Bootstrapping (statistics)

In statistics, bootstrapping can refer to any test or metric that relies on random sampling with replacement. Bootstrapping allows assigning measures of accuracy (defined in terms of bias, variance, confidence intervals, prediction error or some other such measure) to sample estimates.[1][2] This technique allows estimation of the sampling distribution of almost any statistic using random sampling methods.[3][4] Generally, it falls in the broader class of resampling methods.

Bootstrapping is the practice of estimating properties of an estimator (such as its variance) by measuring those properties when sampling from an approximating distribution. One standard choice for an approximating distribution is the empirical distribution function of the observed data. In the case where a set of observations can be assumed to be from an independent and identically distributed population, this can be implemented by constructing a number of resamples with replacement, of the observed dataset (and of equal size to the observed dataset).

It may also be used for constructing hypothesis tests. It is often used as an alternative to statistical inference based on the assumption of a parametric model when that assumption is in doubt, or where parametric inference is impossible or requires complicated formulas for the calculation of standard errors.

History

The bootstrap was published by Bradley Efron in "Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife" (1979).[5][6][7] It was inspired by earlier work on the jackknife.[8][9][10] Improved estimates of the variance were developed later.[11][12] A Bayesian extension was developed in 1981.[13] The bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap was developed by Efron in 1987,[14] and the ABC procedure in 1992.[15]

Approach

The basic idea of bootstrapping is that inference about a population from sample data (sample → population) can be modeled by resampling the sample data and performing inference on (resample → sample). As the population is unknown, the true error in a sample statistic against its population value is unknowable. In bootstrap-resamples, the 'population' is in fact the sample, and this is known; hence the quality of inference from resample data → 'true' sample is measurable.

More formally, the bootstrap works by treating inference of the true probability distribution J, given the original data, as being analogous to inference of the empirical distribution of Ĵ, given the resampled data. The accuracy of inferences regarding Ĵ using the resampled data can be assessed because we know Ĵ. If Ĵ is a reasonable approximation to J, then the quality of inference on J can in turn be inferred.

As an example, assume we are interested in the average (or mean) height of people worldwide. We cannot measure all the people in the global population, so instead we sample only a tiny part of it, and measure that. Assume the sample is of size N; that is, we measure the heights of N individuals. From that single sample, only one estimate of the mean can be obtained. In order to reason about the population, we need some sense of the variability of the mean that we have computed.

The simplest bootstrap method involves taking the original data set of N heights, and, using a computer, sampling from it to form a new sample (called a 'resample' or bootstrap sample) that is also of size N. The bootstrap sample is taken from the original using sampling with replacement so, assuming N is sufficiently large, for all practical purposes there is virtually zero probability that it will be identical to the original "real" sample. This process is repeated a large number of times (typically 1,000 or 10,000 times), and for each of these bootstrap samples we compute its mean (each of these are called bootstrap estimates). We now have a histogram of bootstrap means. This provides an estimate of the shape of the distribution of the mean from which we can answer questions about how much the mean varies. (The method here, described for the mean, can be applied to almost any other statistic or estimator.)

Situations where bootstrapping is useful, and limitations

Adèr et al. recommend the bootstrap procedure for the following situations:[16]

- When the theoretical distribution of a statistic of interest is complicated or unknown. Since the bootstrapping procedure is distribution-independent it provides an indirect method to assess the properties of the distribution underlying the sample and the parameters of interest that are derived from this distribution.

- When the sample size is insufficient for straightforward statistical inference. If the underlying distribution is well-known, bootstrapping provides a way to account for the distortions caused by the specific sample that may not be fully representative of the population.

- When power calculations have to be performed, and a small pilot sample is available. Most power and sample size calculations are heavily dependent on the standard deviation of the statistic of interest. If the estimate used is incorrect, the required sample size will also be wrong. One method to get an impression of the variation of the statistic is to use a small pilot sample and perform bootstrapping on it to get impression of the variance.

However, Athreya has shown[17] that if one performs a naive bootstrap on the sample mean when the underlying population lacks a finite variance (for example, a power law distribution), then the bootstrap distribution will not converge to the same limit as the sample mean. As a result, confidence intervals on the basis of a Monte Carlo simulation of the bootstrap could be misleading. Athreya states that "Unless one is reasonably sure that the underlying distribution is not heavy tailed, one should hesitate to use the naive bootstrap".

Discussion

Advantages

A great advantage of bootstrap is its simplicity. It is a straightforward way to derive estimates of standard errors and confidence intervals for complex estimators of complex parameters of the distribution, such as percentile points, proportions, odds ratio, and correlation coefficients. Bootstrap is also an appropriate way to control and check the stability of the results. Although for most problems it is impossible to know the true confidence interval, bootstrap is asymptotically more accurate than the standard intervals obtained using sample variance and assumptions of normality.[18]

Disadvantages

Although bootstrapping is (under some conditions) asymptotically consistent, it does not provide general finite-sample guarantees. The apparent simplicity may conceal the fact that important assumptions are being made when undertaking the bootstrap analysis (e.g. independence of samples) where these would be more formally stated in other approaches.

Recommendations

The number of bootstrap samples recommended in literature has increased as available computing power has increased. If the results may have substantial real-world consequences, then one should use as many samples as is reasonable, given available computing power and time. Increasing the number of samples cannot increase the amount of information in the original data; it can only reduce the effects of random sampling errors which can arise from a bootstrap procedure itself.

Types of bootstrap scheme

In univariate problems, it is usually acceptable to resample the individual observations with replacement ("case resampling" below). In small samples, a parametric bootstrap approach might be preferred. For other problems, a smooth bootstrap will likely be preferred.

For regression problems, various other alternatives are available.[19]

Case resampling

Bootstrap is generally useful for estimating the distribution of a statistic (e.g. mean, variance) without using normal theory (e.g. z-statistic, t-statistic). Bootstrap comes in handy when there is no analytical form or normal theory to help estimate the distribution of the statistics of interest, since bootstrap method can apply to most random quantities, e.g., the ratio of variance and mean. There are at least two ways of performing case resampling.

- The Monte Carlo algorithm for case resampling is quite simple. First, we resample the data with replacement, and the size of the resample must be equal to the size of the original data set. Then the statistic of interest is computed from the resample from the first step. We repeat this routine many times to get a more precise estimate of the Bootstrap distribution of the statistic.

- The 'exact' version for case resampling is similar, but we exhaustively enumerate every possible resample of the data set. This can be computationally expensive as there are a total of

different resamples, where n is the size of the data set.

different resamples, where n is the size of the data set.

Estimating the distribution of sample mean

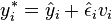

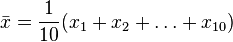

Consider a coin-flipping experiment. We flip the coin and record whether it lands heads or tails. Let X = x1, x2, …, x10 be 10 observations from the experiment. xi = 1 if the i th flip lands heads, and 0 otherwise. From normal theory, we can use t-statistic to estimate the distribution of the sample mean,  .

.

Instead, we use bootstrap, specifically case resampling, to derive the distribution of  . We first resample the data to obtain a bootstrap resample. An example of the first resample might look like this X1* = x2, x1, x10, x10, x3, x4, x6, x7, x1, x9. Note that there are some duplicates since a bootstrap resample comes from sampling with replacement from the data. Note also that the number of data points in a bootstrap resample is equal to the number of data points in our original observations. Then we compute the mean of this resample and obtain the first bootstrap mean: μ1*. We repeat this process to obtain the second resample X2* and compute the second bootstrap mean μ2*. If we repeat this 100 times, then we have μ1*, μ2*, …, μ100*. This represents an empirical bootstrap distribution of sample mean. From this empirical distribution, one can derive a bootstrap confidence interval for the purpose of hypothesis testing.

. We first resample the data to obtain a bootstrap resample. An example of the first resample might look like this X1* = x2, x1, x10, x10, x3, x4, x6, x7, x1, x9. Note that there are some duplicates since a bootstrap resample comes from sampling with replacement from the data. Note also that the number of data points in a bootstrap resample is equal to the number of data points in our original observations. Then we compute the mean of this resample and obtain the first bootstrap mean: μ1*. We repeat this process to obtain the second resample X2* and compute the second bootstrap mean μ2*. If we repeat this 100 times, then we have μ1*, μ2*, …, μ100*. This represents an empirical bootstrap distribution of sample mean. From this empirical distribution, one can derive a bootstrap confidence interval for the purpose of hypothesis testing.

Regression

In regression problems, case resampling refers to the simple scheme of resampling individual cases - often rows of a data set. For regression problems, so long as the data set is fairly large, this simple scheme is often acceptable. However, the method is open to criticism.

In regression problems, the explanatory variables are often fixed, or at least observed with more control than the response variable. Also, the range of the explanatory variables defines the information available from them. Therefore, to resample cases means that each bootstrap sample will lose some information. As such, alternative bootstrap procedures should be considered.

Bayesian bootstrap

Bootstrapping can be interpreted in a Bayesian framework using a scheme that creates new datasets through reweighting the initial data. Given a set of  data points, the weighting assigned to data point

data points, the weighting assigned to data point  in a new dataset

in a new dataset  is

is  , where

, where  is a low-to-high ordered list of

is a low-to-high ordered list of  uniformly distributed random numbers on

uniformly distributed random numbers on ![[0,1]](../I/m/ccfcd347d0bf65dc77afe01a3306a96b.png) , preceded by 0 and succeeded by 1. The distributions of a parameter inferred from considering many such datasets

, preceded by 0 and succeeded by 1. The distributions of a parameter inferred from considering many such datasets  are then interpretable as posterior distributions on that parameter.[20]

are then interpretable as posterior distributions on that parameter.[20]

Smooth bootstrap

Under this scheme, a small amount of (usually normally distributed) zero-centered random noise is added onto each resampled observation. This is equivalent to sampling from a kernel density estimate of the data.

Parametric bootstrap

In this case a parametric model is fitted to the data, often by maximum likelihood, and samples of random numbers are drawn from this fitted model. Usually the sample drawn has the same sample size as the original data. Then the quantity, or estimate, of interest is calculated from these data. This sampling process is repeated many times as for other bootstrap methods. The use of a parametric model at the sampling stage of the bootstrap methodology leads to procedures which are different from those obtained by applying basic statistical theory to inference for the same model.

Resampling residuals

Another approach to bootstrapping in regression problems is to resample residuals. The method proceeds as follows.

- Fit the model and retain the fitted values

and the residuals

and the residuals  .

. - For each pair, (xi, yi), in which xi is the (possibly multivariate) explanatory variable, add a randomly resampled residual,

, to the response variable yi. In other words, create synthetic response variables

, to the response variable yi. In other words, create synthetic response variables  where j is selected randomly from the list (1, …, n) for every i.

where j is selected randomly from the list (1, …, n) for every i. - Refit the model using the fictitious response variables

, and retain the quantities of interest (often the parameters,

, and retain the quantities of interest (often the parameters,  , estimated from the synthetic

, estimated from the synthetic  ).

). - Repeat steps 2 and 3 a large number of times.

This scheme has the advantage that it retains the information in the explanatory variables. However, a question arises as to which residuals to resample. Raw residuals are one option; another is studentized residuals (in linear regression). Whilst there are arguments in favour of using studentized residuals; in practice, it often makes little difference and it is easy to run both schemes and compare the results against each other.

Gaussian process regression bootstrap

When data are temporally correlated, straightforward bootstrapping destroys the inherent correlations. This method uses Gaussian process regression to fit a probabilistic model from which replicates may then be drawn. Gaussian processes are methods from Bayesian non-parametric statistics but are here used to construct a parametric bootstrap approach, which implicitly allows the time-dependence of the data to be taken into account.

Wild bootstrap

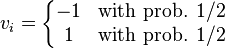

The Wild bootstrap, proposed originally by Wu (1986),[21] is suited when the model exhibits heteroskedasticity. The idea is, like the residual bootstrap, to leave the regressors at their sample value, but to resample the response variable based on the residuals values. That is, for each replicate, one computes a new  based on

based on

so the residuals are randomly multiplied by a random variable  with mean 0 and variance 1. This method assumes that the 'true' residual distribution is symmetric and can offer advantages over simple residual sampling for smaller sample sizes. Different forms are used for the random variable

with mean 0 and variance 1. This method assumes that the 'true' residual distribution is symmetric and can offer advantages over simple residual sampling for smaller sample sizes. Different forms are used for the random variable  , such as

, such as

- A distribution suggested by Mammen (1993).[22]

- Or the simpler distribution, linked to the Rademacher distribution:

Block bootstrap

The block bootstrap is used when the data, or the errors in a model, are correlated. In this case, a simple case or residual resampling will fail, as it is not able to replicate the correlation in the data. The block bootstrap tries to replicate the correlation by resampling instead blocks of data. The block bootstrap has been used mainly with data correlated in time (i.e. time series) but can also be used with data correlated in space, or among groups (so-called cluster data).

Time series: Simple block bootstrap

In the (simple) block bootstrap, the variable of interest is split into non-overlapping blocks.

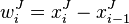

Time series: Moving block bootstrap

In the moving block bootstrap, introduced by Künsch (1989),[23] data is split into n-b+1 overlapping blocks of length b: Observation 1 to b will be block 1, observation 2 to b+1 will be block 2 etc. Then from these n-b+1 blocks, n/b blocks will be drawn at random with replacement. Then aligning these n/b blocks in the order they were picked, will give the bootstrap observations.

This bootstrap works with dependent data, however, the bootstrapped observations will not be stationary anymore by construction. But, it was shown that varying randomly the block length can avoid this problem.[24] This method is known as the stationary bootstrap. Other related modifications of the moving block bootstrap are the Markovian bootstrap and a stationary bootstrap method that matches subsequent blocks based on standard deviation matching.

Cluster data: block bootstrap

Cluster data describes data where many observations per unit are observed. This could be observing many firms in many states, or observing students in many classes. In such cases, the correlation structure is simplified, and one does usually make the assumption that data is correlated with a group/cluster, but independent between groups/clusters. The structure of the block bootstrap is easily obtained (where the block just corresponds to the group), and usually only the groups are resampled, while the observations within the groups are left unchanged. Cameron et al. (2008) [25] discusses this for clustered errors in linear regression.

Choice of statistic

The bootstrap distribution of a point estimator of a population parameter has been used to produce a bootstrapped confidence interval for the parameter's true value, if the parameter can be written as a function of the population's distribution.

Population parameters are estimated with many point estimators. Popular families of point-estimators include mean-unbiased minimum-variance estimators, median-unbiased estimators, Bayesian estimators (for example, the posterior distribution's mode, median, mean), and maximum-likelihood estimators.

A Bayesian point estimator and a maximum-likelihood estimator have good performance when the sample size is infinite, according to asymptotic theory. For practical problems with finite samples, other estimators may be preferable. Asymptotic theory suggests techniques that often improve the performance of bootstrapped estimators; the bootstrapping of a maximum-likelihood estimator may often be improved using transformations related to pivotal quantities.[26]

Deriving confidence intervals from the bootstrap distribution

The bootstrap distribution of a parameter-estimator has been used to calculate confidence intervals for its population-parameter.

Bias, asymmetry, and confidence intervals

- Bias: The bootstrap distribution and the sample may disagree systematically, in which case bias may occur.

- If the bootstrap distribution of an estimator is symmetric, then percentile confidence-interval are often used; such intervals are appropriate especially for median-unbiased estimators of minimum risk (with respect to an absolute loss function). Bias in the bootstrap distribution will lead to bias in the confidence-interval.

- Otherwise, if the bootstrap distribution is non-symmetric, then percentile confidence-intervals are often inappropriate.

Methods for bootstrap confidence intervals

There are several methods for constructing confidence intervals from the bootstrap distribution of a real parameter:

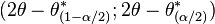

- Basic Bootstrap. The basic bootstrap is the simplest scheme to construct the confidence interval: one simply takes the empirical quantiles from the bootstrap distribution of the parameter (see Davison and Hinkley 1997, equ. 5.6 p. 194):

where

where  denotes the

denotes the  percentile of the bootstrapped coefficients

percentile of the bootstrapped coefficients  .

.

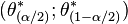

- Percentile Bootstrap. The percentile bootstrap proceeds in a similar way to the basic bootstrap, using percentiles of the bootstrap distribution, but with a different formula (note the inversion of the left and right quantiles!):

where

where  denotes the

denotes the  percentile of the bootstrapped coefficients

percentile of the bootstrapped coefficients  .

.

See Davison and Hinkley (1997, equ. 5.18 p. 203) and Efron and Tibshirani (1993, equ 13.5 p. 171). This method can be applied to any statistic. It will work well in cases where the bootstrap distribution is symmetrical and centered on the observed statistic[27] and where the sample statistic is median-unbiased and has maximum concentration (or minimum risk with respect to an absolute value loss function). In other cases, the percentile bootstrap can be too narrow. When working with small sample sizes (i.e., less than 50), the percentile confidence intervals for (for example) the variance statistic will be too narrow. So that with a sample of 20 points, 90% confidence interval will include the true variance only 78% of the time[28]

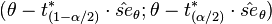

- Studentized Bootstrap. The studentized bootstrap, also called bootstrap-t, works similarly as the usual confidence interval, but replaces the quantiles from the normal or student approximation by the quantiles from the bootstrap distribution of the Student's t-test (see Davison and Hinkley 1997, equ. 5.7 p. 194 and Efron and Tibshirani 1993 equ 12.22, p. 160):

where

where  denotes the

denotes the  percentile of the bootstrapped Student's t-test

percentile of the bootstrapped Student's t-test  , while

, while  is the estimated standard error of the coefficient in the original model.

is the estimated standard error of the coefficient in the original model.

The studentized test enjoys optimal properties as the statistic that is bootstrapped is pivotal (i.e. it does not depend on nuisance parameters as the t-test follows asymptotically a N(0,1) distribution), unlike the percentile bootstrap.

- Bias-Corrected Bootstrap - adjusts for bias in the bootstrap distribution.

- Accelerated Bootstrap - The bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap, by Efron (1987),[14] adjusts for both bias and skewness in the bootstrap distribution. This approach is accurate in a wide variety of settings, has reasonable computation requirements, and produces reasonably narrow intervals.

Example applications

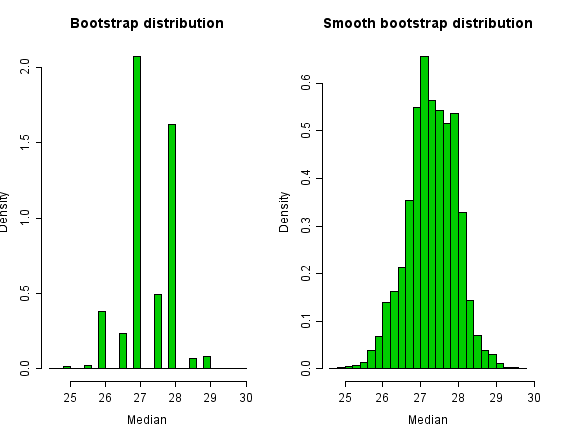

Smoothed bootstrap

In 1878, Simon Newcomb took observations on the speed of light.[29] The data set contains two outliers, which greatly influence the sample mean. (Note that the sample mean need not be a consistent estimator for any population mean, because no mean need exist for a heavy-tailed distribution.) A well-defined and robust statistic for central tendency is the sample median, which is consistent and median-unbiased for the population median.

The bootstrap distribution for Newcomb's data appears below. A convolution-method of regularization reduces the discreteness of the bootstrap distribution, by adding a small amount of N(0, σ2) random noise to each bootstrap sample. A conventional choice is  for sample size n.

for sample size n.

Histograms of the bootstrap distribution and the smooth bootstrap distribution appear below

. The bootstrap distribution of the sample-median has only a small number of values. The smoothed bootstrap distribution has a richer support.

In this example, the bootstrapped 95% (percentile) confidence-interval for the population median is (26, 28.5), which is close to the interval for (25.98, 28.46) for the smoothed bootstrap.

Relation to other approaches to inference

Relationship to other resampling methods

The bootstrap is distinguished from :

- the jackknife procedure, used to estimate biases of sample statistics and to estimate variances, and

- cross-validation, in which the parameters (e.g., regression weights, factor loadings) that are estimated in one subsample are applied to another subsample.

For more details see bootstrap resampling.

Bootstrap aggregating (bagging) is a meta-algorithm based on averaging the results of multiple bootstrap samples.

U-statistics

In situations where an obvious statistic can be devised to measure a required characteristic using only a small number, r, of data items, a corresponding statistic based on the entire sample can be formulated. Given an r-sample statistic, one can create an n-sample statistic by something similar to bootstrapping (taking the average of the statistic over all subsamples of size r). This procedure is known to have certain good properties and the result is a U-statistic. The sample mean and sample variance are of this form, for r=1 and r=2.

See also

- Accuracy and precision

- Bootstrap aggregating

- Empirical likelihood

- Imputation (statistics)

- Reliability (statistics)

- Reproducibility

References

- ↑ Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R. (1993). An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 0-412-04231-2. software

- ↑ Second Thoughts on the Bootstrap - Bradley Efron, 2003

- ↑ Varian, H.(2005). "Bootstrap Tutorial". Mathematica Journal, 9, 768-775.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Bootstrap Methods." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/BootstrapMethods.html

- ↑ Notes for Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics: Bootstrap (John Aldrich)

- ↑ Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (B) (Jeff Miller)

- ↑ Efron, B. (1979). "Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife". The Annals of Statistics 7 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1214/aos/1176344552.

- ↑ Quenouille M (1949) Approximate tests of correlation in time-series. J Roy Statist Soc Ser B 11 68–84

- ↑ Tukey J (1958) Bias and confidence in not-quite large samples (abstract). Ann Math Statist 29 614

- ↑ Jaeckel L (1972) The infinitesimal jackknife. Memorandum MM72-1215-11, Bell Lab

- ↑ Bickel P, Freeman D (1981) Some asymptotic theory for the bootstrap. Ann Statist 9 1196–1217

- ↑ Singh K (1981) On the asymptotic accuracy of Efron’s bootstrap. Ann Statist 9 1187–1195

- ↑ Rubin D (1981). The Bayesian bootstrap. Ann Statist 9 130–134

- 1 2 Efron, B. (1987). "Better Bootstrap Confidence Intervals". Journal of the American Statistical Association (Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 82, No. 397) 82 (397): 171–185. doi:10.2307/2289144. JSTOR 2289144.

- ↑ Diciccio T, Efron B (1992) More accurate confidence intervals in exponential families. Biometrika 79 231–245

- ↑ Adèr, H. J., Mellenbergh G. J., & Hand, D. J. (2008). Advising on research methods: A consultant's companion. Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing. ISBN 978-90-79418-01-5

- ↑ Bootstrap of the mean in the infinite variance case Athreya, K.B. Ann Stats vol 15 (2) 1987 724-731

- ↑ DiCiccio TJ, Efron B (1996) Bootstrap confidence intervals (with Discussion). Statistical Science 11: 189-228

- ↑ Efron B., R. J. Tibshirani, An introduction to the bootstrap, Chapman & Hall/CRC 1998

- ↑ Rubin, D. B. (1981). "The Bayesian bootstrap". Annals of Statistics, 9, 130.

- ↑ Wu, C.F.J. (1986). "Jackknife, bootstrap and other resampling methods in regression analysis (with discussions)". Annals of Statistics 14: 1261–1350. doi:10.1214/aos/1176350142.

- ↑ Mammen, E. (Mar 1993). "Bootstrap and wild bootstrap for high dimensional linear models". Annals of Statistics 21 (1): 255–285. doi:10.1214/aos/1176349025.

- ↑ Künsch, H. R. (1989). “The jackknife and the bootstrap for general stationary observations,” Annals of Statistics, 17, 1217–1241.

- ↑ Politis, D.N. and Romano, J.P. (1994). The stationary bootstrap. Journal of American Statistical Association, 89, 1303-1313.

- ↑ Cameron, A. C., J. B. Gelbach, and D. L. Miller (2008): “Bootstrap-based im- provements for inference with clustered errors,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 414–427

- ↑ Davison, A. C.; Hinkley, D. V. (1997). Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57391-2. software.

- ↑ Efron, B. (1982). The jackknife, the bootstrap, and other resampling plans 38. Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics CBMS-NSF Monographs. ISBN 0-89871-179-7.

- ↑ Scheiner, S. (1998). Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments. CRC Press. ISBN 0412035618.

- ↑ Data from examples in Bayesian Data Analysis

Further reading

- Diaconis, P. & Efron, B. (May 1983). "Computer-intensive methods in statistics" (PDF). Scientific American: 116–130. popular-science

- Efron, B. (1981). "Nonparametric estimates of standard error: The jackknife, the bootstrap and other methods". Biometrika 68 (3): 589–599. doi:10.1093/biomet/68.3.589.

- Hesterberg, T. C., D. S. Moore, S. Monaghan, A. Clipson, and R. Epstein (2005). "Bootstrap methods and permutation tests". In David S. Moore and George McCabe. Introduction to the Practice of Statistics (pdf). software.

External links

- Bootstrap sampling tutorial using MS Excel

- Bootstrap example to simulate stock prices using MS Excel

- bootstrapping tutorial

- package animation

Software

- Statistics101: Resampling, Bootstrap, Monte Carlo Simulation program. Free program written in Java to run on any operating system.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||