Boeing 737 Next Generation

| Boeing 737 Next Generation 737-600/-700/-800/-900 | |

|---|---|

| |

| SAS Boeing 737-800 | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner and Business jet |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing Commercial Airplanes |

| First flight | February 9, 1997 |

| Introduction | 1998 with Southwest Airlines |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Southwest Airlines Ryanair United Airlines Alaska Airlines |

| Produced | 1996–present |

| Number built | 5,423 as of December 2015[1] |

| Unit cost | |

| Developed from | Boeing 737 Classic |

| Variants | Boeing Business Jet Boeing 737 AEW&C Boeing C-40 Clipper Boeing P-8 Poseidon |

| Developed into | Boeing 737 MAX |

The Boeing 737 Next Generation, commonly abbreviated as 737NG,[3] is the name given to the −600/-700/-800/-900 series of the Boeing 737 airliner. It is the third generation derivative of the 737, and follows the 737 Classic (−300/-400/-500) series, which began production in the 1980s. They are short- to medium-range, narrow-body jet airliners. Produced since 1996 by Boeing Commercial Airplanes, the 737NG series includes four variants and can seat between 110 to 210 passengers.

A total of 5,419 737NG aircraft have been delivered by the end of May 2015, with more than 6,800 ordered.[1] The -700, -800, and -900ER have unfilled orders and are being produced, but orders for -600 and -900 have been filled.[1] The 737NG's primary competition is with the Airbus A320 family. Upgraded and re-engined models in development as the 737 MAX series will eventually supplant the 737NG.

Design and development

Background

Prompted by the development of the Airbus A320, which incorporated ground-breaking technologies such as fly-by-wire, in 1991 Boeing initiated development of an updated series of aircraft.[4] After working with potential customers, the 737 Next Generation (NG) program was announced on November 17, 1993.[5] The 737NG encompasses the −600, −700, −800 and −900 variants, and is to date the most significant upgrade of the airframe. The performance of the 737NG is essentially that of a new airplane, but important commonality is retained from previous 737 generations. The wing was modified, increasing its area by 25% and span by 16 ft (4.88 m), which increased the total fuel capacity by 30%. New quieter and more fuel-efficient CFM56-7B engines were used.[6] These improvements combine to increase the 737's range by 900 nmi, permitting transcontinental service.[5] A flight test program was operated by 10 aircraft: 3 -600s, 4 -700s, and 3 -800s.[5]

Interior

The passenger cabin of the 737 Next Generation improved on the previous style interior of the Boeing 757-200 and the Boeing 737 Classic by incorporating select features from the 777, with larger, more rounded overhead bins and curved ceiling panels. The interior of the 737 Next Generation also became the standard interior on the Boeing 757-300, and subsequently became optional on the 757-200.

In 2010, the interior of the 737 Next Generation was updated to look similar to that of the Boeing 787. Known as the Boeing Sky Interior, it introduces new pivoting overhead bins (a first for a Boeing narrowbody aircraft), new sidewalls, new passenger service units, and LED mood lighting. The Sky Interior cannot be retrofitted onto existing aircraft; however, similar aftermarket packages to simulate the look of the Sky Interior, including similar pivoting overhead bins for existing 737 and 757 aircraft are available from components provider Heath Tecna.[7] Boeing's Space Bins carry 50% more than the pivoting bins, allowing a 737 to hold 174 carry-on bags.[8]

Production and testing

The first NG to roll out was a −700, on December 8, 1996. This aircraft, the 2,843rd 737 built, first flew on February 9, 1997 with pilots Mike Hewett and Ken Higgins. The prototype −800 rolled out on June 30, 1997 and first flew on July 31, 1997, piloted by Jim McRoberts and again by Hewett. The smallest of the new variants, the −600 series, is identical in size to the −500, launching in December 1997 with an initial flight occurring January 22, 1998; it was granted FAA certification on August 18, 1998.[5][9]

Further developments

_departs_Bristol_Airport_23September2014_arp.jpg)

In 2004, Boeing offered a Short Field Performance package in response to the needs of Gol Transportes Aéreos, who frequently operate from restricted airports. The enhancements improve takeoff and landing performance. The optional package is available for the 737NG models and standard equipment for the 737-900ER.

In July 2008, Boeing offered Messier-Bugatti-Dowty's new carbon brakes for the Next-Gen 737s, which are intended to replace steel brakes and will reduce the weight of the brake package by 550–700 pounds (250–320 kg) depending on whether standard or high-capacity steel brakes were fitted. A weight reduction of 700 pounds (320 kg) on a Boeing 737-800 results in 0.5% reduction in fuel burn.[10] Delta Air Lines received the first Next-Gen 737 model with this brake package, a 737-700, at the end of July 2008.[11]

On August 21, 2006, Sky News alleged that Boeing's Next Generation 737s built from 1994 to 2002 contained defective parts. The report stated that various parts of the airframe produced by Ducommun were found to be defective by Boeing employees but that Boeing refused to take action. Boeing said that the allegations were "without merit".[12] However, a one-year investigation by Al Jazeera's People & Power series in 2010 questions the safety of some structural parts in 737s.[13]

Boeing increased 737 production from 31.5 to 35 per month in January 2012, to 38 per month in 2013, to 42 per month in 2014, and is planned to reach rates of 47 per month in 2017 and 52 per month in 2018.[14][15][16]

As early 737NG aircraft become available on the market they are actively marketed to be converted to cargo planes via the Boeing Converted Freighter design as the operational economics are attractive due to the low operating costs and availability of certified pilots on a robust airframe.

Replacement and re-engining

Since 2006, Boeing has discussed replacing the 737 with a "clean sheet" design (internally named "Boeing Y1") that could follow the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.[17] A decision on this replacement was postponed, and delayed into 2011.[18]

On July 20, 2011, Boeing announced plans for a new 737 version to be powered by the CFM International LEAP-X engine, with American Airlines intending to order 100 of these aircraft.[19] Internally, a minimum change version of the Leap-X is the probable final configuration for the proposed re-engined 737, and is expected to give a 10–12% improvement in fuel burn. A service entry in 2016 or 2017 is expected, with the new models probably being designated 737-7/-8/-9, being based on the 737-700/-800/-900ER respectively.[20]

On August 30, 2011, Boeing confirmed the launch of the 737 new engine variant, called the 737 MAX.[21] Its new CFM International LEAP-1B engines are expected to provide a 16% lower fuel burn than the current Airbus A320.[22][23] The 737 MAX is to compete with the Airbus A320neo.

Variants

737-600

The 737-600 is the direct replacement of the 737-500 and competes with the Airbus A318. The Boeing 737-600 did not include winglets as an option.[24] WestJet was to be the Boeing launch customer for the 737-600 winglets, but announced in their Q2 2006 results that they were not going to move ahead with those plans. The 737-600 was launched by Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) in 1995 with the first aircraft delivered on September 18, 1998. A total of 69 -600s have been produced and the final aircraft was delivered to WestJet in 2006.[1]

Since 2012, Boeing has removed the 737-600 from their list of aircraft prices.[2]

737-700

.jpg)

The 737-700 was the first of the Next Generation series when launch customer Southwest Airlines ordered the variant in November 1993. The variant was based on the 737-300 and entered service in 1998.[25] It replaced the 737-300 in Boeing's lineup, and its direct competitor is the Airbus A319. It typically seats 137 passengers in a two-class cabin or 149 in all-economy configuration. The primary user of the 737-700 series is Southwest Airlines.

The 737-700C is a convertible version where the seats can be removed to carry cargo instead. There is a large door on the left side of the aircraft. The United States Navy was the launch customer for the 737-700C under the military designation C-40 Clipper.[26]

737-700ER

_(4817611301).jpg)

Boeing launched the 737-700ER (ER for extended range) on January 31, 2006.[27] All Nippon Airways is the launch customer, with the first one of five 737-700ERs delivered on February 16, 2007. The 737-700ER is a mainline passenger version of the BBJ1 and 737-700IGW. It combines the 737-700 fuselage with the wings and landing gear of a 737-800. It offers a range of 5,510 nautical miles (10,200 km), with seating for 126 passengers in a traditional two-class configuration.[28] The 737-700ER competes with the Airbus A319LR. The 737-700ER has the second longest range for a 737 after the BBJ2. The 737-700ER is inspired by the Boeing Business Jet and is designed for long-range commercial applications.

All Nippon Airways began using the variant on daily service between Tokyo and Mumbai. ANA's service, believed to be the first all-business class route connecting to a developing country, was to start in September 2007 and use Boeing 737-700ERs outfitted with 38 (38 Club ANA) and 48 (24 Club ANA/24 Economy) in four-across seats configuration and an extra fuel tank.[29] As of November 2015, 1,116 -700, 117 -700 BBJ, 17 -700C, and 14 -700W aircraft have been delivered.[1]

737-800

The 737-800 is a stretched version of the 737-700, and replaces the 737-400. It also filled the gap left by the decision to discontinue the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 and MD-90 following Boeing's merger with McDonnell Douglas. The −800 was launched by Hapag-Lloyd Flug (now TUIfly) in 1994 and entered service in 1998. The 737-800 seats 162 passengers in a two-class layout, or 189 in one class, and competes with the A320. For many airlines in the U.S., the 737-800 replaced aging Boeing 727-200 trijets.

The 737-800 is also among the models replacing the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 series aircraft in airline service; it burns 850 US gallons (3,200 L) of jet fuel per hour, or about 80 percent of the fuel used by an MD-80 on a comparable flight, even while carrying more passengers than the latter.[30] According to the Airline Monitor, an industry publication, a 737-800 burns 4.88 US gallons (18.5 L) of fuel per seat per hour.[31]

On August 14, 2008, American Airlines announced 26 orders for the 737-800 (20 are exercised options from previously signed contracts and six are new incremental orders) as well as accelerated deliveries.[32] Ryanair, an Irish low-cost airline is among the largest operators of the Boeing 737-800, with a fleet of over 300 aircraft serving routes across Europe and North Africa. In November 2015, 3,849 -800, 55 -800A, and 21 -800 BBJ2 aircraft have been delivered with 1,093 unfilled orders.[1]

In 2011, United Airlines operated the first U.S. commercial flight powered by a blend of algae-derived biofuel and traditional jet fuel flying a Boeing 737-800 from Houston to Chicago to reduce its carbon footprint.[33]

737-900

Boeing later introduced the 737-900, the longest variant to date. Because the −900 retains the same exit configuration of the −800, seating capacity is limited to 189 in a high-density 1-class layout, although the 2-class number is higher at approximately 177. Alaska Airlines launched the 737-900 in 1997 and accepted delivery on May 15, 2001. The 737-900 also retains the MTOW and fuel capacity of the −800, trading range for payload. These shortcomings until recently prevented the 737-900 from effectively competing with the Airbus A321.

737-900ER

The 737-900ER (ER for extended range), which was called the 737-900X prior to launch, is the newest addition and the largest variant of the Boeing 737 line and was introduced to meet the range and passenger capacity of the discontinued 757-200 and to directly compete with the Airbus A321. An additional pair of exit doors and a flat rear pressure bulkhead increased seating capacity to 180 passengers in a 2-class configuration or 220[34] passengers in a single-class layout. Additional fuel capacity and standard winglets improved range to that of other 737NG variants.

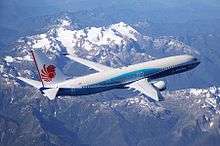

The first 737-900ER was rolled out of the Renton, Washington factory on August 8, 2006 for its launch customer, Lion Air. Lion Air received this aircraft on April 27, 2007 in a special dual paint scheme combining the Lion Air's logo on the vertical stabilizer and the Boeing's livery colors on the fuselage. Lion Air has orders for 132 Boeing 737-900ERs as of August 2015.[1]

On August 22, 2011, it was reported that Delta Air Lines placed an order for 100 737-900ERs.[35] As of November 2015, 52 -900s, 358 -900ERs, and 7 -900 BBJ3s have been delivered with 142 unfilled orders.[1]

Military models

- Boeing 737 AEW&C – The Boeing 737 AEW&C is a 737-700IGW roughly similar to the 737-700ER. This is an Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) version of the 737NG. Australia is the first customer (as Project Wedgetail), followed by Turkey and South Korea.

- C-40 Clipper – The C-40A Clipper is a 737-700C used by the U.S. Navy as a replacement for the C-9B Skytrain II. The C-40B and C-40C are used by the US Air Force for transport of generals and other senior leaders.

- P-8 Poseidon – The P-8 is a 737-800ERX ("Extended Range") that was selected on June 14, 2004 to replace the Lockheed P-3 Orion maritime patrol aircraft.[36] The P-8 is unique in that it has 767-400ER-style raked wingtips, instead of the blended winglets available on 737NG variants. The P-8 is designated 737-800A by Boeing.[37]

Boeing Business Jet

Plans for a business jet version of the 737 are not new. In the late 1980s, Boeing marketed the Boeing 77–33 jet, a business jet version of the 737-300.[38] The name was short-lived. After the introduction of the next generation series, Boeing introduced the Boeing Business Jet (BBJ) series. The BBJ1 was similar in dimensions to the 737-700 but had additional features, including stronger wings and landing gear from the 737-800, and has increased range (through the use of extra fuel tanks) over the other various 737 models. The first BBJ rolled out on August 11, 1998 and flew for the first time on September 4.[39]

On October 11, 1999 Boeing launched the BBJ2. Based on the 737-800, it is 5.84 m (19 ft 2 in) longer than the BBJ1, with 25% more cabin space and twice the baggage space, but has slightly reduced range. It is also fitted with auxiliary belly fuel tanks and winglets. The first BBJ2 was delivered on February 28, 2001.[39]

Operators

As of July 2015, 5102 Boeing 737 Next Generation aircraft were in commercial service. This includes 57 -600s, 1036 -700s, 3629 -800s and 380 -900s.[40]

Orders and deliveries

| Model Series | Orders | Deliveries | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Jets | Total | Unfilled | Total | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 |

| 737-600 | 69 | 69 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 24 | 8 | |||||||||||

| 737-700 | 1,151 | 35 | 1,116 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 43 | 23 | 51 | 61 | 101 | 103 | 93 | 109 | 80 | 71 | 85 | 75 | 96 | 85 | 3 |

| 737-700C | 20 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 737-700W | 14 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 737-800 | 4,978 | 1,096 | 3,882 | 396 | 386 | 347 | 351 | 292 | 323 | 283 | 190 | 214 | 172 | 104 | 78 | 69 | 126 | 168 | 185 | 133 | 65 | |

| 737-800A | 82 | 26 | 56 | 15 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 737-900 | 52 | 52 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 21 | |||||||||||||||

| 737-900ER | 518 | 158 | 360 | 73 | 70 | 67 | 44 | 24 | 15 | 28 | 30 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Total | 6,884 | 1,318 | 5,566 | 491 | 482 | 434 | 411 | 365 | 366 | 367 | 284 | 324 | 291 | 208 | 199 | 167 | 213 | 281 | 269 | 253 | 158 | 3 |

| Business Jet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BBJ 737-700 | 121 | 2 | 119 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 13 | 11 | 25 | 8 | |

| BBJ 737-800 | 21 | 21 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||||||||||

| BBJ 737-900 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 149 | 2 | 147 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 18 | 11 | 25 | 8 | |

| Grand Total | 7,033 | 1,320 | 5,713 | 495 | 485 | 440 | 415 | 372 | 376 | 372 | 290 | 330 | 302 | 212 | 202 | 173 | 223 | 299 | 280 | 278 | 166 | 3 |

Data through December 31, 2015. Updated on January 13, 2016.[1]

Accidents and incidents

According to the Aviation Safety Network, the Boeing 737 Next Generation series has been involved in 14 hull-loss accidents and 10 hijackings, for a total of 527 fatalities.[41][42][43][44]

- Notable accidents and incidents

- December 8, 2005 – Southwest Airlines Flight 1248, a 737-700, skidded off a runway upon landing at Chicago Midway International Airport in heavy snow conditions. A six-year-old boy died in a car struck by the airliner after it skidded into a street. People on board the aircraft and on the ground reported several minor injuries. The aircraft involved, N471WN, became N286WN after repairs.

- September 29, 2006 – Gol Transportes Aéreos Flight 1907, a 737-800 Brazilian airliner with 154 people on board broke up and crashed following a midair collision with an Embraer Legacy 600. All on board the 737-800 were killed. The Legacy landed safely at a Brazilian Air Force Base.[45]

- May 5, 2007 – Kenya Airways Flight 507, a 737-800 carrying 105 passengers and nine crew lost contact and crashed into a swamp on a flight to Nairobi, Kenya from Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, after making a scheduled stop at Douala, Cameroon. There were no survivors.

- August 20, 2007 – China Airlines Flight 120, a Boeing 737-800 inbound from Taipei, caught fire shortly after landing at Naha Airport in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. There were no fatalities. Following this incident, the FAA issued an Emergency Airworthiness Directive (EAD) on August 25 ordering inspection of all Boeing 737NG series aircraft for loose components in the wing leading edge slats within 24 days. On August 28, after initial reports from these inspections, the FAA issued a further EAD requiring a detailed or borescope inspection within 10 days, and an explicit tightening of a nut-and-bolt assembly within 24 days.[46]

- November 10, 2008 – Ryanair Flight 4102, a Boeing 737-800 from Frankfurt-Hahn suffered substantial damage in an emergency landing at Rome Ciampino Airport. The cause of the accident was stated to be birdstrikes affecting both engines. The port undercarriage of the 737 collapsed.[47] The aircraft involved was Boeing 737-8AS EI-DYG (c/n33639, msn 2557). Of the six crew and 166 passengers on board,[48] two crew and eight passengers were taken to hospital with minor injuries.[49] As well as damage to the engines and undercarriage, the rear fuselage was also damaged by contact with the runway.[50]

- February 25, 2009 – Turkish Airlines Flight 1951, a Boeing 737-800 coming from Istanbul, crashed during landing into a field near the Polderbaan at Schiphol airport, Amsterdam. The fuselage broke into three pieces after the crash and the engine pylons separated. Of the 135 passengers and crew, there were nine fatalities: five passengers and four crew members (including both pilots and a pilot-in-training), and 84 people suffered injuries. Crash investigations initially focused on a malfunctioning left radio altimeter, which may have resulted in false altitude information causing the autothrottle to reduce power.[51]

- December 22, 2009 – American Airlines Flight 331, a 737-800 (registration N977AN) overran the runway at Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston, Jamaica. The aircraft, registration N977AN, overran the runway during a landing hampered by poor weather. The plane continued on the ground outside the airport perimeter and broke apart causing injuries. All 154 persons on board survived.

- January 25, 2010 – Ethiopian Airlines Flight 409, a 737-800, crashed into the Mediterranean Sea shortly after take-off from Beirut Rafic Hariri International Airport. The flight had 90 passengers and 8 crew, 50 passengers of which were Lebanese, and was bound for the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa. There were no survivors.[52][53]

- May 22, 2010 – Air India Express Flight 812, a 737-800, overran the runway on landing at Mangalore International Airport, killing 158 passengers including six crew on board. There were eight survivors. The airliner overran beyond the middle of the runway hitting the antenna and crashed through the fence at the end of the runway going into the valley 200 feet below. Although the 8,000 ft runway is sufficient for landing there was no bare land at the end of the runway on the table top airport to account for mistakes.[54][55][56]

- August 16, 2010 – AIRES Flight 8250, a 737-700, crashed and split into three pieces on the Colombian island of San Andres. There was no fire and two fatalities reported.[57]

- January 5, 2011 – an attempt was made to hijack Turkish Airlines Flight 1754 from Gardermoen Airport, Oslo to Ataturk International Airport, Istanbul. The hijacker was overpowered by other passengers on the flight and was arrested when the aircraft landed.[58] The flight was being operated by Boeing 737-800 TC-JGZ.[59]

- July 30, 2011 – Caribbean Airlines Flight 523, a 737-800, overran the runway in rainy weather and crashed through the perimeter fence while landing at the Cheddi Jagan International Airport in Guyana. The aircraft broke into two at around the first class area. There were no fatalities, but several passengers were injured with at least two passengers suffering broken legs.[60][61][62] Caribbean Airlines confirmed 157 passengers and 6 crew members were on board.[63]

- April 13, 2013 – Lion Air Flight 904, a 737-800 (registration PK-LKS) from Bandung to Denpasar (Indonesia) with 108 people onboard, undershot runway 09 and crashed into the sea while landing at Ngurah Rai International Airport. The aircraft’s fuselage ruptured slightly near the wings. All passengers and crew were safely evacuated with only minor injuries.[64]

Specifications

| 737-600 | 737-700 / 737-700ER |

737-800 | 737-900ER | 737-700C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | ||||

| Seating capacity[65] | 149 (1-class, maximum) 123 (1-class, typical) 108 (2-class, typical) | 149 (1-class, dense) 140 (1-class, typical) 128 (2-class, typical) | 189 (1-class, dense) 175 (1-class, typical) 160 (2-class, typical) | 220 (1-class high density, maximum certificated)[66] 204 (1-class, typical) 174 (2-class, typical) | up to 149 (all-passenger layout) |

| Seat pitch | 30 in (76 cm) (1-class, dense) 32 in (81 cm) (1-class, typical) 36 in (91 cm) & 32 in (81 cm) (2-class, typical) | 28 in (71 cm) (1-class, high density) 30 in (76 cm) (1-class, dense) 36 in (91 cm) & 32 in (81 cm) (2-class, typical) | |||

| Seat width | 17.2 in (44 cm) (1-class, 6 abreast seating) | ||||

| Overall length | 102 ft 6 in (31.2 m) | 110 ft 4 in (33.6 m) | 129 ft 6 in (39.5 m) | 138 ft 2 in (42.1 m) | 110 ft 4 in (33.6 m) |

| Wingspan | 117 ft 5 in (35.7 m) | 112 ft 7 in (34.3 m) | |||

| Overall height | 41 ft 3 in (12.6 m) | 41 ft 2 in (12.5 m) | |||

| Wing sweepback | 25.02° (437 mrad) | ||||

| Wing aspect ratio | 9.45 | ||||

| Fuselage width | 12 ft 4 in (3.76 m) | ||||

| Fuselage Height | 13 ft 2 in (4.01 m) | ||||

| Maximum cabin width | 11 ft 7 in (3.54 m) | ||||

| Cabin height | 7 ft 3 in (2.20 m) | ||||

| Operating empty weight | 80,031 lb (36,378 kg) | 84,100 lb (38,147 kg) | 91,108 lb (41,413 kg) | 98,495 lb (44,676 kg) | 83,000 lb (37,648 kg) |

| Maximum landing weight[65] | 120,500 lb (54,658 kg) | 134,000 lb (60,781 kg) | 146,300 lb (66,361 kg) | 157,300 lb (71,350 kg) | 129,200 lb (58,604 kg) |

| Maximum take-off weight | 145,500 lb (66,000 kg) | Basic: 154,500 lb (70,080 kg) ER: 171,000 lb (77,565 kg) | 174,200 lb (79,010 kg) | 187,700 lb (85,130 kg) | 171,000 lb (77,560 kg) |

| Cargo capacity | 756 ft³ (21.4 m³) | 966 ft³ (27.3 m³) | 1,591 ft³ (45.1 m³) | 1,852 ft³ (52.5 m³) | up to 3,800 ft³ (107.6 m³) up to 40,000 lb (18,200 kg) (all-cargo layout) |

| Takeoff run at MTOW (sea level, ISA) |

5,741 ft (1,750 m) | Basic: 5,249 ft (1,600 m) ER: 6,890 ft (2,100 m) | 7,874 ft (2,400 m) | 9,843 ft (3,000 m) | |

| Service ceiling | 41,000 ft (12,500 m) | ||||

| Cruising speed | Mach 0.785 (447 kn, 514 mph, 828 km/h) | Mach 0.78 (444 kn, 511 mph, 823 km/h) | Mach 0.785 (447 kn, 514 mph, 828 km/h) | ||

| Maximum speed | Mach 0.825 (475 kn, 545 mph, 877 km/h) | Mach 0.82 (471 kn, 541 mph, 871 km/h) | |||

| Range fully loaded | Basic: 3,050 nmi (5,648 km) WL: 3,225 nmi (5,970 km) | Basic: 3,365 nmi (6,230 km) WL: 3,440 nmi (6,370 km) ER: 5,775 nmi (10,695 km) in 1 class layout with 9 aux. tanks | Basic: 3,060 nmi (5,665 km) WL: 3,115 nmi (5,765 km) | Basic: 2,700 nmi (4,996 km) in 1 class layout Basic: 3,200 nmi (5,925 km) in 2 class layout with 2 aux. tanks WL: 3,265 NM (6,045 km) in 2 class layout with 2 aux. tanks | Cargo: 3,000 nmi (5,555 km) Passenger: 3,285 nmi (6,080 km) |

| Max. fuel capacity | Non-ER: 6,875 US gal (26,020 L) ER:[67] 10,707 US gal (40,530 L) | 7,837 US gal (29,660 L) | 6,875 US gal (26,020 L) | ||

| Engine (× 2) | CFM 56-7B20 | CFM 56-7B26 | CFM 56-7B27 | CFM56-7 | |

| Max. thrust (× 2) | 22,700 lbf (101.0 kN) | 26,300 lbf (117.0 kN) | 27,300 lbf (121.4 kN) | 27,300 lbf (121.4 kN) | |

| Cruising thrust (× 2) | 5,210 lbf (23.18 kN) | 5,480 lbf (24.38 kN) | |||

| Fan tip diameter | 61 in (1.55 m) | ||||

| Engine length | 98.7 in (2.51 m) | ||||

| Engine ground clearance | 18 in (46 cm) | 19 in (48 cm) | |||

Sources: Boeing 737 Specifications,[68][69] 737 Airport Planning Report[65]

See also

- Related development

- Boeing 737

- Boeing 737 Classic

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing T-43

- Boeing Business Jet

- Boeing 737 AEW&C

- C-40 Clipper

- P-8 Poseidon

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Airbus A320 family

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 757

- Bombardier CSeries

- Comac C919

- Embraer 195

- Irkut MS-21

- McDonnell Douglas MD-90

- Tupolev Tu-204

- Related lists

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "737 Model Orders and Deliveries data." Boeing, December 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Commercial Airplanes – Jet Prices". www.boeing.com. Boeing. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ↑ "737NG: The Next Generation for Japan and the world". Boeingblogs.com. 2005-02-04. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Endres 2001, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Shaw 1999, p. 8

- ↑ Endres 2001, p. 133.

- ↑ "Heath Tecna to Trial Project Amber Interior in 737NG Fleet with Qantas". ADS News, July 10, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ↑ Perry, Dominic (7 April 2015), "Boeing thinks smarter to boost 777, 737 appeal", Flightglobal (Reed Business Information), retrieved 8 April 2015

- ↑ Shaw 1999, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Wilhelm, Steve. "Mindful of rivals, Boeing keeps tinkering with its 737." Puget Sound Business Journal, August 11, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Boeing Next-Generation 737 Carbon Brakes Earn FAA Certification." Boeing Press Release, August 4, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Report alleges faulty parts in jets." United Press International, August 21, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ↑ "Boeing Safety Claims Investigated". Al Jazeera English via youtube.com, December 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Boeing ups 737 production rate." Flightglobal.com, September 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Boeing to Increase 737 Production Rate to 52 per Month in 2018." Boeing., October 2, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "737 derailment probe 'suggests' track alignment issue." Flightglobal.com, November 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Boeing firms up 737 replacement studies by appointing team." Flight International, March 3, 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ Hamilton, Scott. "737 decision may slip to 2011: Credit Suisse." flightglobal, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Boeing and American Airlines Agree on Order for up to 300 Airplanes". Boeing, July 20, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ↑ Ostrower, Jon. "Boeing close to re-engined 737 fan size decision." Air Transport Intelligence news via FlightGlobal.com, August 18, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ↑ Boeing 737 MAX. NewAirplane.com

- ↑ "Boeing Launches 737 New Engine Family with Commitments for 496 Airplanes from Five Airlines." Boeing August 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Boeing officially launches re-engined 737." flightglobal.com, August 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Next-Generation 737 Production Winglets." boeing.com. Retrieved February 10, 2008. Archived April 28, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Boeing 737-600/700." airliners.net. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ↑ "U.S. Naval Reserve Gets First Look at Newest Class of Aircraft." DefenseLink (U.S. Department of Defense). Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Boeing Launches Longest-Range 737 with ANA.". Boeing.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "Boeing 737-700ER Technical Information". Boeing

- ↑ "Press release". Ana.co.jp. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Wallace, James. "Aerospace Notebook: MD-80 era winding down as fuel costs rise." Seattlepi.com, June 24, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ Wilhelm, Steve. "Mindful of rivals, Boeing keeps tinkering with its 737." Orlando Business Journal, August 11, 2008 Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Boeing, American Airlines Finalize Deal for 26 Next-Generation 737s." Boeing Press Release, August 14, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009. Archived August 18, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Commercial airlines industry mixed on imminent emission regulations". CNN, June 4, 2015.

- ↑ FAA Type Certificate Data Sheet http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgMakeModel.nsf/0/9dd07e4b4293722e86257dfc006774ca/$FILE/A16WE_Rev_54.pdf

- ↑ "Air Transport Intelligence news: Delta to cap its narrowbody order at 100 737-900ERs." Flightglobal, August 22, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ↑ "P-8A Multi-mission Maritime Aircraft (MMA) fact file." US Navy, February 17, 2009.

- ↑ "FARNBOROUGH 2008: Boeing 737 embarks on its Poseidon adventure". Flight International, July 15, 2008.

- ↑ Endres 2001

- 1 2 "The Boeing 737-700/800 BBJ/BBJ2." airliners.net, February 3, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ https://d1fmezig7cekam.cloudfront.net/VPP/Global/Flight/Airline%20Business/AB%20home/Edit/WorldAirlinerCensus2015.pdf

- ↑ "Accident statistics for Boeing 737-600." aviation-safety.net. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Accident statistics for Boeing 737–700." aviation-safety.net. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Accident statistics for Boeing 737–800." aviation-safety.net. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Accident statistics for Boeing 737–900." aviation-safety.net Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident description Boeing 737-8EH PR-GTD – Peixoto Azevedo, MT." aviation-safety.net, September 29, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "FAA orders quicker 737 wing inspections." Flightglobal.com, August 29, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Bird-hit jet in emergency landing." BBC News Online, November 11, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Accident description." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ↑ Hradecky, Simon. "Accident: Ryanair B738 at Rome on Nov 10th 2008, engine and landing gear trouble, temporarily departed runway." The Aviation Herald, November 11, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ Kaminski-Morrow, David. "Pictures: Bird-struck Ryanair 737 extensively damaged." flightglobal.com. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- ↑ Kaminski-Morrow, David. "Crashed Turkish 737's thrust fell after sudden altimeter step-change." flightglobal.com, April 3, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Ethiopian plane crashes off Beirut, 90 feared dead." Reuters, January 25, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Ethiopian Airlines plane crashes into Mediterranean sea." The Daily Telegraph, January 25, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Jetliner crash in India, airline says." CNN, May 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Indian official: At least 160 dead in Air India plane crash in Mangalore ." Wire Update/BNO News, May 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Casualties feared in Air India crash." CNN, May 22, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ Uphoff, Rainer. "Aires 737-700 crashes on landing in San Andres." flightglobal.com, August 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Passengers thwart Turkish jet hijack attempt." BBC News Online, January 6, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ↑ Hradecky, Simon. "Incident: THY B738 near Istanbul on Jan 5th 2011, hijack attempt averted." Aviation Herald, January 5, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Terror at CJIA: Caribbean Airlines plane crashes on landing." Kaieteur News with pictures. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ↑ BERT WILKINSON - Associated Press July 30, 2011 (2011-07-30). "Commercial plane crashes in Guyana; no deaths – Yahoo! News". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "All survive airliner crash in Georgetown, Guyana | CTV News". Ctv.ca. 2011-07-30. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "News Releases." Caribbean Airlines. Retrieved August 29, 2012. Archived September 3, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Lion Air Passenger Plane Crashes in Bali". April 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Boeing 737 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning, Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

- ↑ FAA Type Certificate Data Sheet http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgMakeModel.nsf/0/9c59427a20b3253686257d03004d8faa/$FILE/A16WE_Rev_53.pdf

- ↑ "737-700ER Technical Characteristics". Boeing. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ http://www.boeing.com/assets/pdf/commercial/airports/acaps/737sec2.pdf

- ↑ Boeing 737 Technical Information, Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Bibliography

- Endres, Günter. The Illustrated Directory of Modern Commercial Aircraft. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1125-0.

- Norris, Guy and Mark Wagner. Modern Boeing Jetliners. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, 1999. ISBN 9780760307175.

- Shaw, Robbie. Boeing 737–300 to 800. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0699-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boeing 737 Next Generation. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 7x7 aircraft production timeline, 1955–present | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Boeing 707 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 720 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 717 (MD-95) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 727 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 737 Original | Boeing 737 Classic | Boeing 737 NG | Boeing 737 MAX | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 747 (Boeing 747SP) | Boeing 747-400 | 747-8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 757 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 767 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 777 | Boeing 777X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 787 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| = Narrow-body | = Wide-body | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||