Blake's 7

| Blake's 7 | |

|---|---|

|

The logo used for the first three series of Blake's 7 | |

| Created by | Terry Nation |

| Starring |

Gareth Thomas Michael Keating Sally Knyvette Paul Darrow David Jackson Peter Tuddenham Jan Chappell Jacqueline Pearce Stephen Greif Brian Croucher Josette Simon Steven Pacey Glynis Barber |

| Theme music composer | Dudley Simpson |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of series | 4 |

| No. of episodes | 52 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) |

David Maloney (series 1-3) Vere Lorrimer (series 4) |

| Camera setup | Multi-camera |

| Running time | 50 minutes |

| Release | |

| Original network | BBC1 |

| Picture format | 625 line (576i) PAL 4:3 |

| Audio format | monaural |

| Original release | 2 January 1978 – 21 December 1981 |

| External links | |

| Website | |

Blake's 7 is a British science fiction television series produced by the BBC for broadcast on BBC1. Four 13-episode series of Blake's 7 were broadcast between 1978 and 1981. It was created by Terry Nation, who also created the Daleks for Doctor Who. The script editor was Chris Boucher. The series was inspired by a range of fictional media including Passage to Marseille, The Dirty Dozen, Robin Hood, Brave New World, Star Trek, classic Westerns and real-world political conflicts in South America and Israel.

Blake's 7 was popular from its first broadcast, watched by approximately 10 million people in the UK and shown in 25 other countries. Although many tropes of space opera are present, such as spaceships, robots, galactic empires and aliens, its budget was inadequate for its interstellar narrative. It remains well regarded for its strong characterisation, ambiguous morality and pessimistic tone. Critical responses to the programme have been polarised; reviewers praised its dystopian themes and "enormous sense of fun", and broadcaster Clive James described it as "classically awful".

A limited range of Blake's 7 merchandise was issued. Books, magazines and annuals were published. The BBC released music and sound effects from the series, and several companies made Blake's 7 toys and models. Four video compilations were released between 1985 and 1990, and the entire series was released on videocassette starting in 1991 and re-released in 1997. It was subsequently released as four DVD boxed sets between 2003 and 2006. The BBC produced two audio dramas in 1998 and 1999 that feature some original cast members, and were broadcast on Radio 4. Although proposals for live-action and animated remakes have not been realised, Blake's 7 has been revived with two series of official audio dramas, a comedic short film, a series of fan-made audio plays, and a proposed series of official novels.

Overview

Blake's 7 is a science fiction television series that was created by Terry Nation and produced by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Four series (each consisting of thirteen 50-minute episodes) were made and first broadcast in the United Kingdom between January 1978 and December 1981 on BBC 1.[1] The programme is set in the third century of the second calendar,[2] and at least 700 years in the future.[3] Blake's 7's narrative follows the exploits of political dissident Roj Blake, who leads a small group of rebels against the forces of the totalitarian Terran Federation, which rules the Earth and many colonised planets. The Federation uses mass surveillance, brainwashing and drug pacification to control its citizens. Blake discovers he was once the leader of a revolutionary group and is arrested, tried on false charges, and deported to a remote penal colony. En route he and fellow prisoners Jenna Stannis and Kerr Avon gain control of a technologically advanced alien spacecraft, which they name Liberator. Liberator's speed and weaponry are superior to Federation craft, and it also has a teleportation system that enables transport to the surface of planets. Liberator is controlled by Zen, the ship's central computer. Blake and his crew begin a campaign to damage the Federation, but are pursued by Space Commander Travis – a Federation soldier – and Servalan, the Supreme Commander and later Federation President.[4]

The composition of the titular "seven" changes throughout the series. The initial group of six characters – Blake, Vila, Gan, Jenna, Avon and Cally – included Zen as the seventh member. At the end of the first series, they capture a supercomputer called Orac. Gan is killed during the second series, after which Blake and Jenna disappear and are replaced by new characters Dayna and Tarrant. In the fourth series, Cally dies and is replaced by Soolin. Following the destruction of Liberator the computer Zen is replaced with a new computer character, Slave.

While Blake is an idealistic freedom fighter, his associates are petty crooks, smugglers and killers. Avon is a technical genius who, while outwardly exhibiting most interest in self-preservation and personal wealth, consistently acts to help others. When Blake is separated from his crew, Avon takes over as leader. At first Avon believes the Federation has been destroyed, becomes tired of killing and seeks rest. But by the middle of the third series, Avon realises that the Federation is expanding again, faster than he had originally realised, and he resumes the fight. The BBC had planned to conclude Blake's 7 at the end of its third series, but a further series was unexpectedly commissioned.[5] Some changes to the programme's format were necessary, such as the introduction of a new spacecraft, Scorpio, and new characters, Soolin and Slave.[6] Blake's 7 was watched by approximately 10 million people in the UK and was broadcast in 25 other countries.[7]

Characters

Regular characters

- Roj Blake portrayed by Gareth Thomas (leader of the Liberator crew for series 1–2). Blake is a long-term political dissident who uses the Liberator to wage war on the Federation. He is passionately opposed to the Federation's injustice and corruption, and prepared to accept loss of life in pursuit of its destruction. He thinks nothing of placing himself in danger to protect his crew or advance his cause. Although respected by many of his crew members, Avon accuses him of fanaticism and recklessness.[8]

- Kerr Avon portrayed by Paul Darrow (series 1–4). Avon is an electronics and computer expert who once attempted to steal 5 million credits from the Federation banking system. He distrusts emotion, and he attempts to pursue a code based on logic and reason. This frequently brings him into conflict with Blake. He becomes a reluctant rebel, agreeing to participate only on the basis that he will control Liberator once the Federation is destroyed. At times he appears motivated by financial gain and shows his readiness to put companions in danger in order to protect himself. He has an ambiguous and sometimes playful relationship with Servalan.[8] Avon appears in 51 of the series' 52 episodes, being absent only in the first episode "The Way Back".

- Vila Restal portrayed by Michael Keating (series 1–4). Vila is a skilled thief, lock-picker and conjurer and is usually reluctant to risk his life. His behaviour is often cowardly, and although other crew members regard him as tiresome, he has a high IQ. He has weaknesses for alcohol and women, and increasingly comes close to breaking the fourth wall while apparently talking to himself on screen.[8] Vila is the only character to appear in every episode of the series.

- Jenna Stannis portrayed by Sally Knyvette (series 1–2). Jenna is a glamorous space smuggler and skilled pilot who becomes adept at piloting Liberator. She has a great deal of affection for Blake and is loyal to him once he gains her trust.[9] In earlier episodes, Jenna stands her ground in her opinions showing no fear in challenging any male adversary.

- Cally portrayed by Jan Chappell (series 1–3). Cally is an alien guerrilla fighter from the planet Auron. She is a telepath, like all of her people, who can transmit thoughts silently to others. She later develops mind-reading, telekinesis and precognition abilities, but is also uniquely vulnerable to telepathic control by alien forces.[9] Cally develops as the moral conscience of the group, especially in later episodes in series 2 and throughout series 3.

- Dayna Mellanby portrayed by Josette Simon (series 3–4). The daughter of former dissident Hal Mellanby, Dayna is an expert in weapons technology. She is adept at designing mechanized weapons, but also appreciates the nobility of what she describes as more 'primitive' combat. Brave and loyal, but at times reckless and naive, she is often seen successfully challenging men who are supposedly accomplished fighters.[9] Her vendetta against Servalan (who murdered her father) motivates her to support Avon in fighting the Federation.

- Del Tarrant portrayed by Steven Pacey (series 3–4). Tarrant is an expert pilot who trained with the Federation before turning to illegal activities. He is ruthless and charming, and often challenges Avon's leadership. He also takes advantage of Vila's cowardice, whom he bullies into carrying out his instructions.[9]

- Olag Gan portrayed by David Jackson (series 1–2). Having killed the Federation guard who murdered his girlfriend, Gan has been implanted with an electronic "limiter" device which prevents him from ever killing again. However, he is courageous, strong and dedicated to Blake's cause.

- Soolin portrayed by Glynis Barber (series 4). Soolin is an expert gunslinger, distinctive for her apparent lack of fear or self-doubt, perhaps developed in response to the fact that her parents were murdered when she was a child. She joins the group after she is betrayed by Dorian, her partner. No one can match her speed when it comes to drawing a gun. Soolin's logical and cynical attitude proves an asset to her colleagues. On several occasions her quick thinking and poignant actions save the crew from perishing, overpowering the Cancer Assassin and surviving the Betafarl Conspiracy.

- Orac voiced by Derek Farr (first appearance) and Peter Tuddenham (series 2–4). Orac is a portable super-computer capable of reading any other computer's data and built by an inventor called Ensor. It uses a component called a Tariel cell – a universal computer component – and can access information stored on any computer that uses one. It can also control other computers. Orac dislikes work that it considers unnecessary, enjoys gathering information and has delusions of grandeur.[9]

- Zen voiced by Peter Tuddenham (series 1–3). The main computer aboard Liberator, Zen controls the craft's secondary systems, including the battle and guidance computers. It is susceptible to interference from outside influences, such as Orac. It is considered a character in its own right. It is rendered nonfunctional after Liberator is damaged by fluid particles, and is destroyed with the ship.[9]

- Slave voiced by Peter Tuddenham (series 4). Introduced in the fourth series, Slave was built and programmed by Dorian and is the master computer of Dorian's ship, Scorpio. It has a cringing personality, frequently apologetic and obsequious, and addresses Avon as "master" and others as "sir" or "madam".[9]

Other recurring characters

- Supreme Commander Servalan/Commissioner Sleer portrayed by Jacqueline Pearce. Servalan began her service career as a cadet, and rose to Supreme Commander of the Terran Federation. Her desire for power began at the age of eighteen when her lover abandoned her. Shortly before the Intergalactic War, Servalan conducts a military coup and installs herself as President. During her isolation on Terminal she is overthrown but adopts a pseudonym, Commissioner Sleer, under which she conducts a campaign of drug-induced pacification in order to regain territory for the Federation. Servalan is determined to pursue the crew of the Liberator and win control of the ship for herself.[9]

- Space Commander Travis portrayed by Stephen Greif in the first series and Brian Croucher in the second series. Travis is a dedicated and ruthless Federation officer, with the rank of Space Commander. Travis's left eye and arm were destroyed by Blake, and replaced with an eye patch and a prosthetic arm fitted with a concealed weapon. Travis is known for treating his troops well and leading them from the front, but also for his ruthlessness and contempt for human life. After his trial and conviction for killing civilians, Travis becomes increasingly obsessed with killing Blake.[9]

Sources and themes

Series creator Terry Nation pitched Blake's 7 to the BBC as "The Dirty Dozen in space", a reference to the 1967 Robert Aldrich film in which a disparate and disorganised group of convicts are sent on a suicide mission during World War II.[10] This influence shows in that some of Blake's followers are escaped convicts (Avon, Vila, Gan and Jenna). Blake's 7 also draws much of its inspiration from the legend of Robin Hood.[11] Blake's followers are not a band of "Merry Men". His diverse crew includes a corrupt computer genius (Avon), a smuggler (Jenna), a thief (Vila), a murderer (Gan), a telepathic guerrilla soldier (Cally), a computer with a mind of its own (Zen) and another wayward computer (Orac). Later additions were: a naive weapons expert (Dayna), a mercenary (Tarrant), a gunslinger (Soolin) and an obsequious computer (Slave). While Blake intends to use Liberator to strike against the Federation, the others are often reluctant followers – especially Avon. Blake and Avon's clashes over the leadership represent a conflict between idealism and cynicism, emotion and rationality, and dreams and practicality.[12] Similar conflicts arise between other characters; the courage of Blake and Avon compared with Vila's cowardice, or Avon and Jenna's scepticism of Blake's ideals compared with Gan's unswerving loyalty, Blake's mass murdering methods compared with Avon's targeted and less destructive approach.[12]

Script editor Chris Boucher, whose influence on the series grew as it progressed,[13] was inspired by Latin American revolutionaries, especially Zapata, in exploring Blake and his followers' motives and the consequences of their actions.[14] This is most evident in the episode Star One, in which Blake must confront the reality that in achieving his aim of overthrowing the Federation, he will unleash chaos and death for many innocent citizens.[13] When Avon gains control of Liberator, following Blake's disappearance after the events of Star One, he uses it initially to pursue his own agenda, avenging Anna's death. Later Avon realises that he cannot escape the Federation's reach and that he must, like Blake, resist them. In this respect, by the end of the fourth series Avon has replaced Blake.[15]

Classic films, such as the Western The Magnificent Seven, were an important influence upon Blake's 7. Chris Boucher incorporated lines from Westerns into the scripts, much to the delight of Paul Darrow, an enthusiast of the genre.[16] The final episode, Blake, was heavily inspired by The Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.[17] Blake's 7 also drew inspiration from the classic British dystopian novels Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and When the Sleeper Wakes by H. G. Wells.[13] This is most evident in the nature of the Federation, whose methods of dealing with Blake in the first episode, The Way Back, including brainwashing and show trials. These are reminiscent of the way in which the former Soviet Union dealt with its dissidents.[18] Explorations of totalitarianism in the series are not confined to the Federation – totalitarian control through religion (Cygnus Alpha), genetics (The Web) and technology (Redemption) also appear throughout.[18][19] Such authoritarian dystopias are common in Terry Nation's work, such his Doctor Who story, Genesis of the Daleks.[12]

Loyalty and trust are important themes of the series.[13] Avon is presented with several opportunities to abandon Blake. Many of Blake's schemes require co-operation and expertise from others. Characters are often betrayed by family and friends – especially Avon, whose former lover Anna Grant is eventually revealed to be a Federation agent. The theme of loyalty and trust reaches its peak during Blake and Avon's final encounter in the last episode (Blake); Blake, by now deeply paranoid, has been masquerading as a bounty hunter collaborating with the Federation as a front for his activities in recruiting and testing potential allies in the struggle, and this causes Avon and the others to mistrust him when Tarrant accuses Blake of selling them out; an ironic miscommunication between Avon and Blake precipitates the disastrous events that conclude the episode.[15] If Blake and his crew represent Robin Hood and his Merry Men, then the Federation forces, personified in the obsessive, psychopathic Space Commander Travis and his superior, the beautiful but ruthless Supreme Commander Servalan, represent Guy of Gisbourne and the Sheriff of Nottingham.[11]

A common theme in Nation's science fiction is the depiction of post-apocalyptic societies, as in several of his Doctor Who serials, for example The Daleks, Death to the Daleks and The Android Invasion and in his series Survivors, which Nation created before Blake's 7.[12] Post-apocalyptic societies feature in several Blake's 7 episodes including Duel, Deliverance, City at the Edge of the World and Terminal. Although not explicitly stated, some publicity material for the series refers to the Federation as having risen from the ashes of a nuclear holocaust on Earth.[18]

Plot summary

The series is set in a future age of interstellar travel and follows the exploits of a group of renegades and convicted criminals. Gareth Thomas played the eponymous character Roj Blake, a political dissident who is arrested, tried and convicted on false charges, and then deported from Earth to a prison planet. He and two fellow prisoners, treated as expendable, are sent to board and investigate an abandoned alien spacecraft. They get the ship working, commandeer it, rescue two more prisoners, and are joined by an alien guerrilla with telepathic abilities. In their attempts to stay ahead of their enemies and inspire others to rebel, they encounter a wide variety of cultures on different planets, and are forced to confront human and alien threats. The group conducts a campaign against the totalitarian Terran Federation until an intergalactic war occurs. Blake disappears and Kerr Avon then leads the group. When their spacecraft is destroyed and one group member dies, they commandeer an inferior craft and a base on a distant planet, from which they continue their campaign. In the final episode Avon finds Blake and, suspecting him of betraying the group, kills him. The group is then shot by Federation guards, who surround Avon in the final scene.

Series One

Roj Blake, a worker of high social status classified as "alpha-grade", lives in a domed city. Similar domes house most of the Earth's population. Blake is approached by a group of political dissidents who take him outside the city to meet their leader, Bran Foster. According to Foster, Blake was once the leader of an influential group of political activists opposed to the Federation's Earth Administration. Blake was arrested, brainwashed and coerced into making a confession denouncing the rebellion. His memory of those years was then blocked. Foster wants Blake to rejoin the dissidents. Suddenly, the meeting is interrupted by the arrival of Federation security forces, who fire on and kill the crowd of rebels. Blake, the only survivor, returns to the city, where he begins to remember his past. He is arrested, tried on false charges of child molestation and sentenced to deportation to the prison planet Cygnus Alpha.[20]

On the prison ship, London, Blake meets thief Vila Restal, smuggler Jenna Stannis, murderer Olag Gan and computer engineer Kerr Avon. The London encounters a battle between two alien space fleets and London's crew plot a course to avoid the combat zone and continue their voyage. They encounter a strange alien craft, board it and attempt to salvage it but are thwarted by the alien ship's defence mechanism. The captain of the London sends the expendable Blake, Avon, and Jenna across to the ship. Blake defeats the defence system when it tries to use memories he recently discovered were false. With Jenna as pilot, the three convicts escape in the alien craft.[21]

Blake and his crew follow the London to Cygnus Alpha in their captured ship, which they have named Liberator. They retrieve Vila and Gan, while Blake leaves the other prisoners. Blake wants to use Liberator and its new crew to attack the Federation with the others, especially Avon, as reluctant followers.[22] Blake's first target is a communications station on the planet Saurian Major. Blake infiltrates the station and is assisted by Cally, a telepathic guerrilla soldier from the planet Auron. Blake invites Cally to join the crew. With this new arrival, and including Liberator's computer, Zen, Liberator has a crew of seven.[23]

As Blake's attacks against the Federation become bolder, he has less success. Political pressure grows on the Administration with planetary leaders threatening to leave the Federation because of its inability to protect them from Blake's attacks. Rumours abound about Blake's heroism, and other rebel groups use Blake's name for their actions. Supreme Commander Servalan appoints Space Commander Travis, who has a personal vendetta against Blake, to eliminate Blake and capture Liberator. Servalan often co-opts Travis for her personal projects and uses Blake as a cover for her own activities. When Travis repeatedly fails to eliminate Blake, Servalan does not assign the task to another officer and does not use more resources to eliminate Blake.[24]

Blake meets a man called Ensor and discovers a plot by Servalan and Travis to seize a powerful computer called Orac, which is capable of communicating with any computer that uses a component called a Tariel Cell. Blake's crew are suffering from radiation sickness, but capture the device before Servalan arrives. Blake offers to perform the operation to save Ensor's life aboard the Liberator, but Ensor dies when the power cells for his artificial heart are depleted before they are able to reach Liberator. Aboard Liberator, Orac predicts the craft's destruction in the near future.[25]

Series Two

The alien race that built Liberator recaptures it. Orac's prophecy is fulfilled when it destroys an identical space vehicle.[26] Blake wants to attack the heart of the Federation and he targets the main computer control centre on Earth. Avon agrees to help on condition that Blake gives him Liberator when the Federation has been destroyed. Blake, Avon, Vila and Gan reach the control centre and find an empty room. Travis reveals that the computer centre was secretly moved years before and the old location was left as a decoy. Blake and his crew escape but Travis explodes a grenade and Gan is killed by falling rubble.[27]

Following Gan's death, Blake considers the future of the rebellion and Travis is convicted of war crimes in a Federation court martial at Space Command Headquarters based aboard a space station. Blake decides to restore his group's reputation and attacks the space station but Travis escapes and continues his vendetta against Blake.[28] Meanwhile, Blake seeks the new location of the computer control centre. He learns that it is now called Star One.[29] When Star One begins to malfunction, Servalan also becomes desperate to find its location. The centre's failure causes many problems across the Federation. Star One controls a large defensive barrier that has prevented extra-galactic incursions. Blake discovers Star One's location and finds that, with help from Travis, aliens from the Andromeda galaxy have infiltrated it. Vila discovers a fleet of alien spacecraft beyond the barrier. Travis partially disables the barrier. Blake and his crew overcome the aliens at Star One and kill Travis, but the gap in the barrier allows the aliens to invade. Jenna calls for help from the Federation, where Servalan has conducted a military coup, imposed martial law and declared herself President. Servalan dispatches the Federation's battle fleets to repel the invaders, who begin to breach the barrier. With Blake badly wounded, Liberator under Avon's direction, alone until Servalan's battle fleets arrive, fights against the aliens.[30]

Series Three

Liberator is severely damaged during the battle with the Andromedans, forcing the crew to abandon ship. The Federation defeats the alien invaders but has sustained heavy casualties and its influence in the galaxy is considerably reduced.[31] Blake and Jenna go missing and Avon takes control of Liberator. Two new additions, weapons expert Dayna Mellanby and mercenary Del Tarrant, join the remaining crew.[32] Avon is less inclined than Blake to attack the Federation but Servalan realises that if she captures Liberator, the Federation would quickly restore its former power.[33]

Servalan attempts to create clones of herself but is thwarted when the embryos are destroyed.[34] Avon decides to find the Federation agent who killed Anna Grant, his former lover. The group interrupts an attempt to overthrow Servalan and Avon discovers that Anna is alive and was previously a Federation agent named Bartolemew. Anna tries to shoot Avon in the back but Avon kills her and frees Servalan.[35] Servalan lures Avon into a trap using a faked message from Blake. Servalan finally captures Liberator and maroons the crew on an artificial planet called Terminal. However, Liberator and Zen have been irreparably damaged after flying through a cloud of corrosive fluid particles and, as Servalan leaves Terminal, the ship explodes and Servalan is apparently killed as she attempts to escape by teleporting away.[36]

Series Four

Booby traps, set by Servalan in her underground complex on Terminal, explode and kill Cally. Avon, Tarrant, Vila, and Dayna escape with Orac and are rescued by Dorian, a salvage operator. Dorian takes the crew in his spacecraft, Scorpio, to his base on the planet Xenon, where they meet his partner, Soolin. Dorian plans to drain the crew's life-force and take Orac, but he is foiled by Vila.[37] Avon completes a new teleport system for Scorpio using the technology left behind by Dorian. Soolin joins the crew and they takeover Scorpio and occupy the Xenon base. Avon gains control of Slave, Scorpio's main computer.[38]

The crew acquires an experimental new stardrive that vastly increases Scorpio's speed, making it even faster than Liberator was.[39] The Scorpio crew become concerned about the speed at which the Federation is reclaiming its former territory and discover that Servalan survived the destruction of Liberator. Now deposed as President of the Federation, she is using the pseudonym Commissioner Sleer and is enacting a pacification programme using a drug called Pylene 50. The Scorpio crew gain the formula for an antidote to Pylene-50, but this cannot reverse the drug's effects. Avon finds a way to synthesise the antidote and the crew attempt to create an alliance between independent worlds to resist the Federation in order to obtain the resources and manpower to mass produce it. They plan large-scale manufacture of the Pylene 50 antidote. One of the alliance members, Zukan, betrays the alliance to Servalan and detonates explosives on Xenon base, which is heavily damaged and the Scorpio crew are forced to abandon it.[40]

Avon tells the rest of the group that Orac has traced Blake to Gauda Prime, an agricultural planet. Blake is masquerading as a bounty hunter; his latest quarry is Arlen, whom he hopes to recruit for his rebellion. Scorpio approaches Gauda Prime and is attacked. The crew, except Tarrant, use the teleport to abandon the heavily damaged craft. Slave is rendered non-functional and Tarrant remains aboard to pilot Scorpio and is injured during a crash landing. Blake arrives, rescues and takes Tarrant to his base and purportedly captures Tarrant as bounty. Tarrant thinks that Blake has betrayed the group, and Blake lets Tarrant escape. Tarrant is nearly killed by Blake's colleagues when Avon and his crew save him, giving credence to Tarrant's accusation that Blake has betrayed them to the Federation. Becoming overwhelmingly suspicious of Blake, Avon kills him. Arlen reveals that she is a Federation officer and Federation guards arrive. Tarrant, Soolin, Vila, and Dayna are apparently killed by Federation troops, who slowly surround Avon. Avon steps over Blake's body, raises his gun and smiles. Shots ring out.[41]

Production history

Terry Nation had the idea for Blake's 7 in a moment of inspiration during a pitch meeting with Ronnie Marsh, a BBC drama executive. Marsh was intrigued and immediately commissioned a pilot script. When he had seen the draft, Marsh approved Blake's 7 for full development.[42] David Maloney, an experienced BBC director, was assigned to produce the series and Chris Boucher was engaged as script editor. Nation was commissioned to write the thirteen episodes. Boucher's task was to expand and develop Nation's first drafts into workable scripts, but this became increasingly difficult as Nation started running out of ideas. Meanwhile, Maloney was struggling with the limited budget available given the need for action and special effects. Despite these challenges Blake's 7 was very popular, with some episodes exceeding ten million viewers. A second series was quickly commissioned.[42]

The BBC engaged new writers for the subsequent series. It was decided that one of the regular characters should die, to demonstrate that Blake and his crew were not invincible. The character of Gan, played by David Jackson, was chosen because Gan had been under-used and was the least popular character. Although ratings declined compared to the first series, the BBC commissioned a third.[42] However, the team faced a major challenge when Gareth Thomas and Sally Knyvette decided not to return. New characters were required so that the story could continue without its titular character. Suggestions for a replacement actor for Blake were rejected and Avon became more prominent in the storyline. New characters Del Tarrant, portrayed by Steven Pacey, and Dayna Mellanby, portrayed by Josette Simon, were introduced.[42]

Blake's 7 was not expected to be recommissioned after the third series. Therefore, there was surprise when in 1980 a further series was announced as the third series ended. Bill Cotton, BBC Head of Television, had watched Terminal and greatly enjoyed it. He telephoned the presentation department and ordered them to make the announcement.[5] As David Maloney was unavailable, Vere Lorrimer became the producer. He introduced new characters and a new spacecraft Scorpio, and its computer Slave. Jan Chappell (who played Cally) decided that she did not want to return, and was replaced by Glynis Barber as Soolin.

Gareth Thomas made a final appearance as Blake, and insisted that his character be killed off in a definitive manner. Although the fourth series performed satisfactorily in the ratings, Blake's 7 was not renewed again and the final episode had an ambiguous finale. Except for Blake, whose death was contractual, the characters were shown being attacked in such a way that their survival would have been possible had a fifth series been commissioned. The final episode Blake was broadcast on 21 December 1981.[42]

Filming locations

In episode eleven of the first season "Bounty", the production filmed at Waterloo Tower at Quex Park in Kent was the ex-president Sarkoff's residence in exile.[43]

Music and sound effects

Blake's 7's signature music was written by Australian composer Dudley Simpson, who had composed music for Doctor Who for over ten years. The same recording of Simpson's theme was used for the opening titles of all four series of the programme.[44] For the fourth series, a new recording was made for the closing credits that used an easy listening-style arrangement.[45] Simpson also provided the incidental music for all of the episodes except for the Series One episode "Duel" and the Series Two episode "Gambit". "Duel" was directed by Douglas Camfield, who bore a personal grudge against Simpson and refused to work with him, and so Camfield used library music.[46] Elizabeth Parker provided the music and sound effects for "Gambit". Blake's 7 made considerable use of audio effects that are described in the credits as "special sound". Many electronically generated sound effects were used, ranging from foley-style effects for props including handguns, teleport sounds, spacecraft engines, flight console buttons and background atmospheres. The special sounds for Blake's 7 were provided by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop composers Richard Yeoman-Clark and Elizabeth Parker.

Critical reception

Blake's 7 received both positive and negative reviews. The fourth episode Time Squad review by Stanley Reynolds of The Times stated, " ... nice to hear the youngsters holding their breath in anticipation of a little terror." Reynolds elaborated, "Television science fiction has got too self-consciously jokey lately. It is also nice to have each episode complete within itself, while still carrying on the saga of Blake's struggle against the 1984-ish Federation. But is that dark-haired telepathic alien girl, the latest addition to Blake's outer-space merry men, going to spell love trouble for blonde Jenna? Maid Marian never had that trouble in Sherwood Forest."[47]

In January 1998 Robert Hanks of The Independent compared the series' ethos to that of Star Trek. He wrote "If you wanted to sum up the relative position of Britain and America in this century – the ebbing away of the pink areas of the map, the fading of national self-confidence as Uncle Sam proceeded to colonise the globe with fizzy drinks and Hollywood – you could do it like this: they had Star Trek, we had Blake's 7 ... No 'boldly going' here: instead, we got the boot stamping on a human face which George Orwell offered as a vision of humanity's future in Nineteen Eighty-Four." Hanks concluded that "Blake's 7 has acquired a credibility and popularity Terry Nation can never have expected ... I think it's to do with the sheer crappiness of the series and the crappiness it attributes to the universe: it is science-fiction for the disillusioned and ironic – and that is what makes it so very British."[48]

Gavin Collinson of the British Film Institute's website Screenonline wrote "The premise of Blake's 7 held nothing remotely original. The outlaw group resisting a powerful and corrupt regime is an idea familiar from Robin Hood and beyond. He added "Blake's 7's triumph lay in its vivid characters, its tight, pacey plots and its satisfying realism...For arguably the first time since the 1950s Quatermass serials, the BBC had created a popular sci-fi/fantasy show along adult lines." His review concludes "Ultimately, the one force the rebels could not overcome proved to be the BBC's long-standing apathy towards science fiction. However, the bloody finale, in which Avon murders Blake, exemplified the programme's strengths – fearless narratives, credible but surprising character development and an enormous sense of fun."[49]

Also on the negative side, Australian broadcaster and critic Clive James called the series " ... classically awful British television SF ... no apostrophe in the title, no sense in the plot." James continued "The depraved space queen Servalan ... could never quite bring herself to volatilize the dimly heroic Blake even when she had him square in the sights of her plasmatic spasm guns. The secret of Blake’s appeal, or Blakes appeal, for the otherwise infallibly fatale Servalan remained a mystery, like the actual wattage of light bulb on which the design of Blake’s spaceship, or Blakes spaceship, was plainly based."[50] Screenwriter Nigel Kneale, whose work included The Quatermass Experiment and other science fiction, was also critical. He described "the very few bits I've seen" as "paralytically awful", claiming that "the dialogue/characterisation seemed to consist of a kind of childish squabbling."[51]

Legacy

Blake's 7's legacy to future television and film space opera was the use of moral ambiguity and dysfunctional main characters to create tension, and of long-term story arcs to aid cohesiveness. These devices can be seen in Babylon 5, Lexx, Andromeda, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Farscape, Firefly and the reimagined Battlestar Galactica. These programmes contrast with the simple good-versus-evil dualism of Star Wars, or the 'feel-good' tone and unconnected episode structure of both early Star Trek and the series' main contemporary Doctor Who.[13] Blake's 7 also influenced Hyperdrive and Aeon Flux.[52] Television playwright Dennis Potter's final work Cold Lazarus was inspired by the show.[53]

Blake's 7 remains highly regarded. A poll of United States science-fiction writers, fans and critics for John Javna's 1987 book The Best of Science Fiction placed the series 25th in popularity, despite then only having recently begun to be broadcast in the US.[54] A similar poll in Britain conducted for SFX magazine in 1999 put Blake's 7 at 16th place, with the magazine commenting that "twenty years on, TV SF is still mapping the paths first explored by Terry Nation's baby".[55] In 2005 SFX surveyed readers' top 50 British telefantasy shows of all time, and Blake's 7 was placed at number four behind The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Red Dwarf and Doctor Who.[56] A similar poll conducted by TV Zone magazine in 2003 for the top 100 cult television programmes placed Blake's 7 11th.[57]

Dutch musician Arjen Anthony Lucassen was inspired by Blake's 7 in naming his side-project Star One.[58] Star One's album Space Metal features a song called "Intergalactic Space Crusaders" based on the series. The Orb's album The Orb's Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld features a song called "A Huge Ever Growing Pulsating Brain That Rules from the Centre of the Ultraworld", which is a reference to the episode Ultraworld.

In 2004 a 15-minute comedy film entitled Blake's Junction 7 debuted at several film festivals around the world. It was directed by Ben Gregor, written by Tim Plester, and starred Mackenzie Crook, Martin Freeman, Johnny Vegas, Mark Heap and Peter Tuddenham. This parody depicted the characters taking a break at the Newport Pagnell motorway service area.[59][60] In 2006 the BBC produced a 30-minute documentary The Cult of... Blake's 7 that was first broadcast on 12 December on BBC Four, as part of a Science Fiction Britannia series.[61]

Revivals

The revival of Blake's 7 has been mooted for some years. Terry Nation raised the possibility on a number of occasions and proposed that a new series would be set some years after the existing one. Avon, living in exile like Napoleon on Elba, would be persuaded by a new group of rebels to resume the fight against the Federation.[62]

Radio and audio

In 1998 Blake's 7 returned to the BBC on the radio. The Sevenfold Crown was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 on 17 January 1998 as part of its Playhouse strand. The play was produced by Brian Lighthill and written by Barry Letts. Paul Darrow, Michael Keating, Steven Pacey, Peter Tuddenham and Jacqueline Pearce reprised their television roles, but Josette Simon and Glynis Barber were replaced by Angela Bruce as Dayna and Paula Wilcox as Soolin. The story was set during the fourth series between the episodes Stardrive and Animals. This was followed up by The Syndeton Experiment, which featured the same cast, producer and writer and was broadcast as The Saturday Play on 10 April 1999 by BBC Radio 4.[63] BBC Audiobooks released a CD of readings of Trevor Hoyle's novelisations of episodes The Way Back read by Gareth Thomas and Cygnus Alpha read by Paul Darrow.[64]

On 11 December 2006 B7 Productions announced that it had recorded a series of 36 five-minute Blake's 7 audio adventures, written by Ben Aaronovitch, Marc Platt and James Swallow.[65] This featured Derek Riddell as Blake, Colin Salmon as Avon, Daniela Nardini as Servalan, Craig Kelly as Travis, Carrie Dobro as Jenna, Dean Harris as Vila, Owen Aaronovitch as Gan, Michael Praed, Doug Bradley and India Fisher.[66] The new series was broadcast on BBC Radio 7 and repeated in mid-2010 as three hour-long episodes: Rebel (written by Ben Aaronovitch), Traitor (Marc Platt) and Liberator (James Swallow). B7 Productions also produced series of 30-minute prequel audio episodes called Blake's 7: The Early Years, which explored the earlier histories of the central characters.[67]

In 2011 Big Finish Productions, under licence from B7 Productions, announced that it would be producing a series of audio dramas called Blake’s 7: The Liberator Chronicles, which would be " ... a series of exciting, character-driven tales that remain true to the original TV series. We’re aiming for authenticity – recreating the wonder of 1978 all over again!” The company also said it would publish a series of Blake's 7 novels at a rate of two per year.[68] In January 2013 Big Finish released an initial full cast audio production, Warship. This was followed in January 2014 with a series of six full cast single disc original stories, with a second series starting in November 2014.

Several individuals and companies have produced unofficial material based upon Blake's 7. Alan Stevens, later of Magic Bullet Productions,[69] produced three unofficial audio cassettes between 1991 and 1998: Travis: The Final Act,[70] The Mark of Kane[71] and The Logic of Empire.[72] Stevens also produced a series of audio dramas called Kaldor City, created by Chris Boucher, which link the Blake's 7 universe into Boucher's Doctor Who serial The Robots of Death through the character Carnell (Scott Fredericks), whom Boucher created for the Blake's 7 episode Weapon.

Television

In April 2000 producer Andrew Mark Sewell announced that he had bought the rights to Blake's 7 from the estate of Terry Nation, and was planning to produce a TV movie set 20 years after the finale of the original series.[73] In July 2003, Sewell announced that he, Paul Darrow and Simon Moorhead had formed a consortium called 'B7 Enterprises' that had acquired the rights and was planning a TV miniseries budgeted at between five and six million US dollars. Darrow would play Avon and the series was to be televised in early 2005, depending on " ... many factors, not least financing".[74] Paul Darrow subsequently left the project in December 2003, citing "artistic differences".[75]

On 31 October 2005 B7 Enterprises announced it had appointed Drew Kaza as Non-Executive Chairman and that it was working on two Blake's 7 projects. Blake's 7: Legacy would be a two part, three hour mini-series, which would be written by Ben Aaronovitch and D. Dominic Devine. Blake's 7: The Animated Adventures would be a 26-part children's animated adventure series written by Aaronovitch, Andrew Cartmel, Marc Platt and James Swallow.[76] In an interview with Doctor Who Magazine, writer and producer Matthew Graham said that he had been involved in discussions to bring back Blake's 7. Graham's concept was that a group of young rebels would rescue Avon, who had been kept cryogenically frozen by Servalan, and then roam the galaxy in a new ship named Liberator.[77]

On 24 April 2008 television station Sky1 announced that it had commissioned two 60-minute scripts for a potential series, working alongside B7 Productions.[78] On 4 August 2010 the station said it had decided not to commission the series. B7 Productions said the decision was " ... obviously disappointing", but that the development process has resulted in the " ... dynamic reinvention of this branded series". It said it was confident it would find another partner to bring a new version of Blake’s 7 to television.[79]

In July 2012 Deadline reported that a remake for US television networks was being developed by the independent studio Georgeville Television.[80] On 22 August the Syfy network announced that Joe Pokaski would develop the script and Martin Campbell would direct the new remake.[81]

On April 9, 2013, the BBC reported that a new series of Blake's 7 would appear on SyFy.[82] Other media reported that a full-series order of thirteen episodes had been placed.[83]

Merchandise

Terry Nation had done well financially from commercial exploitation of the Doctor Who Daleks, and recognised the potential for merchandise related to Blake's 7.[84] Nation and his agent Roger Hancock discussed this with Ray Williams of BBC Merchandising in December 1976. By May 1977 twenty-seven items of merchandise had been proposed for release by companies including Palitoy, Letraset and Airfix. However, only a small quantity of these was ever made available.[10]

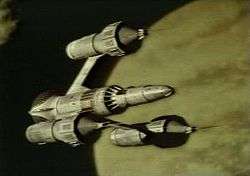

A small number of toys and models were produced. In 1978 Corgi Toys produced a two inch long die-cast model of Liberator with a transparent rear globe. The following year this was re-released in silver with a model space shuttle, and in blue on its own. Also in 1979 Blue Box Toys produced three space vehicle toys that carried the series logo; however, these had never appeared in the TV programme.[85] In 1989 Comet Miniatures produced a nine-inch long injection moulded model kit of Liberator, which contained many parts. They also produced a white metallic two-inch Liberator model, and a three-inch Federation trooper figure.[85] A Scorpio clip gun, and Liberator and Scorpio teleport bracelets, were also produced.[42]

The children's programme Blue Peter offered a cheaper home-made alternative to fans who wanted merchandise. In its 23 February 1978 show, presenter Lesley Judd demonstrated how to create a replica Liberator teleport bracelet from common household objects. This was followed up on 6 June 1983 when presenter Janet Ellis demonstrated a similar method of making a replica Scorpio bracelet.[42]

Music

The sheet music of the Blake's 7 theme was published by Chappell & Co. Ltd in 1978 with a photograph of Liberator on the front cover.[85] Dudley Simpson's theme music was also released as a single, with The Federation March (a piece of incidental music from the episode Redemption) on the B-side.[42] The Blake's 7 theme was also released on an album BBC Space Themes, and Liberator was featured on the album sleeve. Another version of the theme, 'Blake's 7 Disco', was recorded by Federation and released in 1979 on Beeb Records with a B-side unconnected with the series.[85] Many of the sound effects from the series were released in 1981 on an album BBC Sound Effects No. 26 – Sci-Fi Sound Effects, and re-released later on CD as Essential Science Fiction Sound Effects Vol. 1.[85]

Books and magazines

Blake's 7 books were produced by various authors and publishers. The first was entitled Blake's 7, written by Trevor Hoyle and Terry Nation, and published in 1978. Its US title was Blake's 7 - Their First Adventure.[85] Hoyle wrote two more books in the series: Blake's 7: Project Avalon (1979, novelising the episodes Seek–Locate–Destroy, Duel, Project Avalon, Deliverance and Orac) and Blake's 7: Scorpio Attack (1981, novelising the episodes Rescue, Traitor and Stardrive).[86] Publications continued to be issued after the series had ended. Tony Attwood's Blake's 7: The Programme Guide, published by Target in 1982, is a factual overview of the series with a detailed episode guide, an encyclopedia, and interviews with the cast and writers. It was re-issued by Virgin Books in 1994.[85] Attwood also wrote an original novel called Afterlife, which is set after the final episode and was published by Target in 1984.[85] Another original novel Avon: A Terrible Aspect by Paul Darrow told the story of Avon's early years before he met Blake, and was published in 1989.[86]

World Distributors produced Blake's 7 Annuals for 1979, 1980 and 1981. These featured stories, games, artwork and articles about space.[85] In October 1981 Marvel UK began publishing the monthly Blake's 7 magazine, which included a comic strip by Ian Kennedy as well as text stories, features and photographs. Twenty-five issues including two 'specials' were published, until the magazine closed in August 1983.[85][86] Marvel produced two 'special' magazines in 1994 and 1995, with much of the content written by TV historian Andrew Pixley and about how the series was made. Seven issues of Blake's 7 Poster Magazine were published between December 1994 and May 1995.[87]

Several books offering insight and background information to Blake's 7 were produced, including Blake's 7: The Complete Guide by Adrian Rigelsford (Boxtree, 1995), Blake's 7: The Inside Story by Joe Nazzaro and Sheelagh Wells (Virgin, 1997), A History and Critical Analysis of Blake's 7 by John Kenneth Muir (McFarland and Company, 1999), and Liberation. The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Blake's 7 by Alan Stevens and Fiona Moore (Telos, 2003).[88]

Video and DVD releases

In 1985 BBC Video issued four compilation videocassettes containing highlights from the first three series edited into 90 minute features. The first released was The Beginning, containing excerpts from The Way Back, Spacefall, Cygnus Alpha and Time Squad. Duel was released in 1986 with highlights of Seek–Locate–Destroy, Duel and Project Avalon. In the same year Orac was released, containing excerpts from Deliverance, Orac and Redemption. The first three tapes were available in both VHS and Betamax format. The final tape The Aftermath was released in Australia in 1986, with extracts from Aftermath, Powerplay and Sarcophagus. In 1990 all four tapes were re-released in the UK on VHS.[85]

From 1991 BBC Video released Blake's 7 in episodic order on 26 VHS cassettes with two episodes per tape.[42] Canadian company BFS also released these in North America. In 1997 Fabulous Films re-released these tapes in different packaging. The BBC and Fabulous Films planned to issue the series in four DVD box sets, but this was disrupted by conflicts with rights-holders B7 Enterprises. These issues were resolved and one series per year was released on Region 2 DVD between 2003 and 2006. In 2007 Amazon sold a four-series box set, but a casualty of the difficulties with Blake's 7 Enterprises was The Making of Blake's 7, a four-part documentary directed by Kevin Davies, originally intended as an extra feature with each DVD release. B7 Enterprises said they " ... did not feel [the documentary] provided a proper tribute or fresh retrospective of the show".[89] The discs contained extra features including bloopers, out-takes, alternative scenes, voiceover commentaries, interviews and behind the scenes footage.[90]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Blake's 7 |

Notes and references

- ↑ Attwood, Tony; Davies, Kevin; Emery, Rob; Ophir, Jackie (1994). "Prologue". Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. London: Virgin Books. p. 9. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- ↑ The reference to Blake’s 7 being set in the "third century of the second calendar" does not appear in the series, but is mentioned in the associated publicity material (although the Federation introducing a 'new calendar' is mentioned in the episode Pressure Point). (Pixley, Andrew (October 2002). "Blake's 7. 'The Dirty Dozen in Space'". TV Zone (156): 48–56. ISSN 0957-3844.)

- ↑ In the episode Killer, a 700-year-old space ship is encountered, one of the first deep space missions from Earth.

- ↑ Attwood, Tony; Davies, Kevin; Emery, Rob; Ophir, Jackie (1994). "The Stories". Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. London: Virgin Books. pp. 29–117. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- 1 2 Stevens, Alan; Moore, Fiona (2003). "Season D". Liberation. The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Blake's 7. England: Telos. p. 154. ISBN 1-903889-54-5.

- ↑ Fulton, Roger (1997). The Encyclopedia of TV Science Fiction (3rd ed.). London: Boxtree. pp. 66–74. ISBN 0-7522-1150-1.

- ↑ Attwood, Tony; Davies, Kevin; Emery, Rob; Ophir, Jackie (1994). Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. London: Virgin Books. p. back cover. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- 1 2 3 Attwood, Tony; Davies, Kevin; Emery, Rob; Ophir, Jackie (1994). "In Their Own Words". Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. England: Virgin Books. pp. 118–125. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Attwood, Tony; Davies, Kevin; Emery, Rob; Ophir, Jackie (1994). "The Index". Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. England: Virgin Books. pp. 128–197. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- 1 2 Pixley, Andrew (October 2002). "Blake's 7. 'The Dirty Dozen in Space'". TV Zone (156): 48–56. ISSN 0957-3844.

- 1 2 Muir, John Kenneth (2000). "A Futuristic Robin Hood Myth". A History and Critical Analysis of Blake's 7, the 1978-1981 British Television Space Adventure. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 178–181. ISBN 0-7864-2660-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Bignell, Jonathan; O'Day, Andrew (2004). "Nation, Space and Politics". Terry Nation. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. pp. 113–178. ISBN 978-0-7190-6547-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McCormack, Una (2006). "Resist the host: Blake's 7 – a very British future". In in Cook, John R. & Wright, Peter (eds.). British Science Fiction Television: A Hitchhiker's Guide. London: IB Tauris. pp. 174–192. ISBN 1-84511-048-X.

- ↑ Attwood, Tony (1982). "Interviews: Chris Boucher – Script Editor and Writer". Blake's 7. The Programme Guide. London: W.H. Allen. pp. 178–181. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- 1 2 Muir, John Kenneth (2000). "The Jurassic Arc: Science Fiction Television's First Video Novel". A History and Critical Analysis of Blake's 7, the 1978-1981 British Television Space Adventure. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 171–178. ISBN 0-7864-2660-8.

- ↑ Nazzaro, Joe; Wells, Sheelagh (1997). "Starting Out". Blake's 7: The Inside Story. London: Virgin. pp. 9–20. ISBN 0-7535-0044-2.

- ↑ Nazzaro, Joe (August 1992). "Terry Nation's Blake's 7. Part One". TV Zone (33): 28–30. ISSN 0957-3844.

- 1 2 3 Stevens, Alan; Moore, Fiona (2003). "Season A". Liberation. The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Blake's 7. England: Telos. pp. 13–58. ISBN 1-903889-54-5.

- ↑ Stevens, Alan; Moore, Fiona (2003). "Season B". Liberation. The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Blake's 7. England: Telos. pp. 59–102. ISBN 1-903889-54-5.

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Briant, Michael E. (director). (1978) The Way Back (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 2 January 1978

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Roberts, Pennant (director). (1978) Space Fall (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 9 January 1978

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Lorrimer, Vere (director). (1978) Cygnus Alpha (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 16 January 1978

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Roberts, Pennant (director). (1978) Time Squad (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 23 January 1978

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Lorrimer, Vere (director). (1978) Seek-Locate-Destroy (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 6 February 1978

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Lorrimer, Vere (director). (1978) Orac (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 27 March 1978

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Lorrimer, Vere (director). (1979) Redemption (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 1 September 1979

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Spenton-Foster, George (director). (1979) Pressure Point (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 9 February 1979

- ↑ Boucher, Chris (writer) & Martinus, Derek (director). (1979) Trial (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 13 February 1979

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Lorrimer, Vere (director). (1979) Countdown (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 1979-03-06

- ↑ Boucher, Chris (writer) & Maloney, David (director — uncredited). (1979) Star One (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 3 April 1979

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Lorrimer, Vere (director). (1980) Aftermath (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 7 January 1980

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Maloney, David (director — uncredited). (1980) Powerplay (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 7 January 1980

- ↑ Prior, Allan (writer) & McCarthy, Desmond (director). (1980) Volcano (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 14 January 1980

- ↑ Parkes, Roger (writer) & Morgan, Andrew (director). (1980) Children of Auron (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 19 February 1980

- ↑ Boucher, Chris (writer) & Cumming, Fiona (director). (1980) Rumours of Death (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 25 February 1980

- ↑ Nation, Terry (writer) & Ridge, Mary (director). (1980) Terminal (Television series episode). In Maloney, David (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 31 March 1980

- ↑ Boucher, Chris (writer) & Ridge, Mary (director). (1981) Rescue (Television series episode). In Lorrimer, Vere (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 28 September 1981

- ↑ Steed, Ben (writer) & Ridge, Mary (director). (1981) Power (Television series episode). In Lorrimer, Vere (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 5 October 1981

- ↑ Follet, Jim (writer) & Proudfoot, David Sullivan (director). (1981) Stardrive (Television series episode). In Lorrimer, Vere (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 19 October 1981

- ↑ Masters, Simon (writer) & Ritelis, Viktors (director). (1981) Warlord (Television series episode). In Lorrimer, Vere (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 14 December 1981

- ↑ Boucher, Chris (writer) & Ridge, Mary (director). (1981) Blake (Television series episode). In Lorrimer, Vere (producer), Blake's 7, London: BBC, 21 December 1981

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pixley, Andrew (1995). Blake's 7 Summer Special. ISSN 1353-761X

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Blake's 7 Article".

- ↑ Chris Brimelow. "Dudley Simpson Discography". Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- ↑ Details largely taken from documentary included Blake's 7 series 4 DVD

- ↑ "Doctor Who Magazine issue 259 , 17 December 1997 in Dr. Who/Douglas Camfield". All Experts. The New York times Company. 12 July 2005. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Reynolds, Stanley (24 January 1978). "Blake's Seven — BBC1". The Times. p. 7.

- ↑ Hanks, Robert (15 January 1998). "A Very British Space Crew". The Independent (London: Independent Digital News and Media Limited). p. 3. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Gavin Collinson. "BFI Screenonline: Blake's 7 (1978-81)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ↑ James, Clive (14 December 2005). "Clive James's literary education in sludge fiction". Times Online. Times Newspapers L:td. Archived from the original on 10 February 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ↑ Pixley, Andrew; Nigel Kneale (1986). "Nigel Kneale—Behind the Dark Door". The Quatermass Home Page. Archived from the original on 17 August 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Forever Avon" special feature on the Blakes 7 series 4 UK DVD

- ↑ Stevens, Alan; Moore, Fiona (2003). "Afterword". Liberation. The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Blake's 7. England: Telos. pp. 199–200. ISBN 1-903889-54-5.

- ↑ Muir, John Kenneth (2000). "Critical Reception". A History and Critical Analysis of Blake's 7, the 1978-1981 British Television Space Adventure. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-7864-2660-8.

- ↑ Golder, Dave (editor) (April 1999). "The Top 50 SF TV Shows of All Time". SFX (supplement to issue 50): 14.

- ↑ Bradley, Dave (editor) (2005). "The Top 50 Greatest UK Telefantasy Shows Ever". SFX Collection (22): 50–51.

- ↑ Spilsbury, Tom (June 2003). "The Top 100 Cult TV Shows Ever". TV Zone (163): 21–27.

- ↑ "Arjen Lucassen website". Arjenlucassen.com. 1 November 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "Review: Blake's Junction 7". BBC Cult. British Broadcasting Corporation. 23 September 2004. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

- ↑ Leigh Singer (20 August 2004). "Little things we like: Blake's Junction 7". Guardian Unlimited Arts. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ Stevens, Toby; Tyler, Alan (Executive Producers) & Followell, Tony (Director) (12 December 2006). The Cult of... Blake's 7 (Television programme). United Kingdom: BBC Scotland.

- ↑ Nazzaro, Joe (September 1992). "Terry Nation's Blake's 7 Part Two" (34:). TV Zone: 28–30. ISSN 0957-3844.

- ↑ Pixley, Andrew (2004). Blake's 7. The Radio Adventures [CD liner notes]. London: BBC Audiobooks

- ↑ Ben Griffiths (17 April 2009). "Fan favourite Blake's 7 revived on audio CD". BBC Worldwide Press Releases. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Blake’s 7 Reborn on Audio". Blakes7.com.

- ↑ Jonathan Thompson (24 December 2006). "Blake's 8: The Cult is Back". Independent News and Media Limited.

- ↑ "Radio 7 Programmes — Blake's 7: The Early Years, When Vila Met Gan". BBC. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Kris Heys (5 July 2011). "News: BLAKE'S 7 To Get Big Finish". Starburst Magazine Ltd. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Magic Bullet Productions". Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "Travis: The Final Act". Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ Alan Stevens. "The Mark of Kane". Magic Bullet Productions. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "The Logic of Empire". Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "Blake's 7 relaunch on film". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). 7 April 2000. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ↑ "Blake's 7 set for hi-tech return". BBC News. 28 July 2003. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ↑ "Statement by Paul Darrow with regard to the proposed Movie". Hermit.org — Judith Proctor's Blake's 7 Pages. 9 October 2003. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ↑ "B7 Productions Press Release — Appointment of Drew Kaza". Louise and Simon's Blake's 7 Fan Site. 31 October 2005. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ↑ Darlington, David (21 June 2006). "Script Doctors: Matthew Graham". Doctor Who Magazine (370): 46. ISSN 0957-9818.

- ↑ "Blake's 7 poised for Sky comeback". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). 24 April 2008. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ↑ Matthew Hemley (4 August 2010). "Sky 1 drops Blake's 7 revival". The Stage. The Stage Newspaper Limited. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Nellie Andreeva (23 July 2012). "Martin Campbell And Georgeville TV Shop Reboot Of Cult U.K. Sci-Fi Series ‘Blake’s 7′". Deadline.com. PMC. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (22 August 2012). "Syfy to Develop Cult Adventure Classic 'Blake's 7'; 'Casino Royale's' Martin Campbell to Direct, 'Heroes' Joe Pokaski to Write Pilot". TV by the Numbers. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ BBC News (9 April 2013). "Blake's 7: Classic BBC sci-fi to return on Syfy channel". bbc.co.uk. bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Louisa Mellor (9 April 2013). "blakes-7-reboot-goes-to-full-series-order". denofgeek.com. denofgeek.com. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ↑ Bignell, Jonathan; O'Day, Andrew (2004). Biographical sketch, Terry Nation. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-0-7190-6547-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Davies, Kevin; Attwood, Tony; Emery, Rob; Ophir, Jackie (1994). "The Merchandise". Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. London: Virgin Books. pp. 198–207. ISBN 0-426-19449-7.

- 1 2 3 Pixley, Andrew (Winter 1994). "A Novel Approach". Blake's 7 Winter Special: 51. ISSN 1353-761X.

- ↑ "Richard the Anorak". "Spin Offs: Poster Magazine". The Anorak's Guide to Blake's 7. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ↑ "Richard the Anorak". "Spin Offs". The Anorak's Guide to Blake's 7. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ↑ Steve Rogerson (November 2003). "What is the way forward for Blake's 7?". Louise and Simon's Blake's 7 Fan Site. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Bruce Flynn (23 October 2005). "DVD and Blu-ray Reviews and News". DVD Bits. John Zois. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

External links

- Big Finish Productions website

- Blake's 7 — B7 Enterprises, the rights holders of Blake's 7

- Down and Safe: an irreverent guide to Blakes 7

- The Anorak's Guide to Blake's 7

- Blake's 7 at BBC Programmes

- Blake's 7 at the Internet Movie Database

- Blake's 7 at TV.com

| ||||||||||||||||||