Blackford County, Indiana

| Blackford County, Indiana | |

|---|---|

|

Blackford County Courthouse in downtown Hartford City | |

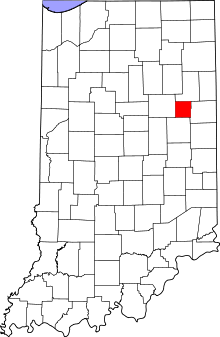

Location in the state of Indiana | |

Indiana's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | 2 April 1838 |

| Named for | Isaac Blackford |

| Seat | Hartford City |

| Largest city | Hartford City |

| Area | |

| • Total | 165.58 sq mi (429 km2) |

| • Land | 165.08 sq mi (428 km2) |

| • Water | 0.50 sq mi (1 km2), 0.30% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 12,766 |

| • Density | 77/sq mi (29.86/km²) |

| Congressional districts | 3rd, 5th |

| Time zone | Eastern: UTC-5/-4 |

| Website |

www |

| Footnotes: Indiana county number 5 | |

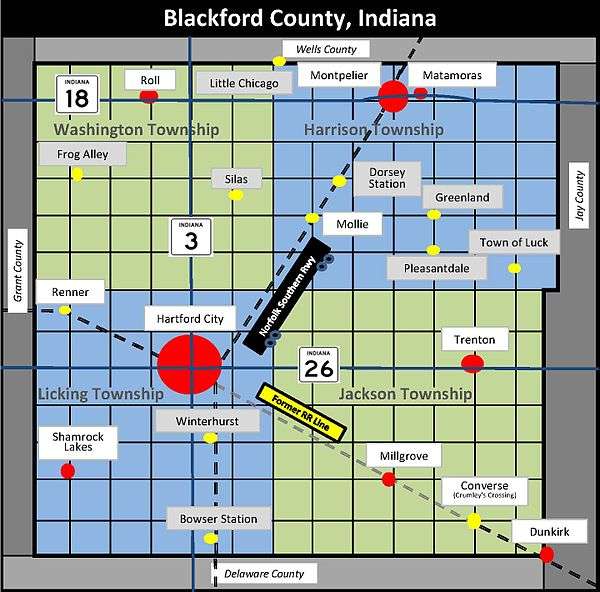

Blackford County is located in the east central portion of the U.S. state of Indiana. The county is named for Judge Isaac Blackford, who was the first speaker of the Indiana General Assembly and a long-time chief justice of the Indiana Supreme Court.[1][2] Created in 1838, Blackford County is divided into four townships, and its county seat is Hartford City.[3][4] Two incorporated cities and one incorporated town are located within the county. The county is also the site of numerous unincorporated communities and ghost towns. Occupying only 165.58 square miles (428.9 km2), Blackford County is the fourth smallest county in Indiana.[5] As of the 2010 census, the county's population is 12,766 people in 5,236 households.[6][Note 1] Based on population, the county is the 8th smallest county of the 92 in Indiana.[3] Although no interstate highways are located in Blackford County, three Indiana state roads cross the county, and an additional state road is located along the county's southeast border.[8] The county has two railroad lines. A north–south route crosses the county, and intersects with a second railroad line that connects Hartford City with communities to the west.[9]

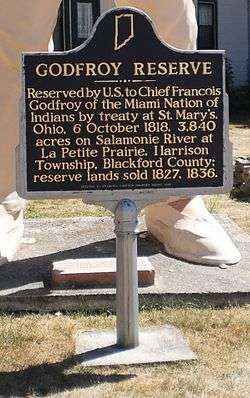

Before the arrival of European-American settlers during the 1830s, the northeastern portion of the future Blackford County was briefly the site of an Indian reservation for Chief Francois Godfroy of the Miami tribe.[10] The first European-American pioneers were typically farmers that settled near rivers where the land had drainage suitable for agriculture. Originally, the county was mostly swampland, but more land became available for farming as the marshes were cleared and drained.[11] Over the next 30 years, small communities slowly developed throughout the county. When the county's rail lines were constructed in the 1860s and 1870s, additional communities evolved around railroad stops.[12]

Beginning in the late 1880s, the discovery of natural gas and crude oil in the county (and surrounding region) caused the area to undergo an economic boom period known as the Indiana Gas Boom.[13] Manufacturers relocated to the area to take advantage of the low-cost energy and railroad facilities. The boom period lasted about 15 years, and is reflected in Blackford County's population, which peaked in 1900 at 17,213.[14] The new construction associated with the additional prosperity of the boom period caused a significant upgrade in the county's appearance, as wooden buildings were replaced with structures made with brick and stone. Much of the infrastructure built during that time remains today—including Montpelier's historic Carnegie Library and many of Hartford City's buildings in the Courthouse Square Historic District.[15][16]

Agriculture continues to be important to the county, and became even more important after the loss of several large manufacturers during the 20th century.[Note 2] Today, 72 percent of Blackford County is covered by either corn or soybean fields; additional crops, such as wheat and hay, are also grown.[Note 3]

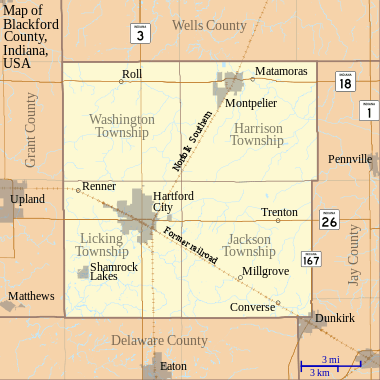

Geography

According to the 2010 census, Blackford County has a total area of 165.58 square miles (428.9 km2), of which 165.08 square miles (427.6 km2) (or 99.70%) is land and 0.50 square miles (1.3 km2) (or 0.30%) is water,[5] making it the fourth smallest county in the state. The county is located in East Central Indiana, about 55 miles (89 km) south of Fort Wayne, Indiana, and about 78 miles (126 km) northeast of Indianapolis.[Note 4] Along the north side of the county is Wells County, and on the eastern side of the county is Jay County, which separates Blackford County from Indiana's border with the state of Ohio. Delaware County is located on Blackford County's southern border, and to the west is Grant County.[22]

The county land was flattened by two glaciers millions of years ago.[23] These glaciers are also responsible for the rich Blackford County farmland that became available after the county was cleared and drained.[24] During the early 20th century, the Renner Stock Farm, in Licking Township, was known statewide for its quality cattle, hogs, and horses.[25][Note 5]

The county has some small streams and lakes, although the lakes are man-made. The Salamonie River, flowing out of Jay County (Indiana) from the east, crosses the northeast corner of Blackford County. Big and Little Lick Creek flow westward in Licking and Jackson townships in the southern half of the county.[27] Early settlers were attracted to Lick Creek, and then the Salamonie River, because the nearby land had suitable drainage for farming.[28] The county's lakes include Lake Blue Water in Harrison Township; Cain's Lake, Shamrock Lakes and Lake Mohee in Licking Township; and Lake Placid in Jackson Township.[29][30] Lake Blue Water is a spring-fed former stone quarry located one mile (1.6 km) east of Montpelier.[31] The Shamrock Lakes (a group of six lakes) were created between 1960 and 1965, and the first lake was originally intended to be a water supply for a farmer's cattle.[29]

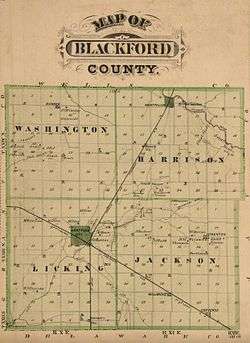

Licking and Harrison townships were original to the county. Washington Township, which is named after President George Washington, was created June 29, 1839, by the county commissioners.[32][33] Jackson Township, which is thought to be named after President Andrew Jackson, was created by the commissioners on September 22, 1839.[34][Note 6]

Communities

Two incorporated cities are located within the county, and a small portion of a third city occupies the county's southeast corner. The largest city is county seat Hartford City, located in the southern half of the county. Hartford City's population in 2010 was 6,220—well below its 1970 peak of 8,207.[Note 7][36] Another incorporated city is Montpelier, which is located on the southern banks of the Salamonie River in the northeastern part of the county. Montpelier's 2010 population was 1,805,[7] which is below its Census Bureau peak of 3,405 achieved in 1900—and less than one half of an unofficial peak of 5,000 estimated during the city's oil boom in 1895.[36][37] A small portion of the city of Dunkirk, known as Shadyside, is located in the Jackson Township portion of Blackford County, but most of Dunkirk is located in Jay County.[38] The population for the entire city of Dunkirk was 2,362 in 2010.[7] Shamrock Lakes is Blackford County's only incorporated town, achieving that status on May 21, 1973—and was the first community in Indiana to do so in 50 years.[29] Its 2010 population was 231.[7]

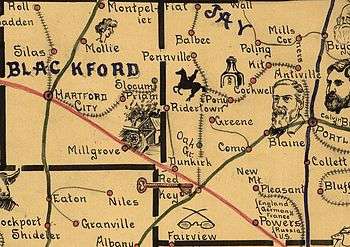

Road maps typically show five unincorporated communities in Blackford County: Converse (formerly named Crumley's Crossing), Matamoras, Millgrove, Roll (formerly named Dundee), and Trenton (former post office named Priam).[Note 8] These communities are sometimes listed as ghost towns, as nearly all businesses in these communities have closed.[39] However, residences are still maintained in these communities, and they are listed as populated places by the U.S. Geological Survey.[40] Millgrove, Roll, and Trenton all had post offices during the 19th or 20th centuries.[41]

Extinct settlements

Blackford County has over 10 communities that do not exist anymore. In some cases, a church, farm or single residence remains at the extinct community's location.[39] Among these former communities, Bowser Station, Dorsey Station, Mollie, Silas, and Slocum all had post offices during the 19th century.[41] Mollie's post office lasted until 1907.[42]

- Bowser Station—This community was a railroad stop in southern Licking Township, and had a post office during the 1870s.[41][Note 9]

- Dorsey Station—This Harrison Township community was a railroad stop, and had a post office during the 1870s.[41][43]

- Frog Alley—This Washington Township community had a church and school. The name Frog Alley was bestowed on the community because of the swampy condition of the area. The school, which began in 1863, lasted until 1923.[44]

- Greenland—Located in Harrison Township at 400 North and 600 East.[39]

- Little Chicago—Located in northwest corner of Harrison Township, and in Wells County.[39]

- Mollie—This community thrived in the 1890s as a railroad stop with a grain elevator, post office, and general store.[45] The Harrison Township oil fields were located nearby.[42]

- Pleasantdale—Located in Harrison Township, at 300 North and 600 East.[39]

- Renner—This Licking Township community was a railroad stop next to the Renner Stock Farm. Housing for the farm's employees was also located there. It thrived from the 1890s until the 1920s.[25] Renner is still listed as a populated place by the U.S. Geological Survey, but its "population" is a farm.[40]

- Silas—The Washington Township land that became the community of Silas was purchased in 1848, and the original owner established a church and school. By 1880, a general store was established at that location, and its owner was community namesake Silas Rayl. During the first decade of the 20th century, the Silas general store closed, contributing to the demise of the community.[46]

- Slocum—This community was located in southeastern Harrison Township (exact location not known), and had a post office from 1886 until 1902.[41]

- The Town of Luck—Located in Harrison Township at 250 North and 800 East.[39]

- Winterhurst—Located in Licking Township, at 200 South and 0.5 miles (0.80 km) East.[39]

History

Following thousands of years of varying cultures of indigenous peoples, the historic Miami and Delaware Indians (a.k.a. Lenape) are the first-recorded permanent settlers in the Blackford County area, living on the Godfroy Reserve after an 1818 treaty.[47] The site is located in Blackford County's Harrison Township, east of Montpelier.[48] Although the Godfroy Reserve was allotted to Miami Indian Chief Francois (a.k.a. Francis) Godfroy, Delaware Indians were also allowed to stay there.[49] The Miami tribe was the most powerful group of Indians in the region, and Francois Godfroy (who was half French) was one of their chiefs. By 1839, Godfroy had sold the reserve, and the Indians had migrated west.[47] Benjamin Reasoner was the first European–American to enter future Blackford County, and its first land owner.[50][51] He entered what would become Licking Township on July 9, 1831.[52] Reasoner and his sons built the county's first mill, which was located on the family farm.[53]

For a brief period, the land that would become Blackford County was the western part of Jay County. An act of the Indiana General Assembly, which was approved January 30, 1836, created Jay County effective after March 1, 1836.[54] In December 1836, a motion was made in the Indiana House of Representatives to review dividing Jay County, but that resolution was not adopted.[55] Two Blackford County communities, Matamoras and Montpelier, originally existed as part of Jay County. Both of these communities are located along the Salamonie River in what became the northeast portion of Blackford County. John Blount founded Matamoras, arriving in 1833.[Note 10] This village is Blackford County's oldest community, and is the site of the county's largest water mill.[45] The mill, constructed around 1843, was considered one of the finest in the state.[53] Blackford County's other former Jay County community is Montpelier, which is located west of Matamoras on the Salamonie River. Led by Abel Baldwin, the community was started in 1836 by groups of migrant settlers from Vermont. The Vermont natives named the settlement after the capital of their home state, Montpelier. Blackford County's Montpelier was platted in 1837 (before Matamoras), and is the county's oldest platted community.[56]

Several sources claim Blackford County was created in 1837.[Note 11] However, the law was not finalized until 1838. Indiana bill of the House No. 152 was originally for the creation of a county named Windsor. The name "Windsor" was replaced with the name "Blackford" by the House of Representatives in January 1838.[58] An "act for the formation of the county of Blackford" was approved on February 15, 1838.[59] This act intended that the county would be "open for business" on the first Monday in April, 1838, which was April 2.[60] However, the county was not organized.[61] Finally, on January 29, 1839, the original February 15 act was amended, stating that Blackford County shall "enjoy the rights and privileges" of an independent county. The act also appointed commissioners, and corrected a misprint that defined the southeast corner of the new county.[59][Note 12]

Over the next two years, a political "battle" continued over the location of the county seat. The tiny community of Hartford was repeatedly selected by the commissioners, but those decisions were challenged by individuals favoring Montpelier. While Licking Township (location of community of Hartford) was the most populous township in the county, the community of Montpelier was the county's oldest platted community. After a third and fourth act of the Indiana General Assembly, Hartford was finalized as the location of the county seat—and construction of a courthouse began.[63][64] Because it was discovered that another community in Indiana was also named Hartford, Blackford County's Hartford was eventually renamed Hartford City.[65]

During the next 25 years, the county grew slowly. Plans were made for roads and railroads, and swampland was drained. The first railroad line was authorized in 1849. The plan was for the Fort Wayne & Southern Railroad Company to connect the Indiana cities of Fort Wayne and Muncie—running north–south through the Blackford County communities of Montpelier and Hartford City.[66] Although work constructing the railroad line began in the 1850s, it was not completed (by connecting Fort Wayne to Muncie) until 1870, and this delay caused it to be the second railroad to operate in Blackford County.[66] By the time the railroad began operations, it was named Fort Wayne, Cincinnati & Louisville Railroad.[66] The Lake Erie and Western Railroad acquired this railroad in 1890.[67][Note 13]

The first railroad to operate in Blackford County crossed somewhat east–west through the county's southern half. The railroad was named Union and Logansport Railroad Company by the time it entered Blackford County.[69] This line was proposed in 1862, and completed to Hartford City in 1867—running through the Blackford County communities of Dunkirk, Crumley's Crossing, and Hartford City. The small community of Crumley's Crossing was renamed Converse, and two other communities (Millgrove and Renner) became established on this line. The railroad was eventually named Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and St. Louis Railroad.[66] Other names for the railroad since that time include the Panhandle division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Penn Central Railroad Company, Conrail, and Norfolk Southern Railway.[70] A portion of this line is now abandoned, and the track has been removed between Converse and Hartford City, south of State Road 26.[71]

Gas boom

In 1886, natural gas was discovered in two counties adjacent to Blackford County. The discoveries were in the small community of Eaton (south of Hartford City along railroad line) in Delaware County, and in the city of Portland in Jay County (east of Hartford City and Millgrove).[72] The Hartford City Gas & Oil Company was formed in early 1887, and successfully drilled a natural gas well later in the year. In Montpelier, the Montpelier Gas & Oil Mining company was organized in the spring of 1887.[13] While natural gas was found throughout Blackford County, crude oil was found mostly in the county's Harrison Township (somewhat between Montpelier and Mollie). Blackford County's first successful oil well, located just south of Montpelier, began producing during 1890.[73] Montpelier was thought to be "the very heart of the greatest natural gas and oil field in the world".[37] Oil was also found in parts of Washington Township, including a well that was thought to be "the most phenomenal well ever drilled in America".[74] By 1896, Blackford County had 18 natural gas companies. These companies were headquartered in all four of the county's townships, including the communities of Hartford City, Montpelier, Roll, Dunkirk, Trenton (Priam Post Office), and Millgrove.[75]

In June 1880, only 171 people held manufacturing jobs in Blackford County.[76] The Indiana Gas Boom transformed the region, as manufacturers moved to the area to utilize the natural gas and railroad system. During 1901, Indiana state inspectors visited 21 manufacturing facilities in Blackford County, and these companies employed 1,346 people (compare to 171 two decades earlier).[77] Since these inspections were in Hartford City and Montpelier only, additional manufacturing employees from the county's small communities (such as Millgrove's glass factory) could be added to the count of 1,346. The county's two largest employers were glass factories: American Window Glass plant number 3 and Sneath Glass Company.[77] Hartford City's resources (low cost energy, two railroads, and workforce) were especially favored by glass factories, and a 1904 directory lists 10 of them.[78][Note 14]

In addition to an economic transformation, another byproduct of the gas boom was an upgrade of Blackford County's appearance. Many of the county's landmark buildings were constructed during the gas boom, including the current courthouse and surrounding buildings in Hartford City's Courthouse Square Historic District.[15][80] The city's waterworks was also built during that period.[81] Additional buildings include the Carnegie Library and historic Presbyterian Church.[82] In Montpelier, many of the buildings in its Downtown Historic District were also constructed during the gas boom. Montpelier's historic Baptist Church and Montpelier's Carnegie Library were constructed in the early 1900s – near the end of the gas boom.[83]

Post-gas boom

The Indiana Gas Boom gradually came to an end during the first decade of the 20th century.[84] The end of the gas boom meant less prosperity for the county. The gas and oil workers left, some of the manufacturers moved, and the service industries were forced to close or cut back operations because of fewer customers. Adding to the county's problems, machines made the labor–intensive method originally used for producing window glass obsolete, causing many of the county's skilled glass workers at the large American Window Glass plant to lose their jobs.[85] By 1932, the window glass plant of the county's former largest employer was closed.[17][Note 15] According to the United States Census, Blackford County's population peaked at 17,123 in 1900, and it still has not returned to that zenith over 100 years later.[14]

The end of the gas boom was especially difficult for the smaller communities in the county, since the loss of a single business had more of an impact on undersized communities than it did for a town with many businesses. In the case of Millgrove, the community's major manufacturer (a glass factory) closed.[87] For other communities, such as Mollie, the loss of the gas and oil workers meant that the local post office was a "waste of time", and consumer demand at the general store was significantly diminished.[42]

Improvements to the automobile and highways, which coincided with the end of the gas boom, may have also contributed to the decline of the county's smaller communities. The automobile changed "business and shopping patterns at the expense of the small-town merchant."[88] Small town residents began to drive to larger communities to purchase goods, because of the wider selection.[88] The improved quality of automobiles and roads competed with passenger service on the railroads (and interurban lines), causing a decline in passenger traffic on the rails. Small towns associated with railroad stations suffered from the loss in traffic. In Blackford County, passenger service on the Lake Erie and Western Railroad line (owned by the Nickel Plate Road by that time) was discontinued in 1931, and the last interurban train ran on January 18, 1941.[70]

Although the natural gas and oil workers left the area after the gas (and oil) boom, Montpelier's population eventually stabilized—and Hartford City's grew. Some of the manufacturers remained in the county's two largest cities because of a lack of better alternatives. Hartford City's Sneath Glass Company, a major employer, continued operations until the 1950s.[18] Hartford City leaders attracted businesses such as Overhead Door (1923) and 3M (1955) to replace some of the companies that left the area.[89][90] Overhead Door was a major employer in Hartford City for over 60 years. A major setback for the community involving Overhead Door occurred during the 1980s, although it began in the 1960s. During the 1960s, Overhead Door moved its headquarters from Hartford City to Dallas, Texas. Its Hartford City manufacturing plant continued to be a major employer until the 1980s, when Overhead Door cut back local operations. The Hartford City facility finally closed in 2000.[19][Note 16] The county lost another major Hartford City employer in 2011 when the Key Plastics plant closed, as 200 people lost their jobs.[92]

Agriculture continues to be an important factor in the county's economy. Over 70 percent of Blackford County's land is occupied by soybean or corn fields. Additional crops and livestock are also raised. Good returns in agriculture are not always reflected in the economy of nearby towns, as industrial agriculture has reduced the number of workers it needs, and family farms have declined. Many small towns in the "Corn Belt", such as the communities in Blackford County, continue to decline in size and affluence.[93]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 1,226 | — | |

| 1850 | 2,860 | 133.3% | |

| 1860 | 4,122 | 44.1% | |

| 1870 | 6,272 | 52.2% | |

| 1880 | 8,020 | 27.9% | |

| 1890 | 10,461 | 30.4% | |

| 1900 | 17,213 | 64.5% | |

| 1910 | 15,820 | −8.1% | |

| 1920 | 14,084 | −11.0% | |

| 1930 | 13,617 | −3.3% | |

| 1940 | 13,783 | 1.2% | |

| 1950 | 14,026 | 1.8% | |

| 1960 | 14,792 | 5.5% | |

| 1970 | 15,888 | 7.4% | |

| 1980 | 15,570 | −2.0% | |

| 1990 | 14,067 | −9.7% | |

| 2000 | 14,048 | −0.1% | |

| 2010 | 12,766 | −9.1% | |

| Est. 2014 | 12,401 | [94] | −2.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[95] 1790-1960[96] 1900-1990[97] 1990-2000[98] 2010-2013[6] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, Blackford County's population density was 77.3 inhabitants per square mile (29.8/km2), well below the average for Indiana, which was 180.8 inhabitants per square mile (69.8/km2).[6] Blackford County had 12,766 people, 5,236 households, and 3,567 families residing within its borders. The racial makeup of the county was 97.7 percent white, 0.4 percent black or African American, 0.2 percent Native American, 0.1 percent Asian, 0.3 percent from other races, and 1.3 percent from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 0.9 percent of the population.[7]

The average household size was 2.41, and the average family size was 2.88. Families accounted for 68.1 percent of the county's 5,236 households, and 75.5 percent of these families included a husband and wife living together. Children under the age of 18 were living in 38.9 percent of the family households. Non-family households accounted for 31.9 percent of total households, and 86.8 percent of them were occupied by someone living alone. People 65 years and older, living alone, accounted for 40.1 percent of non-family households—or 12.8 percent of all types of households.[7]

In terms of age distribution, 22.8 percent of the population were under the age of 18, and 21.6 percent were 62 years of age or older. The median age was 42.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.7 males.[7]

As of the 2000 United States Census, the median income for a household in the county was $34,760, and the median income for a family was $41,758. Males had a median income of $30,172 versus $21,386 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,543. About 6.0 percent of families and 8.7 percent of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.3 percent of those under age 18 and 8.6 percent of those age 65 or over.[Note 17] In terms of ancestry, 16.7 percent were German, 15.5 percent were American, 9.3 percent were Irish and 7.8 percent were English.[Note 18]

Government

The county government is a constitutional body granted specific powers by the Constitution of Indiana and the Indiana Code. The county council is the legislative branch of the county government and controls all spending and revenue collection. Representatives are elected from county districts. The council members serve four-year terms and are responsible for setting salaries, the annual budget and special spending. The council also has limited authority to impose local taxes, in the form of an income and property tax that is subject to state level approval, excise taxes and service taxes.[101][102] In 2010, the county budgeted approximately $3.95 million for the district's schools and $3.18 million for other county operations and services, for a total annual budget of approximately $7.1 million.[103]

The executive body of the county is made of a board of commissioners. The commissioners are elected county-wide, in staggered terms, and each serves a four-year term. One of the commissioners, typically the most senior, serves as president. The commissioners are charged with executing the acts legislated by the council, collecting revenue and managing day-to-day functions of the county government.[101][102] The 2011 president of Blackford County's board of commissioners is Fred Walker.[104]

The county maintains a small claims court that can handle some civil cases. The judge on the court is elected to a term of four years and must be a member of the Indiana Bar Association. The judge is assisted by a constable who is elected to a four-year term. In some cases, court decisions can be appealed to the state level circuit court.[102]

The county has several other elected offices, including sheriff, coroner, auditor, treasurer, recorder, surveyor and circuit court clerk. Each of these elected officers serves a term of four years and oversees a different part of county government. Members elected to county government positions are required to declare party affiliations and be residents of the county.[102]

Each of the townships has a trustee who administers rural fire protection and ambulance service, provides poor relief and manages cemetery care, among other duties.[105] The trustee is assisted in these duties by a three-member township board. The trustees and board members are elected to four-year terms.[106]

Based on 2000 census results, Blackford County is part of Indiana's 6th congressional district, Indiana Senate district 19 and Indiana House of Representatives district 31.[107][108]

Climate and weather

| Hartford City, Indiana | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Blackford County has a typical Midwestern humid continental seasonal climate, and its Köppen climate classification is Dfa.[110] There are four distinct seasons, with winters being cold with moderate snowfall, while summers can be warm and humid.[111] In recent years, average temperatures in county seat Hartford City have ranged from a low of 18 °F (−8 °C) in January to a high of 84 °F (29 °C) in July, although a record low of −26 °F (−32 °C) was recorded in January 1994 and a record high of 103 °F (39 °C) was recorded in June 1988. Average monthly precipitation ranged from 1.94 inches (49 mm) in February to 4.33 inches (110 mm) in June.[109]

March and April are considered tornado season in Indiana.[111] Blackford County endured a category 4 storm on Palm Sunday (April 11) in 1965. This storm was one of many tornados that occurred in the Midwest on that day. Category 4 tornados have maximum speeds of 207 to 260 miles per hour (333 to 418 km/h), and this one crossed Blackford County farmland east of Roll. Although there were no fatalities in Blackford County from this tornado, two people were killed in neighboring Wells County.[112] The county has experienced at least five other tornados. The most recent tornados were two that occurred in Hartford City in 2002. However, the two Hartford City tornados were rated category 1 on the Fujita scale—much less dangerous than a category 4.[113]

Blackford County has a record for hail. Hail 4.5 inches (110 mm) in diameter fell in Hartford City on April 9, 2001. In a tie with the city of Cayuga, those hail "stones" are the largest ever recorded in the state of Indiana.[111]

The biggest recorded snow storm was the Great Blizzard of 1978, which occurred on January 26–27, 1978. A federal state of emergency was declared for Indiana at that time.[111] Indiana governor Otis R. Bowen authorized the use of National Guard equipment, facilities, and personnel throughout the state.[114] Low temperatures, high winds, and deep snow caused Hartford City to look like a ghost town, as schools and businesses closed. Wind gusts up to 45 miles per hour (72 km/h) caused snowdrifts up to 5 feet (1.5 m) high, making travel by any type of truck or automobile almost impossible. Snowmobiles were the only viable means of transportation, and volunteers from Hartford City's Snowmobile Club provided emergency assistance.[115]

Economy

Blackford County's economy is supported by a labor force of approximately 5,900 workers with an unemployment rate for June 2013 of 9.8 percent.[116] Industrial parks are located in both Montpelier and Hartford City, and both cities are served by railroad line owned by Norfolk Southern.[117][118] Over 30 employers of varying size are located in the county.[119] The Blackford County School System has the most employees, with locations in both Hartford City and Montpelier.[119] 3M Company is currently the largest manufacturer in the county, and has been located in Hartford City since its purchase of the Hartford City Paper Mill in 1955.[90] Another business employing more than 100 people is Blackford County Community Hospital, located in Hartford City.[119] Emhart Gripco is Montpelier's leading employer, with over 100 people working at its facility.[119][120]

Four categories of employment account for over 50 percent of employment in the county: manufacturing, government, retail trade, and health care.[116] The largest category is manufacturing, and it accounts for about 19 percent of the county's employed workforce. In addition to local Blackford County businesses, larger local economies in the more populous counties to the south and west offer employment and commerce, particularly in the city of Muncie in Delaware County, and the city of Marion in Grant County. Both counties employ more workers than their local workforce can provide.[121][122]

Agriculture has a significant impact on the county, although farm workers account for only about 5 percent of the county's workers.[116] In 2007, the county had 250 farms occupying 84,626 acres (34,247 ha).[123] Therefore, roughly 80 percent of Blackford County is farmland.[Note 19] Nearly 72,000 acres (29,000 ha) are devoted to the cultivation of soybeans and corn. Wheat, hay, and oats were also grown. Livestock include over 24,000 hogs and pigs.[123]

Transportation

There are no interstate highways in Blackford County, although Interstate 69 passes about 5 miles (8.0 km) to the west of the county's western border. U.S. Route 35 shares a portion of I-69's route in this area; it also does not enter Blackford County.[8]

State Road 3 enters the county from the south after passing through Eaton in neighboring Delaware County. It passes directly north through Hartford City and leaves the county near Roll, continuing north into Wells County.[124] State Road 18 runs from west to east through the north end of the county, on its way from Marion to the Ohio border; it passes through Montpelier and Matamoras.[125]

State Road 26 also runs from west to east, entering from Upland in neighboring Grant County and passing through Hartford City where it crosses State Road 3. Going on through Trenton, it enters Jay County on its way to the Ohio border.[126]

State Road 167 runs along the eastern border of the county for about 5 miles (8.0 km) as it goes north from Dunkirk; it terminates when it reaches State Road 26.[127]

A Norfolk Southern Railway railroad line enters the county from the south after leaving Eaton; it runs about a mile to the east of State Road 3 until it reaches Hartford City where it veers to the northeast and passes through Montpelier. It continues into Wells County to the north.[9] Norfolk Southern also owns Blackford County's east–west line located in the southern half of the county. An 8-mile (13 km) section of this line, between Converse and Hartford City, was abandoned during the last decade, and track has been removed.[128] The line is still in service north of State Road 26, between Hartford City and Upland in Grant County. In October 2009, Central Railroad Company of Indianapolis pursued a leasing agreement to operate the east–west line with Norfolk Southern Railway in Blackford County.[129] However, the line currently does not appear on the Central Railroad Company of Indianapolis system map.[130]

Education and health care

The county's five public schools are administered by the Blackford County School Corporation.[131] During the 2010–11 school year, a total of 1,943 students attended these schools.[132] The county school system was reorganized in 1963, after a county-wide vote favored a single school system for the entire county.[133] As a result of this decision, Hartford City and Montpelier High Schools graduated their last classes in 1969, and a new high school serving the entire county was constructed in time for the 1969–1970 school year.[133] Like the county, the new high school was named after Isaac Newton Blackford, and is called Blackford High School. The school is located a few miles north of Hartford City, and is therefore somewhat near the center of the county. The school was designed for 1,200 students, and initial enrollment totaled to 1,150 students, serving grades 9 through 12.[134] Current high school enrollment is less than 650.[135] All students in grades 7 and 8 attend Blackford Junior High School.[136] Although the county was served by eight elementary schools during the 1980s, consolidations have decreased the number of elementary schools to three.[134] Montpelier Elementary School serves grades 1 through 6, and also has kindergarten classes.[137] In Hartford City, Southside Elementary School hosts a kindergarten and grades 1 through 3, while students in grades 4 through 6 attend Northside Elementary School.[138][139]

At least four universities are located close to Blackford County. All four are located in adjacent counties, but are less than 25 miles (40 km) from Hartford City. Ball State University is the largest and most well known, and is located south of Hartford City in Muncie.[140] Muncie is also home to Ivy Tech State College-East Central.[141] Private school Indiana Wesleyan University is located in Marion, which is west of Montpelier.[142] Another private school, Taylor University, is less than 10 miles (16 km) west of Hartford City in Upland.[143]

The cities of Montpelier and Hartford City both have public libraries. The Public Library of Montpelier and Harrison Township was built in 1907 and 1908.[144] This building is also known as the Montpelier Carnegie Library because it was made possible by a grant from philanthropist (and former business magnate) Andrew Carnegie. The library was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.[145] Hartford City's Public library was also made possible by a grant from Carnegie, and it was built in 1903. The Carnegie Fund required local towns to do fundraising to match the grants, and to commit to operating the libraries after their construction. In many localities, women's groups were instrumental in organizing and doing fundraising for the libraries, both at the time of construction and since.[146] Another library located in Hartford City belongs to the Blackford County Historical Society, and a museum is housed in the same building.[147]

The Blackford County Health Department is located in Hartford City, and has a staff of nine people that serves and educates the county. Immunization and blood pressure clinics are provided in addition to educational services and emergency preparedness.[148] The county's hospital is Indiana University Health Blackford Hospital, a 15-bed facility located on Hartford City's north side. This facility was opened January 2005, and includes a medical office building and ambulance garage.[149]

Media

The first newspaper in Blackford County was The Hartford City Times, which was started by Dr. John Moler in 1852. Moler ran a drug store and print shop, and the Times was mostly an advertiser.[150] At least one source considers The Blackford County News, which was started later in 1852, as the county’s first newspaper—possibly because the Times was mostly for advertising.[151] Across the county in Montpelier, the The Montpelier Examiner was first published in 1879, and that newspaper is the predecessor of the town’s long-time newspaper, The Montpelier Herald. The county's first daily newspaper, the Evening News, was started in 1894 by Edward Everett Cox. This Hartford City newspaper was eventually renamed Hartford City News. After Cox’s death in the 1930s, the Cox family sold the Hartford City News to the owners of Hartford City’s Times-Gazette, and the combined entity became the Hartford City News-Times.[152] Changing ownership over the years, the Hartford City News-Times continued operations through the 20th century. During the 21st century, the newspaper began using the name News-Times, and calls itself "Blackford County’s only daily newspaper".[153]

The two major television markets that reach Blackford County are Indianapolis and Fort Wayne.[154] Although a few lower-powered stations are located closer to Blackford County in cities such as Muncie, Marion, and Kokomo, these stations typically do not have a broadcast range that covers all of Blackford County.[155] There are no AM radio stations based in Blackford County, but plenty of nearby areas have AM stations in broadcast range. This includes Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, Muncie, and Marion among others.[156] Plenty of FM stations are also in broadcast range, and Blackford County has FM radio stations located in Hartford City and Montpelier.[157][158][159] Hartford City, Montpelier, and portions of the county's rural areas have internet access available.[160]

Notable people

Kevin A. Ford was born in Portland, Indiana, in 1960. His family moved to Montpelier, Indiana, and he graduated from Blackford High School in 1978.[161] Ford holds four academic degrees, and retired from active duty as a colonel in the United States Air Force in 2008. He was the pilot for the Space Shuttle Discovery during its August 2009 flight, and has logged over 332 hours in outer space.[161][162] On October 23, 2012, Ford began another voyage into outer space. This time, his journey was aboard a Russian spacecraft, with the International Space Station as his destination.[163]

Clarence G. Johnson was the first president of Overhead Door Corporation, and lived in Hartford City, Indiana, from 1923 until he died in 1935.[19][89] He was a pioneer in the development of garage doors, and holds numerous patents.[Note 20] One of Johnson's more notable inventions is the first "electric operator for sectional upward-acting doors".[89] Johnson's Overhead Door Corporation was a major employer in Blackford County for over 60 years, employing as many as 515 people during its peak years.[167]

Maurice Clifford Townsend was born August 11, 1884, on a small farm in Blackford County's Licking Township.[168] After graduating from college in Marion, Indiana, Townsend served as superintendent of Blackford County schools, superintendent of Grant County schools, and as a representative of the Blackford-Grant District in the Indiana General Assembly. Townsend was elected as Indiana's lieutenant governor in 1932. He won the 1936 election for governor, and served the single four-year term allowed by law.[168] After Townsend's public service in Indiana, he served in the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and worked in agriculture related offices. Townsend's legacy is directing school buses to be painted yellow for safety and identification purposes, an idea that spread nationwide.[169]

Erika Wicoff is one of the most decorated female athletes in Indiana University history, earning three Big Ten Player of the Year awards as a golfer.[170] She was the Big Ten women's golf champion in 1994, 1995, and 1996.[170] A native of Hartford City, Indiana, she later competed in the Ladies Professional Golf Association. Wicoff was inducted into the Indiana Athletics Hall of Fame in 2006.[171]

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ In the United States Census Bureau's American Fact Finder 2010, Use Quick Start, select "Blackford County, Indiana" for geography, and "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010" for topic or table name.[7]

- ↑ The American Window Glass plant closed near the beginning of the Great Depression as fewer factories were needed because of a new window making process using machines that was much more productive than the more labor-intensive process used earlier.[17] Sneath Glass Company closed during the 1950s after plastics replaced many of the company's products.[18] The Overhead Door Company moved its headquarters to a larger city (Dallas, Texas) in 1964, and the Hartford City plant was closed in 2000 after cutbacks during the 1980s.[19]

- ↑ In 2010, 34 thousand acres of corn, and 42.4 thousand acres of soybeans, were planted in Blackford County.[20] Total acreage for those two crops is 76,400. Blackford County is 165.4 square miles, which is 105,856 acres based on 640 acres per square mile. Acreage for the two crops (76,400) divided by acreage for the county (105,856) is 72.1 percent.

- ↑ Mileages from Blackford County to Fort Wayne and Indianapolis are based on highway miles using county seat Hartford City for Blackford County.[21]

- ↑ A portion of Shinn's description of the Renner Stock Farm has been reproduced on a web page (scroll down).[26]

- ↑ Jackson completed his second term as president in 1837, only one year before Blackford County was created, and two years before Blackford County was organized.[35]

- ↑ In the United States Census Bureau's American Fact Finder 2010, Use Quick Start, select "Hartford City city, Indiana" for geography, and "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010" for topic or table name. For Montpelier, select "Montpelier city, Indiana". For Dunkirk, select "Dunkirk city, Indiana"; and for Shamrock Lakes, select "Shamrock Lakes town, Indiana".[7]

- ↑ All five of Blackford County’s unincorporated communities are shown in UniversalMAP’s Northern Indiana road map, purchased in 2009, and Indiana's digital state transportation map for 2009–2010.[8]

- ↑ An 1876 Blackford County map in the David Rumsey Map Collection shows both Dorsey Station and Bowser Station.[43]

- ↑ "Blount" may have also been spelled "Blunt". In Bureau of Land Management records for the area that would become Blackford County, "John Blunt" is listed as a land purchaser in 1835. (Benjamin Reasoner is listed as the first land purchaser.)[51]

- ↑ At least three sources incorrectly say Blackford County began in 1837: Biographical and historical record of Jay and Blackford Counties...,[57] Montgomery and Jay,[54] and Shinn.[52]

- ↑ Multiple dates are designated as the time Blackford County was “created” or “founded”. February 15, 1838 is the date Blackford County was created by legislation, and this date is used by at least one source as the county’s creation date.[62] The original legislation expected the county to be organized on April 2, 1838. An additional act clarified the county’s status on January 29, 1839, and the county was finally organized later during that year.

- ↑ The railroad changed ownership and names more than once, and was also known as the Lake Erie and Western Railroad, the Nickel Plate Road, and the Norfolk and Western Railway. The line is currently owned by the Norfolk Southern Railway.[68]

- ↑ Hartford City's workforce became an attraction for glass companies. The city had a community of highly skilled glass workers from Belgium.[79]

- ↑ A second source says the American Window Glass plant closed in 1929 instead of 1932.[86]

- ↑ Grant's Overhead Door article in volume 70 of the International Directory of Company Histories has been reproduced on a web page.[91]

- ↑ In the United States Census Bureau's American Fact Finder 2010, Use Quick Start, select "Blackford County, Indiana" for geography, and "DP-3 Profile of Selected Economic Characteristics: 2000" for topic or table name.[99]

- ↑ In the United States Census Bureau's American Fact Finder 2010, Use Quick Start, select "Blackford County, Indiana" for geography, and "DP-2 Profile of Selected Social Characteristics: 2000" for topic or table name.[100]

- ↑ Blackford County's 165.4 square miles multiplied by 640 acres per square mile is 105,856 acres (42,838 ha).[116] The county's farmland totals to 84,626 acres (34,247 ha).[123] The amount of farmland divided by the county's total of 105,856 acres (42,838 ha) is 79.94 percent.

- ↑ Examples of Johnson's patents are United States Patent No. 1,784,292,[164] United States Patent No. 1,824,212,[165] and United States Patent No. 2,026,091.[166]

- References

- ↑ "Origin of Indiana County Names". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "A Biography of Isaac Newton Blackford". Blackford County Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- 1 2 "Find A County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ↑ STATS Indiana. "Blackford County Townships". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University Kelly School of Business. Retrieved 2011-09-20.

- 1 2 "Census 2010 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Counties". United States Census. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- 1 2 3 "Blackford County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- 1 2 3 "Indiana Transportation Map 2009–2010" (PDF). Indiana Department of Transportation. 2009. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- 1 2 "State of Indiana 2011 Rail System Map" (PDF). Indiana Department of Transportation. 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 114

- ↑ Shinn 1900, p. 222

- ↑ Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana 2005, p. 77

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 17–18

- 1 2 Forstall 1996, pp. 50–53

- 1 2 Hamilton, Abraham & Lankford 2005, p. 1 section 7

- ↑ Leonard & Walker 2005, p. 5 section 8

- 1 2 Davis, Scott (2002-12-01). "East Central Indiana's Glass legacy". The Star Press (Muncie, Indiana). p. 4A.

- 1 2 "What's Wrong At Sneath?". Hartford City News Times. 1952-10-02. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Grant 2005, pp. 214–215

- ↑ "National Agricultural Statistics Service County Level Data". U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ "MapQuest (search for Hartford City, Indiana)". MapQuest. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ "Indiana County Map". Census Finder – A Directory of Free Census Records. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 10

- 1 2 Shinn 1914, p. 36

- ↑ "Renner Stock Farm". Deb Murray. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Garrigus 1990, p. 13

- ↑ Shinn 1900, p. 235

- 1 2 3 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 146

- ↑ United States Geological Survey. "Geographic Names Information System: Lakes in Blackford County, Indiana". Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 123

- ↑ Shinn 1900, p. 226

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 152

- ↑ Shinn 1900, p. 227

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 126

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 16

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 90

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 130

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.), p. 1

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey. "Geographic Names Information System: Populated places in Blackford County, Indiana". Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 17

- 1 2 3 "A Postoffice is Wiped Out". Hartford City Evening News. 1907-02-07. p. 1.

- 1 2 "David Rumsey Map Collection". Map of Blackford County (with) Montpelier, Hartford City. Andreas, A. T. (Alfred Theodore), 1839–1900; Baskin, Forster and Company, 1876. Cartography Associates. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 157

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 117

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 155–156

- 1 2 Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, p. 715

- ↑ "Godfroy Reserve". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Beeson, p. 1

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 141

- 1 2 "Blackford County, Indiana, Land Records 1831–1837". Genealogy Trails History Group. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- 1 2 Shinn 1900, p. 224

- 1 2 Beeson & Bonham 1974, p. 4

- 1 2 Montgomery & Jay 1922, p. 84

- ↑ Indiana State House of Representatives 1836, p. 118

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 91

- ↑ Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, p. 724

- ↑ Indiana State House of Representatives 1837, p. 346

- 1 2 Indiana General Assembly 1839, pp. 64–65 (Chapter XLIX)

- ↑ Shockley 1914, p. 38

- ↑ Monks, Esarey & Shockley 1916, pp. 564–565

- ↑ Kane & Aiken 2005, p. 361

- ↑ Shockley 1914, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 14

- ↑ Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, p. 744

- 1 2 3 4 Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, pp. 759–760

- ↑ Goltra 1895, p. 14

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, pp. 759–760, 239–240

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 19

- ↑ "Norfolk Southern Railway Company—Abandonment Exemption—in Blackford County, IN". Surface Transportation Board. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Indiana's Natural Gas Boom". The American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources 1897, pp. 71–72

- ↑ "GREAT INDIANA OIL STRIKE.; Well in Blackford County Field Surpasses the Famous Texas Gusher". The New York Times. 1901-02-12. p. 1 Special.

- ↑ Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources 1896, p. 405

- ↑ Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, p. 761

- 1 2 Indiana Department of Inspection 1902, pp. 57 & 91

- ↑ Dale 1902, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 48

- ↑ Beetem 1980, p. 1 section 7

- ↑ Indiana State Board of Health 1907, p. 250

- ↑ Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana 2005, pp. 59–63

- ↑ Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana 2005, pp. 42–45

- ↑ Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 91

- ↑ "Human Blowers Thing of the Past – Machines Replacing Skilled Trades and Obsolete Methods of Manufacture of Window Glass". Daily Times Gazette (Hartford City, Indiana). 1908-04-13. p. 1.

By June 1 three fourths of the window glass plants now operating by the obsolete way with human blowers will be out of blast and by July all will be idle, many never to resume by the old plan.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 89

- ↑ "Millgrove Plant is to Move to Albany?". The Telegram (Hartford City, IN). 1911-01-11. p. 4.

- 1 2 McIlwraith & Muller 2001, p. 336

- 1 2 3 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 86

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 88

- ↑ "Overhead Door Corporation" (PDF). CBS Interactive Business Network Resource Library. 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ "Plastics Plant to Close, Idling 200". McGraw-Hill Broadcasting Company. 2011-01-28. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ Belz, Adam (2011-06-01). "Farm boom leaves Main Street wanting". USA Today. p. 6A.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Profile of Selected Economic Characteristics: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ↑ "Profile of Selected Social Characteristics: 2000". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- 1 2 Indiana Code. "Title 36, Article 2, Section 3". Government of Indiana. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Indiana Code. "Title 2, Article 10, Section 2" (PDF). Government of Indiana. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ State of Indiana Department of Local Government Finance. "2010 Budget Order (Blackford County, Indiana)" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ "County Government Departments and Offices". Blackford County. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Duties". United Township Association of Indiana. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ "Government". United Township Association of Indiana. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ "Indiana Senate Districts". State of Indiana. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ "Indiana House Districts". State of Indiana. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- 1 2 "Monthly Averages for Hartford City, Indiana". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ "Köppen Climate Classification for the Conterminous United States". Idaho State Climate Services. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "Climate fact sheet". Indiana State Climate Office. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ↑ "The Palm Sunday Story April 11, 1965 — Indiana and Michigan". National Weather Service – Northern Indiana. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

The tornado steamed across farmland near Roll, and then struck Keystone with F4 strength, killing two people. It continued to the northeast and hit Linn Grove, causing two more fatalities.

- ↑ "Map of tornadoes in Blackford County" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "Indiana virtually paralyzed". Hartford City News-Times. 1978-01-26. p. 1.

Downtown Hartford City looked like a virtual Ghost Town as blizzard conditions made it almost impossible for vehicles other than snow–mobiles to travel the highways.

- ↑ "Death, power shortages, inconvenience hamper County". Hartford City News-Times. 1978-01-27. p. 1.

Last night even four wheel drive vehicles found the going rough as intense winds, sometimes gusting up to 45 mph, caused drifting snow to block highways and impede travel.

- 1 2 3 4 STATS Indiana. "InDepth Profile: Blackford County, Indiana". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University Kelly School of Business. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ↑ "Blackford Industrial Park". Blackford County Economic Development Corporation. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "Montpelier Industrial Park". Blackford County Economic Development Corporation. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- 1 2 3 4 "Blackford County Employers". Blackford County Economic Development Corporation. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 108

- ↑ STATS Indiana. "InDepth Profile: Delaware County, Indiana". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University Kelly School of Business. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ STATS Indiana. "InDepth Profile: Grant County, Indiana". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University Kelly School of Business. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- 1 2 3 United States Department of Agriculture. "2007 Census of Agriculture, County Profile, Blackford County Indiana" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "State Road 3". Highway Explorer. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "State Road 18". Highway Explorer. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "State Road 26". Highway Explorer. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "State Road 167". Highway Explorer. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Norfolk Southern Railway Company — Abandonment Exemption — in Blackford County, IN". Surface Transportation Board. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "Central Railroad Company of Indianapolis — Lease and Operation Exemption — Norfolk Southern Railway Company". Surface Transportation Board. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "Central Railroad of Indianapolis". RailAmerica. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Blackford County Schools". Blackford County School Corporation. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ↑ "Blackford County Schools — Overview". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 28

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 28–29

- ↑ "Blackford High School — Overview". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- ↑ "Indiana Education Data for Blackford Junior High School". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Indiana Education Data for Montpelier School". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Indiana Education Data for Southside Elementary School". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Indiana Education Data for Northside Elementary School". Indiana Department of Education. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Ball State University – About – Visit the Campus". Ball State University. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- ↑ "Ivy Tech Community College – East Central". Ivy Tech Community College. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- ↑ "Indiana Wesleyan University – About Us". Indiana Wesleyan University. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- ↑ "Taylor University – Area Info – Maps and Directions". Taylor University. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ↑ Leonard & Walker 2005, p. 6 section 8

- ↑ "Announcements and actions on properties for the National Register of Historic Places, July 6, 2007". New listings. National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Hartford City Public Library". Hartford City Public Library. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ↑ "Blackford County Historical Society". Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ "Blackford County Health Department". Blackford County. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "History of IU Health Blackford". Indiana University Health. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 51

- ↑ Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) 1887, pp. 734–735

- ↑ "Hartford City News-Times Centennial Tabloid". Hartford City Evening News. 1985-12-30. p. 6.

- ↑ "Hartford City News-Times". Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ↑ "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47: Telecommunication". United State Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ↑ "TV Query Results". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ↑ "AM Query Results". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ↑ "FM Query Results". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ↑ "Station Search Details – WMXQ". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ↑ "Station Search Details – WJCO". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- ↑ "Rural High Speed Internet Expands". Blackford County. 2010-04-14. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

While OIBW already offered wireless service in Hartford City and Montpelier, the addition of antenna sites at the Blackford County Security Center and the Highway Department brings in even larger areas of Harrison and Jackson townships.

- 1 2 "Biographical Data, Kevin A. Ford (Colonel, USAF, Ret.), NASA Astronaut". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Space shuttle Discovery launched after days of delays". Reuters. 2009-08-29. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Russian spacecraft with US-Russian crew blasts off to orbiting space station". Fox News Network. 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ US patent 1,784,292, "Double Overhead Door", issued 1930–12–09

- ↑ US patent 1,824,212, "Movable Sealing Strip for Doors", issued 1931–09–22

- ↑ US patent 2,026,291, "Multiple Door Construction", issued 1935–12–31, assigned to Overhead Door Corporation

- ↑ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 87

- 1 2 Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 39–40

- ↑ "Indiana Governor Maurice Clifford Townsend (1884–1954)". IN.gov, Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- 1 2 Hammel & Klingelhoffer 1999, p. 212

- ↑ "Hall of Fame Induction 2006 – Spotlight on Erika Wicoff". CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- Cited works

- Beetem, Debra (1980). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Blackford County Courthouse" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places (National Park Service). Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Beeson, Cecil E. "Blackford County History". Blackford County Historical Society.

- Beeson, Cecil E.; Bonham, John A. (1974). ’76 and Blackford County, Indiana. Fort Wayne, Indiana: Fort Wayne Public Library. OCLC 3402347.

- Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.). "Ghost Towns in Blackford County, Indiana". Blackford County Historical Society.

- Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) (1986). A History of Blackford County, Indiana : with historical accounts of the county, 1838–1986 [and] histories of families who have lived in the county. Hartford City, Indiana: Blackford County Historical Society. OCLC 15144953.

- Dale, George R. (1902). Directory of Hartford City, Indiana, Together with a Complete Gazetteer of Blackford County Land Owners. Troy, Ohio: George R. Dale. ISBN 978-1-153-46853-4.

- Forstall, Richard L. (editor) (1996). Population of states and counties of the United States: 1790 to 1990 from the twenty-one decennial censuses. United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Population Division. ISBN 0-934213-48-8. OCLC 34927951.

- Garrigus, Andrew (1990). Engineering Soils Map of Blackford County, Indiana. West Lafayette, Indiana: Joint Highway Research Project, Indiana Department of Transportation and Purdue University. OCLC 23770990. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Glass, James A.; Kohrman, David (2005). The Gas Boom of East Central Indiana. Image of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-3963-8. OCLC 61885891. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Goltra, W. F. (1895). Characteristics of the Lake Erie & Western Railroad System. Indianapolis: Press of Levey Bros. & Company. OCLC 7147894. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Grant, Tina (2005). International directory of company histories, Volume 70. Chicago: St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-545-7. OCLC 224417874. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Hamilton, Kristi; Abraham, Kent; Lankford, Susan (2005). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Hartford City Courthouse Square District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places (National Park Service). Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Hammel, Bob; Klingelhoffer, Kit (1999). The Glory of Old IU: Indiana University. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Pub. ISBN 978-1-58261-068-9. OCLC 42939082. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana (2005). Blackford County: Interim Report, Indiana Historic Sites and Structures Inventory. Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana. ISBN 978-1-889235-20-2. OCLC 62513317. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources (1896). "Annual Report (1895)" 20. Indianapolis: Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources. OCLC 7536715.

- Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources (1897). "Annual Report (1896)" 21. Indianapolis: Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources. OCLC 7536715.

- Indiana Department of Inspection (1902). "Annual report of the Department of Inspection of manufacturing and mercantile establishments, laundries, bakeries, quarries, printing offices and public buildings" (1901). Indianapolis: Indiana Department of Inspection. OCLC 13018369.

- Indiana General Assembly (1839). "Laws of the state of Indiana, passed at the ... session of the General Assembly". 23rd session. Indianapolis: J.P. Chapman. OCLC 8733001.

- Indiana State Board of Health (1907). "Annual Report of the State Board of Health of Indiana" 26. Indianapolis: Indiana State Board of Health. OCLC 7567509.

- Indiana State House of Representatives (1836). "Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Indiana during the Twenty-First Session of the General Assembly". Indianapolis: M. M. Henkle.

- Indiana State House of Representatives (1837). "Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Indiana during the Twenty-Second Session of the General Assembly". Indianapolis: Bolton and Livingston. OCLC 561680396.

- Kane, Joseph Nathan; Aiken, Charles Curry (2005). The American counties : origins of county names, dates of creation and population data, 1950–2000. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5036-1. OCLC 260010945. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Leonard, Craig; Walker, Amy (2005). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Montpelier Carnegie Library" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places (National Park Service). Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- McIlwraith, Thomas F.; Muller, Edward K. (2001). North America: the Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-0018-1. OCLC 248646178. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Monks, Leander John; Esarey, Logan; Shockley, Ernest V. (1916). Courts and Lawyers of Indiana. Indianapolis: Federal Publishing Company. OCLC 4158945. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Montgomery, M. W.; Jay, Milton T. (1922). History of Jay County, Indiana : including its World War record and incorporating the Montgomery history. Indianapolis: Historical Publishing Company. OCLC 5976187. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Shinn, Benjamin Granville (1900). Biographical memoirs of Blackford County, Ind: to which is appended a comprehensive compendium of national biography ... embellished with portraits of many well known residents of Blackford County, Indiana. Chicago: The Bowen Publishing Company. OCLC 3554406.

- Shinn, Benjamin Granville (1914). Blackford and Grant Counties, Indiana: A Chronicle of Their People Past and Present with Family Lineage and Personal Memoirs: Volume I. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-178-13953-2. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- Shockley, E. V. (1914). "County Seats and County Seat Wars of Indiana". Indiana Magazine of History (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Department of History) X (1). OCLC 2371402.

- Unlisted (Biographical and historical record...) (1887). Biographical and historical record of Jay and Blackford Counties, Indiana: Containing ... portraits and biographies of some of the prominent men of the state : engravings of prominent citizens in Jay and Blackford Counties, with personal histories of many of the leading families and a concise history of Jay and Blackford Counties and their cities and villages. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company. OCLC 15560416. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blackford County, Indiana. |

- Blackford County official website

- Blackford County Historical Society

- Indiana County History (Blackford)

|

Wells County |  | ||

| Grant County | |

Jay County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Delaware County |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 40°28′N 85°19′W / 40.47°N 85.32°W