Book of Documents

|

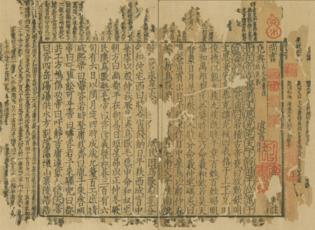

Title page of annotated Shujing edition printed in 1279, held by Taiwan's National Central Library | |

| Author | Various; compilation traditionally attributed to Confucius |

|---|---|

| Original title | 書 Shū |

| Country | Zhou China |

| Language | Old Chinese |

| Subject | Compilation of rhetorical prose |

The Book of Documents (Shujing, earlier Shu-king) or Classic of History, also known as the Shangshu, is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a collection of rhetorical prose attributed to figures of ancient China, and served as the foundation of Chinese political philosophy for over 2,000 years.

The Book of Documents was the subject of one of China's oldest literary controversies, between proponents of different versions of the text. The "New Text" version was preserved from Qin Shi Huang's burning of books and burying of scholars by scholar Fu Sheng. The longer "Old Text" version was supposedly discovered in the wall of Confucius' family estate in Qufu by his descendant Kong Anguo in the late 2nd century BC, lost at the end of the Han dynasty and rediscovered in the 4th century AD. Over time, the "Old Text" version of the Documents became more widely accepted, until it was established as the imperially sanctioned edition during the early Tang dynasty. This continued until the late 17th century, when the Qing dynasty scholar Yan Ruoqu demonstrated that the additional "Old Text" chapters not contained in the "New Text" version were actually fabrications "reconstructed" in the 3rd or 4th centuries AD.

The chapters are grouped into four sections representing different eras: the semi-mythical reign of Yu the Great, and the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. The Zhou section accounts for over half the text. Some of its New Text chapters are among the earliest examples of Chinese prose, recording speeches from the early years of the Zhou dynasty in the late 11th century BC. Although the other three sections purport to record earlier material, most scholars believe that even the New Text chapters in these sections were composed later than those in the Zhou section, with chapters relating to the earliest periods being as recent as the 4th or 3rd centuries BC.

Textual history

The history of the various versions of the Documents is particularly complex, and has been the subject of a long-running literary and philosophical controversy.

Early references

According to a later tradition, the Book of Documents was compiled by Confucius (551–479 BC) as a selection from a much larger group of documents, with some of the remainder being included in the Yizhoushu.[2] However, the early history of both texts is obscure.[3] Beginning with Confucius, writers increasingly drew on the Documents to illustrate general principles, though it seems that several different versions were in use.[4]

Six citations of unnamed Shū (書) appear in the Analects. Although Confucius invoked the pre-dynastic emperors Yao and Shun, and figures from the Xia and Shang dynasties, he complained of the lack of documentation prior to the Zhou. Increasing numbers of citations, some with titles, appear in 4th century BC works such as the Mencius, Mozi and Commentary of Zuo. These authors favoured documents relating to Yao, Shun and the Xia dynasty, chapters now believed to have been written in the Warring States period. The chapters currently believed to be the oldest (mostly relating to the early Zhou) were little used by Warring States authors, perhaps due to the difficulty of the archaic language or a less familiar world-view.[5] Fewer than half the passages quoted by these authors are present in the received text.[6] Authors such as Mencius and Xunzi, while quoting the Documents, refused to accept all of it as genuine. Their attitude contrasts with the reverence that would be shown to the text in the Han dynasty, when its compilation was attributed to Confucius.[7]

Han dynasty: New and Old Texts

Many copies of the work were destroyed in the Burning of Books during the Qin dynasty. Fu Sheng reconstructed part of the work from hidden copies in the late 3rd to early 2nd century BC, at the start of the succeeding Han dynasty. His version was known as the "New Text" (今文 jīn wén lit. "modern script") because it was written in the clerical script.[8][9] It originally consisted of 29 chapters, but the "Great Speech" chapter was lost shortly afterwards and replaced by a new version.[10] The remaining 28 chapters were later expanded to 33 when Du Lin divided some chapters during the 1st century.

Another version was said to have been recovered from a wall of the home of Confucius in 186 BC by his descendent Kong Anguo. This version was known as the "Old Text" (古文 gǔ wén lit. "ancient script"), because it was originally written in the pre-Qin seal script.[9] Han dynasty sources give contradictory accounts of the nature of this find.[11] According to the commonly repeated account of the Book of Han, the Old Text included the chapters preserved by Fu Sheng, another version of the "Great Speech" chapter and some 16 additional chapters.[9] It was part of the Old Text Classics collated by Liu Xiang and championed by his son Liu Xin.[12] A list of 100 chapter titles was also in circulation; many are mentioned in the Records of the Grand Historian, but without quoting the text of the other chapters.[13]

The Shū was designated one of the Five Classics when Confucian works made official by Emperor Wu of Han, and Jīng ("classic") was added to its name. The term Shàngshū ("esteemed documents") was also used in the Eastern Han.[14] The Xiping Stone Classics, set up outside the imperial academy in 175–183 but since destroyed, included a New Text version of the Documents.[15] Most Han dynasty scholars ignored the Old Text, and it disappeared by the end of the dynasty.[13]

"Recovered" Old Text

A version of the Old Text was allegedly rediscovered by the scholar Mei Ze during the 4th century, and presented to the imperial court of the Eastern Jin.[15] His version consisted of the 33 chapters of the New Text and an additional 25 chapters, with a preface and commentary purportedly written by Kong Anguo.[16] Mei's Old Text became widely accepted. It was the basis of the Shàngshū zhèngyì (尚書正義 "Correct interpretation of the Documents"), which was published in 653 and made the official interpretation of the Documents by imperial decree. The oldest extant copy of the text, included in the Kaicheng Stone Classics (833–837), contains all of these chapters.[15]

Since the Song dynasty, starting from Wú Yù (吳棫), many doubts had been expressed concerning the provenance of the allegedly rediscovered Old Text chapters of the book. In the 16th century, Méi Zhuó (梅鷟) published a detailed argument that these chapters, as well as the preface and commentary, were forged in the 3rd century AD using material from other historical sources such as the Zuo Commentary and the Records of the Grand Historian. Mei identified the sources from which the forger had cut and pasted text, and even suggested Huangfu Mi as a probable culprit. In the 17th century, Yan Ruoqu's unpublished but widely distributed manuscript entitled Evidential analysis of the Old Text Documents (尚書古文疏證 Shàngshū gǔwén shūzhèng) convinced most scholars that the rediscovered Old Text chapters were forged in the 3rd or 4th centuries.[17]

Modern discoveries

New light has been shed on the Book of Documents by the recovery between 1993 and 2008 of caches of texts written on bamboo slips from tombs of the state of Chu in Jingmen, Hubei.[18] These texts are believed to date from the late Warring States period, around 300 BC, and thus predate the burning of the books during the Qin dynasty.[18] The Guodian Chu Slips and the Shanghai Museum corpus include quotations of previously unknown passages of the work.[18][19] The Tsinghua Bamboo Slips includes the New Text chapter "Golden Coffer", with minor textual differences, as well as several documents in the same style that are not included in the received text. The collection also includes two documents that are versions of the Old Text chapters "Common Possession of Pure Virtue" and "Charge to Yue", confirming that the "rediscovered" versions are forgeries.[20]

Contents

In the orthodox arrangement, the work consists of 58 chapters, each with a brief preface traditionally attributed to Confucius, and also includes a preface and commentary, both purportedly by Kong Anguo. An alternative organization, first used by Wu Cheng, includes only the New Text chapters, with the chapter prefaces collected together, but omitting the Kong preface and commentary. In addition, several chapters are divided into two or three parts in the orthodox form.[16]

Nature of the chapters

With the exception of a few chapters of late date, the chapters are represented as records of formal speeches by kings or other important figures.[21][22] Most of these speeches are of one of five types, indicated by their titles:[23]

- Consultations (謨 mó) between the king and his ministers (2 chapters),

- Instructions (訓 xùn) to the king from his ministers (1 chapter),

- Announcements (誥 gào) by the king to his people (8 chapters),

- Declarations (誓 shì) by a ruler on the occasion of a battle (6 chapters), and

- Commands (命 mìng) by the king to a specific vassal (7 chapters).

Classical Chinese tradition lists six types of Shu, beginning with dian 典 (2 chapters in the Modern corpus).

According to Su Shi (1037–1101), it is possible to single out Eight Announcements of the early Zhou, directed to the Shang people. Their titles only partially correspond to the modern chapters marked as gao (apart of the nos. 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 that mention the genre, Su Shi names nos. 16 "Zi cai", 19 "Duo shi" and 22 "Duo fang").

As pointed out by Chen Mengjia (1911–1966), announcements and commands are similar, but differ in that commands usually include granting of valuable objects, land or servants to their recipients.

Guo Changbao 过常宝 (2008) claims that the graph gao (with "speech" radical, unlike 告 known since the OBI) presently appears on two bronze vessels (He zun and Shi Zhi gui 史[臣+舌]簋), as well as in the "six genres" 六辞 of the Zhou li (大祝) [24]

In many cases a speech is introduced with the phrase Wáng ruò yuē (王若曰 "The king seemingly said"), which also appears on commemorative bronze inscriptions from the Western Zhou period, but not in other received texts. Scholars interpret this as meaning that the original documents were prepared scripts of speeches, to be read out by an official on behalf of the king.[25][26]

Traditional organization

The chapters are grouped into four sections representing different eras: the semi-mythical reign of Yu the Great, and the three ancient dynasties of the Xia, Shang and Zhou. The first two sections – on Yu the Great and the Xia dynasty – contain two chapters each in the New Text version, and though they purport to record the earliest material in the Documents, from the 2nd millennium BC, most scholars believe they were written during the Warring States period. The Shang dynasty section contains five chapters, of which the first two – the "Speech of King Tang" and "Pan Geng" – recount the conquest of the Xia by the Shang and their leadership's migration to a new capital (now identified as Anyang). The bulk of the Zhou dynasty section concerns the reign of King Cheng of Zhou (r. c. 1040–1006 BC) and the kings's uncles, the Duke of Zhou and Duke of Shao. The last four New Text chapters relate to the later Western Zhou and early Spring and Autumn periods.[27]

| Part | New Text |

Orthodox chapter |

Title | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 虞書 Yu [Shun] |

1 | 1 | 堯典 | Yáo diǎn | Canon of Yao |

| 2 | 舜典 | Shùn diǎn | Canon of Shun | ||

| 3 | 大禹謨 | Dà Yǔ mó | Counsels of Great Yu | ||

| 2 | 4 | 皋陶謨 | Gāo Yáo mó | Counsels of Gao Yao | |

| 5 | 益稷 | Yì jì | Yi and Ji | ||

| 夏書 Xia |

3 | 6 | 禹貢 | Yǔ gòng | Tribute of [Great] Yu |

| 4 | 7 | 甘誓 | Gān shì | Speech at [the Battle of] Gan | |

| 8 | 五子之歌 | Wǔ zǐ zhī gē | Songs of the Five Sons | ||

| 9 | 胤征 | Yìn zhēng | Punitive Expedition on [King Zhongkang of] Yin | ||

| 商書 Shang |

5 | 10 | 湯誓 | Tāng shì | Speech of [King] Tang |

| 11 | 仲虺之誥 | Zhònghuī zhī gào | Announcement of Zhonghui | ||

| 12 | 湯誥 | Tāng gào | Announcement of [King] Tang | ||

| 13 | 伊訓 | Yī xùn | Instructions of Yi [Yin] | ||

| 14–16 | 太甲 | Tài jiǎ | Great Oath parts 1, 2 & 3 | ||

| 17 | 咸有一德 | Xián yǒu yī dé | Common Possession of Pure Virtue | ||

| 6 | 18–20 | 盤庚 | Pán Gēng | Pan Geng parts 1, 2 & 3 | |

| 21–23 | 說命 | Yuè mìng | Charge to Yue [of Fuxian] parts 1, 2 & 3 | ||

| 7 | 24 | 高宗肜日 | Gāozōng róng rì | Day of the Supplementary Sacrifice of King Gaozong [Wu Ding] | |

| 8 | 25 | 西伯戡黎 | Xībó kān lí | Chief of the West [King Wen]'s Conquest of [the State of] Li | |

| 9 | 26 | 微子 | Wēizǐ | [Prince] Weizi | |

| 周書 Zhou |

27–29 | 泰誓 | Tài shì | Great Speech parts 1, 2 & 3 | |

| 10 | 30 | 牧誓 | Mù shì | Speech at [the Battle of] Muye | |

| 31 | 武成 | Wǔ chéng | Successful Completion of the War [on Shang] | ||

| 11 | 32 | 洪範 | Hóng fàn | Great Plan [of Jizi] | |

| 33 | 旅獒 | Lǚ áo | Hounds of [the Western Tribesmen] Lü | ||

| 12 | 34 | 金滕 | Jīn téng | Golden Coffer [of Zhou Gong] | |

| 13 | 35 | 大誥 | Dà gào | Great Announcement | |

| 36 | 微子之命 | Wēizǐ zhī mìng | Charge to Prince Weizi | ||

| 14 | 37 | 康誥 | Kāng gào | Announcement to [Prince] Kang | |

| 15 | 38 | 酒誥 | Jiǔ gào | Announcement about Drunkenness | |

| 16 | 39 | 梓材 | Zǐ cái | Timber of Rottlera | |

| 17 | 40 | 召誥 | Shào gào | Announcement of Duke Shao | |

| 18 | 41 | 洛誥 | Luò gào | Announcement concerning Luoyang | |

| 19 | 42 | 多士 | Duō shì | Numerous Officers | |

| 20 | 43 | 無逸 | Wú yì | Against Luxurious Ease | |

| 21 | 44 | 君奭 | Jūn shì | Lord Shi [Duke Shao] | |

| 45 | 蔡仲之命 | Cài Zhòng zhī mìng | Charge to Cai Zhong | ||

| 22 | 46 | 多方 | Duō fāng | Numerous Regions | |

| 23 | 47 | 立政 | Lì zhèng | Establishment of Government | |

| 48 | 周官 | Zhōu guān | Officers of Zhou | ||

| 49 | 君陳 | Jūn chén | Lord Chen | ||

| 24 | 50 | 顧命 | Gù mìng | Testamentary Charge | |

| 51 | 康王之誥 | Kāng wáng zhī gào | Announcement of King Kang | ||

| 52 | 畢命 | Bì mìng | Charge to the [Duke of] Bi | ||

| 53 | 君牙 | Jūn Yá | Lord Ya | ||

| 54 | 冏命 | Jiǒng mìng | Charge to Jiong | ||

| 25 | 55 | 呂刑 | Lǚ xíng | [Marquis] Lü on Punishments | |

| 26 | 56 | 文侯之命 | Wén hóu zhī mìng | Charge to Marquis Wen [of Jin] | |

| 27 | 57 | 費誓 | Fèi shì | Speech at [the Battle of] Fei | |

| 28 | 58 | 秦誓 | Qín shì | Speech of [the Duke Mu of] Qin | |

Dating of the New Text chapters

Not all of the New Text chapters are believed to be contemporaneous with the events they describe, which range from the legendary emperors Yao and Shun to early in the Spring and Autumn period.[28] Six of these chapters concern figures prior to the first evidence of writing, the oracle bones dating from the reign of the late Shang king Wu Ding. Moreover, the chapters dealing with the earliest periods are the closest in language and focus to classical works of the Warring States period.[29]

The five announcements in the Documents of Zhou feature the most archaic language, closely resembling inscriptions found on Western Zhou bronzes in both grammar and vocabulary. Together with associated chapters such as "Lord Shi" and the "Testamentary Charge", the announcements are considered by most scholars to record speeches of King Cheng of Zhou, as well as the Duke of Zhou and Duke of Shao, uncles of King Cheng who were key figures during his reign (late 11th century BC).[30] They provide insight into the politics and ideology of the period, including the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven, explaining how the once-virtuous Xia had become corrupt and were replaced by the virtuous Shang, who went through a similar cycle ending in their replacement by the Zhou.[31] The "Timber of Rottlera", "Numerous Officers", "Against Luxurious Ease" and "Numerous Regions" chapters are believed to have been written somewhat later, in the late Western Zhou period.[32] A minority of scholars, pointing to differences in language between the announcements and Zhou bronzes, argue that they are products of a commemorative tradition in the late Western Zhou or early Spring and Autumn periods.[33][34]

Chapters dealing with the late Shang and the transition to Zhou use less archaic language. They are believed to have been modelled on the earlier speeches by writers in the Spring and Autumn period, a time of renewed interest in politics and dynastic decline.[32][35] The later chapters of the Zhou section are also believed to have been written around this time.[36] The "Pan Geng" chapter (later divided into three parts) seems to be intermediate in style between this group and the next.[37] It is the longest speech in the Documents, and is unusual in its extensive use of analogy.[38]

The chapters dealing with the legendary emperors, the Xia dynasty and the transition to Shang are very similar in language to such classics as The Mencius (late 4th century BC). They present idealized rulers, with the earlier political concerns subordinate to moral and cosmological theory, and are believed to be the products of philosophical schools of the late Warring States period.[35][37] Some chapters, particularly the "Tribute of Yu", may be as late as the Qin dynasty.[39][40]

Notable translations

- Gaubil, Antoine (1770). Le Chou-king, un des livres sacrés des Chinois, qui renferme les fondements de leur ancienne histoire, les principes de leur gouvernement & de leur morale; ouvrage recueilli par Confucius [The Shūjīng, one of the Sacred Books of the Chinese, which contains the Foundations of their Ancient History, the Principles of their Government and their Morality; Material collected by Confucius] (in French). Paris: N. M. Tillard.

- Medhurst, W. H. (1846). Ancient China. The Shoo King or the Historical Classic. Shanghai: The Mission Press.

- Legge, James (1865). The Chinese Classics, volume III: the Shoo King or the Book of Historical Documents. London: Trubner.; rpt. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1960. (Full Chinese text with English translation using Legge's own romanization system, with extensive background and annotations.)

- Legge, James (1879). The Shû king; The religious portions of the Shih king; The Hsiâo king. Sacred Books of the East 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Includes a minor revision of Legge's translation.

- Couvreur, Séraphin (1897). Chou King, Les Annales de la Chine [Shujing, the Annals of China] (in French). Hokkien: Mission Catholique. Reprinted (1999), Paris: You Feng.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1950). "The Book of Documents". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 22: 1–81. (New Text chapters only) Reprinted as a separate volume by Elanders in 1950.

- Katō, Jōken 加藤常賢 (1964). Shin kobun Shōsho shūshaku 真古文尚書集釈 [Authentic 'Old Text' Shàngshū, with Collected Commentary] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Meiji shoin.

- (Mandarin) Qu, Wanli 屈萬里 (1969). Shàngshū jīnzhù jīnyì 尚書今注今譯 [The Book of Documents, with Modern Annotations and Translation]. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan.

- Waltham, Clae (1971). Shu ching: Book of History. A Modernized Edition of the Translation of James Legge. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

- Ikeda, Suitoshi 池田末利 (1976). Shōsho 尚書 [Shàngshū] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shūeisha.

References

- ↑ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 327-378.

- ↑ Allan (2012), pp. 548–549, 551.

- ↑ Allan (2012), p. 550.

- ↑ Nylan (2001), p. 127.

- ↑ Lewis (1999), pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Schaberg (2001), p. 78.

- ↑ Nylan (2001), pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Nylan (2001), p. 130.

- 1 2 3 Shaughnessy (1993), p. 381.

- ↑ Nylan (1995), p. 26.

- ↑ Nylan (1995), pp. 28–36.

- ↑ Nylan (1995), p. 48.

- 1 2 Brooks (2011), p. 87.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2000), pp. 475–477.

- 1 2 3 Shaughnessy (1993), p. 383.

- 1 2 Shaughnessy (1993), pp. 376–377.

- ↑ Elman (1983), pp. 206–213.

- 1 2 3 Liao (2001).

- ↑ Shaughnessy (2006), pp. 56–58.

- ↑ "First Research Results on Warring States Bamboo Strips Collected by Tsinghua University Released". Tsinghua University News. Tsinghua University. May 26, 2011.

- ↑ Allan (2011), p. 3.

- ↑ Allan (2012), p. 552.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1993), p. 377.

- ↑ 论5尚书6诰体的文化背景

- ↑ Allan (2011), pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Allan (2012), pp. 552–556.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1993), pp. 378–380.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1993), pp. 377–380.

- ↑ Nylan (2001), pp. 133–135.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1999), p. 294.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1999), pp. 294–295.

- 1 2 Nylan (2001), p. 133.

- ↑ Kern (2009), pp. 146, 182–188.

- ↑ Vogelsang (2002), pp. 196–197.

- 1 2 Lewis (1999), p. 105.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1993), p. 380.

- 1 2 Nylan (2001), p. 134.

- ↑ Shih (2013), pp. 818–819.

- ↑ Nylan (2001), pp. 134, 158.

- ↑ Shaughnessy (1993), p. 378.

Works cited

- Allan, Sarah (2011), "What is a shu 書?" (PDF), EASCM Newsletter (4): 1–5.

- —— (2012), "On Shu 書 (Documents) and the origin of the Shang shu 尚書 (Ancient Documents) in light of recently discovered bamboo slip manuscripts", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 75 (3): 547–557, doi:10.1017/S0041977X12000547.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014). Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Brooks, E. Bruce (2011), "The Shu" (PDF), Warring States Papers 2: 87–90.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (1983), "Philosophy (i-li) versus philology (k'ao-cheng)—the jen-hsin Tao-hsin debate" (PDF), T'oung Pao 69 (4): 175–222, doi:10.1163/156853283x00081, JSTOR 4528296.

- Kern, Martin (2009), "Bronze inscriptions, the Shijing and the Shangshu: the evolution of the ancestral sacrifice during the Western Zhou" (PDF), in Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc, Early Chinese Religion, Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC to 220 AD), Leiden: Brill, pp. 143–200, ISBN 978-90-04-16835-0.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (1999), Writing and authority in early China, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-4114-5.

- Liao, Mingchun (2001), A Preliminary Study on the Newly-unearthed Bamboo Inscriptions of the Chu Kingdom: An Investigation of the Materials from and about the Shangshu in the Guodian Chu Slips (in Chinese), Taipei: Taiwan Guji Publishing Co., ISBN 957-0414-59-6.

- Nylan, Michael (1995), "The Ku Wen Documents in Han Times", T'oung Pao 81 (1/3): 25–50, doi:10.1163/156853295x00024, JSTOR 4528653.

- —— (2001), The Five "Confucian" Classics, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-08185-5.

- Schaberg, David (2001), A patterned past: form and thought in early Chinese historiography, Harvard Univ Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-00861-8.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1993). "Shang shu 尚書". In Loewe, Michael. Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute for East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 376–389. ISBN 978-1-55729-043-4.

- —— (1999), "Western Zhou history", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L., The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 292–351, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- —— (2006), Rewriting early Chinese texts, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-6643-8.

- Shih, Hsiang-lin (2013), "Shang shu 尚書 (Hallowed writings of antiquity)", in Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping, Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol. 2): A Reference Guide, Part Two Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 4 China, BRILL, pp. 814–830, ISBN 978-90-04-20164-4. line feed character in

|title=at position 84 (help) - Vogelsang, Kai (2002), "Inscriptions and proclamations: on the authenticity of the 'gao' chapters in the Book of Documents", Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 74: 138–209.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese history: a manual (2nd ed.), Harvard Univ Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

External links

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Book of Documents (Chinese) |

- 《尚書》 – Shang Shu at the Chinese Text Project, including both the Chinese text and Legge's English translation (emended to employ pinyin)

- Selections from Legge's Shu Jing (also emended)

- Annotated Edition of The Book of Documents

| ||||||||||||||||||||||