Blood pressure

| Blood pressure | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |

A sphygmomanometer, a device used for measuring arterial pressure | |

| MeSH | D001795 |

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure exerted by circulating blood upon the walls of blood vessels. When used without further specification, "blood pressure" usually refers to the arterial pressure in the systemic circulation. It is usually measured at a person's upper arm. Blood pressure is usually expressed in terms of the systolic (maximum) pressure over diastolic (minimum) pressure and is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). It is one of the vital signs along with respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and body temperature. Normal resting blood pressure in an adult is approximately 120/80 mm Hg.

Blood pressure varies depending on situation, activity, and disease states. It is regulated by the nervous and endocrine systems. Blood pressure that is low due to a disease state is called hypotension, and pressure that is consistently high is hypertension. Both have many causes which can range from mild to severe. Both may be of sudden onset or of long duration. Long term hypertension is a risk factor for many diseases, including kidney failure, heart disease, and stroke. Long term hypertension is more common than long term hypotension in Western countries. Long term hypertension often goes undetected because of infrequent monitoring and the absence of symptoms.

Classification

Systemic arterial pressure

| Category | systolic, mm Hg | diastolic, mm Hg |

|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

The table presented here shows the classification of blood pressure adopted by the American Heart Association for adults who are 18 years and older.[1] It assumes the values are a result of averaging resting blood pressure readings measured at two or more visits to the doctor.[3][4]

In the UK, clinic blood pressures are usually categorised into three groups; low (90/60 or lower), normal (between 90/60 and 139/80), and high (140/90 or higher).[5][6]

Blood pressure fluctuates from minute to minute and normally shows a circadian rhythm over a 24-hour period, with highest readings in the early morning and evenings and lowest readings at night.[7][8] Loss of the normal fall in blood pressure at night is associated with a greater future risk of cardiovascular disease and there is evidence that night-time blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than day-time blood pressure.[9]

Various factors, such as age and sex, influence a person's blood pressure and variations in it. In children, the normal ranges are lower than for adults and depend on height.[10] Reference blood pressure values have been developed for children in different countries, based on the distribution of blood pressure in children of these countries.[11] As adults age, systolic pressure tends to rise and diastolic tends to fall.[12] In the elderly, systolic blood pressure tends to be above the normal adult range,[13] thought to be largely because of reduced flexibility of the arteries. Also, an individual's blood pressure varies with exercise, emotional reactions, sleep, digestion and time of day (circadian rhythm).

Differences between left and right arm blood pressure measurements tend to be random and average to nearly zero if enough measurements are taken. However, in a small percentage of cases there is a consistent difference greater than 10 mm Hg which may need further investigation, e.g. for obstructive arterial disease.[14][15]

The risk of cardiovascular disease increases progressively above 115/75 mm Hg.[16] In the past, hypertension was only diagnosed if secondary signs of high arterial pressure were present, along with a prolonged high systolic pressure reading over several visits. Regarding hypotension, in practice blood pressure is considered too low only if noticeable symptoms are present.[2]

Clinical trials demonstrate that people who maintain arterial pressures at the low end of these pressure ranges have much better long term cardiovascular health. The principal medical debate concerns the aggressiveness and relative value of methods used to lower pressures into this range for those who do not maintain such pressure on their own. Elevations, more commonly seen in older people, though often considered normal, are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

| Stage | Approximate age | Systolic | Diastolic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | 1 to 12 months | 75–100 | 50–70 |

| Toddlers and preschoolers | 1 to 5 years | 80–110 | 50–80 |

| School age | 6 to 12 years | 85–120 | 50–80 |

| Adolescents | 13 to 18 years | 95–140 | 60–90 |

Mean arterial pressure

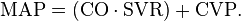

The mean arterial pressure (MAP) is the average over a cardiac cycle and is determined by the cardiac output (CO), systemic vascular resistance (SVR), and central venous pressure (CVP),[18]

MAP can be approximately determined from measurements of the systolic pressure  and the diastolic pressure

and the diastolic pressure  [18]

[18]

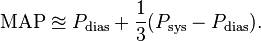

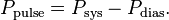

Pulse pressure

The pulse pressure is the difference between the measured systolic and diastolic pressures,[19]

The up and down fluctuation of the arterial pressure results from the pulsatile nature of the cardiac output, i.e. the heartbeat. Pulse pressure is determined by the interaction of the stroke volume of the heart, the compliance (ability to expand) of the arterial system—largely attributable to the aorta and large elastic arteries—and the resistance to flow in the arterial tree. By expanding under pressure, the aorta absorbs some of the force of the blood surge from the heart during a heartbeat. In this way, the pulse pressure is reduced from what it would be if the aorta were not compliant.[19] The loss of arterial compliance that occurs with aging explains the elevated pulse pressures found in elderly patients.

Systemic venous pressure

| Site | Normal pressure range (in mmHg)[20] | |

|---|---|---|

| Central venous pressure | 3–8 | |

| Right ventricular pressure | systolic | 15–30 |

| diastolic | 3–8 | |

| Pulmonary artery pressure | systolic | 15–30 |

| diastolic | 4–12 | |

| Pulmonary vein/ |

2–15 | |

| Left ventricular pressure | systolic | 100–140 |

| diastolic | 3-12 | |

Blood pressure generally refers to the arterial pressure in the systemic circulation. However, measurement of pressures in the venous system and the pulmonary vessels plays an important role in intensive care medicine but requires invasive measurement of pressure using a catheter.

Venous pressure is the vascular pressure in a vein or in the atria of the heart. It is much less than arterial pressure, with common values of 5 mm Hg in the right atrium and 8 mm Hg in the left atrium.

Variants of venous pressure include:

- Central venous pressure, which is a good approximation of right atrial pressure,[21] which is a major determinant of right ventricular end diastolic volume. (However, there can be exceptions in some cases.)[22]

- The jugular venous pressure (JVP) is the indirectly observed pressure over the venous system. It can be useful in the differentiation of different forms of heart and lung disease.

- The portal venous pressure is the blood pressure in the portal vein. It is normally 5–10 mm Hg[23]

Pulmonary pressure

Normally, the pressure in the pulmonary artery is about 15 mm Hg at rest.[24]

Increased blood pressure in the capillaries of the lung cause pulmonary hypertension, leading to interstitial edema if the pressure increases to above 20 mm Hg, and to pulmonary edema at pressures above 25 mm Hg.[25]

Disorders

Disorders of blood pressure control include: high blood pressure, low blood pressure, and blood pressure that shows excessive or maladaptive fluctuation.

High

Arterial hypertension can be an indicator of other problems and may have long-term adverse effects. Sometimes it can be an acute problem, for example hypertensive emergency.

Levels of arterial pressure put mechanical stress on the arterial walls. Higher pressures increase heart workload and progression of unhealthy tissue growth (atheroma) that develops within the walls of arteries. The higher the pressure, the more stress that is present and the more atheroma tend to progress and the heart muscle tends to thicken, enlarge and become weaker over time.

Persistent hypertension is one of the risk factors for strokes, heart attacks, heart failure and arterial aneurysms, and is the leading cause of chronic kidney failure. Even moderate elevation of arterial pressure leads to shortened life expectancy. At severely high pressures, mean arterial pressures 50% or more above average, a person can expect to live no more than a few years unless appropriately treated.[26]

In the past, most attention was paid to diastolic pressure; but nowadays it is recognised that both high systolic pressure and high pulse pressure (the numerical difference between systolic and diastolic pressures) are also risk factors. In some cases, it appears that a decrease in excessive diastolic pressure can actually increase risk, due probably to the increased difference between systolic and diastolic pressures (see the article on pulse pressure). If systolic blood pressure is elevated (>140) with a normal diastolic blood pressure (<90), it is called "isolated systolic hypertension" and may present a health concern.[27][28]

For those with heart valve regurgitation, a change in its severity may be associated with a change in diastolic pressure. In a study of people with heart valve regurgitation that compared measurements 2 weeks apart for each person, there was an increased severity of aortic and mitral regurgitation when diastolic blood pressure increased, whereas when diastolic blood pressure decreased, there was a decreased severity.[29]

Low

Blood pressure that is too low is known as hypotension. Hypotension is a medical concern if it causes signs or symptoms, such as dizziness, fainting, or in extreme cases, shock.[4]

When arterial pressure and blood flow decrease beyond a certain point, the perfusion of the brain becomes critically decreased (i.e., the blood supply is not sufficient), causing lightheadedness, dizziness, weakness or fainting.[30]

Sometimes the arterial pressure drops significantly when a patient stands up from sitting. This is known as orthostatic hypotension (postural hypotension); gravity reduces the rate of blood return from the body veins below the heart back to the heart, thus reducing stroke volume and cardiac output.

When people are healthy, the veins below their heart quickly constrict and the heart rate increases to minimize and compensate for the gravity effect. This is carried out involuntarily by the autonomic nervous system. The system usually requires a few seconds to fully adjust and if the compensations are too slow or inadequate, the individual will suffer reduced blood flow to the brain, dizziness and potential blackout. Increases in G-loading, such as routinely experienced by aerobatic or combat pilots 'pulling Gs', greatly increases this effect. Repositioning the body perpendicular to gravity largely eliminates the problem.

Other causes of low arterial pressure include:

- Sepsis

- Hemorrhage – blood loss

- Toxins including toxic doses of blood pressure medicine

- Hormonal abnormalities, such as Addison's disease

- Eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa and bulimia

Shock is a complex condition which leads to critically decreased perfusion. The usual mechanisms are loss of blood volume, pooling of blood within the veins reducing adequate return to the heart and/or low effective heart pumping. Low arterial pressure, especially low pulse pressure, is a sign of shock and contributes to and reflects decreased perfusion.

If there is a significant difference in the pressure from one arm to the other, that may indicate a narrowing (for example, due to aortic coarctation, aortic dissection, thrombosis or embolism) of an artery.

Fluctuating blood pressure

Normal fluctuation in blood pressure is adaptive and necessary. Fluctuations in pressure that are significantly greater than the norm are associated with greater white matter hyperintensity, a finding consistent with reduced local cerebral blood flow[31] and a heightened risk of cerebrovascular disease.[32] Within both high and low blood pressure groups, a greater degree of fluctuation was found to correlate with an increase in cerebrovascular disease compared to those with less variability, suggesting the consideration of the clinical management of blood pressure fluctuations, even among normotensive older adults.[32] Older individuals and those who had received blood pressure medications were more likely to exhibit larger fluctuations in pressure.[32]

Physiology

During each heartbeat, blood pressure varies between a maximum (systolic) and a minimum (diastolic) pressure.[33] The blood pressure in the circulation is principally due to the pumping action of the heart.[34] Differences in mean blood pressure are responsible for blood flow from one location to another in the circulation. The rate of mean blood flow depends on both blood pressure and the resistance to flow presented by the blood vessels. Mean blood pressure decreases as the circulating blood moves away from the heart through arteries and capillaries due to viscous losses of energy. Mean blood pressure drops over the whole circulation, although most of the fall occurs along the small arteries and arterioles.[35] Gravity affects blood pressure via hydrostatic forces (e.g., during standing), and valves in veins, breathing, and pumping from contraction of skeletal muscles also influence blood pressure in veins.[34]

Hemodynamics

There are many physical factors that influence arterial pressure. Each of these may in turn be influenced by physiological factors, such as: diet, exercise, disease, drugs or alcohol, stress, and obesity.[36]

Some physical factors are:

- Volume of fluid or blood volume, the amount of blood that is present in the body. The more blood present in the body, the higher the rate of blood return to the heart and the resulting cardiac output. There is some relationship between dietary salt intake and increased blood volume, potentially resulting in higher arterial pressure, though this varies with the individual and is highly dependent on autonomic nervous system response and the renin–angiotensin system.[37][38][39]

- Resistance. In the circulatory system, this is the resistance of the blood vessels. The higher the resistance, the higher the arterial pressure upstream from the resistance to blood flow. Resistance is related to vessel radius (the larger the radius, the lower the resistance), vessel length (the longer the vessel, the higher the resistance), blood viscosity, as well as the smoothness of the blood vessel walls. Smoothness is reduced by the buildup of fatty deposits on the arterial walls. Substances called vasoconstrictors can reduce the size of blood vessels, thereby increasing blood pressure. Vasodilators (such as nitroglycerin) increase the size of blood vessels, thereby decreasing arterial pressure. Resistance, and its relation to volumetric flow rate (Q) and pressure difference between the two ends of a vessel are described by Poiseuille's Law.

- Viscosity, or thickness of the fluid. If the blood gets thicker, the result is an increase in arterial pressure. Certain medical conditions can change the viscosity of the blood. For instance, anemia (low red blood cell concentration), reduces viscosity, whereas increased red blood cell concentration increases viscosity. It had been thought that aspirin and related "blood thinner" drugs decreased the viscosity of blood, but instead studies found[40] that they act by reducing the tendency of the blood to clot.

In practice, each individual's autonomic nervous system responds to and regulates all these interacting factors so that, although the above issues are important, the actual arterial pressure response of a given individual varies widely because of both split-second and slow-moving responses of the nervous system and end organs. These responses are very effective in changing the variables and resulting blood pressure from moment to moment.

Moreover, blood pressure is the result of cardiac output increased by peripheral resistance: blood pressure = cardiac output X peripheral resistance. As a result, an abnormal change in blood pressure is often an indication of a problem affecting the heart's output, the blood vessels' resistance, or both. Thus, knowing the patient's blood pressure is critical to assess any pathology related to output and resistance.

Regulation

The endogenous regulation of arterial pressure is not completely understood, but the following mechanisms of regulating arterial pressure have been well-characterized:

- Baroreceptor reflex: Baroreceptors in the high pressure receptor zones detect changes in arterial pressure. These baroreceptors send signals ultimately to the medulla of the brain stem, specifically to the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM). The medulla, by way of the autonomic nervous system, adjusts the mean arterial pressure by altering both the force and speed of the heart's contractions, as well as the total peripheral resistance. The most important arterial baroreceptors are located in the left and right carotid sinuses and in the aortic arch.[41]

- Renin-angiotensin system (RAS): This system is generally known for its long-term adjustment of arterial pressure. This system allows the kidney to compensate for loss in blood volume or drops in arterial pressure by activating an endogenous vasoconstrictor known as angiotensin II.

- Aldosterone release: This steroid hormone is released from the adrenal cortex in response to angiotensin II or high serum potassium levels. Aldosterone stimulates sodium retention and potassium excretion by the kidneys. Since sodium is the main ion that determines the amount of fluid in the blood vessels by osmosis, aldosterone will increase fluid retention, and indirectly, arterial pressure.

- Baroreceptors in low pressure receptor zones (mainly in the venae cavae and the pulmonary veins, and in the atria) result in feedback by regulating the secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH/Vasopressin), renin and aldosterone. The resultant increase in blood volume results in an increased cardiac output by the Frank–Starling law of the heart, in turn increasing arterial blood pressure.

These different mechanisms are not necessarily independent of each other, as indicated by the link between the RAS and aldosterone release. When blood pressure falls many physiological cascades commence in order to return the blood pressure to a more appropriate level.

- The blood pressure fall is detected by a decrease in blood flow and thus a decrease in Glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

- Decrease in GFR is sensed as a decrease in Na+ levels by the macula densa.

- The macula densa cause an increase in Na+ reabsorption, which causes water to follow in via osmosis and leads to an ultimate increase in plasma volume. Further, the macula densa releases adenosine which causes constriction of the afferent arterioles.

- At the same time, the juxtaglomerular cells sense the decrease in blood pressure and release renin.

- Renin converts angiotensinogen (inactive form) to angiotensin I (active form).

- Angiotensin I flows in the bloodstream until it reaches the capillaries of the lungs where angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) acts on it to convert it into angiotensin II.

- Angiotensin II is a vasoconstrictor which will increase bloodflow to the heart and subsequently the preload, ultimately increasing the cardiac output.

- Angiotensin II also causes an increase in the release of aldosterone from the adrenal glands.

- Aldosterone further increases the Na+ and H2O reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule of the nephron.

Currently, the RAS is targeted pharmacologically by ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists. The aldosterone system is directly targeted by spironolactone, an aldosterone antagonist. The fluid retention may be targeted by diuretics; the antihypertensive effect of diuretics is due to its effect on blood volume. Generally, the baroreceptor reflex is not targeted in hypertension because if blocked, individuals may suffer from orthostatic hypotension and fainting.

Measurement

Arterial pressure is most commonly measured via a sphygmomanometer, which historically used the height of a column of mercury to reflect the circulating pressure.[42] Blood pressure values are generally reported in millimetres of mercury (mm Hg), though aneroid and electronic devices do not contain mercury.

For each heartbeat, blood pressure varies between systolic and diastolic pressures. Systolic pressure is peak pressure in the arteries, which occurs near the end of the cardiac cycle when the ventricles are contracting. Diastolic pressure is minimum pressure in the arteries, which occurs near the beginning of the cardiac cycle when the ventricles are filled with blood. An example of normal measured values for a resting, healthy adult human is 120 mm Hg systolic and 80 mm Hg diastolic (written as 120/80 mm Hg, and spoken as "one-twenty over eighty").

Systolic and diastolic arterial blood pressures are not static but undergo natural variations from one heartbeat to another and throughout the day (in a circadian rhythm). They also change in response to stress, nutritional factors, drugs, disease, exercise, and momentarily from standing up. Sometimes the variations are large. Hypertension refers to arterial pressure being abnormally high, as opposed to hypotension, when it is abnormally low. Along with body temperature, respiratory rate, and pulse rate, blood pressure is one of the four main vital signs routinely monitored by medical professionals and healthcare providers.[43]

Measuring pressure invasively, by penetrating the arterial wall to take the measurement, is much less common and usually restricted to a hospital setting.

Noninvasive

The noninvasive auscultatory and oscillometric measurements are simpler and quicker than invasive measurements, require less expertise, have virtually no complications, are less unpleasant and less painful for the patient. However, noninvasive methods may yield somewhat lower accuracy and small systematic differences in numerical results. Noninvasive measurement methods are more commonly used for routine examinations and monitoring.

Palpation

A minimum systolic value can be roughly estimated by palpation, most often used in emergency situations, but should be used with caution.[44] It has been estimated that, using 50% percentiles, carotid, femoral and radial pulses are present in patients with a systolic blood pressure > 70 mm Hg, carotid and femoral pulses alone in patients with systolic blood pressure of > 50 mm Hg, and only a carotid pulse in patients with a systolic blood pressure of > 40 mm Hg.[44]

A more accurate value of systolic blood pressure can be obtained with a sphygmomanometer and palpating the radial pulse.[45] The diastolic blood pressure cannot be estimated by this method. The American Heart Association recommends that palpation be used to get an estimate before using the auscultatory method.

Auscultatory

The auscultatory method (from the Latin word for "listening") uses a stethoscope and a sphygmomanometer. This comprises an inflatable (Riva-Rocci) cuff placed around the upper arm at roughly the same vertical height as the heart, attached to a mercury or aneroid manometer. The mercury manometer, considered the gold standard, measures the height of a column of mercury, giving an absolute result without need for calibration and, consequently, not subject to the errors and drift of calibration which affect other methods. The use of mercury manometers is often required in clinical trials and for the clinical measurement of hypertension in high-risk patients, such as pregnant women.

A cuff of appropriate size[46] is fitted smoothly and also snugly, then inflated manually by repeatedly squeezing a rubber bulb until the artery is completely occluded. It is important that the cuff size is correct: undersized cuffs record too high a pressure; oversized cuffs may yield too low a pressure.[47] Usually three or four cuff sizes should be available to allow measurements in arms of different size.[47] Listening with the stethoscope to the brachial artery at the antecubital area of the elbow, the examiner slowly releases the pressure in the cuff. When blood just starts to flow in the artery, the turbulent flow creates a "whooshing" or pounding (first Korotkoff sound). The pressure at which this sound is first heard is the systolic blood pressure. The cuff pressure is further released until no sound can be heard (fifth Korotkoff sound), at the diastolic arterial pressure.

The auscultatory method is the predominant method of clinical measurement.[48]

Oscillometric

The oscillometric method was first demonstrated in 1876 and involves the observation of oscillations in the sphygmomanometer cuff pressure[49] which are caused by the oscillations of blood flow, i.e., the pulse.[50] The electronic version of this method is sometimes used in long-term measurements and general practice. It uses a sphygmomanometer cuff, like the auscultatory method, but with an electronic pressure sensor (transducer) to observe cuff pressure oscillations, electronics to automatically interpret them, and automatic inflation and deflation of the cuff. The pressure sensor should be calibrated periodically to maintain accuracy.

Oscillometric measurement requires less skill than the auscultatory technique and may be suitable for use by untrained staff and for automated patient home monitoring. As for the auscultatory technique it is important that the cuff size is appropriate for the arm. There are some single cuff devices that may be used for arms of differing sizes, although experience with these is limited.[47]

The cuff is inflated to a pressure initially in excess of the systolic arterial pressure and then reduced to below diastolic pressure over a period of about 30 seconds. When blood flow is nil (cuff pressure exceeding systolic pressure) or unimpeded (cuff pressure below diastolic pressure), cuff pressure will be essentially constant. When blood flow is present, but restricted, the cuff pressure, which is monitored by the pressure sensor, will vary periodically in synchrony with the cyclic expansion and contraction of the brachial artery, i.e., it will oscillate.

Over the deflation period, the recorded pressure waveform forms a signal known as the cuff deflation curve. A bandpass filter is utilized to extract the oscillometric pulses from the cuff deflation curve. Over the deflation period, the extracted oscillometric pulses form a signal known as the oscillometric waveform (OMW). The amplitude of the oscillometric pulses increases to a maximum and then decreases with further deflation. A variety of analysis algorithms can be employed in order to estimate the systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure.

Oscillometric monitors may produce inaccurate readings in patients with heart and circulation problems, which include arteriosclerosis, arrhythmia, preeclampsia, pulsus alternans, and pulsus paradoxus.[47][51]

In practice the different methods do not give identical results; an algorithm and experimentally obtained coefficients are used to adjust the oscillometric results to give readings which match the auscultatory results as well as possible. Some equipment uses computer-aided analysis of the instantaneous arterial pressure waveform to determine the systolic, mean, and diastolic points. Since many oscillometric devices have not been validated, caution must be given as most are not suitable in clinical and acute care settings.

Recently, several coefficient-free oscillometric algorithms have developed for estimation of blood pressure. These algorithms do not rely on experimentally obtained coefficients and have been shown to provide more accurate and robust estimation of blood pressure. These algorithms are based on finding the fundamental relationship between the oscillometric waveform and the BP using modeling [52][53] and learning [54] approaches.

The term NIBP, for non-invasive blood pressure, is often used to describe oscillometric monitoring equipment.

Continuous noninvasive techniques (CNAP)

Continuous Noninvasive Arterial Pressure (CNAP) is the method of measuring arterial blood pressure in real-time without any interruptions and without cannulating the human body. CNAP combines the advantages of the following two clinical “gold standards”: it measures blood pressure continuously in real-time like the invasive arterial catheter system and it is noninvasive like the standard upper arm sphygmomanometer. Latest developments in this field show promising results in terms of accuracy, ease of use and clinical acceptance.

Non-occlusive techniques: The Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV) principle

Since the 1990s a novel family of techniques based on the so-called pulse wave velocity (PWV) principle have been developed. These techniques rely on the fact that the velocity at which an arterial pressure pulse travels along the arterial tree depends, among others, on the underlying blood pressure.[55] Accordingly, after a calibration maneuver, these techniques provide indirect estimates of blood pressure by translating PWV values into blood pressure values.[56]

The main advantage of these techniques is that it is possible to measure PWV values of a subject continuously (beat-by-beat), without medical supervision, and without the need of inflating brachial cuffs. PWV-based techniques are still in the research domain and are not adapted to clinical settings.

Ambulatory and home monitoring

Ambulatory blood pressure devices take readings regularly (e.g. every half hour throughout the day and night). They have been used to exclude measurement problems like white-coat hypertension and provide more reliable estimates of usual blood pressure and cardiovascular risk. Blood pressure readings outside of a clinical setting are usually slightly lower in the majority of people; however studies that quantified the risks from hypertension and the benefits of lowering blood pressure have mostly been based on readings in a clinical environment. Use of ambulatory measurements is not widespread but guidelines developed by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the British Hypertension Society recommended that 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring should be used for diagnosis of hypertension.[57] Health economic analysis suggested that this approach would be cost effective compared with repeated clinic measurements.[58]

Home monitoring is a cheap and simple alternative to ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, although it does not usually allow assessment of blood pressure during sleep which may be a disadvantage.[59][60] Automatic self-contained blood pressure monitors are available at reasonable prices, however measurements may not be accurate in patients with atrial fibrillation or other arrhythmias such as frequent ectopic beats.[59][60] Home monitoring may be used to improve hypertension management and to monitor the effects of lifestyle changes and medication related to blood pressure.[3] Compared to ambulatory blood pressure measurements, home monitoring has been found to be an effective and lower cost alternative,[59][61][62] but ambulatory monitoring is more accurate than both clinic and home monitoring in diagnosing hypertension.

When measuring blood pressure in the home, an accurate reading requires that one not drink coffee, smoke cigarettes, or engage in strenuous exercise for 30 minutes before taking the reading. A full bladder may have a small effect on blood pressure readings; if the urge to urinate arises, one should do so before the reading. For 5 minutes before the reading, one should sit upright in a chair with one's feet flat on the floor and with limbs uncrossed. The blood pressure cuff should always be against bare skin, as readings taken over a shirt sleeve are less accurate. The same arm should be used for all measurements. During the reading, the arm that is used should be relaxed and kept at heart level, for example by resting it on a table.[63]

Since blood pressure varies throughout the day, home measurements should be taken at the same time of day. A Joint Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association on home monitoring in 2008[60] recommended that 2 to 3 readings should be taken in the morning (after awakening, before washing/dressing, taking breakfast/drink or taking medication) and another 2 to 3 readings at night, each day over a period of 1 week. It was also recommended that the readings from the first day should be discarded and that a total of ≥12 readings (i.e. at least two readings per day for the remaining 6 days of the week) should be used for making clinical decisions.

White-coat hypertension

For some patients, blood pressure measurements taken in a doctor's office may not correctly characterize their typical blood pressure.[64] In up to 25% of patients, the office measurement is higher than their typical blood pressure. This type of error is called white-coat hypertension (WCH) and can result from anxiety related to an examination by a health care professional.[65] The misdiagnosis of hypertension for these patients can result in needless and possibly harmful medication. WCH can be reduced (but not eliminated) with automated blood pressure measurements over 15 to 20 minutes in a quiet part of the office or clinic.[66] In some cases a lower blood pressure reading occurs at the doctor's - this has been termed 'masked hypertension'.[67]

Invasive

Arterial blood pressure (BP) is most accurately measured invasively through an arterial line. Invasive arterial pressure measurement with intravascular cannulae involves direct measurement of arterial pressure by placing a cannula needle in an artery (usually radial, femoral, dorsalis pedis or brachial).

The cannula must be connected to a sterile, fluid-filled system, which is connected to an electronic pressure transducer. The advantage of this system is that pressure is constantly monitored beat-by-beat, and a waveform (a graph of pressure against time) can be displayed. This invasive technique is regularly employed in human and veterinary intensive care medicine, anesthesiology, and for research purposes.

Cannulation for invasive vascular pressure monitoring is infrequently associated with complications such as thrombosis, infection, and bleeding. Patients with invasive arterial monitoring require very close supervision, as there is a danger of severe bleeding if the line becomes disconnected. It is generally reserved for patients where rapid variations in arterial pressure are anticipated.

Invasive vascular pressure monitors are pressure monitoring systems designed to acquire pressure information for display and processing. There are a variety of invasive vascular pressure monitors for trauma, critical care, and operating room applications. These include single pressure, dual pressure, and multi-parameter (i.e. pressure / temperature). The monitors can be used for measurement and follow-up of arterial, central venous, pulmonary arterial, left atrial, right atrial, femoral arterial, umbilical venous, umbilical arterial, and intracranial pressures.

Fetal blood pressure

In pregnancy, it is the fetal heart and not the mother's heart that builds up the fetal blood pressure to drive its blood through the fetal circulation.

The blood pressure in the fetal aorta is approximately 30 mm Hg at 20 weeks of gestation, and increases to approximately 45 mm Hg at 40 weeks of gestation.[68]

The average blood pressure for full-term infants:

Systolic 65–95 mm Hg

Diastolic 30–60 mm Hg[69]

References

- 1 2 "Understanding blood pressure readings". American Heart Association. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- 1 2 Mayo Clinic staff (2009-05-23). "Low blood pressure (hypotension) — Causes". MayoClinic.com. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- 1 2 Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ (December 2003). "Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure". Hypertension 42 (6): 1206–52. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. PMID 14656957.

- 1 2 "Diseases and conditions index – hypotension". National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ NHS choices: What is blood pressure? Retrieved 2012-03-27

- ↑ NHS choices: High blood pressure (hypertension) Retrieved 2012-03-27

- ↑ Table: Comparison of ambulatory blood pressures and urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine excretion measured at work, home, and during sleep between European–American (n = 110) and African–American (n = 51) women

- ↑ van Berge-Landry HM, Bovbjerg DH, James GD; Bovbjerg; James (October 2008). "Relationship between waking-sleep blood pressure and catecholamine changes in African-American and European-American women". Blood Press Monit 13 (5): 257–62. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283078f45. PMC 2655229. PMID 18799950. NIHMS90092.

- ↑ Hansen, T. W.; Li, Y.; Boggia, J.; Thijs, L.; Richart, T.; Staessen, J. A. (2010). "Predictive Role of the Nighttime Blood Pressure". Hypertension 57 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133900. ISSN 0194-911X.

- ↑ National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. "Blood pressure tables for children and adolescents". (Note that the median blood pressure is given by the 50th percentile and hypertension is defined by the 95th percentile for a given age, height, and gender.)

- ↑ Chiolero A (Mar 2014). "The quest for blood pressure reference values in children.". Journal of Hypertension 32 (3): 477–9. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000109. PMID 24477093.

- ↑ (Pickering et al. 2005, p. 145) See Isolated Systolic Hypertension.

- ↑ "...more than half of all Americans aged 65 or older have hypertension." (Pickering et al. 2005, p. 144)

- ↑ Eguchi K, Yacoub M, Jhalani J, Gerin W, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG (February 2007). "Consistency of blood pressure differences between the left and right arms". Arch Intern Med 167 (4): 388–93. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.4.388. PMID 17325301.

- ↑ Agarwal R, Bunaye Z, Bekele DM (March 2008). "Prognostic significance of between-arm blood pressure differences". Hypertension 51 (3): 657–62. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.104943. PMID 18212263.

- ↑ Appel LJ, Brands MW, Daniels SR, Karanja N, Elmer PJ, Sacks FM (February 2006). "Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association". Hypertension 47 (2): 296–308. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000202568.01167.B6. PMID 16434724.

- ↑ PEDIATRIC AGE SPECIFIC, p. 6. Revised 6/10. By Theresa Kirkpatrick and Kateri Tobias. UCLA Health System

- 1 2 Klabunde, RE (2007). "Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts – Mean Arterial Pressure". Retrieved 2008-09-29. Archived version 2009-10-03

- 1 2 Klabunde, RE (2007). "Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts – Pulse Pressure". Retrieved 2008-10-02. Archived version 2009-10-03

- ↑ Table 30-1 in: Trudie A Goers; Washington University School of Medicine Department of Surgery; Klingensmith, Mary E; Li Ern Chen; Sean C Glasgow (2008). The Washington manual of surgery. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7447-0.

- ↑ "Central Venous Catheter Physiology". Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ Tkachenko BI, Evlakhov VI, Poyasov IZ (2002). "Independence of changes in right atrial pressure and central venous pressure". Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 134 (4): 318–20. doi:10.1023/A:1021931508946. PMID 12533747.

- ↑ "Esophageal Varices : Article Excerpt by: Samy A Azer". eMedicine. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ↑ What Is Pulmonary Hypertension? From Diseases and Conditions Index (DCI). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Last updated September 2008. Retrieved on 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Chapter 41, page 210 in: Cardiology secrets By Olivia Vynn Adair Edition: 2, illustrated Published by Elsevier Health Sciences, 2001 ISBN 1-56053-420-6, ISBN 978-1-56053-420-4

- ↑ Textbook of Medical Physiology, 7th Ed., Guyton & Hall, Elsevier-Saunders, ISBN 0-7216-0240-1, p. 220.

- ↑ "Isolated systolic hypertension: A health concern? – MayoClinic.com". Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ↑ "Clinical Management of Isolated Systolic Hypertension". Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ↑ Gottdiener JS, Panza JA, St John Sutton M, Bannon P, Kushner H, Weissman NJ (July 2002). "Testing the test: The reliability of echocardiography in the sequential assessment of valvular regurgitation". American Heart Journal 144 (1): 115–21. doi:10.1067/mhj.2002.123139. PMID 12094197. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Franco Folino A (2007). "Cerebral autoregulation and syncope". Prog Cardiovasc Dis 50 (1): 49–80. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2007.01.001. PMID 17631437.

- ↑ Thomas AJ, Perry R, Barber R, Kalaria RN, O'Brien JT (2002). "Pathologies and Pathological Mechanisms for White Matter Hyperintensities in Depression". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 977: 333–339. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04835.x. PMID 12480770.

- 1 2 3 Brickman AM, Reitz C, Luchsinger JA, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Muraskin J, DeCarli C, Brown TR, Mayeux R (2010). "Long-term Blood Pressure Fluctuation and Cerebrovascular Disease in an Elderly Cohort". Archives of Neurology 67 (5): 564–569. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.70. PMC 2917204. PMID 20457955.

- ↑ "Normal Blood Pressure Range Adults". Health and Life.

- 1 2 Caro, Colin G. (1978). The Mechanics of The Circulation. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-263323-6.

- ↑ Klabunde, Richard (2005). Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 93–4. ISBN 978-0-7817-5030-1.

- ↑ Archived April 27, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Freis ED (1976). "Salt, volume and the prevention of hypertension". Circulation 53 (4): 589–95. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.53.4.589. PMID 767020. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Caplea A, Seachrist D, Dunphy G, Ely D (April 2001). "Sodium-induced rise in blood pressure is suppressed by androgen receptor blockade". AJP: Heart. 4 280 (4): H1793–801. PMID 11247793. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Houston, Mark (January 1986). "Sodium and Hypertension: A Review". Archives of Intern Medicine. 1 146 (1): 179–85. doi:10.1001/archinte.1986.00360130217028. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Rosenson RS, Wolff D, Green D, Boss AH, Kensey KR (February 2004). "Aspirin. Aspirin does not alter native blood viscosity". J. Thromb. Haemost. 2 (2): 340–1. doi:10.1111/j.1538-79333.2004.0615f.x. PMID 14996003.

- ↑ Klabunde, RE (2007). "Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts – Arterial Baroreceptors". Retrieved 2008-09-09. Archived version 2009-10-03

- ↑ Booth J (1977). "A short history of blood pressure measurement". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 70 (11): 793–9. PMC 1543468. PMID 341169.

- ↑ "Vital Signs (Body Temperature, Pulse Rate, Respiration Rate, Blood Pressure)". OHSU Health Information. Oregon Health & Science University. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- 1 2 Deakin CD, Low JL (September 2000). "Accuracy of the advanced trauma life support guidelines for predicting systolic blood pressure using carotid, femoral, and radial pulses: observational study". BMJ 321 (7262): 673–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7262.673. PMC 27481. PMID 10987771.

- ↑ Interpretation – Blood Pressure – Vitals, University of Florida. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ M.M. Chiappa, Y. Ostchega (2013). "Mean mid-arm circumference and blood pressure cuff sizes for U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2010". Blood Press Monitoring 18 (3): 138–143. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283617606. PMID 23604196.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mallion JM, Mancia G, et al. (2003). "European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement". J. Hypertens. 21 (5): 821–48. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000059016.82022.ca. PMID 12714851.

- ↑ (Pickering et al. 2005, p. 146) See Blood Pressure Measurement Methods.

- ↑ (Pickering et al. 2005, p. 147) See The Oscillometric Technique.

- ↑ Laurent, P (2003-09-28). "Blood Pressure & Hypertension". Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ↑ Hamzaoui O, Monnet X, Teboul JL (2013). "Pulsus paradoxus". Eur. Respir. J. 42 (6): 1696–705. doi:10.1183/09031936.00138912. PMID 23222878.

- ↑ Forouzanfar M (2014). "Ratio-independent blood pressure estimation by modeling the oscillometric waveform envelope". IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 63: 2501–2503. doi:10.1109/tim.2014.2332239.

- ↑ Forouzanfar M (2013). "Coefficient-free blood pressure estimation based on pulse transit time–cuff pressure dependence". IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 60: 1814–1824. doi:10.1109/tbme.2013.2243148.

- ↑ M. Forouzanfar, H. R. Dajani, V. Z. Groza, M. Bolic, and S. Rajan, "Feature-based neural network approach for oscillometric blood pressure estimation," IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas., vol. 60, pp. 2786–2796, Aug. 2011.

- ↑ Asmar, Roland (1999). Arterial Stiffness and Pulse Wave Velocity. Paris: Elsevier. ISBN 2-84299-148-6.

- ↑ Solà, Josep (2011). Continuous non-invasive blood pressure estimation (PDF). Zurich: ETHZ PhD dissertation.

- ↑ Hypertension Guideline 2011 [CG127] Produced in a collaboration between the British Hypertension Society and NICE. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG127/NICEGuidance/pdf/English

- ↑ Lovibond K, Jowett S, Barton P, Caulfield M, Heneghan C, Hobbs FD, et al. (2011). "Cost-effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modelling study". Lancet 378 (9798): 1219–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61184-7. PMID 21868086.

- 1 2 3 Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Narkiewicz K, Ruilope L, Rynkiewicz A, Schmieder RE, Struijker Boudier HA, Zanchetti A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Kjeldsen SE, Erdine S, Narkiewicz K, Kiowski W, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Cifkova R, Dominiczak A, Fagard R, Heagerty AM, Laurent S, Lindholm LH, Mancia G, Manolis A, Nilsson PM, Redon J, Schmieder RE, Struijker-Boudier HA, Viigimaa M, Filippatos G, Adamopoulos S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Bertomeu V, Clement D, Erdine S, Farsang C, Gaita D, Kiowski W, Lip G, Mallion JM, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, O'Brien E, Ponikowski P, Redon J, Ruschitzka F, Tamargo J, van Zwieten P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Williams B, Zamorano JL (June 2007). "2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". Eur Heart J 28 (12): 1462–536. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. PMID 17562668.

- 1 2 3 Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, Goff D (2008). "Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society Of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association". Hypertension 52 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.189011. PMID 18497371.

- ↑ Niiranen TJ, Kantola IM, Vesalainen R, Johansson J, Ruuska MJ (2006). "A comparison of home measurement and ambulatory monitoring of blood pressure in the adjustment of antihypertensive treatment". Am J Hypertens 19 (5): 468–74. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.10.017. PMID 16647616.

- ↑ Shimbo D, Pickering TG, Spruill TM, Abraham D, Schwartz JE, Gerin W (2007). "The Relative Utility of Home, Ambulatory, and Office Blood Pressures in the Prediction of End-Organ Damage". Am J Hypertens 20 (5): 476–82. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.12.011. PMC 1931502. PMID 17485006. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014.

- ↑ National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. "Tips for having your blood pressure taken".

- ↑ Elliot, Victoria Stagg (2007-06-11). "Blood pressure readings often unreliable". American Medical News (American Medical Association). Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ↑ Jhalani J, Goyal T, Clemow L, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Gerin W (2005). "Anxiety and outcome expectations predict the white-coat effect". Blood Pressure Monitoring 10 (6): 317–9. doi:10.1097/00126097-200512000-00006. PMID 16496447.

- ↑ (Pickering et al. 2005, p. 145) See White Coat Hypertension or Isolated Office Hypertension.

- ↑ (Pickering et al. 2005, p. 146) See Masked Hypertension or Isolated Ambulatory Hypertension.

- ↑ Struijk PC, Mathews VJ, Loupas T, Stewart PA, Clark EB, Steegers EA, Wladimiroff JW; Mathews; Loupas; Stewart; Clark; Steegers; Wladimiroff (October 2008). "Blood pressure estimation in the human fetal descending aorta". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 32 (5): 673–81. doi:10.1002/uog.6137. PMID 18816497.

- ↑ Sharon, S. M. & Emily, S. M. (2006). Foundations of Maternal-Newborn Nursing. (4th ed p.476). Philadelphia:Elsevier.

Further reading

- Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ; Hall; Appel; et al. (2005). "Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research". Hypertension 45 (5): 142–61. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. PMID 15611362. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blood pressure. |

- Blood Pressure Association (UK)

- About High Blood Pressure, American Heart Association

- Control of Blood Pressure, Toronto General Hospital

- Blood Pressure Chart, Vaughn's Summaries

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|