ƒ is not constant, then the set of the critical points of ƒ, that is, the zeros of the derivative ƒ'(z), has no limit point in Ω. So each critical point z0 of ƒ lies at the center of a disc B(z0,r) containing no other critical point of ƒ in its closure.

Let γ be the boundary of B(z0,r), taken with its positive orientation. The winding number of ƒ(γ) with respect to the point ƒ(z0) is a positive integer called the ramification index of z0. If the ramification index is greater than 1, then z0 is called a ramification point of ƒ, and the corresponding critical value ƒ(z0) is called an (algebraic) branch point. Equivalently, z0 is a ramification point if there exists a holomorphic function φ defined in a neighborhood of z0 such that ƒ(z) = φ(z)(z − z0)k for some positive integer k > 1.

Typically, one is not interested in ƒ itself, but in its inverse function. However, the inverse of a holomorphic function in the neighborhood of a ramification point does not properly exist, and so one is forced to define it in a multiple-valued sense as a global analytic function. It is common to abuse language and refers to a branch point w0 = ƒ(z0) of ƒ as a branch point of the global analytic function ƒ−1. More general definitions of branch points are possible for other kinds of multiple-valued global analytic functions, such as those that are defined implicitly. A unifying framework for dealing with such examples is supplied in the language of Riemann surfaces below. In particular, in this more general picture, poles of order greater than 1 can also be considered ramification points.

In terms of the inverse global analytic function ƒ−1, branch points are those points around which there is nontrivial monodromy. For example, the function ƒ(z) = z2 has a ramification point at z0 = 0. The inverse function is the square root ƒ−1(w) = w1/2, which has a branch point at w0 = 0. Indeed, going around the closed loop w = eiθ, one starts at θ = 0 and ei0/2 = 1. But after going around the loop to θ = 2π, one has e2πi/2 = −1. Thus there is monodromy around this loop enclosing the origin.

Transcendental and logarithmic branch points

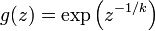

Suppose that g is a global analytic function defined on a punctured disc around z0. Then g has a transcendental branch point if z0 is an essential singularity of g such that analytic continuation of a function element once around some simple closed curve surrounding the point z0 produces a different function element.[3] An example of a transcendental branch point is the origin for the multi-valued function

for some integer k > 1. Here the monodromy group for a circuit around the origin is finite. Analytic continuation around k full circuits brings the function back to the original.

By contrast, the point z0 is called a logarithmic branch point if it is impossible to return to the original function element by analytic continuation along a curve with nonzero winding number about z0. This is so called because the typical example of this phenomenon is the branch point of the complex logarithm at the origin. Going once counterclockwise around a simple closed curve encircling the origin, the complex logarithm is incremented by 2πi. Encircling a loop with winding number w, the logarithm is incremented by 2πi w and the monodromy group is the infinite cyclic group  .

.

There is no corresponding notion of ramification for transcendental and logarithmic branch points since the associated covering Riemann surface cannot be analytically continued to a cover of the branch point itself. Such covers are therefore always unramified.

Examples

- 0 is a branch point of the square root function. Suppose w = z1/2, and z starts at 4 and moves along a circle of radius 4 in the complex plane centered at 0. The dependent variable w changes while depending on z in a continuous manner. When z has made one full circle, going from 4 back to 4 again, w will have made one half-circle, going from the positive square root of 4, i.e., from 2, to the negative square root of 4, i.e., −2.

- 0 is also a branch point of the natural logarithm. Since e0 is the same as e2πi, both 0 and 2πi are among the multiple values of ln(1). As z moves along a circle of radius 1 centered at 0, w = ln(z) goes from 0 to 2πi.

- In trigonometry, since tan(π/4) and tan (5π/4) are both equal to 1, the two numbers π/4 and 5π/4 are among the multiple values of arctan(1). The imaginary units i and −i are branch points of the arctangent function arctan(z) = (1/2i)log[(i − z)/(i + z)]. This may be seen by observing that the derivative (d/dz) arctan(z) = 1/(1 + z2) has simple poles at those two points, since the denominator is zero at those points.

- If the derivative ƒ ' of a function ƒ has a simple pole at a point a, then ƒ has a logarithmic branch point at a. The converse is not true, since the function ƒ(z) = zα for irrational α has a logarithmic branch point, and its derivative is singular without being a pole.

Branch cuts

Roughly speaking, branch points are the points where the various sheets of a multiple valued function come together. The branches of the function are the various sheets of the function. For example, the function w = z1/2 has two branches: one where the square root comes in with a plus sign, and the other with a minus sign. A branch cut is a curve in the complex plane such that it is possible to define a single analytic branch of a multi-valued function on the plane minus that curve. Branch cuts are usually, but not always, taken between pairs of branch points.

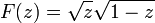

Branch cuts allow one to work with a collection of single-valued functions, "glued" together along the branch cut instead of a multivalued function. For example, to make the function

single-valued, one makes a branch cut along the interval [0, 1] on the real axis, connecting the two branch points of the function. The same idea can be applied to the function √z; but in that case one has to perceive that the point at infinity is the appropriate 'other' branch point to connect to from 0, for example along the whole negative real axis.

The branch cut device may appear arbitrary (and it is); but it is very useful, for example in the theory of special functions. An invariant explanation of the branch phenomenon is developed in Riemann surface theory (of which it is historically the origin), and more generally in the ramification and monodromy theory of algebraic functions and differential equations.

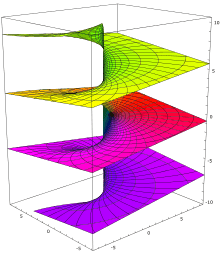

Complex logarithm

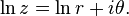

The typical example of a branch cut is the complex logarithm. If a complex number is represented in polar form z = reiθ, then the logarithm of z is

However, there is an obvious ambiguity in defining the angle θ: adding to θ any integer multiple of 2π will yield another possible angle. A branch of the logarithm is a continuous function L(z) giving a logarithm of z for all z in a connected open set in the complex plane. In particular, a branch of the logarithm exists in the complement of any ray from the origin to infinity: a branch cut. A common choice of branch cut is the negative real axis, although the choice is largely a matter of convenience.

The logarithm has a jump discontinuity of 2πi when crossing the branch cut. The logarithm can be made continuous by gluing together countably many copies, called sheets, of the complex plane along the branch cut. On each sheet, the value of the log differs from its principal value by a multiple of 2πi. These surfaces are glued to each other along the branch cut in the unique way to make the logarithm continuous. Each time the variable goes around the origin, the logarithm moves to a different branch.

Continuum of poles

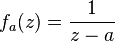

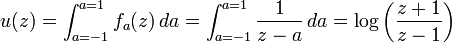

One reason that branch cuts are common features of complex analysis is that a branch cut can be thought of as a sum of infinitely many poles arranged along a line in the complex plane with infinitesimal residues. For example,

is a function with a simple pole at z = a. Integrating over the location of the pole:

defines a function u(z) with a cut from −1 to 1. The branch cut can be moved around, since the integration line can be shifted without altering the value of the integral so long as the line does not pass across the point z.

Riemann surfaces

The concept of a branch point is defined for a holomorphic function ƒ:X → Y from a compact connected Riemann surface X to a compact Riemann surface Y (usually the Riemann sphere). Unless it is constant, the function ƒ will be a covering map onto its image at all but a finite number of points. The points of X where ƒ fails to be a cover are the ramification points of ƒ, and the image of a ramification point under ƒ is called a branch point.

For any point P ∈ X and Q = ƒ(P) ∈ Y, there are holomorphic local coordinates z for X near P and w for Y near Q in terms of which the function ƒ(z) is given by

for some integer k. This integer is called the ramification index of P. Usually the ramification index is one. But if the ramification index is not equal to one, then P is by definition a ramification point, and Q is a branch point.

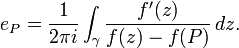

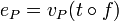

If Y is just the Riemann sphere, and Q is in the finite part of Y, then there is no need to select special coordinates. The ramification index can be calculated explicitly from Cauchy's integral formula. Let γ be a simple rectifiable loop in X around P. The ramification index of ƒ at P is

This integral is the number of times ƒ(γ) winds around the point Q. As above, P is a ramification point and Q is a branch point if eP > 1.

Algebraic geometry

In the context of algebraic geometry, the notion of branch points can be generalized to mappings between arbitrary algebraic curves. Let ƒ:X → Y be a morphism of algebraic curves. By pulling back rational functions on Y to rational functions on X, K(X) is a field extension of K(Y). The degree of ƒ is defined to be the degree of this field extension [K(X):K(Y)], and ƒ is said to be finite if the degree is finite.

Assume that ƒ is finite. For a point P ∈ X, the ramification index eP is defined as follows. Let Q = ƒ(P) and let t be a local uniformizing parameter at P; that is, t is a regular function defined in a neighborhood of Q with t(Q) = 0 whose differential is nonzero. Pulling back t by ƒ defines a regular function on X. Then

where vP is the valuation in the local ring of regular functions at P. That is, eP is the order to which  vanishes at P. If eP > 1, then ƒ is said to be ramified at P. In that case, Q is called a branch point.

vanishes at P. If eP > 1, then ƒ is said to be ramified at P. In that case, Q is called a branch point.

Puiseux series

Notes

References

- Ablowitz, Mark J.; Fokas, Athanassios S. (2003), Complex Variables: Introduction and Applications, Cambridge Texts in Applied Mathematics (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53429-1

- Ahlfors, L. V. (1979), Complex Analysis, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-000657-7

- Arfken, G. B.; Weber, H. J. (2000), Mathematical Methods for Physicists (5th ed.), Boston, MA: Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-059825-0

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, MR 0463157, OCLC 13348052

- Markushevich, A. I. (1965), Theory of functions of a complex variable. Vol. I, Translated and edited by Richard A. Silverman, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall Inc., MR 0171899

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001), "Branch point", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4