Bochum

| Bochum | |||

|---|---|---|---|

_2010-08-12_050.jpg) | |||

| |||

Bochum | |||

| Coordinates: 51°28′55″N 07°12′57″E / 51.48194°N 7.21583°ECoordinates: 51°28′55″N 07°12′57″E / 51.48194°N 7.21583°E | |||

| Country | Germany | ||

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia | ||

| Admin. region | Arnsberg | ||

| District | Urban districts of Germany | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Thomas Eiskirch (SPD) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 145.4 km2 (56.1 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2014-12-31)[1] | |||

| • Total | 361,876 | ||

| • Density | 2,500/km2 (6,400/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | ||

| Postal codes | 44701-44894 | ||

| Dialling codes | 0234, 02327 | ||

| Vehicle registration | BO, WAT | ||

| Website | www.bochum.de | ||

Bochum (German pronunciation: [ˈboːxʊm]; Westphalian: Baukem) is a city in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany and part of the Arnsberg region. It is located in the Ruhr area and is surrounded by the cities (in clockwise direction) of Herne, Castrop-Rauxel, Dortmund, Witten, Hattingen, Essen and Gelsenkirchen. With a population of nearly 365,000, it is the 16th most populous city in Germany.

Geography

Geographical position

The city lies on the low rolling hills of Bochum land ridge (Bochumer Landrücken), part of the Ruhrhöhen (highest elevations) between the Ruhr and Emscher rivers at the border of the southern and northern Ruhr coal region. The highest point of the city is at Kemnader Straße (Kemnader Street) in Stiepel at 196 metres above sea level; the lowest point is 43 metres at the Blumenkamp in Hordel.

The terrain of Bochum is characterised by rolling hills that rarely have more than three per cent graduation. Steeper graduation can be found at the Harpener Hellweg near the Berghofer Holz nature reserve (3.4%), at Westenfelder Straße (Westenfelder Street) in the borough of Wattenscheid (3.47%), or at Kemnader Straße, which begins at the banks of the Ruhr in Stiepel (71 metres a.s.l.), and rises to its highest point in the centre of Stiepel (196 metres a.s.l., a 5.1% increase).

The city extends north to south 13 km and 17.1 km east to west. The circumference of the city limits is 67.2 km.

Geology

There is sedimentary rock of carbon and chalk. The geological strata can be visited in the former quarry of the Zeche Klosterbusch (Klosterbusch mine) and at the Geologischer Garten Bochum (Bochum Geological Gardens).

Waterways

The urban area is divided into the river Ruhr catchment in the south and the Emscher catchment in the north. The Ruhr tributaries are the Oelbach (where as well a waste water treatment plant is established[2]), Gerther Mühlenbach, Harpener Bach, Langendreer Bach, Lottenbach, Hörsterholzer Bach and the Knöselbach. The Ruhr in combination with upstream reservoirs is also used for drinking water abstraction. The Emscher tributaries are Hüller Bach with Dorneburger Mühlenbach, Hofsteder Bach, Marbach, Ahbach, Kabeisemannsbach and Goldhammer Bach. The industrial developements in the region since the 19th century were leading to a kind of division of labour between the 2 river catchments, pumping drinking water from the Ruhr into the municipal supply system and discharging waste water mainly into the Emscher system. Today approximately 10% of the waste water in the Emscher catchment is discharged via the Hüller Bach.[3] and treated in the centralized waste water treatment plant of the Emschergenossenschaft in Bottrop. The ecological restoration of the Emscher tributaries initiated by the Emschergenossenschaft started with the Internationale Bauausstellung Emscher Park in 1989.

Vegetation

The city's south has woods, the best known of which are the Weitmarer Holz. These are generally mixed forests of oak and beech. The occurrence of holly gives evidence of Bochum's temperate climate.

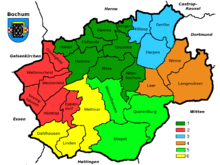

Districts

Bochum is divided into six administrative districts with a total of 362,213 inhabitants living in an urban area of 145.4 km2.

- Bochum-Mitte includes Innenstadt, Hamme (including Goldhamme, and Stahlhausen), Hordel, Hofstede, Riemke, Grumme and Altenbochum. There are 102,145 inhabitants living in an area of 32.60 km².

- Wattenscheid includes Wattenscheid-Mitte, Leithe, Günnigfeld, Westenfeld, Sevinghausen, Höntrop, Munscheid and Eppendorf (which includes Engelsburg and Heide). There are 74,602 inhabitants living in an area of 23.87 km².

- North includes Bergen, Gerthe, Harpen (including Rosenberg), Kornharpen, Hiltrop and Voede-Abzweig. There are 37,004 inhabitants living in an area of 18.86 km².

- East includes Laer, Werne, and Langendreer (including Ümmingen and Kaltehardt). There are 55,193 inhabitants living in an area of 23.46 km².

- South includes Wiemelhausen (which includes Brenschede, and Ehrenfeld), Stiepel (which includes Haar, Brockhausen, and Schrick) and Querenburg (which includes Hustadt and Steinkuhl). There are 50,866 inhabitants living in an area of 27.11 km².

- Southwest includes Weitmar (which includes Bärendorf, Mark, and Neuling), Sundern, Linden and Dahlhausen. There are 56,510 inhabitants living in an area of 19.50 km².

History

Bochum dates from the 9th century, when Charlemagne set up a royal court at the junction of two important trade routes. It was first officially mentioned in 1041 as Cofbuokheim in a document of the archbishops of Cologne. In 1321, Count Engelbert II von der Marck granted Bochum a town charter, but the town remained insignificant until the 19th century, when the coal mining and steel industries emerged in the Ruhr area, leading to the growth of the entire region. The population of Bochum increased from about 4,500 in 1850 to 100,000 in 1904. Bochum acquired city status, incorporating neighbouring towns and villages. Additional population gains came from immigration, primarily from Poland.

After the war, the new state of North Rhine-Westphalia was established, consisting of the Rhineland and Westphalia. Bochum is located in that state.

In the postwar period, Bochum began developing as a cultural centre of the Ruhr area. In 1965, the Ruhr University was opened, the first modern university in the Ruhr area and the first to be founded in Germany since World War II. Since the seventies, Bochum's industry has moved from heavy industry to the service sector. Between 1960 and 1980, the coal mines all closed. Other industries, such as automotive, compensated for the loss of jobs. The Opel Astra is assembled at the Opel Bochum plant; however, by 2009, the factory was in serious financial difficulties[4] and in December 2012, Opel announced that Opel will stop vehicle production Bochum plant in 2016.[5]

In the course of a comprehensive community reform in 1975, Wattenscheid, a formerly independent city, was integrated into the city of Bochum. A local referendum against the integration failed. In 2007, the new synagogue of the Jewish community of Bochum, Herne und Hattingen was opened. In 2008, Nokia closed down its production plant, causing the loss of thousands of jobs, both at the plant and at local suppliers. 20,000 people showed up to protest against the closing.[6][7] Within months, the Canadian high-tech company, Research in Motion, announced plans to open a research facility, its first outside Canada, adding several hundred jobs.[8][9][10]

The Nazi era and World War II

On 9 November 1938, Kristallnacht, the Jewish citizens of Bochum were attacked. The synagogue was set on fire and there was rioting against Jewish citizens. The first Jews from Bochum were deported to Nazi concentration camps and many Jewish institutions and homes were destroyed. Some 500 Jewish citizens are known by name to have been killed in the Holocaust, including 19 who were younger than 16 years old. Joseph Klirsfeld was Bochum's rabbi at this time. He and his wife fled to Palestine. In December 1938, the Jewish elementary school teacher Else Hirsch began organising groups of children and adolescents to be sent to the Netherlands and England, sending ten groups in all. Many Jewish children and those from other persecuted groups were taken in by Dutch families and thereby saved from abduction or deportation and death.[11]

Because the Ruhr region was an area of high residential density and a centre for the manufacture of weapons, it was a major target in the war. Women with young children, school children and the homeless fled or were evacuated to safer areas, leaving cities largely deserted to the arms industry, coal mines and steel plants and those unable to leave.

Bochum was first bombed heavily in May and June 1943.[12] On 13 May 1943, the city hall was hit, destroying the top floor, and leaving the next two floors in flames. On 4 November 1944, in an attack involving 700 British bombers, the steel plant, Bochumer Verein, was hit. One of the largest steel plants in Germany,[13] more than 10,000 high-explosive and 130,000 incendiary bombs were stored there, setting off a conflagration that destroyed the surrounding neighbourhoods.[14][15] An aerial photo shows the devastation.[16]

The town centre of Bochum was a strategic target during the Oil Campaign. In 150 air raids on Bochum, over 1,300 bombs were dropped on Bochum and Gelsenkirchen. By the end of the war, 38% of Bochum had been destroyed. 70,000 citizens were homeless and at least 4,095 dead.[15][17] Of Bochum's more than 90,000 homes, only 25,000 remained for the 170,000 citizens who survived the war, many by fleeing to other areas. Most of the remaining buildings were damaged, many with only one usable room. Only 1,000 houses in Bochum remained undamaged after the war. Only two of 122 schools remained unscathed; others were totally destroyed. Hunger was rampant. A resident of neighbouring Essen was quoted on 23 April 1945 as saying, "Today, I used up my last potato... it will be a difficult time till the new [autumn] potatoes are ready to be picked – if they're not stolen."[18][19]

The Allied ground advance into Germany reached Bochum in April 1945. Encountering desultory resistance, the US 79th Infantry Division captured the city on 10 April 1945.[20]

After the war, Bochum was occupied by the British, who established two camps to house people displaced by the war. The majority of them were former Polish Zwangsarbeiter, forced labourers, many of them from the Bochumer Verein.[21]

More than sixty years after the war, bombs continue to be found in the region, usually by construction workers. One found in October 2008 in Bochum town centre led to the evacuation of 400 and involved hundreds of emergency workers.[22] A month earlier, a buried bomb exploded in neighbouring Hattingen, injuring 17 people.[23]

| Largest groups of foreign residents[24] | |

| Nationality | Population (2014) |

|---|---|

| 9,147 | |

| 3,409 | |

| 1,763 | |

| 1,246 | |

| 1,198 | |

| 1,101 | |

| 962 | |

| 921 | |

| 887 | |

| 802 | |

Places of interest

Architecture

- Bochum City Hall was built from 1927–1931 and was designed by architect Karl Roth as a modern office building, but in the Renaissance style, reflecting the industrial era's middle class, inventions and discoveries. There were statues of bronze and stone, and in the city council chambers, a bell tower. The ornate décor gave the Nazis an excuse to hound the then-mayor, who was of Jewish descent, driving him to suicide in 1933. Most of the bronze statues were melted down for the war effort and the stone carvings were damaged by the war, save for some small lion's heads over the entrance. Also left undamaged are two themed courtyard fountains made by August Vogel, the "Fountain of Beauty" and the "Fountain of Happiness", as well as Augusto Vasaris' florentine main entrance, which displays the motto, In Labore Honos (In labour lies honour). In 1951, a set of 28 chimes was installed, manufactured in Bochum. Known for their clarity of tone, they are the first cast steel chimes in the world.[25] In front of the city hall is a large bell that was made by the Bochum "Verein für Bergbau und Gusstahlfabrikation AG", (Association for Mining and Cast Steel Manufacturing). Displayed at the 1867 Paris World's Fair, it has a diameter of 3.13 metres (10.27 ft) and weighs 15,000 kg (16.53 US tonnes). It was damaged during World War II and can no longer be rung.

- Altes Brauhaus Rietkötter, the Old Rietkötter Brewing House is one of the oldest houses in Bochum, dating from 1630. Originally a private home, it became a brewery in 1777. After nearly being torn down after the war, it now has preservation status and today houses a restaurant, where they still brew their own beer.[26]

- The Kaufhaus Kortum department store dates from 1913 and was built as one of the nearly 20 regional stores owned by Alsberg Bros. (Gebr. Alsberg, AG) of Cologne. During the Nazi era, these stores were taken away from their Jewish owners and put into non-Jewish hands. Today, the "Kaufhaus Kortum" building has preservation status and houses an electronics store.

- The Friedrich Lueg Haus was built in 1924-1925 as the first high-rise building in Bochum. Contracted by the Lueg Company, the seven-story building was designed by the architect Emil Pohle. It suffered a fire during a bombing raid in 1944 and was renovated after the war. Today, the upper floors are small offices and internet companies. The seven-theatre Bochum Union Cinema rents the ground floor, showing a variety of domestic and international films.[27]

- Mutter Wittig is a baroque-style building in the town centre, originally opened as a bakery and inn in 1870. Damaged in World War II, its façade is protected by preservation status. It houses a restaurant and its windows are decorated with displays of old Bochum.[28]

- Sparkasse Bochum (Bochum Savings Bank) is a town landmark designed by the architect Wilhelm Kreis. It opened in 1928 and was emblematic of the modern era. It was heavily damaged during the war, but was afterwards restored to its former appearance.

- The Schlegel Tower is the only remaining structure of the once-important Schlegel brewery, which closed in 1980.

- The Jahrhunderthalle (Hall of the Century), is the former gas and power station of a steel mill built at the turn of the 20th century. With the closing of the mill, the plant was renovated and turned into a three-hall concert and event site with an industrial ambiance.[29][30]

- Dahlhauser Heide is an example of social welfare provided by wealthy German industrialists for their workers. Built in the early 1900s by the Krupp family for their coal mine workers, the modest and tastefully designed two-family houses were to enable self-sufficiency by providing gardens and a stall for a cow. The estate, which has the appearance of a small, rural town, gained preservation status in the 1970s.[31][32]

- Blankenstein Castle was built in the 13th century by Count Adolf I of the Mark. Though located in Hattingen, it is owned by Bochum and has a significant history. On 8 June 1321, Count Engelbert II of the Mark granted Bochum its town charter there. Today, only the gate and one tower remain.[33]

- Haus Kemnade is a moated castle. Though located in the town of Hattingen, the castle is property of the city of Bochum in 1921. Documents regarding its earliest dates of construction have been lost; it is first mentioned in 1393. Parts of the castle were built during the Renaissance and baroque periods. The castle's location on the banks of the Ruhr river was changed when the flood of 1486 receded on the opposite side, cutting the castle off from the neighbouring village. The castle remained in private hands till 1921, when it was deeded to the city of Bochum. In 1961, a museum of local history was installed, including a large collection of 16th to 20th century musical instruments. A collection of East Asian objects is also now located there, as well as a satellite of the Bochum Museum and an art exhibition space. There is also a restaurant on site. Behind the castle is a timber-framed farmhouse from 1800, now a museum exhibiting farm life from the past.[34]

Religious architecture

- Propsteikirche St. Peter und Paul, is the oldest church in Bochum, built between 785-800 by Charlemagne. It was rebuilt in the 11th century, but was severely damaged by fire in 1517. In 1547, it was again rebuilt, this time in the late Gothic style. The 68-metre (223 ft) high bell tower is one of the landmarks of Bochum. The interior includes a baptismal font from 1175, the reliquary shrine of St. Perpetua and her slave Felicitas, and a high altar with a crucifix from 1352.

- Pauluskirche, is the main Protestant church of the city. After the Reformation, both Catholics and Lutherans shared the Propsteikirche, often contentiously. In 1655, the Lutherans began to build their own church with the help of donations from the Dutch Republic, Sweden, Courland and Denmark. The church was heavily damaged in a bombing raid on 12 June 1943 and was later rebuilt after the war. Next to the church is a monument to peace. A statue of an old woman searching for a loved one, it is also a memorial to the 4 November 1944 bombing raid on Bochum. Hans Ehrenberg served as minister here, until he was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen by the Nazis.[35]

- The Christuskirche, built in the neo-Gothic style, opened in 1879 and was among the most beautiful churches in Europe. In 1931, the room in the steeple was extended to a cenotaph for those killed in World War I. During an air raid in 1943, the church was destroyed, except for the steeple. After the war, the ruins were integrated into a new, modern structure and the steeple became a memorial dedicated to peace and understanding among nations.

- The neo-Gothic Marienkirche, built between 1868–1872, was heavily damaged in World War II (see photo above), but was rebuilt after the war. It is now closed and scheduled for demolition. The stained glass windows have been removed and it has fallen victim to vandalism.

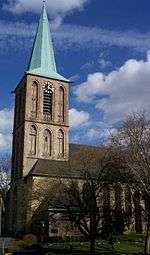

- Stiepeler Dorfkirche is over 1000 years old and was commemorated by a stamp in 2008. A small church consisting of one room was built by Countess Imma von Stiepel. Between 1130 and 1170, the old church was replaced by a Romanesque basilica. Today, the steeple and transept remain. Between 1150 and 1200, the interior walls and ceiling were decorated with a number of Romanesque paintings.

- The new synagogue, which opened in 2007, consists of a white cube and stands in contrast to the round shape of the planetarium next door. The façade shows overall a variation on the Solomon's Seal achieved by relocated brickstones. The interior is graced with a gold-coloured canopy.

Parks and Gardens

Bochum has a municipal zoo, a large municipal park and a number of other gardens and parks. The Ruhr University Botanical Gardens has thousands of plants from all over the world.[36] Among others there is a tropical garden, a cactus garden, and a Chinese garden designed in the southern Chinese style, the only one of its kind in Germany.

The Geological Garden was the first of its kind in Germany. The nearly 4-acre (16,000 m2) park is the site of an old coal mine, the Zeche Friederika, which operated from 1750 to 1907. In 1962, the property came under environmental protection and a decade later was turned into a geological garden.[37]

Other scenic areas include the West Park, Lake Kemnade, Lake Ümmingen and the municipal forest, Weitmarer Holz.[38]

Society and Culture

Leisure and Entertainment

Bochum is a cultural centre of the Ruhr region. There is a municipal theatre, the Schauspielhaus Bochum, and about 20 smaller theatres and stages. The musical Starlight Express, which opened in 1988, is the longest-running musical in Germany.[39]

Bermudadreieck

The Bermudadreieck (Bermuda Triangle), in the city center of Bochum, functions as the town's nightlife hub. Around sixty different bars and restaurants are located there, serving multicultural cuisine such as Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Italian, Spanish and German gastronomic specialties.

Annual Events

- Jumble Sale – on the third Saturday of the month, in front of city hall

- April/May: Maiabendfest – local festival, hundreds of years old

- May: Steam Festival (every other year)

- June events:

- Rubissimo, Ruhr University's summer festival

- Kemnade International

- Extraschicht - Night of Industrial Heritage (many locations all over the Ruhr area)

- June/July: VfL for Fun – summer festival for Bochum's football (soccer) team, VfL Bochum 1848

- July: Bochum Total (Rock Music Festival) - starts on the first weekend after school lets out

- July or August: Bochum kulinarisch – culinary treats from various cuisines, held the last weekend of summer vacation

- August: Bochumer Musiksommer, Bochum's Summer of Music

- September: Open Flair - international cabaret and street theatre

- October: Oktobermarkt – October Market

- October/November: Bochumer Bachtage - music of composer Johann Sebastian Bach

- October/November: Ruhrgebiets-Antiquariatstag - used and antique book sale

- November: Children's and Teenagers' Theatre

- December: Weihnachtsmarkt – Christmas Market - month-long open air market spread over the heart of downtown Bochum, includes performance stages

Museums

- The Bergbaumuseum is a museum about mining technology, complete with pithead tower.

- Railway Museum and Station Dahlhausen in the borough of Dahlhausen. Dr.-C.-Otto-Straße 191

- Zeiss Planetarium

- At the city's border with Herne-(Röhlinghausen), is the former mine Zeche Hannover with the Malakow Tower and engine hall. There is a steam-powered winding engine, which is operated at events.

- Zeche Knirps ("Small Boy Mine") located on the ground of Mine Hannover. It gives children the opportunity to experience the processes in a mine.

- Museum of local history Helf's Farm, Address: In den Höfen 37

- Farmhouse Museum located on the grounds of moated Kemnade Castle

- Museum of historic medical tools in the Malokos-Tower of former Mine Julius-Philipp from 1875. Address: Malakowturm, Markstraße 258a, 44799 Bochum

- School Museum, Cruismannstraße 2, 44807 Bochum

- Telefonmuseum, Karl-Lange-Str. 17

Art galleries

- Museum of Art The collection's focus is central and eastern European avant garde art, German expressionism, surrealism and outsider art. Kortumstraße 147, Bochum

- Ruhr University art collection Modern art meets the classical. Marble and bronze portraits of Greek and Roman emperors, collection of antique Greek vases from the 9th to 4th century, B.C. Universitätsstraße 150, Bochum

- Schlieker House In the former apartment and studio of German painter Hans-Jürgen Schlieker (1924–2004); changing exhibitions. Hours: Wed. & Sun. 3:00 - 6:00 pm. Paracelsusweg 16, 44801 Bochum

- Situation Kunst (Situation Art) Located at "Haus Weitmar" park. Indoor permanent exhibition with works by Gianni Colombo, Dan Flavin, Gotthard Graupner, Norbert Kricke, Lee Ufan, François Morellet, Maria Nordman, David Rabinowitch, Arnulf Rainer, Dirk Reinartz, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Ryman, Richard Serra, Jan J. Schoonhoven; also the Africa and Asia Room. Hours: Wed 2:00-6:00 pm, Fri 2:00-6:00 pm, Sat 12:00-6:00 pm, Sun 12:00-6:00 pm. Nevelstraße 29c, 44795 Bochum. Tel.: +49 (0)234-298-8901, Fax: +49 (0)234-298-8902

- Musical Instrument Collection, Hans and Hede Grumbt. Large collection of musical instruments, also the clarinet collection of Johan van Kalker. An der Kemnade 10, 45527 Hattingen, Tel.: +49 (0)2324-302-68

- Ostasiatika Collection Ehrich. Kurt Ehrich's east Asian collection of Japanese netsuke, belt buckles, a display of the seven "lucky gods" and other additional objects. An der Kemnade 10, 45527 Hattingen, Tel: (0)2324-302-68

- ER MindArts Contemporary Art online Gallery was established in Bochum in 2014. www.ermindarts.com

Art in public spaces

- Richard Serra's sculpture, "Terminal" is located in the town centre, near the central station. It consists of four 12-metre (over 39 feet) tall steel plates.

- Ulrich Rückriem's sculpture, "Ohne Titel" (titled "Untitled"), is at the intersection of Kortumstrasse and Huestrasse. (It is currently in storage because of construction.)

- Memorial of the herdsman at Massenberg-Boulevard: shown is the historical person "Fritz Kortebusch", the last herdsman of the town. In 1870 he guided the cattle of the citizens for the last time to the "Vöde", a grassland outside the town limits, which is today the municipal park.

- Engelbert fountain at Kortumstrasse, in memory of Earl Engelbert II, who granted a town charter to Bochum in 1321-1324.

- Jobsiade-fountain at Husemann-Square. Shown is a scene of the examination of Hieronymus Jobs, the main character of the "Jobsiade", a comical poem of the poet Carl Armold Kortum.

- "The envolvement of the City", sculpture of Professor Karl Henning Seemann at Schützenbahn street.

- Collection of sculptures inside the municipal park.

- The bell in front of the city hall serves as a reminder of the improvement of steel-casting in Bochum. The bell was built in 1867 for the Paris World's Fair.

- Stolpersteine, (literally, "stumbling stones") are small, cobblestone-sized, brass commemorative plaques which are set in sidewalks all over Europe, marking the homes or work places of Jews and others who were arrested and murdered during the Nazi era. There are 38 stolpersteine in Bochum.[40]

- Cenotaph for the victims of the mine disaster at "Vereinigte Präsident" in 1936. The sculpture was created by Wilhelm Wulff. Strict guidelines for artwork were in effect during the Nazi dictatorship, yet the sculpture follows only a few of them. The inscription also avoids typical Nazi phraseology.

Sports

- The football club VfL Bochum played in the first Division from 1971–1992, and from 1992–2010 was alternating almost every year between first and second Division, but mostly first. Since 2010 it has played in the second Division (2. Bundesliga).

- Sparkassen Giro Bochum - annual road bike race.

Located companies

- Sparkasse Bochum - public-law bank

- Bogestra (Hauptsitz) - Bochum-Gelsenkirchener Straßenbahnen AG, local traffic firm

- Deutsche Annington Immobilien GmbH – Germany's largest real estate company (headquarters)

- Gebr. Eickhoff Maschinenfabrik u. Eisengießerei GmbH

- Privatbrauerei Moritz Fiege, middle-large regional beer brewery

- GEA Group AG (headquarters) – high-tech ventilation systems and machines, the largest publicly traded company in Bochum

- Johnson Controls, just-in-time industry supplier for parts of the car, especially for Opel

- United Cinemas International

- Roeser Medical

- Adam Opel AG – In Bochum's factories are among others the Opel Zafira and the Opel Astra Caravan and the five-door car are produced

- GLS Bank

- ThyssenKrupp

- Bochumer Verein – former part of the enterprise ThyssenKrupp

- QVC – call centre

- FABER Lotto-Service KG

- USB Umweltservice Bochum GmbH – municipal disposal firm (100% subsidiary of the Bochumer Stadtwerke)

- ARAL AG (Hauptsitz), an enterprise of the Deutsche BP AG

- Bochumer Eisenhütte Heintzmann GmbH & Co. KG – Mining, tunnelling and heat treatment

- Wollschläger Group (Hauptsitz) – trading house in the sector tooling equipment and machines

- Meteomedia GmbH (Hauptsitz) – private weather service, German subsidiary of the Swiss Meteomedia ag

- G DATA Software AG (Unternehmenssitz) – contractor of IT security solutions. well-known product: G DATA AntiVirus

- Möbel Hardeck – furniture shop

- Dr. C. Otto & Comp. – fire-proof materials

- VMRay GmbH – CyberSecurity

Transport

Roads

Bochum is connected to the Autobahn network by the A 40, A 43 and A 44 autobahns. In addition, Bochum has a ring road, built to expressway standards, consisting of four segments; the Donezk, Oviedo, Nordhausen and Sheffield-Ring roads. It serves as a three-quarter loop around central Bochum and begins and ends at Autobahn A40. Ruhr University Bochum is also served by an expressway running from the Nordhausen-Ring to Autobahn A43. Until 2012, a new interchange (Dreieck Bochum-West) between the Donezk-Ring and Autobahn A40 is being constructed within tight parameters due to the existence of a nearby factory.

Apart from the autobahns and expressways, there is also a small ring road around the centre of Bochum, where most roads radiating out of Bochum begin. Most main roads in Bochum are multi-lane roads with traffic lights. Bochum is also served by the Bundesstraße 51 and Bundesstraße 226. B51 runs to Herne and Hattingen, and B226 runs to Gelsenkirchen and Witten.

Railways

Bochum has a central station situated on the line from Duisburg to Dortmund, connecting the city to the long-distance network of Deutsche Bahn as well as to the Rhine-Ruhr S-Bahn network.

Bus, Tram, Underground

Local service is supplied mainly by BOGESTRA, a joint venture handling transportation between the cities of Bochum and Gelsenkirchen. The Bochum Stadtbahn is a single underground line connecting the University of Bochum to Herne, and the Bochum/Gelsenkirchen tramway network is made up of several lines, partially underground, connecting to Gelsenkirchen, Hattingen and Witten. Public transport in the city is priced according to the fare system of the VRR transport association.

Waterways

As one of the few Ruhr area cities, Bochum is not directly connected with the German waterway net; the closest link is in the more northern located Herne at the Rhine-Herne Canal. In the south the border of Bochum is marked by the Ruhr. Up to the first half of the 19th century it was one of the most-travelled rivers in Europe and was mainly used for coal departure. Despite of tour ships, the navigation time ended long ago.

Air

The closest airports are Essen/Mülheim Airport (27 km), Dortmund Airport (31 km) and Düsseldorf International Airport (47 km). To reach the airport in Düsseldorf, there are ICE, InterCity, RE and S railway lines. Other reachable airports are the Cologne Bonn Airport, the Weeze Airport, the Münster Osnabrück International Airport and the Paderborn Lippstadt Airport.

Education

Higher education

- Ruhr University Bochum, founded 1965

- Bochum University of Applied Sciences (Hochschule Bochum, formerly Fachhochschule Bochum)

- Georg Agricola University of Applied Sciences (TFH Georg Agricola)

- Protestant University of Applied Sciences, Rheinland-Westphalia-Lippe (Evangelische FH Rheinland-Westfalen-Lippe)

- Bochum Acting School (Schauspielschule Bochum)

- College of the Federal Social Security, Department of Social Insurance for Seafarers (Fachhochschule des Bundes der Sozialversicherung, Abteilung Knappschaft-Bahn-See)

- University of Health Sciences (Hochschule für Gesundheit)

Elementary and secondary schools

There are 61 primary schools, 9 Hauptschulen ("general schools") and 14 special schools.

In addition, there are 11 preparatory (British: grammar) schools ("Gymnasien"), 5 comprehensive schools ("Gesamtschulen"), 8 Realschulen and 2 private Waldorf schools.

"Gymnasien" – preparatory schools (British: grammar school):

- Goethe-Schule Bochum

- Graf-Engelbert-Schule

- Heinrich-von-Kleist-Schule

- Hellweg-Schule

- Hildegardis-Schule

- Lessing-Schule

- Märkische Schule

- Neues Gymnasium Bochum (school formed by merger of the former Albert-Einstein-Schule and Gymnasium am Ostring)

- Schiller-Schule

- Theodor-Körner-Schule

"Gesamtschulen" – comprehensive schools:

- Erich Kästner-Gesamtschule Schule

- Heinrich-Böll-Gesamtschule

- Maria Sibylla Merian-Gesamtschule

- Willy-Brandt-Gesamtschule

- Matthias-Claudius-Schulen

Realschulen – high schools:

- Anne-Frank-Schule

- Annette-von-Droste-Hülshoff-Schule

- Franz-Dinnendahl-Schule

- Hans-Böckler-Schule

- Helene-Lange-Schule

- Hugo-Schultz-Schule

- Pestalozzi-Schule

- Realschule Höntrop

- Freie-Schule Bochum (with elementary school)

- Rudolf Steiner Schule Bochum

- Widar Schule Wattenscheid

Twin towns (sister cities)

Bochum's twin towns are:

-

Sheffield, United Kingdom, since 1950

Sheffield, United Kingdom, since 1950 -

Oviedo, Spain, since 1980

Oviedo, Spain, since 1980 -

Donetsk, Ukraine, since 1987

Donetsk, Ukraine, since 1987 -

Nordhausen, Germany, since 1990

Nordhausen, Germany, since 1990 -

Xuzhou, People's Republic of China, since 1994

Xuzhou, People's Republic of China, since 1994 -

Ivybridge, United Kingdom

Ivybridge, United Kingdom -

Kashan, Iran since 1994

Kashan, Iran since 1994

Notable residents

- Wolfgang Clement (b. 1940), former Minister of Economy and Labour

- Hans Ehrenberg (1883–1958), theologian, Nazi critic, and co-founder of the Confessing Church

- Manfred Eigen (b. 1927), 1967 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry

- Tommy Finke (b. 1981), songwriter and composer

- Frank Goosen (b. 1966), cabaret artist and author, wrote Learning to Lie

- Herbert Grönemeyer (b. 1956), actor (Das Boot), singer, songwriter, who became famous with the song "Bochum"

- Claus Holm (1918–1996), actor, born in Bochum

- Else Hirsch (1889–1943), Jewish teacher who organised 10 Kindertransports to England and the Netherlands

- Alfred Keller (1882–1974), general in the Luftwaffe during the Second World War

- Thomas Köner (b. 1965), multimedia artist

- Norbert Lammert (b. 1948), president (Speaker) of the Bundestag (German parliament)

- Dorothee Mields (b. 1971), soprano soloist, leading interpreter of 17th and 18th Century music

- Andrei Osterman (1686–1747), Bochum-born Russian statesman

- Konrad Raiser (b. 1938), former General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, taught theology in Bochum

- Otto Schily (b. 1932), former Minister of the Interior

- Hans-Jürgen Schlieker (1924–2004), painter

- André Tanneberger (b. 1973), also known as "ATB", electronic music producer, began his career in Wattenscheid

- Mark Warnecke (b. 1970), breaststroke swimmer, won the world title at the age of 35

References

- ↑ "Amtliche Bevölkerungszahlen". Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW (in German). 23 September 2015.

- ↑ Webpage Ruhrverband with technical data

- ↑ emscher:dialog in Bochum, planning process document, published by Emschergenossenschaft, April 16th 2002

- ↑ Nelson D. Schwartz. "Europe Feels the Strain of Protecting Workers and Plants" New York Times 25 May 2009. Accessed 1 March 2010

- ↑ "Opel sees no alternative to closing Bochum". Reuters. 10 December 2012.

- ↑ "Nokia to close Bochum, Germany plant" boston.com, 15 January 2008. Accessed 1 March 2010

- ↑ "Anger at Nokia swells in Germany; top politicians join fray over plant closure" Helsingin Sanomat International Edition. 21 January 2008. Accessed 1 March 2010

- ↑ Press release Germany Trade & Invest, 23 April 2008. Accessed 1 March 2010

- ↑ "Blackberry maker RIM to set up R&D site in Bochum, add 300 jobs - report" Forbes Magazine, 14 April 2008. Accessed 1 March 2010

- ↑ "Blackberry Bold 9700 launch" Government of Canada official website. 17 November 2009. Accessed 1 March 2010

- ↑ Karin Finkbohner, Betti Helbing, Carola Horn, Anita Krämer, Astrid Schmidt-Ritter, Kathy Vowe. Wider das Vergessen — Widerstand und Verfolgung Bochumer Frauen und Zwangsarbeiterinnen 1933–1945 pp. 62-63. Europäischer Universitätsverlag, ISBN 978-3-932329-62-3 (German)

- ↑ "The Final Operation – Bochum" 57 Squadron. Accessed 8 March 2010

- ↑ "Geschichte: Gottesfurcht Vaterland" Christuskirche Bochum. Retrieved 23 January 2011 (German)

- ↑ Chronology Official web site, Bochumer Verein. Accessed 7 March 2010

- 1 2 70 000 Obdachlose in Bochums Zentrum History of Bochum, World War II. "70,000 homeless in downtown Bochum" (4 November 1944) Accessed 7 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Aerial photo of Bochum, showing bombed steel plant Australian War Memorial. Accessed 30 April 2015

- ↑ "Zahl der Kriegs- und NS-Opfer nicht mehr feststellbar" History of Bochum, World War II. (1 July 1945) "Number of war and Nazi victims no longer ascertainable" Accessed 8 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ "Menschen kehren zurück in zerstörte Städte" History of Bochum, World War II. "People return to destroyed cities" (May 5, 1945) Accessed 8 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ History of Bochum, World War II. "Main offensive on Bochum." Accessed 7 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939-1946 (Revised Edition, 2006), Stackpole Books, p. 148.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel. Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, Band 3 (Site of Terror: The History of Nazi Concentration Camps, Volume 3) p. 395 (2006) ISBN 978-3-406-52963-4 (German)

- ↑ "10-Zentner Bombe gefunden" History of Bochum, World War II. "1000 pound bomb found." Accessed March 8, 2010 (German)

- ↑ "WWII bomb injures 17 at Hattingen construction site" The Local, German news in English. 19 September 2008. Accessed March 8, 2010

- ↑ "Ausländer und Staatenlose 2010 bis 2014 in Bochum". Stadt Bochum. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- ↑ City Hall "Historischer Rundgang Bochum - Rathaus". Accessed 4 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Altes Brauhaus Rietkötter Official website. Accessed 4 March 2010

- ↑ Union Filmtheater Bochum Official website. Accessed 4 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ "Mutter Wittig" "Historischer Rundgang Bochum - Mutter Wittig". Accessed 4 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Ruhr Tourism website "Jahrhunderthalle". Accessed 4 March 2010

- ↑ Jahrhunderthalle Bochum Official website. Accessed 4 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Eugene C. McCreary. "Social Welfare and Business: The Krupp Welfare Program, 1860-1914". The Business History Review, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring, 1968), pp. 24-49

- ↑ Bergarbeitersiedlung Dahlhauser Heide Ruhr Guide to Dahlhauser Heide. Accessed 4 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ "Burg Blankenstein" www.ruhr-guide.de - DAS Online-Magazin für das Ruhrgebiet. Accessed 2 March 2010. (German)

- ↑ Wasserburg Haus Kemnade Official website. Accessed 4 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ "Station 12: Christuskirche" Stadt Bochum (City of Bochum), official website. Retrieved 2 April 2011 (German)

- ↑ Ruhr University Botanical Gardens Alphabetical list of plants, with photos. Accessed 8 March 2010.

- ↑ Bochum Geological Garden City of Bochum website. Accessed 8 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Schöne Plätze und erholsame Orte City of Bochum website. (Beautiful and relaxing spots.) Accessed 8 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ Article about number of visitors Starlight Express website. Accessed 8 March 2010 (German)

- ↑ List of stolperstein locations in Bochum, with photos German genealogy wiki website. Retrieved 1 May 2010 (German)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bochum. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bochum. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|