Borel measure

In mathematics, specifically in measure theory, a Borel measure on a topological space is a measure that is defined on all open sets (and thus on all Borel sets).[1] Some authors require additional restrictions on the measure, as described below.

Formal definition

Let X be a locally compact Hausdorff space, and let  be the smallest σ-algebra that contains the open sets of X; this is known as the σ-algebra of Borel sets. A Borel measure is any measure μ defined on the σ-algebra of Borel sets.[2] Some authors require in addition that μ(C) < ∞ for every compact set C. If a Borel measure μ is both inner regular and outer regular, it is called a regular Borel measure (some authors also require it to be tight). If μ is both inner regular and locally finite, it is called a Radon measure. Note that a locally finite Borel measure automatically satisfies μ(C) < ∞ for every compact set C.

be the smallest σ-algebra that contains the open sets of X; this is known as the σ-algebra of Borel sets. A Borel measure is any measure μ defined on the σ-algebra of Borel sets.[2] Some authors require in addition that μ(C) < ∞ for every compact set C. If a Borel measure μ is both inner regular and outer regular, it is called a regular Borel measure (some authors also require it to be tight). If μ is both inner regular and locally finite, it is called a Radon measure. Note that a locally finite Borel measure automatically satisfies μ(C) < ∞ for every compact set C.

On the real line

The real line  with its usual topology is a locally compact Hausdorff space, hence we can define a Borel measure on it. In this case,

with its usual topology is a locally compact Hausdorff space, hence we can define a Borel measure on it. In this case,  is the smallest σ-algebra that contains the open intervals of

is the smallest σ-algebra that contains the open intervals of  . While there are many Borel measures μ, the choice of Borel measure which assigns

. While there are many Borel measures μ, the choice of Borel measure which assigns ![\mu([a,b])=b-a](../I/m/bf767e1e60b0c828f12be60d726c6e86.png) for every interval

for every interval ![[a,b]](../I/m/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) is sometimes called "the" Borel measure on

is sometimes called "the" Borel measure on  . In practice, even "the" Borel measure is not the most useful measure defined on the σ-algebra of Borel sets; indeed, the Lebesgue measure

. In practice, even "the" Borel measure is not the most useful measure defined on the σ-algebra of Borel sets; indeed, the Lebesgue measure  is an extension of "the" Borel measure which possesses the crucial property that it is a complete measure (unlike the Borel measure). To clarify, when one says that the Lebesgue measure

is an extension of "the" Borel measure which possesses the crucial property that it is a complete measure (unlike the Borel measure). To clarify, when one says that the Lebesgue measure  is an extension of the Borel measure

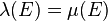

is an extension of the Borel measure  , it means that every Borel-measurable set E is also a Lebesgue-measurable set, and the Borel measure and the Lebesgue measure coincide on the Borel sets (i.e.,

, it means that every Borel-measurable set E is also a Lebesgue-measurable set, and the Borel measure and the Lebesgue measure coincide on the Borel sets (i.e.,  for every Borel measurable set).

for every Borel measurable set).

Product spaces

If X and Y are second-countable, Hausdorff topological spaces, then the set of Borel subsets  of their product coincides with the product of the sets

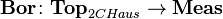

of their product coincides with the product of the sets  of Borel subsets of X and Y.[3] That is, the Borel functor

of Borel subsets of X and Y.[3] That is, the Borel functor

from the category of second-countable Hausdorff spaces to the category of measurable spaces preserves finite products.

Applications

Lebesgue–Stieltjes integral

The Lebesgue–Stieltjes integral is the ordinary Lebesgue integral with respect to a measure known as the Lebesgue–Stieltjes measure, which may be associated to any function of bounded variation on the real line. The Lebesgue–Stieltjes measure is a regular Borel measure, and conversely every regular Borel measure on the real line is of this kind.[4]

Laplace transform

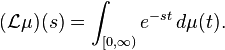

One can define the Laplace transform of a finite Borel measure μ on the real line by the Lebesgue integral[5]

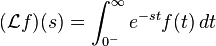

An important special case is where μ is a probability measure or, even more specifically, the Dirac delta function. In operational calculus, the Laplace transform of a measure is often treated as though the measure came from a distribution function f. In that case, to avoid potential confusion, one often writes

where the lower limit of 0− is shorthand notation for

This limit emphasizes that any point mass located at 0 is entirely captured by the Laplace transform. Although with the Lebesgue integral, it is not necessary to take such a limit, it does appear more naturally in connection with the Laplace–Stieltjes transform.

Hausdorff dimension and Frostman's lemma

Given a Borel measure μ on a metric space X such that μ(X) > 0 and μ(B(x, r)) ≤ rs holds for some constant s > 0 and for every ball B(x, r) in X, then the Hausdorff dimension dimHaus(X) ≥ s. A partial converse is provided by Frostman's lemma:[6]

Lemma: Let A be a Borel subset of Rn, and let s > 0. Then the following are equivalent:

- Hs(A) > 0, where Hs denotes the s-dimensional Hausdorff measure.

- There is an (unsigned) Borel measure μ satisfying μ(A) > 0, and such that

- holds for all x ∈ Rn and r > 0.

Cramér–Wold theorem

The Cramér–Wold theorem in measure theory states that a Borel probability measure on  is uniquely determined by the totality of its one-dimensional projections.[7] It is used as a method for proving joint convergence results. The theorem is named after Harald Cramér and Herman Ole Andreas Wold.

is uniquely determined by the totality of its one-dimensional projections.[7] It is used as a method for proving joint convergence results. The theorem is named after Harald Cramér and Herman Ole Andreas Wold.

References

- ↑ D. H. Fremlin, 2000. Measure Theory. Torres Fremlin.

- ↑ Alan J. Weir (1974). General integration and measure. Cambridge University Press. pp. 158–184. ISBN 0-521-29715-X.

- ↑ Vladimir I. Bogachev. Measure Theory, Volume 1. Springer Science & Business Media, Jan 15, 2007

- ↑ Halmos, Paul R. (1974), Measure Theory, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90088-9

- ↑ Feller 1971, §XIII.1

- ↑ Rogers, C. A. (1998). Hausdorff measures. Cambridge Mathematical Library (Third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxx+195. ISBN 0-521-62491-6.

- ↑ K. Stromberg, 1994. Probability Theory for Analysts. Chapman and Hall.

Further reading

- Feller, William (1971), An introduction to probability theory and its applications. Vol. II., Second edition, New York: John Wiley & Sons, MR 0270403.

- J. D. Pryce (1973). Basic methods of functional analysis. Hutchinson University Library. Hutchinson. p. 217. ISBN 0-09-113411-0.

- Ransford, Thomas (1995). Potential theory in the complex plane. London Mathematical Society Student Texts 28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 209–218. ISBN 0-521-46654-7. Zbl 0828.31001.

- Teschl, Gerald, Topics in Real and Functional Analysis, (lecture notes)