Boundary layer thickness

This page describes some parameters used to measure the properties of boundary layers. Consider a stationary body with a turbulent flow moving around it, like the semi-infinite flat plate with air flowing over the top of the plate. At the solid walls of the body the fluid satisfies a no-slip boundary condition and has zero velocity, but as you move away from the wall, the velocity of the flow asymptotically approaches the free stream mean velocity. Therefore it is impossible to define a sharp point at which the boundary layer becomes the free stream, yet this layer has a well-defined characteristic thickness. The parameters below provide a useful definition of this characteristic, measurable thickness.

Motivations for boundary layers

As the Navier-Stokes equations that describe the motion of fluids are not solved in the general case, simplifying assumptions are used to describe approximate behaviour. For a fluid of low viscosity (compared to the geometrical configuration of the problem), the Reynolds number is large and the viscous term in the Navier-Stokes equation is small compared to the inertial term in much of the space. However, this is not true near the boundaries of the fluid and this description fails to capture some important behavior in a lot of real systems, for instance the Kármán vortex street or the drag force on an airplane wing.

99% Boundary Layer thickness

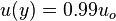

The boundary layer thickness, δ, is the distance across a boundary layer from the wall to a point where the flow velocity has essentially reached the 'free stream' velocity,  . This distance is defined normal to the wall, and the point where the flow velocity is essentially that of the free stream is customarily defined as the point where:

. This distance is defined normal to the wall, and the point where the flow velocity is essentially that of the free stream is customarily defined as the point where:

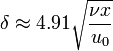

For laminar boundary layers over a flat plate, the Blasius solution gives:

For turbulent boundary layers over a flat plate, the boundary layer thickness is given by:

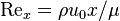

where

is the overall thickness (or height) of the boundary layer

is the overall thickness (or height) of the boundary layer is the Reynolds Number

is the Reynolds Number is the density

is the density is the freestream velocity

is the freestream velocity is the distance downstream from the start of the boundary layer

is the distance downstream from the start of the boundary layer is the kinematic viscosity

is the kinematic viscosity is the dynamic viscosity

is the dynamic viscosity

The velocity thickness can also be referred to as the Soole ratio, although the gradient of the thickness over distance would be adversely proportional to that of velocity thickness.

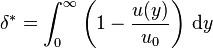

Displacement thickness

The displacement thickness, δ* or δ1 is the distance by which a surface would have to be moved in the direction perpendicular to its normal vector away from the reference plane in an inviscid fluid stream of velocity  to give the same flow rate as occurs between the surface and the reference plane in a real fluid.[1]

to give the same flow rate as occurs between the surface and the reference plane in a real fluid.[1]

In practical aerodynamics, the displacement thickness essentially modifies the shape of a body immersed in a fluid to allow an inviscid solution. It is commonly used in aerodynamics to overcome the difficulty inherent in the fact that the fluid velocity in the boundary layer approaches asymptotically to the free stream value as distance from the wall increases at any given location.

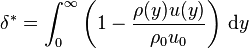

The definition of the displacement thickness for compressible flow is based on mass flow rate:

The definition for incompressible flow can be based on volumetric flow rate, as the density is constant:

Where  and

and  are the density and velocity in the 'free stream' outside the boundary layer, and

are the density and velocity in the 'free stream' outside the boundary layer, and  is the coordinate normal to the wall.

is the coordinate normal to the wall.

For laminar boundary layers over a flat plate, the Blasius solution gives:

For boundary layer calculations, the density and velocity at the edge of the boundary layer must be used, as there is no free stream. In the equations above,  and

and  are therefore replaced with

are therefore replaced with  and

and  .

.

The displacement thickness is used to calculate the boundary layer's shape factor.

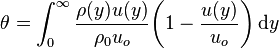

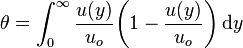

Momentum thickness

The momentum thickness, θ or δ2, is the distance by which a surface would have to be moved parallel to itself towards the reference plane in an inviscid fluid stream of velocity  to give the same total momentum as exists between the surface and the reference plane in a real fluid.[1]

to give the same total momentum as exists between the surface and the reference plane in a real fluid.[1]

The definition of the momentum thickness for compressible flow is based on mass flow rate:

The definition for incompressible flow can be based on volumetric flow rate, as the density is constant:

Where  and

and  are the density and velocity in the 'free stream' outside the boundary layer, and

are the density and velocity in the 'free stream' outside the boundary layer, and  is the coordinate normal to the wall.

is the coordinate normal to the wall.

For boundary layer calculations, the density and velocity at the edge of the boundary layer must be used, as there is no free stream. In the equations above,  and

and  are therefore replaced with

are therefore replaced with  and

and  .

.

For a flat plate at no angle of attack with a laminar boundary layer, the Blasius solution gives

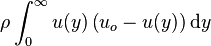

The influence of fluid viscosity creates a wall shear stress,  , which extracts energy from the mean flow. The boundary layer can be considered to possess a total momentum flux deficit, due to the frictional dissipation.

, which extracts energy from the mean flow. The boundary layer can be considered to possess a total momentum flux deficit, due to the frictional dissipation.

Other length scales describing viscous boundary layers include the energy thickness,  .

.

Shape factor

A shape factor is used in boundary layer flow to determine the nature of the flow.

where H is the shape factor,  is the displacement thickness and θ is the momentum thickness. The higher the value of H, the stronger the adverse pressure gradient. A high adverse pressure gradient can greatly reduce the Reynolds number at which transition into turbulence may occur.

is the displacement thickness and θ is the momentum thickness. The higher the value of H, the stronger the adverse pressure gradient. A high adverse pressure gradient can greatly reduce the Reynolds number at which transition into turbulence may occur.

Conventionally, H = 2.59 (Blasius boundary layer) is typical of laminar flows, while H = 1.3 - 1.4 is typical of turbulent flows.

Further reading

- F.M. White, "Fluid Mechanics", McGraw-Hill, 5th Edition, 2003.

- B.R. Munson, D.F. Young and T.H. Okiishi, "Fundamentals of Fluid Mechanics", John Wiley, 4th Edition, 2002.

- B. Massey and J. Ward-Smith, "Mechanics of Fluids", Taylor and Francis, 8th Edition, 2006.