Bowhead whale

| Bowhead whale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Cetacea |

| Suborder: | Mysticeti |

| Family: | Balaenidae |

| Genus: | Balaena Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species: | B. mysticetus |

| Binomial name | |

| Balaena mysticetus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

| Bowhead whale range | |

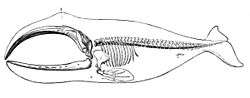

The bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) is a species of the right whale family Balaenidae, in suborder Mysticeti, and genus Balaena. A stocky dark-colored whale without a dorsal fin, it can grow 14 m (46 ft) to 18 m (59 ft) in length. This thick-bodied species can weigh from 75 tonnes (74 long tons; 83 short tons) to 100 tonnes (98 long tons; 110 short tons).[3] They live entirely in fertile Arctic and sub-Arctic waters, unlike other whales that migrate to low latitude waters to feed or reproduce. The bowhead was also known as the Greenland right whale or Arctic whale. American whalemen called them the steeple-top, polar whale,[4] or Russia or Russian whale. The bowhead has the largest mouth of any animal.[5]

The bowhead was an early whaling target. The population was severely reduced before a 1966 moratorium was passed to protect the species. Through conservation efforts, the bowhead population has since recovered and is now rated "Least Concern" on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[2]

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus first described this whale in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae (1758).[6] Seemingly identical to its cousins in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Oceans, they were all thought to be a single species, collectively known as the "right whale", and given the binomial name Balaena mysticetus.

Today, the bowhead whale occupies a monotypic genus, separate from the right whales, as was proposed by the work of John Edward Gray in 1821.[7] For the next 180 years, the family Balaenidae was the subject of great taxonometric debate. Authorities have repeatedly recategorized the three populations of right whale plus the bowhead whale, as one, two, three or four species, either in a single genus or in two separate genera. Eventually, it was recognized that bowheads and right whales were in fact different, but there was still no strong consensus as to whether they shared a single genus or two. As recently as 1998, Dale Rice, in his comprehensive and otherwise authoritative classification, Marine mammals of the world: systematics and distribution, listed just two species: B. glacialis (the right whales) and B. mysticetus (the bowheads).[8]

Studies in the 2000s finally provided clear evidence that the three living right whale species do comprise a phylogenetic lineage, distinct from the bowhead, and that the bowhead and the right whales are rightly classified into two separate genera.[9] The right whales were thus confirmed to be in a separate genus, Eubalaena. The relationship is shown in the cladogram below:

| Family Balaenidae | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| The bowhead whale, genus Balaena, in the family Balaenidae (extant taxa only)[10] |

Balaena prisca, one of the five Balaena fossils from the late Miocene (~10 Mya) to early Pleistocene (~1.5 Mya), may be the same as the modern bowhead whale. The earlier fossil record shows no related cetacean after Morenocetus, found in a South American deposit dating back 23 million years.

An unknown species of right whale, the so-called "Swedenborg whale" which was proposed by Emanuel Swedenborg in the 18th century, was once thought to be a North Atlantic right whale by scientific consensus. However based on later DNA analysis those fossil bones claimed to be from "Swedenborg whales" were confirmed to be from bowhead whales.[11]

Description

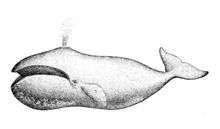

The bowhead whale has a large, robust, dark-colored body and a white chin/lower jaw. They have a massive triangular skull which is used to break through the Arctic ice to breathe. Inuit hunters have reported bowheads surfacing through 60 cm (24 in) of ice.[12] Bowheads also have a strongly bowed lower jaw and narrow upper jaw. Its baleen is the longest of any whale at 3 m (9.8 ft), and is used to strain tiny prey from the water. The bowhead whale has paired blowholes, located at the highest point of the head, that can spout a blow 20 feet high. Its blubber is the thickest of any animal, averaging 43–50 cm (17–20 in). Unlike most cetaceans, bowheads do not have a dorsal fin.[13]

Bowhead whales are comparable in size to the three species of right whales. According to whaling captain William Scoresby, Jr., the longest bowhead he measured was 17.7 m (58 ft) long, while the longest measurement he had ever heard of was of a 20.4 m (67 ft) whale caught at Godhavn, Greenland in the spring of 1813. He also spoke of one caught near Spitsbergen around 1800 that was allegedly nearly 21.3 m (70 ft) in length. However, it is questionable whether these lengths were actually measured.[14] The longest reliably measured length of each sex were of a 16.2 m (53 ft) male and an 18 m (59 ft) female, both harvested and landed in Alaska.[15] Female bowheads are typically larger in size compared to males.

Analysis of hundreds of DNA samples from living whales and from baleen used in vessels, toys, and housing material has shown that Arctic bowhead whales have lost a significant portion of their genetic diversity in the past 500 years. Bowheads originally crossed ice-covered inlets and straits to exchange genes between Atlantic and Pacific populations. This conclusion was derived from analyzing maternal lineage using mitochondrial DNA. However, whaling and climatic cooling between the 16th and 19th centuries — known as the Little Ice Age — is predicted to have reduced the whales’ summer habitats, which explains the loss of genetic diversity.[16]

A recent discovery has elucidated the function of the Bowhead's large palatal retial organ. The bulbous ridge of highly vascularized tissue, termed the corpus cavernosum maxillaris, extends along the center of the hard plate, forming two large lobes at the rostral palate. The tissue is histologically similar to the corpus cavernosum of the mammalian penis. It is hypothesized that this organ provides a mechanism of cooling for the whale (which is normally protected from the cold Arctic waters by 40 cm or more of fat). During times of physical exertion, the whale must cool itself to prevent hyperthermia (and ultimately brain damage). It is now believed this organ engorges with blood, causing the whale to respond by opening its mouth to allow cold seawater to flow over the organ, thus cooling the blood.[17]

Behavior

.jpg)

Swimming

Bowhead whales are not social animals, typically traveling alone or in small pods of up to 6. They are able to dive and remain submerged underwater for up to an hour. However, the time spent underwater in a single dive is usually limited to 4–15 minutes.[12] Bowheads are not thought to be deep divers but they can reach a depth of up to 500 feet. These whales are slow swimmers, normally traveling at about 2–5 km/hr.[18] When fleeing from danger, they can travel at a speed of 10 km/hr. During periods of feeding, the average swim speed is reduced to 1.1 – 2.5 m/s.[19]

Feeding

The head of the bowhead whale comprises a third of its body length, creating an enormous feeding apparatus.[19] Bowhead whales are filter feeders, feeding by swimming forward with its mouth wide open.[12] The whale has hundreds of overlapping baleen plates consisting of keratin hanging from each side of the upper jaw. The mouth has a large upturning lip on the lower jaw that helps to reinforce and hold the baleen plates within the mouth. This also prevents buckling or breakage of the plates from the pressure of the water passing through them as the whale advances. To feed, water is filtered through the fine hairs of keratin of the baleen plates, trapping the prey inside near the tongue where it is then swallowed.[20] The diet consists of mostly zooplankton which includes copepods, amphipods, and many other crustaceans.[19] Approximately 2 tons of food is consumed each day.[20] While foraging, bowheads are solitary.

Vocalization

Bowhead whales are highly vocal and are the most vocal of large whales. They use underwater sounds to communicate while traveling, feeding, and socializing. Intense calls for communication and navigation are produced especially during migration season. During breeding season, bowheads make long, complex, variable songs for mating calls.[18]

Reproduction

Sexual activity occurs between pairs and in boisterous groups of several males and one or two females. Breeding season is observed from March through August; conception is believed to occur primarily in March when song activity is at its highest.[18] Reproduction can begin when a whale is 10 to 15 years old. The gestation period is 13–14 months with females producing a calf once every three to four years.[12] Lactation typically lasts about a year. To survive in the cold water immediately after birth, calves are born with a thick layer of blubber. Within 30 minutes of birth, bowhead calves are able to swim on their own. A newborn calf is about 4.5 m (15 ft) long, weighs approximately 1,000 kg (2,200 lb), and grows to 9 m (30 ft) within the first year.[13]

Health

Lifespan

Bowhead whales are known to be the longest-living mammals, living for over 200 years.[21] In May 2007, a 15 m (49 ft) specimen caught off the Alaskan coast was discovered with the head of an explosive harpoon embedded deep under its neck blubber. The 3.5-inch (89 mm) arrow-shaped projectile was manufactured in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a major whaling center, around 1890, suggesting the animal may have survived a similar hunt more than a century ago.[22][23][24] This whale was estimated to be 211 years old.[25] Other bowhead whales found on the whaling expedition were estimated to be between 135 and 172 years old. This discovery showed the longevity of the bowhead whale is much greater than originally thought.

Genetic Causes

It was previously believed the more cells present in an organism, the greater the chances of mutations that cause age related diseases and cancer.[26] Although the bowhead whale has thousands of times more cells than other mammals, the whale has a much higher resistance to cancer and aging. In 2015, scientists from the US and UK were able to successfully map the whale's genome.[27] Through comparative analysis, two alleles that could be responsible for the whale's longevity were identified. These two specific gene mutations linked to the bowhead whale's ability to live longer are the ERCC1 gene and the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) gene. ERCC1 is linked to DNA repair as well as increased cancer resistance. PCNA is also important in DNA repair. These mutations enable bowhead whales to better repair DNA damage, allowing for greater resistance to cancer.[26] The whale's genome may also reveal physiological adaptations such as having low metabolic rates compared to other mammals.[28] Changes in the gene UCP1, a gene involved in thermoregulation, can explain differences in the metabolic rates in cells.

Ecology

Range and habitat

The bowhead whale is the only baleen whale to spend its entire life in the Arctic and sub-Arctic waters.[12] The Alaskan population spends the winter months in the southwestern Bering Sea. The group migrates northward in the spring, following openings in the ice, into the Chukchi and Beaufort seas.[29] It has been confirmed the whale's range varies depending on climate changes and on the forming/melting of ice.[30]

Population

The bowhead population around Alaska has increased since commercial whaling ceased. Alaska Natives continue to kill small numbers in subsistence hunts each year. This level of killing (25–40 animals annually) is not expected to affect the population's recovery. The population off Alaska's coast (the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock) appears to be recovering and was at about 10,500 animals as of 2001. The status of other populations is less well known. There were about 1,200 off West Greenland in 2006, while the Svalbard population may only number in the tens. However, the numbers have been increasing in recent years.[31]

In March 2008, Canada's Department of Fisheries and Oceans stated the previous estimates in the eastern Arctic had under-counted, with a new estimate of 14,400 animals (range 4,800–43,000).[32] These larger numbers correspond to prewhaling estimates, indicating the population has fully recovered. However, if climate change substantially shrinks sea ice, these whales could be threatened by increased shipping traffic.[33]

Hudson Bay to Foxe Basin

_(20330377360).jpg)

Hudson Bay – Foxe Basin population is distinct from the Baffin Bay – Davis Strait group.[34] Original population size of this local group is unclear, but possibly around 500 to 600 whales annually summered in the northwestern part of the bay in 1860s.[35] Likely, the number of whales actually inhabit within Hudson Bay is much smaller than the total population size of this group,[36] and despite current population size is rather unclear, reports from local indigenous people indicate this population is at least increasing over decades.[37] Larger portions of usages of the bay is considered to be summering while wintering is on smaller scale where some animals winter in Hudson Strait most notably north of Igloolik Island and northeastern Hudson Bay. Distribution patterns of whales in this regions are largely affected by presences of killer whales and bowheads can disappear from normal ranges due to recent changes in killer whales' occurrences within the bay possibly because of changes in movements of ice floes by changing climate.[37] Whaling grounds in 19th century covered from Marble Island to Roes Welcome Sound and to Lyon Inlet and Fisher Strait, and whales still migrate through most of these areas.

Mostly, distributions within Hudson Bay is restricted in northwestern part[34] along with Repulse Bay, Frozen Strait, northern Foxe Basin, and north of Igloolik in summer,[37] and satellite tracking[38] indicates that some portions of the group within the bay do not venture further south than areas south of Coasts and Mansel Islands.[39][40] Cow - calf pairs and juveniles up to 13.5 metres in length consist of majority of summering aggregation in northern Foxe Basin while matured males and non-calving females may utilize northwestern part of Hudson Bay.[37] Fewer whales also migrate to west coast of Hudson Bay, Mansel and Ottawa Islands.[37] Bowhead ranges within Hudson Bay are usually considered not to cover southern parts,[36][41] but at least some whales migrate into further south such as at Sanikiluaq[42] and Churchill river mouth.[43][44]

Congregation within Foxe Basin occurs in a well-defined area at 3,700 km north of Igloolik Island to Fury and Hecla Strait and Jens Munk Island and Gifford Fiord, and into Gulf of Boothia and Prince Regent Inlet. Northward migrating along western Foxe Basin to eastern side of the basin also occurs in spring seasons.[37]

Sea of Okhotsk

Not much is known about the endangered Sea of Okhotsk population. To learn more about the population, these mammals have been regularly observed near the Shantar Islands, very close to the shore, such as at Ongachan Bay.[46][47] Several companies provide whale watching services which are mostly land-based. According to Russian scientists, this total population likely does not exceed 400 animals.[45] Scientific research on this population was seldom done before 2009, when researchers studying Belugas noticed concentrations of Bowheads in the study area. Thus, bowheads in the Sea of Okhotsk were once called "forgotten whales" by researchers. With support from WWF, Russian scientists and nature conservationists cooperated to create a cetacean sanctuary in the Magadan region. This region covers vast areas of the northwestern Sea of Okhotsk, including the Shantar regions.[48] Cetacean species benefiting from this proposal include several critically endangered species such as North Pacific right whales, western Gray whales, and the smaller Belugas, or white whales (Delphinapterus leucas). International support from several other organizations has been offered.[45]

Possibly, vagrants from this population occasionally reach into Asian nations such as off Japan or Korean Peninsula (although this record might or might not be of a right whale[49]). First documented report of the species in Japanese waters was of a strayed infant (7 meters) caught in Osaka Bay on June 23, 1969,[50] and the first living sighting was of a 10 meters juvenile around Shiretoko Peninsula (the southernmost of ice floe range in the world) on June 21 to 23, June in 2015.[51] Fossils have been excavated on Hokkaido,[52] but it is unclear whether or not northern coasts of Japan once had been included in seasonal or occasional migration ranges.

Russian Arctic

The most endangered and historically the largest of all Bowhead populations is the Svalbard/Spitsbergen population.[53] Occurring normally in Fram Strait,[54] Barents Sea and Severnaya Zemlya along Kara Sea[31] to Laptev Sea and East Siberian Sea regions, these whales were seen in entire coastal regions in European and Russian Arctic, even reaching to Icelandic and Scandinavian coasts and Jan Mayen in Greenland Sea, and west of Cape Farewell and western Greenland coasts.[55] Also, Bowheads in this stock were possibly once abundant in areas adjacent to the White Sea region, where few or no animals currently migrate, such as the Kola and Kanin Peninsula. Today, the number of sightings in elsewhere are very small,[56] but with increasing regularities[57] with whales having strong regional connections.[58] Whales have also started approaching townships and inhabited areas such as around Longyearbyen.[59] The waters around the marine mammal sanctuary[60] of Franz Josef Land is possibly functioning as the most important habitat for this population.[61][62]

Current status of population structure of this stock is unclear; whether they are remnant of the historic Svalbard group, re-colonized individuals from other stocks, or if a mixing of these two or more stocks had taken place. In 2015, discoveries of the refuge along eastern Greenland where whaling ships could not reach due to ice floes[63] and largest numbers of whales (80–100 individuals) ever sighted between Spitsbergen and Greenland[64] indicate that more whales than previously considered survived whaling periods, and flows from the other populations are possible.

Possible moulting area on Baffin Island

During expeditions by a tour operator 'Arctic Kingdom', a large group of Bowheads seemingly involved in courtship activities were discovered in very shallow bays in south of Qikiqtarjuaq in 2012.[65] Floating skins and rubbing behaviors at sea bottom indicated possible moulting had taken place. Moulting behaviors had never or had seldomly been documented for this species before. This area is an important habitat for whales that were observed to be relatively active and to interact with humans positively, or to rest on sea floors. These whales belong to Davis Strait stock.

Isabella Bay in Niginganiq National Wildlife Area is the first wildlife sanctuary in the world to be designed specially for Bowhead whales. However, moultings have not been recorded in this area due to environmental factors.[66]

Predation

The principal predators of bowheads are humans.[12] Killer whales are also known predators. The swimming pattern and behavior of bowhead whales are influenced by the fear of killer whales. This fear causes the bowhead to seek cover in ice and shallow waters when threatened.[18]

Whaling

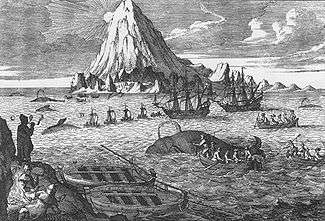

The bowhead whale has been hunted for blubber, meat, oil, bones, and baleen. Like right whales, it swims slowly, and floats after death, making it ideal for whaling.[13] Before commercial whaling, they were estimated to number 50,000.

Commercial bowhead whaling began in the 16th century,[13] when the Basques killed them as they migrated south through the Strait of Belle Isle in the fall and early winter. In 1611, the first whaling expedition sailed to Spitsbergen. By mid-century, the population(s) there had practically been wiped out, forcing whalers to voyage into the "West Ice"—the pack ice off Greenland's east coast. By 1719, they had reached the Davis Strait, and by the first quarter of the 19th century, Baffin Bay.[67]

In the North Pacific, the first bowheads were taken off the eastern coast of Kamchatka by the Danish whaleship Neptun, Captain Thomas Sodring, in 1845. In 1847, the first bowheads were caught in the Sea of Okhotsk, and the following year, Captain Thomas Welcome Roys, in the bark Superior, of Sag Harbor, caught the first bowheads in the Bering Strait region. By 1849, 50 ships were hunting bowheads in each area. By 1852, 220 ships were cruising around the Bering Strait region, which killed over 2,600 whales. Between 1854 and 1857, the fleet shifted to the Sea of Okhotsk, where 100–160 ships cruised annually. During 1858–1860, the ships shifted back to the Bering Strait region, where the majority of the fleet would cruise during the summer up until the early 20th century. An estimated 18,600 bowheads were killed in the Bering Strait region between 1848 and 1914, with 60% of the total being reached within the first two decades. An estimated 18,000 bowheads were killed in the Sea of Okhotsk during 1847–1867, 80% in the first decade.

Bowheads were first taken along the pack ice in the northeastern Sea of Okhotsk, then in Tausk Bay and Northeast Gulf (Shelikhov Gulf). Soon, ships expanded to the west, catching them around Iony Island and then around the Shantar Islands. In the Western Arctic, they mainly caught them in the Anadyr Gulf, the Bering Strait, and around St. Lawrence Island. They later spread to the western Beaufort Sea (1854) and the Mackenzie River delta (1889).

Commercial whaling, the principal cause of the population decline, is over. Bowhead whales are now hunted on a subsistence level by native peoples of North America.[68]

Conservation

The bowhead is listed in Appendix I by CITES (that is, "threatened with extinction"). It is listed by the National Marine Fisheries Service as "endangered" under the auspices of the United States' Endangered Species Act. The IUCN Red List data are as follows:[13]

- Svalbard population – Critically endangered

- Sea of Okhotsk subpopulation – Endangered

- Baffin Bay-Davis Strait stock – Endangered

- Hudson Bay-Foxe Basin stock – Vulnerable (Estimated to be 1,026 individuals in 2005 by DFO)[69]

- Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock – Lower risk – conservation dependent

The bowhead whale is listed in Appendix I[70] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of their range. CMS Parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration, and controlling other factors that might endanger them.[13]

Gallery

- Balaena mysticetus on Wikimedia Commons.

-

Whales swimming in Lindgolm strait (Russian: пролив Линдгольма) of Shantar Islands, northwestern Sea of Okhotsk[1]

-

Cavorting whales in northwestern part of Sea of Okhotsk[2]

-

Blowholes

-

Resting in Foxe Basin

-

Fluke up before diving

-

Whale showing one of pectoral fins

-

Tip of whitish chin visible

-

Map of the bowhead whale ranges centered over the North Pole

- ^ Vladislav Raevskii. Retrieved 1 June 2014

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Olga_Shpak._2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

See also

References

- ↑ Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R.L., Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. (2012). "Balaena mysticetus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ Rugh, David J.; Shelden, Kim E. W. (2008). "Bowhead Whale". In Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Second ed.). Academic Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- ↑ Scammon, Charles M. (1874) The Marine Mammals of the North-Western Coast of North America, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, ISBN 1597140619.

- ↑ Guinness World Records (14 November 2007). "Whale of a time!". Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. [System of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to the classes, orders, genera, species, with the characters, the differences, synonyms, places.] (in Latin) I (tenth, reformed ed.). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824.

- ↑ Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. (2012). "Balaena mysticetus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 18 October 2012. "The taxonomy is not in doubt.... Concerning common names, the species was once commonly known in the North Atlantic and adjacent Arctic as the Greenland Right Whale. However, the common name Bowhead Whale is now generally used for the species."

- ↑ Rice, Dale W. (1998). Marine mammals of the world: systematics and distribution. Society of Marine Mammalogy Special Publication No. 4. ISBN 1891276034.

- ↑ Kenney, Robert D. (2008). "Right Whales (Eubalaena glacialis, E. japonica, and E. australis)". In Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 962–969. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, H. C., R. L. Brownell Jr.; M. W. Brown C. Schaeff, V. Portway, B. N. White, S. Malik, L. A. Pastene, N. J. Patenaude, C. S. Baker, M. Goto, P. Best, P. J. Clapham, P. Hamilton, M. Moore, R. Payne, V. Rowntree, C. T. Tynan, J. L. Bannister and R. Desalle (2000). "World-wide genetic differentiation of Eubalaena: Questioning the number of right whale species" (PDF). Molecular Ecology 9 (11): 1793–802. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01066.x. PMID 11091315.

- ↑ "Whale bones found in highway were not from mystery whale". ScienceNordic.com. 7 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bowhead Whale. The Kids’ Times: Volume II, Issue 2. NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources (2011)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ Scoresby, William (1820). An Account of the Arctic Regions with a History and a Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery. Edinburgh.

- ↑ Koski, William R., Rolph A. Davis, Gary W. Miller, and David E. Withrow (1993). "Reproduction". In Burns, J. J.; Montague, J. J.; and Cowles, C. J. The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No. 2: The Society for Marine Mammalogy. p. 245.

- ↑ Eilperin, Juliet (18 October 2012). "Bowhead whales lost genetic diversity, study shows". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Ford Jr, T. J.; Werth, A. J.; George, J. C. (2013). "An intraoral thermoregulatory organ in the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus), the corpus cavernosum maxillaris". Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007) 296 (4): 701–708. doi:10.1002/ar.22681. PMID 23450839.

- 1 2 3 4 Finley, K.J. (2001). "Natural History and Conservation of the Greenland Whale, or Bowhead, in the Northeast Atlantic". Artic Institute of North America 54 (1): 55–76.

- 1 2 3 Simmon, Malene; Johnson, Mark; Tyack, Peter ; Madsen, Peter T. (2009). "Behaviour and Kinematics of Continuous Ram Filtration in BowheadWhales (Balaena mysticetus)". Biological Sciences 276 (1674): 3819–3828. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1135.

- 1 2 Bowhead Whale. American Cetacean Society. Retrieved on 16 November 2015.

- ↑ Schiffman, Joshua D.; Breen, Matthew (2015). "Comparative oncology: what dogs and other species can teach us about humans with cancer". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370 (1673): 1–13. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0231.

- ↑ George, John C.; Bada, Jeffrey; Zeh, Judith; Scott, Laura; Brown, Stephen E.; O'Hara, Todd and Suydam, Robert (1999). "Age and growth estimates of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) via aspartic acid racemization". Can. J. Zool. 77 (4): 571–580. doi:10.1139/z99-015.

- ↑ Conroy, Erin. (6 December 2007) Netted whale hit by lance a century ago. MSNBC.

- ↑ 19th-century weapon found in whale. Associated Press via USA Today. 12 June 2007

- ↑ "Can Marine Biology Help Us Live Forever? Bowhead Whale Can Live 200 Years, Is Cancer Resistant". Medical Daily. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Researchers hope this whale’s genes will help reverse human aging". The Washington Post. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Scientists map bowhead whale’s genome; discover genes responsible for long life". Technie News. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ "The bowhead whale lives over 200 years. Can its genes tell us why?". Science Daily. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Smultea, M.; Fertl, D.; Rugh, D. J.; Bacon, C. E. (2012). Summary of systematic bowhead surveys conducted in the U.S. Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, 1975–2009. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-237. p. 48.

- ↑ Foote, A. D.; Kaschner, K.; Schultze, S. E.; Garilao, C.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Post, K.; Higham, T. F. G.; Stokowska, C.; Van Der Es, H.; Embling, C. B.; Gregersen, K.; Johansson, F.; Willerslev, E.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2013). "Ancient DNA reveals that bowhead whale lineages survived Late Pleistocene climate change and habitat shifts". Nature Communications 4: 1677. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4E1677F. doi:10.1038/ncomms2714. PMID 23575681.

- 1 2 Norwegian Polar Institute. Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus). npolar.no

- ↑ Eastern Arctic bowhead whales not threatened. Cbc.ca (16 April 2008). Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- ↑ Laidre, Kristin (22 January 2009) "Foraging Ecology of Bowhead Whales in West Greenland." Monster Jam. Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Seattle.

- 1 2 http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-90-481-9121-5_8#page-1

- ↑ http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=131

- 1 2 http://www.nwmb.com/iku/2013-11-09-01-41-51/2013-11-09-01-46-43/2008/mar-06-2008-level-of-tah-for-bowhead-whales/551-tab15-df0-1999/file

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_bowhead_whale_e.pdf

- ↑ http://arctic.blogs.panda.org/field/june-2014-bowheads-and-breaking-ice/

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10155443054575618&set=gm.710350395741959&type=3

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10153944981420618&set=gm.517614455015555&type=3&theater

- ↑ http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/coe-cde/cemam/themes/dynami-fra.htm

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/groups/333634176654762/permalink/824164764268365/

- ↑ http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic36-1-5.pdf

- ↑ http://churchillpolarbears.org/2015/07/bowhead-whale-in-churchill-waters/

- 1 2 3 Shpak, Olga (19 February 2014). "Второе рождение гренландского кита" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "Тур 'наблюдение за китами и плавание вдоль побережья Охотского моря и на Шантарските острова'" (in Russian). Arcticexpedition.ru. 15 August 2000. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ "Фотография: Киты подходят совсем близко к берегу" (in Russian). Turizmvnn.ru. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ "WWF приветствует создание нацпарка в Хабаровском крае" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0034905#pone-0034905-g002

- ↑ http://osakagyoren.or.jp/naniwa/

- ↑ http://www.asahi.com/articles/ASH6R5VQ2H6RIIPE026.html

- ↑ http://www.city.ishikari.hokkaido.jp/soshiki/bunkazaih/2785.html

- ↑ Gross A., 2010 Background Document for Bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus. The OSPAR Convention and Musée des Matériaux du Centre de Recherche sur les Monuments Historiques. ISBN 978-1-907390-35-7. retrieved on 24 May 2014

- ↑ Kovacs M.K., Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus). Environmental Monitoring of Svalbard and Jan Mayen. retrieved on 27 May 2014

- ↑ Gilg O.; Born W.E. (2004). "Recent sightings of the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) in Northeast Greenland and the Greenland Sea". Polar Biology 28 (10): 796. doi:10.1007/s00300-005-0001-9.

- ↑ Ritchie B. (June 2013) Arctic shorts – bowhead whale. Vimeo. Retrieved 2 June 2014

- ↑ Sala E., 2013 Franz Josef Land Expedition: First Look at Post-Expedition Discoveries. Pristine Seas Expeditions. National Geographic. retrieved on 24 May 2014

- ↑ WIIG Ø., Bachmann L., Janik M.V., Kovacs M.K., Lydersen C., 2007. Spitsbergen Bowhead Whales Revisited. Society for Marine Mammalogy. Retrieved 24 May 2014

- ↑ Johannessen, R. (19 October 2011) Dette er en sensasjon!. The Aftenposten. retrieved on 27 May 2014

- ↑ Nefedova T., Gavrilo M., Gorshkov S., 2013. Летом в Арктике стало меньше льда. Russian Geographical Society. retrieved on 24 May 2014

- ↑ European Cetacean Society. Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) sighting in the Franz Josef Land area.. retrieved on 24 May 2014

- ↑ Scalini I. (19 February 2014) Всемирный день китов. Russian Arctic National Park. retrieved on 24 May 2014

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150721-secret-whale-refuge-discovered

- ↑ https://oceanwide-expeditions.com/blog/exceptional-sighting-of-80-bowhead-whales

- ↑ Lennartz T. (29 April 2013) New Bowhead Whale Molting Location Found. Arctic Kingdom. retrieved on 9 June 2014

- ↑ Polar Bears and Glaciers of Baffin Island Webinar on Vimeo. Arctic Kingdom. 2014. retrieved on 9 June 2014

- ↑ Beach, Frederick Converse (1 January 1910). The Americana: a universal reference library, comprising the arts and sciences, literature, history, biography, geography, commerce, etc., of the world. Scientific American. p. 667.

- ↑ "Bowhead Whale". WWF. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Bowhead Whale, Walrus and Polar Bears of Foxe Basin on Vimeo. Arctic Kingdom. 2011. retrieved on 9 June 2014

- ↑ "Appendix I" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005, and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balaena mysticetus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Balaena mysticetus |

- "Bowhead whale: 200 year old whales". BBC Ocean Giants. Retrieved October 2013.

- "The Bowhead Whale". Voices in the Sea, University of California San Diego. Retrieved October 2013.

- "Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus)". Office of Protected Resources, NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved October 2013.

- "Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus)". ARKive. Retrieved October 2013.

- "Harpoon may prove whale was at least 115 years old". World History Blog. Retrieved October 2013.

- "In Search of the Bowhead Whale". NFB.ca. Retrieved October 2013. A documentary by Bill Mason from 1974 following an expedition that searches out and meets the bowhead and beluga.