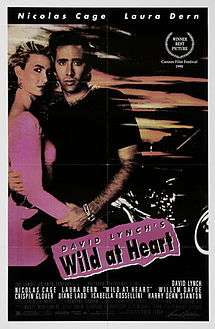

Wild at Heart (film)

| Wild at Heart | |

|---|---|

|

Theatrical release poster | |

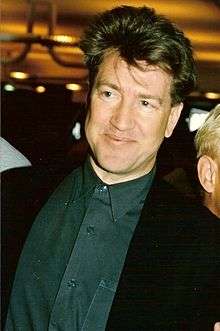

| Directed by | David Lynch |

| Produced by |

Steve Golin Monty Montgomery Sigurjon Sighvatsson |

| Screenplay by | David Lynch |

| Based on |

Wild at Heart by Barry Gifford |

| Starring |

Nicolas Cage Laura Dern Willem Dafoe Crispin Glover Diane Ladd Isabella Rossellini Harry Dean Stanton |

| Music by | Angelo Badalamenti |

| Cinematography | Frederick Elmes |

| Edited by | Duwayne Dunham |

| Distributed by | The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[1] |

| Box office | $14,560,247[2] |

Wild at Heart is a 1990 American crime thriller film written and directed by David Lynch, and based on Barry Gifford's 1989 novel of the same name. Both the book and the film revolve around Sailor Ripley and Lula Pace Fortune, a young couple from Cape Fear, North Carolina who go on the run from her domineering mother. Due to her mother's machinations, the mob becomes involved.

Lynch was originally going to produce, but after reading Gifford's book decided to also write and direct the film. He did not like the ending of the novel and decided to change it in order to fit his vision of the main characters. Wild at Heart is a road movie and includes several allusions to The Wizard of Oz as well as Elvis Presley and his movies.[3]

Early test screenings for the film did not go well; Lynch estimated that 80 people walked out of the first test screening and 100 in the next. At the time of its release, the film received mixed critical reviews and was a moderate success at the US box office, grossing USD$14 million, above its $10 million budget. The film won the Palme d'Or at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival,[4] at which it received both negative and positive attention from its audience. Diane Ladd was nominated for Best Supporting Actress for both the Academy Awards and the Golden Globes. It has since received some positive re-evaluation from critics.

Plot

Lovers Lula and Sailor are separated after he is jailed for killing a man who attacked him with a knife; the assailant, Bobby Ray Lemon, was hired by Lula's mother, Marietta Fortune. Upon Sailor's release, Lula picks him up at the prison where she hands him his snakeskin jacket. They go to a hotel where she reserved a room, make love and go to see the speed metal band Powermad. At the club, Sailor gets into a fight with a man who flirts with Lula, and then leads the band in a rendition of Elvis Presley's "Love Me". Later, back in the room, after making love again, Sailor and Lula finally decide to run away to California, breaking Sailor's parole. Marietta arranges for private detective Johnnie Farragut – her on-off boyfriend – to find them and bring them back. Unbeknownst to Farragut, however, Marietta also hires gangster Marcellus Santos to track them, and kill Sailor. Santos's minions capture and kill Farragut, sending Marietta into a guilt-fueled psychosis.

Unaware of all of the events happening back in North Carolina, Lula and Sailor continue on their way until – according to Lula – they witness a bad omen: the aftermath of a two-car accident, and the only survivor, a young woman, dies in front of them. With little money left, Sailor heads for Big Tuna, Texas, where he contacts "old friend" Perdita Durango, who might be able to help them, although she secretly knows he is under contract to be killed by Lula's mother. Inevitably, while Sailor agrees to join up with gangster Bobby Peru in a feed store robbery, Lula waits for him in the hotel room, trying to conceal that she is pregnant with Sailor's child. While Sailor is out Bobby enters the room, and forces Lula to implore him to make love with her, but in the end he refuses, stating he has no time.

The robbery goes spectacularly wrong when Peru unnecessarily shoots the two clerks. Peru then admits to Sailor he's been hired to kill him and Sailor realizes he has been given a pistol with dummy ammunition. Chasing Sailor out of the store, Peru is about to kill him when the sheriff's deputy opens fire on him and Peru accidentally blows his own head off with his own shotgun. Sailor is arrested and sentenced to six years in prison.

While Sailor is in jail, Lula has their child. Upon his release Lula decides to reunite with him. Rejecting her mother's objections over the phone, she throws water over her mother's photograph and goes to pick up Sailor with their son. When they meet Sailor, he reveals he will be leaving them both, having decided while in prison that he isn't good enough for them. While he is walking a short distance away, Sailor encounters a gang who surround him. He insults them and they quickly knock him out. While unconscious, he sees a vision in the form of Glinda the Good Witch, who tells him, "Don't turn away from love, Sailor". When he awakens, he apologizes to the men, tells them he realizes the error of his ways, then runs after Lula. The photograph of Marietta in Lula's house sizzles and vanishes. As there is a traffic jam on the road, Sailor begins to run over the roofs and hoods of the cars to get back to Lula and their child in the car. Sailor sings "Love Me Tender" to Lula, having earlier said that he would only sing that song to his wife.

Cast

- Nicolas Cage as Sailor Ripley: The actor described his character as "a kind of romantic Southern outlaw".[5] Cage said in an interview that he was "always attracted to those passionate, almost unbridled romantic characters, and Sailor had that more than any other role I'd played".[5] Previous to being cast in the film, he had met Lynch several times at Hollywood eatery Musso & Frank Grill that they both frequented. When Lynch read Gifford's novel, he immediately wanted Cage to play Sailor.[6]

- Laura Dern as Lula Pace Fortune: Dern had starred in a supporting role in Lynch's previous film, Blue Velvet. For Dern, this was the first opportunity she had "to play not only a very sexual person, but also someone who also was, in her own way, incredibly comfortable with herself".[5] When Lynch read Gifford's novel, he immediately thought of Dern to play Lula.[7]

- Diane Ladd as Marietta Fortune, Lula's overbearing mother, who forbids Lula and Sailor's relationship; she forms a grudge against Sailor after he rejects her advances. Ladd and Dern are mother and daughter in real life.[8]

- Harry Dean Stanton as Johnnie Farragut, a private detective and Marietta's boyfriend. This marks the first of multiple collaborations between Stanton and Lynch.

- J. E. Freeman as Marcellus Santos, a gangster and Marietta's other boyfriend.

- W. Morgan Sheppard as Mr. Reindeer, a mysterious crime boss in league with Santos.

- Willem Dafoe as Bobby Peru, a criminal hired by Mr. Reindeer to kill Sailor.

- Crispin Glover as Dell, Lula's mentally ill cousin who puts cockroaches in his underwear and has an unnatural obsession with Christmas.

- Grace Zabriskie as Juana Durango, a criminal who works with Mr. Reindeer.

- Isabella Rossellini as Perdita Durango, a criminal who once worked with Sailor and is now partners with Bobby Peru. Later the protagonist in the spinoff film Perdita Durango.

- Sherilyn Fenn as Girl in car accident. Lynch based her off of an image of a broken China doll.

- Sheryl Lee as the Good Witch, who appears to Sailor in a vision, telling him not to give up on love.

- David Patrick Kelly as Dropshadow, a hitman who wears the same military tattoo as Bobby Peru.

- Pruitt Taylor Vince as Buddy, a Big Tuna local in a cowboy hat staying at the same motel as Sailor and Lula.

- Jack Nance as 00 Spool, a crazy rocket scientist Sailor and Lula meet at the motel.

- John Lurie as Sparky, one of Bobby Peru's associates.

- Darrell Zwerling as Singer's manager

- Glenn Walker Harris, Jr. as Pace, the son of Sailor and Lula

Production

In the summer of 1989, Lynch had finished the pilot episode for the successful Twin Peaks television series and tried to rescue two of his projects – Ronnie Rocket and One Saliva Bubble – both involved in contractual complications as a result of Dino De Laurentiis' bankruptcy, which had been bought by Carolco Pictures.[1][9] Lynch stated, "I've had a bad time with obstacles . . . It wasn't Dino's fault, but when his company went down the tubes, I got swallowed up in that".[1] Independent production company Propaganda Films commissioned Lynch to develop an updated noir screenplay based on a 1940s crime novel while Monty Montgomery, a friend of Lynch's and an associate producer on Twin Peaks, asked novelist Barry Gifford what he was working on.[9] Gifford happened to be writing the manuscript for Wild at Heart: The Story of Sailor and Lula but still had two more chapters to write.[10] He let Montgomery read it while the producer was working on the pilot episode for Twin Peaks in pre-published galley form. Montgomery read it and two days later called Gifford and told him that he wanted to make a film of it.[10] Two days afterwards, Montgomery gave Lynch Gifford’s book while he was editing the pilot, asking him if he would executive produce a film adaptation that he would direct.[11] Lynch remembers telling him, "That’s great Monty, but what if I read it and fall in love with it and want to do it myself?"[9] Montgomery did not think that Lynch would like the book because he did not think it was his "kind of thing."[11] Lynch loved the book and called Gifford soon afterwards, asking him if he could make a film of it.[10] Lynch remembers, "It was just exactly the right thing at the right time. The book and the violence in America merged in my mind and many different things happened."[9] Lynch was drawn to what he saw as "a really modern romance in a violent world – a picture about finding love in hell," and was also attracted to "a certain amount of fear in the picture, as well as things to dream about. So it seems truthful in some way."[9]

Lynch got approval from Propaganda to switch projects; however, production was scheduled to begin two months after the rights had been purchased, forcing the director to work fast.[12] He had Cage and Dern read Gifford's book[5] and wrote a draft in a week.[1][11] By Lynch's own admission, his first draft was "depressing and pretty much devoid of happiness, and no one wanted to make it".[13] Lynch did not like the ending in Gifford’s book where Sailor and Lula split up for good. For Lynch, "it honestly didn’t seem real, considering the way they felt about each other. It didn’t seem one bit real! It had a certain coolness, but I couldn’t see it".[9] It was at this point that the director's love of The Wizard of Oz (1939) began to influence the script he was writing and he included a reference to the "yellow brick road".[14] Lynch remembers, "It was an awful tough world and there was something about Sailor being a rebel. But a rebel with a dream of the Wizard of Oz is kinda like a beautiful thing".[14] Samuel Goldwyn, Jr. read an early draft of the screenplay and did not like Gifford’s ending either, so Lynch changed it. However, the director was worried that this change made the film too commercial, "much more commercial to make a happy ending yet, if I had not changed it, so that people wouldn’t say I was trying to be commercial, I would have been untrue to what the material was saying".[9]

Lynch also added new characters, like Mr. Reindeer and Sherilyn Fenn as the victim of a car accident.[15] During rehearsals, Lynch began talking about Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe with Cage and Dern.[16] The director acquired a copy of Elvis' Golden Records and after listening to it, called Cage and told him that he had to sing two songs, "Love Me" and "Love Me Tender". The actor agreed and recorded them so that he could lip-synch to them on the set. At one point, Cage called Lynch and asked if he could wear a snakeskin jacket in the film and Lynch incorporated it into his script.[16] Before filming started, Dern suggested that she and Cage go on a weekend road trip to Las Vegas in order to bond and get a handle on their characters.[11] Dern remembers, "We agreed that Sailor and Lula needed to be one person, one character, and we would each share it. I got the sexual, wild, Marilyn, gum-chewing fantasy, female side; Nick’s got the snakeskin, Elvis, raw, combustible, masculine side".[8] Within four months, Lynch began filming on August 9, 1989 in both Los Angeles (including the San Fernando Valley) and New Orleans with a relatively modest budget of $10 million.[1] Originally, the film featured more explicit erotic scenes between Sailor and Lula. In one, she has an orgasm while relating to Sailor a dream she had of being ripped open by a wild animal. Another deleted scene had Lula lowering herself onto Sailor's face saying, "Take a bite out of Lula".[7]

Themes

One of the film's themes is, according to Lynch, "finding love in Hell". He has stated "For me, it's just a compilation of ideas that come along. The darker ones and the lighter ones, the humorous ones, all working together. You try to be as true as you can to those ideas and try to get them on film."[1] Some critics have postulated that, similar to Lynch's previous Blue Velvet, the sudden idealistic ending of perfect happiness is ironic, suggesting that people who have the potential for violence struggle to find true happiness.[17] Lynch himself, however, refers to the ending of Wild at Heart as being a "happy" one, having consciously made the decision to change the original darker ending from the novel.[9]

Release

Distribution

Early test screenings for Wild at Heart did not go well, with the strong violence in some scenes being too much. At the first test screening, eighty people walked out during a graphic torture scene involving Johnnie Farragut.[13] Lynch decided not to cut anything from the film and at the second screening one hundred people walked out during this scene. Lynch remembers, "By then, I knew the scene was killing the film. So I cut it to the degree that it was powerful but didn't send people running from the theatre".[13] In retrospect, the filmmaker said, "But that was part of what Wild at Heart was about: really insane and sick and twisted stuff going on."[9]

The film was completed one day before it debuted at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival in the 2,400-seat Grand Auditorium. After the screening, it received "wild cheering" from the audience.[18] When Jury President Bernardo Bertolucci announced Wild at Heart as the Palme d'Or winner at the awards ceremony,[4] the boos almost drowned out the cheers, with film critic Roger Ebert leading the vocal detractors.[18][19] Barry Gifford remembers that there was a prevailing mood that the media was hoping Lynch would fail. "All kinds of journalists were trying to cause controversy and have me say something like ‘This is nothing like the book’ or ‘He ruined my book.’ I think everybody from Time magazine to What’s On In London was disappointed when I said ‘This is fantastic. This is wonderful. It’s like a big, dark, musical comedy’".[9]

MPAA Rating

The MPAA told Lynch that the version of Wild at Heart screened at Cannes would receive an X rating in North America unless cuts were made, as the NC-17 was not in effect in 1990, at the time of the film's release.[18] The director was contractually obligated to deliver an R-rated film.[18] He made one change in the scene where a character shoots his own head off with a shotgun. Gun smoke was added to tone down the blood and hide the removal of the character's head from his body. Foreign prints were not affected.[18] The Region 1 DVD and Blu-rays contain the toned-down version of the shotgun scene.

Box office

Wild at Heart opened in the United States on August 17, 1990 in a limited release of only 532 theaters, grossing US$2,913,764 in its opening weekend.[20] It went into wide release on August 31 with 618 theaters and grossing an additional $1,858,379. The film ultimately grossed $14,560,247 in North America.[2]

Reception

The film has a rating of 65% on Rotten Tomatoes[21] and a 52 metascore at Metacritic.[22] It received mixed reviews upon its initial theatrical release.

Roger Ebert wrote in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, "He is a good director, yes. If he ever goes ahead and makes a film about what's really on his mind, instead of hiding behind sophomoric humor and the cop-out of 'parody,' he may realize the early promise of his Eraserhead. But he likes the box office prizes that go along with his pop satires, so he makes dishonest movies like this one".[23] USA Today gave the film one and a half stars out of four and said, "This attempt at a one-up also trumpets its weirdness, but this time the agenda seems forced".[24]

In his review for Sight & Sound magazine, Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote, "Perhaps the major problem is that despite Cage and Dern's best efforts, Lynch is ultimately interested only in iconography, not characters at all. When it comes to images of evil, corruption, derangement, raw passion and mutilation (roughly in that order), Wild at Heart is a veritable cornucopia".[25] Richard Combs in his review for Time wrote, "The result is a pile-up, of innocence, of evil, even of actual road accidents, without a context to give significance to the casualties or survivors".[26] Christopher Sharrett in Cineaste magazine wrote, "Lynch's characters are now so cartoony one is prone to address him more as a theorist than director, except he is not that challenging ... One is never sure what Lynch likes or dislikes, and his often striking images are too often lacking in compassion for us to accept him as a chronicler of a moribund landscape a la Fellini".[27] However, Peter Travers wrote in Rolling Stone magazine, "Starting with the outrageous and building from there, he ignites a slight love-on-the-run novel, creating a bonfire of a movie that confirms his reputation as the most exciting and innovative filmmaker of his generation".[28]

Awards and honors

Diane Ladd was nominated for Best Supporting Actress at the 1990 Academy Awards[29] and at the 1991 Golden Globes.[30] She did not win either award. Frederick Elmes was nominated for Best Cinematography and Willem Dafoe for Best Supporting Male at the 1991 Independent Spirit Awards. Elmes won in his category.[31] The film won the prestigious 1990 Palme d'Or Award at the Cannes Film Festival, and was the second of three consecutive USA movies to be awarded the honour. (The other two were Sex, Lies, and Videotape in 1989 and Barton Fink in 1991.) The film was nominated for the Grand Prix of the Belgian Syndicate of Cinema Critics. American Film Institute recognition:

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs – Nominated[32]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions - Nominated[33]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Woods, Paul, A. (2000). Wierdsville, USA: The Obsessive Universe of David Lynch. Plexus, London.

- 1 2 Wild at Heart at Box Office Mojo

- ↑ Pearson, Matt (1997). "Wild at Heart". The British Film Resource. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- 1 2 "Festival de Cannes: Wild at Heart". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 3 4 Van Gelder, Lawrence (August 17, 1990). "At the Movies". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ↑ Rowland, Mark (June 1990). "The Beasts Within". American Film.

- 1 2 Campbell, Virginia (1990). "Something Really Wild". Movieline.

- 1 2 Hoffman, Jan (August 21, 1990). "Wild Child". Village Voice.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rodley, Chris (1997). "Lynch on Lynch". Faber and Faber.

- 1 2 3 Klinghoffer, David (August 16, 1990). "Heart Set in Motion by Perfect Pair". Washington Times.

- 1 2 3 4 Salem, Rob (August 25, 1990). "The Art of Darkness". Toronto Star.

- ↑ Rugoff, Ralph (September 1990). "Wild at Heart". Premiere. pp. 80–84.

- 1 2 3 Burkett, Michael (August 15–21, 1990). "The Weird According to Lynch". New Times. pp. 39, 41.

- 1 2 McGregor, Alex (August 22–29, 1990). "Out to Lynch". Time Out. pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Rohter, Larry (August 12, 1990). "David Lynch Pushes America to the Edge". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- 1 2 "David Lynch Interview". CBC. 1990.

- ↑ Caldwell, Thomas. "David Lynch". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 2007-01-23. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ansen, David (June 4, 1990). "David Lynch's New Peak". Newsweek.

- ↑ Mathieson, Kenny (1990). "Wild at Heart". Empire.

- ↑ "Wild at Heart". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Wild at Heart at Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ Wild at Heart at Metacritic

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (August 17, 1990). "Wild at Heart". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Clark, Mike (August 17, 1990). "Wild, A Bad Joke from Lynch". USA Today.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (Autumn 1990). "The Good, The Bad & The Ugly". Sight & Sound.

- ↑ Combs, Richard (August 20, 1990). "Wild at Heart". Time.

- ↑ Sharrett, Christopher (1990). "Wild at Heart". Cineaste.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (September 6, 1990). "Wild at Heart". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ "Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ "Hollywood Foreign Press Association". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ "Film Independent's Spirit Awards". Film Independent. Archived from the original on 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ↑ AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs Nominees

- ↑ AFI'S 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Wild at Heart (film) |

- Wild at Heart at the Internet Movie Database

- Wild at Heart at Box Office Mojo

- Wild at Heart at Rotten Tomatoes

- Wild at Heart at Metacritic

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|