Croat–Bosniak War

| Croat–Bosniak War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War | |||||||||

A war-ravaged street in Mostar during the conflict. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

(HVO military police) |

(Croatian Defence Forces) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 50,000 soldiers | 80,000 soldiers | ||||||||

The Croat–Bosniak War was a conflict between the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the self-proclaimed Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, supported by Croatia, that lasted from 19 June 1992[3] – 23 February 1994. The Croat-Bosniak war is often referred to as a "war within a war" because it was part of the larger Bosnian War. Although initially on the same side,[4] at the end of 1992, tensions between Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks rose and their collaboration fell apart. In January 1993, the two former allies engaged in open conflict.[5] On 23 February 1994 a ceasefire was reached and an agreement ending the hostilities was signed in Washington on 18 March 1994.[6][7] Due to the involvement of Croatia's armed forces which supported Bosnian Croats, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) effectively determined the war's nature to be international between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in numerous verdicts against Bosnian Croat political and military leaders.[8]

The ICTY found that in the trial against the leadership of the Croatian Defence Council and Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia that "evidence showed that troops of the Croatian Army fought alongside the HVO against the ABiH and that the Republic of Croatia had overall control over the armed forces and the civilian authorities of the Croatian Community (and later Republic) of Herzeg-Bosna. The Chamber, by a majority, found that a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) existed and had as its ultimate goal the establishment of a Croatian territorial entity with part of the borders of the Croatian Banovina of 1939 to enable a reunification of the Croatian people. This Croatian territorial entity in BiH was either to be united with Croatia following the prospective dissolution of BiH, or become an independent state within BiH with direct ties to Croatia."[9]

Background

In 1990 and 1991, Serbs in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina had proclaimed a number of "Serbian Autonomous Regions" with the intent of later unifying them to create a Greater Serbia. Serbs used the well equipped Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) in defending these territories.[10] As early as September or October 1990, the JNA had begun arming Bosnian Serbs and organizing them into militias. By March 1991, the JNA had distributed an estimated 51,900 firearms to Serb paramilitaries and 23,298 firearms to Serbian Democratic Party (SDS).[11] The Croatian government began arming Croats in the Herzegovina region in 1991 and in the start of 1992, expecting that the Serbs would spread the war into Bosnia and Herzegovina.[12] It also helped arm the Bosniak community. From July 1991 to January 1992, the JNA and Serb paramilitaries used Bosnian territory to wage attacks on Croatia.[13]

On 25 March 1991, Franjo Tuđman met with Serbian president Slobodan Milošević in Karađorđevo, reportedly to discuss partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[14][15] In November, the autonomous Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia (HZ-HB) was established, it claimed it had no secessionary goal and that it would serve a "legal basis for local self-administration". It vowed to respect the Bosnian government under the condition that Bosnia and Herzegovina was independent of "the former and every kind of future Yugoslavia."[16] On 12 November 1991, numerous leading members of the Bosnian branch of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) drafted a document that stated, among other things, that "... the Croat people in Bosnia-Herzegovina must finally undertake a decisive and active policy that should bring about the realisation of our centuries-old dream: a common Croatian state." It was signed by Mate Boban, Vladimir Šoljić, Božo Raić, Ivan Bender, Pero Marković, Dario Kordić and others.[17][18] In December, Tuđman, in a conversation with Bosnian Croat leaders, said that "from the perspective of sovereignty, Bosnia-Herzegovina has no prospects" and recommended that Croatian policy "support for the sovereignty [of Bosnia and Herzegovina] until such time as it no longer suits Croatia."[19]

On 29 February and 1 March 1992 an independence referendum was held in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Independence was strongly favored by Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, while Bosnian Serbs largely boycotted the referendum. The majority of voters voted for independence and on 3 March 1992 Alija Izetbegović declared independence of the country, which was immediately recognised by Croatia.[20][21] Following the declaration of independence, the Serbs attacked different parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The state administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina effectively ceased to function having lost control over the entire territory.[22] In April 1992, the siege of Sarajevo began, by which time the Bosnian Serb-formed Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) controlled 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[23] On 8 April, Bosnian Croats were organized into the Croatian Defence Council (HVO).[15] A sizable number of Bosniaks also joined.[12] The Croatian Defence Forces (HOS), led by Blaž Kraljević in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which "supported Bosnian territorial integrity much more consistently and sincerely than the HVO" was also created.[12] On 15 April 1992, the multi-ethnic Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) was formed, with slightly over two-thirds of troops consisting of Bosniaks and almost one-third of Croats and Serbs.[24] In the winter Bosniaks began leaving the HVO and joining the ARBiH which also began receiving supplies from Croatia.[15] In May, HVO Major General Ante Roso declared that the only "legal military force" in HZ-HB was the HVO and that "all orders from the TO [Territorial Defense] command [of Bosnia and Herzegovina] are invalid, and are to be considered illegal on this territory".[25]

The Croatian government played a "double game"[19] in Bosnia and Herzegovina and "a military solution required Bosnia as an ally, but a diplomatic solution required Bosnia as a victim".[26] Tuđman's HDZ party held important positions in the Bosnian government including the premiership and the ministry of defence, but despite this carried out a separate policy and refused for the HVO to be integrated into ARBiH.[24] Jerko Doko, the Bosnian defence minister, gave the HVO priority in the acquisition of military weapons.[24] In January 1992, Croatian president Franjo Tuđman arranged for Stjepan Kljuić, president of the Bosnian branch of the HDZ who favored cooperating with the Bosniaks towards a unified Bosnian state, to be ousted and replaced by Mate Boban, who favored Croatia to annex Croat-inhabited parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[27][15] A rift existed in the party between Croats from ethnically mixed areas of central and northern Bosnia and those from Herzegovina.[28] Milivoj Gagro, prewar Croat mayor of Mostar and ally of Kljuić said: "The secessionist policy [union with Croatia] was consistently supported by the Herzegovina side, not by Sarajevo, Posavina, or Central Bosnia Croats. [...] Croats from Central Bosnia and Posavina, as well as those from urban centers who lived with Muslims and Serbs, thought differently. But when the war picked up, Posavina Croats were attacked, Sarajevo was surrounded [...] Kljuić was sidelined and Boban came in with idea [the Croat separatist idea] in this area. [...] When they [Croats in Sarajevo as well as Northern and Central Bosnia] felt they could not survive any more they lifted their hands and accepted their fate. And the Herzegovina Croats promised them the stars in the sky and told them "come here and we will give you a place." And what happened? It resulted in an exodus. And all these miserable Croat refugee communities that look absolutely ugly."[29]

On 10 April 1992, Mate Boban decreed that the Bosnian Territorial Defence (TO), which had been created the day before, was illegal on territory of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia. In May 1992 Tihomir Blaškić and Major General Ante Roso also declared the TO illegal. Roso declared that the HVO was the only legal military force in Herzeg-Bosnia (the area controlled by the HVO).[30][31] On 9 May, Boban, Josip Manolić,[32] Izetbegović came under intense pressure from Tuđman to agree for Bosnia and Herzegovina to be in a confederation with Croatia; however, Izetbegović wanted to prevent Bosnia and Herzegovina from coming under the influence of Croatia or Serbia. Because doing so would cripple reconciliation between Bosniaks and Serbs, make the return of Bosniak refugees to eastern Bosnia impossible and for other reasons, Izetbegović opposed. He received an ultimatum from Boban warning that if he did not proclaim a confederation with Tuđman that Croatian forces would not help defend Sarajevo from strongholds as close as 40 kilometres (25 mi) away.[33] On 9 May, Boban, Josip Manolić,[32] Tuđman's aide and previously the Croatian Prime Minister, and Radovan Karadžić, president of the self-proclaimed Republika Srpska, secretly met in Graz and formed an agreement on the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Graz agreement.[34][35] However, the parties ultimately parted ways without signing any agreement and clashes between the two sides continued.[36][37] Beginning in June, discussions between Bosniaks and Croats over military cooperation and possible merger of their armies started to take place.[38] The Croatian government recommended moving ARBiH headquarters out of Sarajevo and closer to Croatia and pushed for its reorganization in an effort to heavily add Croatian influence.[39]

In June 1992 efforts of the HVO to gain control of Novi Travnik and Gornji Vakuf were resisted. On 18 June 1992 the Bosnian Territorial Defence in Novi Travnik received an ultimatum from the HVO which included demands to abolish existing Bosnia and Herzegovina institutions, establish the authority of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia and pledge allegiance to it, subordinate the Territorial Defense to the HVO and expel Muslim refugees, all within 24 hours. The attack was launched on 19 June. The elementary school and the Post Office were attacked and damaged.[3] Boban increased pressure "by blocking delivery of arms that the Sarajevo government, working around a United Nations embargo on all shipments to the former Yugoslavia, has secretly bought."[40] On 3 July, Boban declared the independence of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia (HR-HB).[41][33] He was established as its president.[32] It claimed power over its own police, army, currency, and education and extended its grasp to many districts where Bosniaks were the majority. It only allowed a Croat flag to be used, the only currency allowed was the Croatian kuna, its only official language was Croatian, and a Croat school curriculum was enacted. Mostar, a town where Bosniaks constituted a slight majority, was set as the capital.[42] There was no mention on the defense of Bosnia and Herzegovina's territorial integrity.[43]

On 21 July, Izetbegović and Tuđman signed the Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia in Zagreb, Croatia.[44] The agreement allowed them to "cooperate in opposing [the Serb] aggression" and coordinate military efforts.[45] It placed the HVO under the command of the ARBiH.[46] Cooperation was inharmonious, but enabled the transportation of weapons to ARBiH through Croatia in spite of the UN sanctioned arms embargo,[12] reopening channels blocked by Boban.[39] It established "economic, financial, cultural, educational, scientific and religious cooperation" between the signatories. It also stipulated that Bosnian Croats hold dual citizenship for both Bosnia and Herzegovina and for Croatia. This was criticized as Croatian attempts at "claiming broader political and territorial rights in the parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina where large numbers of Croats live". After its signature Boban vowed to Izetbegović that HR-HB would remain an integral part of Bosnia and Herzegovina when the war ended.[39]

In the summer of 1992, the HVO started to purge its Bosniak members.[47] At the same time armed incidents started to occur among Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina between the HVO and the HOS.[48] The HOS was loyal to the Bosnian government and accepted subordination to the Staff of the ARBiH of which Kraljević was appointed a member.[49] On 9 August, Kraljević and eight of his staff were assassinated by HVO soldiers under the command of Mladen Naletilić,[27] who supported a split between Croat and Bosniaks,[50] after Kraljević's HOS attacked the VRS near Trebinje.[51] The HOS's advance into eastern Herzegovina and occupation of Trebinje angered Boban who had affirmed to Karadžić that Croat forces were uninterested in the region.[52] The HOS was disbanded, leaving the HVO as the only Croat force.[53] Bosnian officials suspected that Tuđman's government was involved.[51] According to Manolić the order to kill Kraljević was given by Šušak and approved by Tuđman. Božidar Vučurević, the war-time mayor of Trebinje, stated he safeguarded records showing that SDS and HDZ figures considered it a "task" that need to be carried out.[54]

On 7 September 1992, HVO demanded that the Bosniak militiamen withdraw from Croatian suburbs of Stup, Bare, Azići, Otes, Dogladi and parts of Nedzarici in Sarajevo and issued an ultimatum.[55] They denied that it was a general threat to Bosnian government forces throughout the country and claimed that Bosniak militiamen killed six of their soldiers, and looted and torched houses in Stup. The Bosniaks stated that the local Croatian warlord made an arrangement with Serb commanders to allow Serb and Croat civilians to be evacuated, often for ransom, but not Bosniaks.[56] In late September, Izetbegović and Tuđman met again and attempted to create military coordination against the VRS, but to no avail.[25] By October, the agreement had collapsed and afterwards Croatia diverted delivery of weaponry to Bosnia and Herzegovina by seizing a significant amount for itself.[57] Boban had abandoned a Bosnian government alliance and ceased all hostilities with Karadžić.[58]

The dominant Croatian–Bosnian defense of Posavina fell apart after Tuđman and/or Gojko Šušak[59][60] ordered the withdrawal of the Croatian Army (HV), enabling the Serbs to gain control of the corridor and connect their captured territories in western and eastern Bosnia.[61] On 8 October, the town of Bosanski Brod was abandoned by the HVO and left to the VRS.[61] By that time, the HV and the HVO had sustained approximately 7,500 casualties,[62] out of 20,000 troops committed to the battle to control Posavina[63] which was conducted by the VRS against HV and HVO forces to secure an open road between Belgrade, Banja Luka and Knin.[42] The pullout appeared to be a quid pro quo for the JNA withdrawal from Dubrovnik's hinterland that took place in July.[61][64] Still, a Central Intelligence Agency analysis concluded that there is no direct evidence of such arrangements.[65] On 9 October, the HVO signed a cease-fire with the VRS in Jajce in exchange for providing electricity.[25]

VRS forces captured Modriča on 28 June, Derventa on 4–5 July and Odžak on 12 July. The outnumbered Croat forces were reduced to isolated positions in Bosanski Brod and Orašje, but were able to repel VRS attacks during August and September. In early October 1992, VRS managed to break through Croat lines and capture Bosanski Brod. HV/HVO withdrew their troops north across the Sava River.[66] The rapid fall of Bosanski Brod raised speculations about its cause. The Bosnian government suspected that a Croat-Serb cease-fire was brokered, but Croat attacks on the VRS positions in the area increased after the fall of Bosanski Brod and they were able to repel a VRS offensive on Orašje in November.[67] The VRS successes in northern Bosnia resulted in increasing numbers of Bosniak refugees fleeing south towards the HVO-held regions of central Bosnia. In Bugojno and Travnik, Croats found themselves reduced practically overnight from around half the local population to a small minority.[42]

In the latter half of 1992, foreign Mujahideen hailing mainly from North Africa and the Middle East began to arrive in central Bosnia and set up camps for combatant training with the intent of helping their "Muslim brothers" against the Serbs.[68] These foreign volunteers were primarily organized into an umbrella detachment of the 7th Muslim Brigade (made up of native Bosniaks) of the ARBiH in Zenica.[69] Initially, the Mujahideen gave basic necessities including food to local Muslims.[68] When the Croat–Bosniak conflict began they joined the ARBiH in battles against the HVO.[68]

The strained relations escalated rapidly and led to an armed clash between the two forces in Novi Travnik on 18 October. Low-scale conflicts spread in the region,[70] and the two forces engaged each other along the supply route to Jajce three days later, on 21 October,[71] as a result of an ARBiH roadblock set up the previous day on authority of the "Coordinating Committee for the Protection of Muslims" rather than the ARBiH command. Just as the roadblock was dismantled,[72] a new skirmish occurred in the town of Vitez the following day.[73] On 29 October, the VRS captured Jajce due to the inability of ARBiH and HVO forces to construct a cooperative defense, [61] against the VRS which held the advantage in troop size and firepower, staff work and planning was significantly superior to the defenders of Jajce.[74] Six days prior the first major battle in the impending Croat–Bosniak war broke out when the HVO pushed ARBiH from Prozor and expelled the Bosniak population[61] after carrying out rapes, attacking the local mosque, and torching the property of Bosniaks.[58] Initial reports indicated about 300 Bosniaks were killed or wounded in the attack,[75] but subsequent reports by the ARBiH made in November 1992 indicated eleven soldiers and three civilians were killed. Another ARBiH report, prepared in March 1993, revised the numbers saying eight civilians and three ARBiH soldiers were killed, while 13 troops and 10 civilians were wounded.[76] Around 5,000 Muslims fled from Prozor, but they began to return gradually a few days of weeks after the fighting had stopped.[73][77]

By November 1992, the HVO controlled about 20 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[31] By December 1992, much of Central Bosnia was in the hands of the Croats. The Croat forces had taken control of the municipalities of the Lašva Valley and had only met significant opposition in Novi Travnik and Ahmići.[78] Bosniak authorities forbade Croats from leaving towns such as Bugojno and Zenica, and would periodically organise exchanges of local Croats for Muslims.[69]

The ICTY Trial Chamber in the Kordić and Čerkez case decided that the weight of the evidence points clearly to the persecution of Bosniak civilians in the Central Bosnian municipalities taken over by the Croat forces: Busovača, Novi Travnik, Vareš, Kiseljak, Vitez, Kreševo and Žepče. The persecution followed a consistent pattern in each municipality and demonstrated that the HVO had launched a campaign against the Bosniaks in them[79] with the hope that the self-proclaimed Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia should secede from Bosnia and Herzegovina and with a view towards unification with Croatia.[80]

The HVO and the Bosnian Army (ARBiH) continued to fight side by side against the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) in some areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even though armed confrontation in central Bosnia strained the relationship between the HVO and ARBiH, the Croat-Bosniak alliance held in the Bihać pocket (northwest Bosnia) and the Bosanska Posavina (north), in which both were heavily outmatched by Serb forces.

Chronology

Gornji Vakuf shelling

On January 1993 Croat forces attacked Gornji Vakuf again in order to connect Herzegovina with Central Bosnia.[81] Gornji Vakuf is a town to the south of the Lašva Valley and of strategic importance at a crossroads en route to Central Bosnia. It is 48 kilometres from Novi Travnik and about one hour's drive from Vitez in an armoured vehicle. For Croats it was a very important connection between the Lašva Valley and Herzegovina, two territories included in the self-proclaimed Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia. The Croat forces shelling reduced much of the historical oriental center of the town of Gornji Vakuf to rubble.[82]

On 10 January 1993, just before the outbreak of hostilities in Gornji Vakuf, the Croat Defence Council (HVO) commander Luka Šekerija, sent a "Military – Top Secret" request to Colonel Tihomir Blaškić and Dario Kordić, (later convicted by ICTY of war crimes and crimes against humanity i.e. ethnic cleansing) for rounds of mortar shells available at the ammunition factory in Vitez.[83] Fighting then broke out in Gornji Vakuf on 11 January 1993, sparked by a bomb which had been placed by Croats in a Bosniak-owned hotel that had been used as a military headquarters. A general outbreak of fighting followed and there was heavy shelling of the town that night by Croat artillery.[84]

During cease-fire negotiations at the Britbat HQ in Gornji Vakuf, colonel Andrić, representing the HVO, demanded that the Bosnian forces lay down their arms and accept HVO control of the town, threatening that if they did not agree he would flatten Gornji Vakuf to the ground.[85][86] The HVO demands were not accepted by the Bosnian Army and the attack continued, followed by massacres on Bosnian Muslim civilians in the neighbouring villages of Bistrica, Uzričje, Duša (see also Duša massacre, Ždrimci and Hrasnica.[87][88] During the Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing it was surrounded by Croatian Army and Croatian Defence Council for seven months and attacked with heavy artillery and other weapons (tanks and snipers). Although Croats often cited it as a major reason for the attack on Gornji Vakuf, the commander of the British Britbat company claimed that there were no Muslim holy warriors in Gornji Vakuf (commonly known as Mujahideen) and that his soldiers had not seen any. The shelling campaign and the attackes during the war resulted in hundreds of either injured or killed, mostly Bosnian Muslim civilians.[82]

On the morning of 25 January 1993, Croat forces attacked the Bosniak part of the town of Busovača called Kadića Strana following the 20 January ultimatum. The attack included shelling from the surrounding hills. A loudspeaker called on Bosniaks to surrender. A police report shows that 43 people were massacred in Busovača in January and February 1993. The remaining Bosniaks (around 90 in all) were rounded up in the town square. Women and children (around 20 in total) were allowed to return home and the men (70 in all), some as young as 14–16 years, were loaded onto buses and taken to Kaonik camp. The violence continued after the January attack.[89]

April 1993 in central Bosnia

According to unverified claims on April 13, 1993 four members of the HVO brigade Stjepan Tomašević were seized outside Novi Travnik. The four kidnapped personnel included Vlado Slišković, deputy commander of the Tomasević Brigade; Ivica Kambić, the brigade SIS officer; Zdravko Kovač, the brigade intelligence officer; and their driver, Mire Jurkević. The kidnapped HVO soldiers were allegedly bound, gagged, and blindfolded and remained so for most of their captivity.[90]

On April 15, 1993, the head of the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) Military Police in Zenica Živko Totić was kidnapped abducted by a group of unknown Muslim assailants while en route to his headquarters. A testimony at the ICTY stated that on April 15, 1993 masked attackers wearing Bosnian Army insignias blocked his car in a Zenica suburb and killed his driver, two bodyguards and his brother-in-law, all with him in the car-as well as a passer-by. Having killed his escort, the assailants tied Totić up, placed a transparent black bag over his head, threw him into a van and drove him away, yelling "Allahu Ekber."[91]

Bosnian Army quickly ordered all units to help find the kidnapped men.

The defence in the Kupreškić trial in the ICTY against Croat soldiers accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity on Bosniaks during Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing claimed that the abduction of Totić sparked the Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing.[92] However, the ICTY found that the evidence revealed a tendency on the Croat side to spread alarm among the Croat population. A videotape of a news programme reporting the kidnapping of Živko Totić, is also instructive. The broadcaster recites all the alleged crimes committed by the Bosniaks against the Croats in an apparent attempt to incite hatred against the Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Army. This vitiates Zvonimir Cilic's assertion that the Croat leadership was trying to achieve conciliation among ethnic groups, but to prepare their own population for an attack on the Bosnian Muslims creating misinformation and propaganda.[93]

During the ICTY trial of Tihomir Blaškić, the defence attorney claimed that the kidnappings were in response to HVO forces arresting and detaining 13 Bosnian Mujahideen.[94]

The ICTY Trial Chamber in the trial of Dario Kordić concluded that the Bosnian Army or the Bosniaks in general didn't plan to launch an attack on the Croats on 15–16 April 1993. Countrary, the ICTY Trial Chamber in the Kordić and Čerkez case based on the evidence of numerous HVO attacks at that time concluded that by April 1993 Croat leadership had a common design or plan conceived and executed to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley. Dario Kordić, as the local political leader, was found to be the planner and instigator of this plan.[95]

British UNPROFOR officers testified both for the prosecution and for the defence in the Blaškić trial, explaining how the tensions in the Lašva Valley and in Zenica were palpable because of numerous incidents - the Totić abduction, the arrest of two member of the ABiH Military Police in Vitez, the presence of the 7th Muslim brigade in Travnik in March and April, the Mate Boban visit to Travnik, etc.[96]

Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing

The Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing campaign against Bosniak civilians planned by the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia's political and military leadership from May 1992 to March 1993 and erupting the following April, was meant to implement objectives set forth by Croat nationalists in November 1991.[30] The Lašva Valley's Bosniaks were subjected to persecution on political, racial and religious grounds,[97] deliberately discriminated against in the context of a widespread attack on the region's civilian population[98] and suffered mass murder, rape, imprisonment in camps, as well as the destruction of cultural sites and private property. This was often followed by anti-Bosniak propaganda, particularly in the municipalities of Vitez, Busovača, Novi Travnik and Kiseljak. Ahmići massacre on 16 April 1993 was the culmination of the Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing. The village of Ahmići was attacked by surprise in the morning with mortar rounds and sniper fire. The attack resulted in mass killing of at least 103 Bosnian Muslim civilians.[99] On the same day in the village of Trusina, 18 Croat civilians and 4 soldiers were killed by the ARBiH.[100]

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has ruled that these crimes amounted to crimes against humanity in numerous verdicts against Croat political and military leaders and soldiers, most notably Dario Kordić.[101] Based on the evidence of numerous HVO attacks at that time, the ICTY Trial Chamber concluded in the Kordić and Čerkez case that by April 1993 Croat leadership had a common design or plan conceived and executed to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley. Dario Kordić, as the local political leader, was found to be the planner and instigator of this plan.[95] According to the Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Center (IDC), around 2,000 Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley are missing or were killed during this period.[102] The events inspired the British television drama serial Warriors.

War in Herzegovina

The Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia took control of many municipal governments and services in Herzegovina as well, removing or marginalising local Bosniak leaders. Herzeg-Bosnia took control of the media and imposed Croatian ideas and propaganda. Croatian symbols and currency were introduced, and Croatian curricula and the Croatian language were introduced in schools. Many Bosniaks and Serbs were removed from positions in government and private business; humanitarian aid was managed and distributed to the Bosniaks' and Serbs' disadvantage; and Bosniaks in general were increasingly harassed. Many of them were deported into concentration camps: Heliodrom, Dretelj, Gabela, Vojno and Šunje.[101][103]

According to ICTY judgment in Naletilić-Martinović case Croat forces attacked the villages of Sovici and Doljani, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of Mostar in the morning on 17 April 1993. The attack was part of a larger HVO offensive aimed at taking Jablanica, the main Bosnian Muslim dominated town in the area. The HVO commanders had calculated that they needed two days to take Jablanica. The location of Sovici was of strategic significance for the HVO as it was on the way to Jablanica. For the Bosnian Army it was a gateway to the plateau of Risovac, which could create conditions for further progression towards the Adriatic coast. The larger HVO offensive on Jablanica had already started on 15 April 1993. The artillery destroyed the upper part of Sovici. The Bosnian Army was fighting back, but at about five p.m. the Bosnian Army commander in Sovici, surrendered. Approximately 70 to 75 soldiers surrendered. In total, at least 400 Bosnian Muslim civilians were detained. The HVO advance towards Jablanica was halted after a cease-fire agreement had been negotiated.[104]

Siege of Mostar

Mostar was surrounded by the Croat forces for nine months, and much of its historic city was severely destroyed in shelling including the famous Stari Most bridge.[105] Slobodan Praljak, the commander of the Croatian Defence Council, was sentenced to twenty years in prison at the ICTY for ordering the destruction of the bridge, among other charges.[105]

Mostar was divided into a Western part, which was dominated by the Croat forces and an Eastern part where the Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was largely concentrated. However, the Bosnian Army had its headquarters in West Mostar in the basement of a building complex referred to as Vranica. In the early hours of 9 May 1993, the Croatian Defence Council attacked Mostar using artillery, mortars, heavy weapons and small arms. The HVO controlled all roads leading into Mostar and international organisations were denied access. Radio Mostar announced that all Bosniaks should hang out a white flag from their windows. The HVO attack had been well prepared and planned.[106]

The Croats took over the west side of the city and expelled thousands[105] Bosniaks from the west side into the east side of the city. The HVO shelling reduced much of the east side of Mostar to rubble. The JNA (Yugoslav Army) demolished Carinski Bridge, Titov Bridge and Lucki Bridge over the river excluding the Stari Most. HVO forces (and its smaller divisions) engaged in a mass execution, ethnic cleansing and rape on the Bosniak people of the West Mostar and its surrounds and a fierce siege and shelling campaign on the Bosnian Government run East Mostar. HVO campaign resulted in thousands of injured and killed.[105]

In April 1993 and early summer 1993, the ARBiH 3rd Corps units launched a series of attacks against the HVO. On 16 April, in the village of Trusina, members of the ARBiH unit called the Zulfikar killed 18 Croat civilians and 4 Croat soldiers.[107][108] According to witness testimony, the unit rounded up a group of Croat civilians and captured soldiers. They then bound and shot them. A member of the Zulfikar unit, Rasema Handanović, admitted taking part in the murders under orders from commander Nihad Bojadžić who ordered the killing of the prisoners and was quoted as saying "not to leave any survivors".[109]

The June 1993 Offensives

In June 1993 further fighting broke out in Central Bosnia, some of it caused by the newly revitalized Bosnian Army.[110] Further complications were caused with the incident between Croats and UNPROFOR known as The Convoy of Joy Incident. This convoy of aid supplies was made up of several hundred trucks, was seven kilometres in length and was bound for Tuzla. On 7 June 1993, two members of the delegation wrote to the European Community Monitor Mission (ECMM) at Zenica about their fears for the safety of the convoy when it reached the area of Travnik and Vitez in the light of threats made to it by Mate Boban (whom the delegation had met). As a result, the ECMM decided to monitor the convoy. The convoy then made its way to Central Bosnia and the area of Novi Travnik. There it was stopped at a roadblock formed by a large crowd of Croat women at Rankovići, north of Novi Travnik. Eight of the drivers were shot and killed, vehicles were driven away and the convoy was looted by civilians and soldiers. Eventually the convoy was released. In defending the convoy Britbat shot and killed two HVO soldiers. The ICTY Trial Chamber concluded that the crowds which stopped the Convoy of Joy were under the control of Dario Kordić and colonel Blaškić.[111]

Bosnian Army attacked the HVO in the Travnik municipality in the first week of June. By 13 June, the Bosnian Army had taken Travnik and the surrounding villages.[112] Several witnesses testified that 20,000 Croat refugees had come from Travnik as a result of the Bosnian Army offensive.[111] However, according to an ECMM Report the first reports of ethnic cleansing and destruction were exaggerated. On 8 June, there was fighting in Guča Gora with reports of atrocities and destruction, the Catholic church in flames and thousands fleeing. These reports were investigated by two ECMM monitors. They found the church still standing and the claims of destruction to be exaggerated. The movement of population was organised by the HVO. According to report dated 9 June 1993 it is the first time that the Bosnian Army have taken the military initiative against the HVO in Central Bosnia. On all other occasions the Bosnian Army have responded to HVO aggression (Gornji Vakuf, Vitez and Mostar).[113]

On 9 June 1993 HVO retaliated in Novi Travnik.[113] On 12–13 June 1993 the HVO attacked villages in the Kiseljak municipality, beginning with Tulica on 12 June resulting in the deaths of at least twelve men and women and the destruction of the village. The attack began with heavy shelling of the village followed by an infantry attack from several directions. The surviving men were loaded onto a truck and taken to Kiseljak barracks. Shortly after the attack on Tulica, the associated villages of Han Ploča and Grahovci were also subject to attack. The HVO issued an ultimatum to the Bosniaks to surrender their weapons. After the ultimatum expired, the village was shelled by the HVO and the Serb Army, and houses were set on fire. An HVO infantry attack followed. Having come into the village, HVO soldiers lined up three Bosniak men against a wall and shot them. In all 64 people were killed during the attack or after HVO capture. The ICTY Trial Chamber found that the attacks on Tulica and Han Ploca–Grahovci were part of a sustained HVO attack in which civilians were murdered and subjected to inhumane treatment.[114]

A large scale attack occurred between 7 June and 13 June 1993 within, among others, the municipalities of Kakanj, Travnik and Zenica.[115] In a music school turned detention centre, 47 Bosnian Croats were said to be held without food for the first week and in a cellar with no light for 45 days while enduring beatings; international agencies were granted very limited access to the area[69][116] In several instances, ABiH forces killed HVO troops after their surrender.[68]

Foreign fighters

Muslim volunteers from different countries arrived in the second half of 1992 with the aim of fighting for Islam and on behalf of Muslims. They were called Mujahideen.[117] In 1993, some of the groups were accused of massacres and war crimes against the Croat population in central Bosnia, including the villages of Miletici (24 April), Maljine (8 June), Doljani (27–28 June), Bistrica (August), Kriz and Uzdol (14 September), and Kopijari (21 October), with an estimated number of at least 120 killed.[69] In many cases, cruel mutilations were found on the corpses, said to be the work of the Mujahideen.[69]

On 16 September 1993 the Bosnian Army condemned the killings carried out in Kriz and Uzdol and promised to prosecute those responsible.[69] On 15 October 1993, the United Nations Special Rapporteur wrote to Izetbegović, lauding the effort and requested that the other killings be also investigated.[69] He requested to know what procedures existed to subordinate irregular troops to the Bosnian Army's command structure and what actions were used to enforce discipline.[69] On 22 October 1993, Izetbegović responded and in his letter condemned the killings and assured that an investigation had begun.[69] In 2007, Bosnia's government revoked the citizenships of hundreds of former Mujadideen.[118]

Some external fighters included British volunteers as well as other numerous individuals from the cultural area of Western Christianity, both Catholics and Protestants fought as volunteers for the Croats. Dutch, American, Irish, Polish, Australian, New Zealand, French, Swedish, German, Hungarian, Norwegian, Canadian and Finnish volunteers were organized into the Croatian 103rd (International) Infantry Brigade. There was also a special Italian unit, the Garibaldi battalion.[119] and one for the French, the groupe Jacques Doriot.[119] Volunteers from Germany and Austria were also present, fighting for the Croatian Defence Forces (HOS) paramilitary group. This armed group was organized by the Croatian Party of Rights (HSP), a right-wing party, and was disbanded by the legal Croatian authorities in late 1992. HSP's leader, Dobroslav Paraga was later charged with treason by the Croatian authorities.

Swedish Jackie Arklöv fought in Bosnia and was later charged with war crimes upon his return to Sweden. Later he confessed he committed war crimes on Bosniak civilians in the Croatian camps Heliodrom and Dretelj as a member of Croat forces.[120]

Neretva 93

In September 1993 the Bosnian Army launched an operation known as Operation Neretva '93 against the HVO on a 200 km long front from Gornji Vakuf to south of Mostar, one of its largest of the year. The ARBiH launched coordinated attacks on Croat enclaves in Lašva Valley, particularly in the Vitez area. During a simultaneous attack from the north and south, at one point the ARBiH broke through HVO lines in Vitez, but were ultimately forced back.[121]

During the night of 8/9 September, the massacre in Grabovica occurred when at least 33 Croat villagers in Grabovica were killed by members of the 9th Brigade and unidentified members of the ARBiH.[122][123] Three combatants, Nihad Vlahovljak, Haris Rajkić and Sead Karagić were convicted for taking part in the killings.[123] A few days later on 14 September, the ARBiH mounted an offensive east of Prozor. During this offensive the Uzdol massacre occurred in the village of Uzdol. 70-100 Bosnian troops infiltrated past the HVO defense lines and reached the village. After capturing the HVO command post the troops went on a killing spree.[124] It was reported that 29 Croat civilians and one prisoner of war were killed by the Prozor Independent Battalion and members of the local police force.[125]

Aftermath

The Croat-Bosniak war officially ended on 23 February 1994 when the Commander of HVO, general Ante Roso and commander of Bosnian Army, general Rasim Delić, signed a ceasefire agreement in Zagreb. In March 1994 a peace agreement mediated by the USA between the warring Croats (represented by Croatia) and Bosnia and Herzegovina was signed in Washington and Vienna. It is known as the Washington Agreement. Under this agreement, the combined territory held by the Croat and Bosnian government forces was divided into ten autonomous cantons, establishing the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the start of the war, the HVO had controlled more than 20 percent of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina; just before the signing of the Washington agreement, however, it was less than 10 percent.[1]

The Croat leadership (Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić and Berislav Pušić) were convicted by ICTY in first-instance judgement to 111 years of prison on May 29, 2013. The charges included crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva conventions and violations of the laws and customs of war. Franjo Tuđman was also designated as a part of joint criminal enterprise against Bosniak population and Bosnian and Herzegovina.[126]

Dario Kordić, political leader of Croats in Central Bosnia was convicted of the crimes against humanity in Central Bosnia i.e. ethnic cleansing and sentenced to 25 years in prison.[101]

ABiH Brigadier General Enver Hadžihasanović along with former brigade Chief of Staff and commander Amir Kubura was convicted for failing to take necessary and reasonable measures to prevent or punish several crimes committed by forces under their command in central Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1993 and the beginning of 1994. General Hadžihasanović was sentenced to three years and six months of imprisonment on 22 April 2008 by the Appeals Chamber. Kubura was sentenced to two and a half years in prison. [127][128]

Bosnian commander Sefer Halilović was charged with one count of violation of the laws and customs of war on the basis of superior criminal responsibility of the incidents during Operation Neretva '93 and found not guilty.[129] General Mehmed Alagić was indicted by the ICTY but died in 2003.[130]

Croatia's president Ivo Josipović made an official visit to Bosnia in April 2010 during which he expressed a "deep regret" for Croatia's contribution "to the deaths of people and divisions" that still exists in the Bosnia and Herzegovina.[131]

Casualties

There are no precise statistics dealing with the casualties of the Croat-Bosniak conflict along ethnic lines. The Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Center's (IDC) data from 2007 on human losses in the regions caught in the Croat-Bosniak conflict as part of the wider Bosnian War, however, can serve as a rough approximation. According to this data, in Central Bosnia most of the 10,448 documented casualties (soldiers and civilians) were Bosniaks (62%), with Croats in second (24%) and Serbs (13%) in third place. The municipalities of Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje and Bugojno also geographically located in Central Bosnia, with the 1,337 documented casualties are not included in Central Bosnia statistics, but in Vrbas region statistics. Approximately 70-80% of the casualties from Gornje Povrbasje were Bosniaks. In the region of Neretva river with 6,717 casualties, 54% were Bosniaks, 24% Serbs and 21% Croats. The casualties in those regions were mostly but not exclusively the consequence of Croat-Bosniak conflict. To a lesser extent the conflict with the Serbs also resulted in a number of casualties included in the statistics.[132]

See also

Gallery

-

Ethnic composition in 1991

-

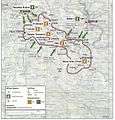

The front lines in 1994, at the end of the Bosniak-Croat war, shows only the area of war

-

The front lines in 1994, at the end of the Bosniak-Croat war and after the signing of the Washington Agreement

-

Croatian enclave in Lašva Valley, including Novi Travnik, Vitez and Busovača

-

The front lines in northern and central Herzegovina

-

Croatian enclave in northern Bosnia, including Novi Šeher and Žepče

External links

- HRW: Conflict between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia

- United States Institute of Peace: Washington Agreement

- Institute for War & Peace Reporting - Plan to Divide Bosnia Revealed

Indictments and judgments

- ICTY: Prlić et al. Initial Indictment - The Joint Criminal Enterprise (Herzeg-Bosnia case)

- ICTY: Initial indictment for the ethnic cleansing of the Lasva Valley area - Part I

- ICTY: Initial indictment for the ethnic cleansing of the Lasva Valley area - Part II

- ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict

- ICTY: Blaškić verdict

- ICTY: Aleksovski verdict

- ICTY: Miroslav Bralo verdict

- ICTY: Naletilic and Martinovic verdict

- ICTY: Hadžihasanović and Kubara verdict

- ICTY: Delić verdict

- The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Paško Ljubičić indictment

- The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Krešo Lučić indictment

Related films

- Warriors at the Internet Movie Database

- The Death of Yugoslavia at the Internet Movie Database - Part III. The Struggle for Bosnia

Notes

- 1 2 Magaš (2001), p. 66

- ↑ "IT-98-34-T, the Prosecutor versus Naletilic and Martinovic". ICTY. 17 July 2002. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- 1 2 Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 153

- ↑ Prlic et al. judgement 2013, p. 156.

- ↑ Delic judgement 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Delic judgement 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ CIA 2002b, pp. 450.

- ↑ "ICTY: Conflict between Bosnia and Croatia".

- ↑ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia Prlić et al. CIS, p. 6.

- ↑ Lukic & Lynch 1996, p. 203.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 414.

- 1 2 3 4 Goldstein 1999, p. 243.

- ↑ Lukic & Lynch 1996, p. 206.

- ↑ Ramet 2010, p. 263.

- 1 2 3 4 Tanner 2001, p. 286.

- ↑ Ramet 2010, p. 264.

- ↑ "Plans for a 'Greater Croatia' (document)". Bosnian Report. 1 (Bosnian Institute). November–December 1997.

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 348

- 1 2 Ramet 2010, p. 265.

- ↑ Delic judgement 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Tanner 2001, p. 285.

- ↑ "ICTY: Naletilić and Martinović verdict - A. Historical background" (PDF).

- ↑ Hoare 2010, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Hoare 2010, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Ramet 2006, p. 436.

- ↑ Hoare March 1997, p. 127.

- 1 2 Ramet 2006, p. 343.

- ↑ Hockenos 2003, p. 92.

- ↑ Christia 2012, p. 183.

- 1 2 "ICTY: Blaškić verdict - A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993t" (PDF). p. 109.

- 1 2 Ramet (2006), p. 436

- 1 2 3 Toal & Dahlman 2011, p. 105.

- 1 2 Burns 6 July 1992.

- ↑ Williams 9 May 1992.

- ↑ Lukic & Lynch 1996, pp. 210–212.

- ↑ Prlic et al. judgement 2013, p. 155.

- ↑ CIA 2002b, pp. 358.

- ↑ Burg & Shoup 1999, p. 227.

- 1 2 3 Burns 26 July 1992.

- ↑ Nizich 1992, p. 31.

- ↑ Udovički & Štitkovac 2000, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 Tanner 2001, p. 287.

- ↑ Toal & Dahlman 2011, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Trifunovska 1994, p. 656.

- ↑ Burns 21 July 1992.

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 463.

- ↑ Lukic & Lynch 1996, p. 212.

- ↑ Lukic & Lynch 1996, pp. 215.

- ↑ Hoare 2004, p. 86.

- ↑ Zürcher 2003, p. 51.

- 1 2 Burns 22 October 1992.

- ↑ Glenny 1996, p. 196.

- ↑ Goldstein 1999, p. 245.

- ↑ Cviko 25 May 2015.

- ↑ Sudetic 7 September 1992.

- ↑ Sudetic 8 September 1992.

- ↑ Udovički & Štitkovac 2000, p. 192.

- 1 2 Sells 1998, p. 96.

- ↑ Magaš January–July 2007.

- ↑ Šoštarić & Cvitić 30 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoare 2010, p. 128.

- ↑ Zovak 2009, p. 516.

- ↑ Zovak 2009, p. 675.

- ↑ Burns 11 October 1992.

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 146.

- ↑ CIA 2002b, pp. 315-317.

- ↑ CIA 2002b, pp. 317.

- 1 2 3 4 International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. "Case Information Sheet - Hadžihasanović and Kubura" (PDF). Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mazowiecki, Tadeusz (17 November 1993). "Fifth periodic report on the situation of human rights in the territory of the former Yugoslavia". United Nations - Commission on Human Rights.

- ↑ Marijan 2006, pp. 388–389.

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 147.

- ↑ Shrader 2003, p. 69.

- 1 2 CIA 2002, p. 159.

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 148.

- ↑ Burns 27 October 1992.

- ↑ Marijan 2006, p. 398.

- ↑ Prlić et al., Judgement - Volume 2 of 6, p.12

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 170

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 161

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 148

- ↑ "ICTY: Prlić et al. (IT-04-74)" (PDF).

- 1 2 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict - IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - 2. The Conflict in Gornji Vakuf" (PDF).

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 188

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 179

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, pp. 179–180

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: Poziv na predaju".

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: Ko je počeo rat u Gornjem Vakufu".

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: "James Dean" u Gornjem Vakufu".

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, pp. 183–184

- ↑ Designed by asker (2004). "The ABiH Main Attack - Vitez, April, 1993". pub. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ↑ "A PROFESSIONAL KIDNAPPING". sense-agency. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-17. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Judgement and Sentence - IT-95-16: 2. The Case for the Defence". sim.law.uu.nl. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

Kidnapping of Zivko Totic and the Killing of his Bodyguards. In addition to the events in Dusina, Lasva and Busovaca which occurred around January 1993, the kidnapping of Zivko Totic and the killing of his escort on 15 April 1993 is said to have had a seriously destabilising effect on Muslim-Croat relations. Zivko Totic was the head of the HVO Military Police in Zenica. [42] Four or five of Totic's bodyguards were killed during his kidnapping, allegedly by Muslim forces. [43] Zivko Totic himself was not killed, however, and was eventually released. [44]

External link in|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Judgement and Sentence - IT-95-16:(c) Findings of the Trial Chamber". sim.law.uu.nl. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

(c) Findings of the Trial Chamber: Moreover, the "Operations Report" dated 16 April 1993, produced by Zvonimir Cilic, appears to be one-sided in that it only mentions attacks on "Croatian houses in Krcevine and Nadioci", and nothing about the assault on Ahmici and massacres of Muslim civilians. The Report complains of Muslim forces attacking from Preocica and states, inter alia, that "attacks by Muslim forces are becoming more ferocious and bestial". The Trial Chamber finds that this evidence is not conclusive in as much as it could prove either that the Muslims were preparing for an attack or that the Croat forces were creating misinformation and propaganda to prepare their own population for an attack on the Muslims. The correct interpretation depends on the true situation: whether the Muslims were indeed preparing for an attack or not.

External link in|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Transcript - IT-95-14". ICTY. 17 November 1998. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

Q. So you're also not aware that the reason that Zivko Totic was kidnapped was as a bargaining chip to ensure that these Muslims in Kaonik were released by the HVO?

A. I know that Zivko Totic was kidnapped, and I'm not aware that he was kidnapped for those reasons.

Q. In May 1993, are you aware of an exchange that took place in Zenica where Zivko Totic was, in fact, exchanged by Mujahedin for these 13 Muslims that were detained in the Kaonik prison?

A. I'm not aware of that. May 1993, I think that I was already detained in a camp then.

Q. So you are not aware of the reasons why Zivko Totic was kidnapped, are you?

A. No, I'm not aware of that. - 1 2 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict - IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - C. The April 1993 Conflagration in Vitez and the Lašva Valley - 3. The Attack on Ahmići (Paragraph 642)".

- ↑ "Haski procesi" [Trials at the Hague]. News archive (in Croatian) (Croatian Radiotelevision). 29 October 1998.

- ↑ "ICTY (1995): Initial indictment for the ethnic cleansing of the Lasva Valley area - Part II".

- ↑ "ICTY: Summary of sentencing judgement for Miroslav Bralo".

- ↑ CIA 2002b, pp. 417.

- ↑ "Time for Truth: Review of the Work of the War Crimes Chamber of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2005-2010" (PDF). Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. 2010.

- 1 2 3 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict" (PDF).

- ↑ "IDC: Victim statistics in Novi Travnik, Vitez, Kiseljak and Busovača".

- ↑ "ICTY: Blaškić verdict" (PDF).

- ↑ ICTY (Naletilic-Matinovic): 1. Sovici and Doljani- the attack on 17 April 1993 and the following days

- 1 2 3 4 "ICTY: Prlić et al. (IT-04-74)" (PDF).

- ↑ "ICTY: Naletilić and Martinović verdict - Mostar attack" (PDF).

- ↑ "Memic et al: Witnessing the Shooting of Captives". Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Bosnian woman pleads guilty to war crimes". The Montreal Gazette. 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "Witness Admits to Trusina Killings". Balkan insight. 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Kordic and Cerkez verdict - IV. ATTACKS ON TOWNS AND VILLAGES: KILLINGS - D. The June and October Offensives -

- 1 2 Kordic and Cerkez verdict - IV. ATTACKS ON TOWNS AND VILLAGES: KILLINGS - D. The June and October Offensives - 1. The Convoy of Joy -

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 245

- 1 2 Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 246

- ↑ Kordić and Čerkez judgement, p. 248

- ↑ Chuck Sudetich (30 June 1993). "10 Leaders in Bosnia Try To Heal Rift Over Talks.". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ Lawson, Edward (1996). Encyclopedia of Human Rights (Second ed.). Washington D.C.: Taylor & Francis. p. 149.

- ↑ ICTY: Summary of the judgement for Enver Hadžihasanović and Amir Kubura -

- ↑ Bosnia Revokes Citizenship Of 100s of Its Jihadists, balkanpeace.org; accessed 23 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Srebrenica - a 'safe' area". Netherlands Institute for War Documentation. 10 April 2002. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ Karli, Sina (11 November 2006). "Šveđanin priznao krivnju za ratne zločine u BiH" [Swede confesses to war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina]. Nacional (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ CIA 2002, pp. 202.

- ↑ "Kill All Croats in the Village".

- 1 2 "Trojici za Grabovicu 39 godina zatvora".

- ↑ CIA 2002, pp. 203.

- ↑ "Judgement in the Case the Prosecutor v. Sefer Halilovic".

- ↑ ICTY: Prlic et al.

- ↑ The Hague Justice Portal:Hadžihasanović, Enver

- ↑ The Hague Justice Portal:Kubura, Amir

- ↑ Sefer Halilović - Judgement

- ↑ Del Ponte, Carla (2002-01-11), The Prosecutor of the Tribunal Against Enver Hadžihasanović, Mehmed Alagic, Amir Kubura : Amended Indictment, archived from the original on 2005-11-13, retrieved 2008-11-30

- ↑ "Josipovic apologizes for Croatia's role in war in Bosnia". Croatian Times. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ RDC - Research results (2007) - Human Losses in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1991–1995

References

- Books and journals

- Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (1999). The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3189-3.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Christia, Fotini (2012). Alliance Formation in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13985-175-6.

- Glenny, Misha (1996). The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-025771-7.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-525-1.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (March 1997). "The Croatian Project to Partition Bosnia-Hercegovina, 1990-1994". East European Quarterly 31 (1): 121–138.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2004). How Bosnia Armed. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-86356-367-6.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Hockenos, Paul (2003). Homeland Calling: Exile Patriotism and the Balkan Wars. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4158-5.

- Lukic, Reneo; Lynch, Allen (1996). Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829200-5.

- Magaš, Branka (January–July 2007). "Gojko Šušak's Gift to RS". Bosnia Report (Bosnian Institute) (55-56).

- Marijan, Davor (December 2006). "Sukob HVO-a i ABIH u Prozoru, u listopadu 1992." [Clash of the HVO and the ARBiH in Prozor, in October 1992]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian) (Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History) 38 (2): 379–402. ISSN 0590-9597.

- Nizich, Ivana (1992). War Crimes in Bosnia-Heczegovina 1. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-083-4.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). "Politics in Croatia since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P. Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 258–285. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Sells, Michael Anthony (1998). The Bridge Betrayed: Religion and Genocide in Bosnia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92209-9.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09125-0.

- Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973036-0.

- Trifunovska, Snežana (1994). Yugoslavia Through Documents: From its Creation to its Dissolution. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7923-2670-0.

- Udovički, Jasminka; Štitkovac, Ejub (2000). "Bosnia and Hercegovina: The Second War". In Udovički, Jasminka; Ridgeway, James. Burn This House: The Making and Unmaking of Yugoslavia. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 175–216. ISBN 978-0-8223-2590-1.

- Zovak, Jerko (2009). Rat u Bosanskoj Posavini 1992. [War in Bosnian Sava Basin 1992] (in Croatian). Slavonski Brod, Croatia: Posavska Hrvatska. ISBN 978-953-6357-86-4.

- Zürcher, Christoph (2003). Potentials of Disorder: Explaining Conflict and Stability in the Caucasus and in the Former Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6241-4.

- News articles

- Burns, John F. (6 July 1992). "Croats Claim Their Own Slice of Bosnia". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (21 July 1992). "U.N. Resumes Relief Flights to Sarajevo". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (26 July 1992). "Croatian Pact Holds Risks for Bosnians". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (11 October 1992). "Bosnia Loss Hints at Croat-Serb Deal". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (22 October 1992). "Serbs and Croats Now Join In Devouring Bosnia's Land". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (27 October 1992). "Attacks by Croatian Force Put New Strains on Bosnian Government's Unity". New York Times.

- Cviko, M. (25 May 2015). "Manolić otkrio istinu Blaž Kraljević ubijen je po naredbi Gojka Šuška i uz blagoslov Franje Tuđmana!" [Manolić revealed the truth that Blaž Kraljević was killed on the orders of Gojko Šušak and with the blessing of Franjo Tuđman!] (in Serbo-Croatian). Dnevni Avaz.

- Šoštarić, Eduard; Cvitić, Plamenko (30 January 2007). "Susak Handed Over the Posavina Region". Nacional.

- Sudetic, Chuck (7 September 1992). "Croatians Insist Muslim Fighters Leave Sarajevo Buffer Area". New York Times.

- Sudetic, Chuck (8 September 1992). "Croatian Militia Denies Issuing a Broad Challenge to Bosnia". New York Times.

- Williams, Carol J. (9 May 1992). "Serbs, Croats Met Secretly to Split Bosnia". Los Angeles Times.

- International, governmental, and NGO sources

- "Prlić et al. – Case Information Sheet" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. IT-04-74.

- "Prosecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2001.

- "Prosecutor v. Rasim Delić Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 September 2008.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić - Judgement - Volume 1 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||