Birmingham

| Birmingham | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City and Metropolitan borough | ||||||||

Clockwise, from top: skyline of Birmingham City Centre from the south; Birmingham Town Hall; St Martin's church and Selfridges department store in the Bull Ring; the University of Birmingham; St Philip's Cathedral; the Library of Birmingham. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Etymology: Old English Beormingahām (home or settlement of the Beormingas) | ||||||||

|

Nickname(s):

| ||||||||

| Motto: Forward | ||||||||

Birmingham shown within the West Midlands county | ||||||||

Birmingham Location within the United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Coordinates: 52°28′59″N 1°53′37″W / 52.48306°N 1.89361°WCoordinates: 52°28′59″N 1°53′37″W / 52.48306°N 1.89361°W | ||||||||

| Sovereign state |

| |||||||

| Constituent country |

| |||||||

| Region | West Midlands | |||||||

| Ceremonial county |

| |||||||

| Historic county |

| |||||||

| Settlement | c. 600 | |||||||

| Seigneurial borough | 1166 | |||||||

| Municipal borough | 1838 | |||||||

| City | 1889 | |||||||

| Metropolitan borough | 1 April 1974 | |||||||

| Administrative HQ |

The Council House, Victoria Square | |||||||

| Government | ||||||||

| • Type | Metropolitan borough | |||||||

| • Body | Birmingham City Council | |||||||

| • Lord Mayor | Ray Hassell (Lib) | |||||||

| • Council Control | Labour | |||||||

| • Council Leader | John Clancy (L) | |||||||

| • MPs | ||||||||

| Area | ||||||||

| • City | 103.39 sq mi (267.77 km2) | |||||||

| • Urban | 231.2 sq mi (598.9 km2) | |||||||

| Elevation | 460 ft (140 m) | |||||||

| Population (2015 mid year estimate.) | ||||||||

| • City | 1,101,360<ref name=""ONS 2014 Mid-Year Population Estimate ">"UK Population Estimates". ONS. Retrieved 28 June 2014</ref> | |||||||

| • Rank | 1st, English districts | |||||||

| • Density | 10,620/sq mi (4,102/km2) | |||||||

| • Urban | 2,440,986 (3rd) | |||||||

| • Metro | 3,701,107 (2nd) | |||||||

| Demonym(s) | Brummie | |||||||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC+0) | |||||||

| • Summer (DST) | BST (UTC+1) | |||||||

| Postcode | B | |||||||

| Area code(s) | 0121 | |||||||

| ISO 3166 code | GB-BIR | |||||||

| Ethnicity (2011 Census) [1] |

| |||||||

| Primary Airport | Birmingham Airport | |||||||

| GDP | US$ 121.1 billion [2] (2nd) | |||||||

| GDP per capita | US$ 31,572[2] | |||||||

| Website | Birmingham City | |||||||

Birmingham (![]() i/ˈbɜːrmɪŋəm/) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands, England. It is the largest and most populous British city outside London with 1,101,360 residents (2014 est.),[3] and its population increase of 88,400 residents between the 2001 and 2011 censuses was greater than that of any other British local authority.[4] The city lies within the West Midlands Built-up Area, the third most populous built-up area in the United Kingdom with 2,440,986 residents (2011 census),[5] and its metropolitan area is the United Kingdom's second most populous with 3,701,107 residents (2012 est.) and is also the 9th largest metropolitan area in Europe.[6]

i/ˈbɜːrmɪŋəm/) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands, England. It is the largest and most populous British city outside London with 1,101,360 residents (2014 est.),[3] and its population increase of 88,400 residents between the 2001 and 2011 censuses was greater than that of any other British local authority.[4] The city lies within the West Midlands Built-up Area, the third most populous built-up area in the United Kingdom with 2,440,986 residents (2011 census),[5] and its metropolitan area is the United Kingdom's second most populous with 3,701,107 residents (2012 est.) and is also the 9th largest metropolitan area in Europe.[6]

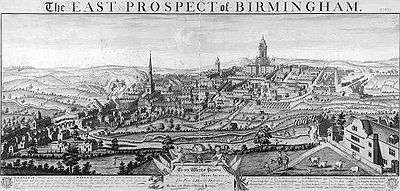

A medium-sized market town during the medieval period, Birmingham grew to international prominence in the 18th century at the heart of the Midlands Enlightenment and subsequent Industrial Revolution, which saw the town at the forefront of worldwide advances in science, technology and economic development, producing a series of innovations that laid many of the foundations of modern industrial society.[7] By 1791 it was being hailed as "the first manufacturing town in the world".[8] Birmingham's distinctive economic profile, with thousands of small workshops practising a wide variety of specialised and highly skilled trades, encouraged exceptional levels of creativity and innovation and provided a diverse and resilient economic base for industrial prosperity that was to last into the final quarter of the 20th century. Perhaps the most important invention in British history, the industrial steam engine, was invented in Birmingham.[9] Its resulting high level of social mobility also fostered a culture of broad-based political radicalism, that under leaders from Thomas Attwood to Joseph Chamberlain was to give it a political influence unparalleled in Britain outside London, and a pivotal role in the development of British democracy.[10] From the summer of 1940 to the spring of 1943, Birmingham was bombed heavily by the German Luftwaffe in what is known as the Birmingham Blitz. The damage done to the city's infrastructure, in addition to a deliberate policy of demolition and new building by planners, led to extensive demolition and redevelopment in subsequent decades.

Today Birmingham's economy is dominated by the service sector.[11] The city is a major international commercial centre, ranked as a beta− world city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network;[12] and an important transport, retail, events and conference hub. Its metropolitan economy is the second largest in the United Kingdom with a GDP of $121.1bn (2014),[2] and its six universities make it the largest centre of higher education in the country outside London.[13] Birmingham's major cultural institutions – including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Birmingham Royal Ballet, the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, the Library of Birmingham and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts – enjoy international reputations,[14] and the city has vibrant and influential grassroots art, music, literary and culinary scenes.[15] Birmingham is the fourth-most visited city in the UK by foreign visitors.[16]

Birmingham's sporting heritage can be felt worldwide, with the concept of the Football League and lawn tennis both originating from the city.

People from Birmingham are called Brummies, a term derived from the city's nickname of Brum. This originates from the city's dialect name, Brummagem,[17] which may in turn have been derived from one of the city's earlier names, Bromwicham.[18] There is a distinctive Brummie accent and dialect.

History

Pre-history and medieval

Birmingham's early history is that of a remote and marginal area. The main centres of population, power and wealth in the pre-industrial English Midlands lay in the fertile and accessible river valleys of the Trent, the Severn and the Avon. The area of modern Birmingham lay in between, on the upland Birmingham Plateau and within the densely wooded and sparsely populated Forest of Arden.[19]

There is evidence of early human activity in the Birmingham area dating back 10,000 years,[20] with stone age artefacts suggesting seasonal settlements, overnight hunting parties and woodland activities such as tree felling.[21] The many burnt mounds that can still be seen around the city indicate that modern humans first intensively settled and cultivated the area during the bronze age, when a substantial but short-lived influx of population occurred between 1700 BC and 1000 BC, possibly caused by conflict or immigration in the surrounding area.[22] During the 1st-century Roman conquest of Britain, the forested country of the Birmingham Plateau formed a barrier to the advancing Roman legions,[23] who built the large Metchley Fort in the area of modern-day Edgbaston in AD 48,[24] and made it the focus of a network of Roman roads.[25]

Birmingham as a settlement dates from the Anglo-Saxon era. The city's name comes from the Old English Beormingahām, meaning the home or settlement of the Beormingas – indicating that Birmingham was established in the 6th or early 7th century as the primary settlement of an Anglian tribal grouping and regio of that name.[26] Despite this early importance, by the time of the Domesday Book of 1086 the manor of Birmingham was one of the poorest and least populated in Warwickshire, valued at only 20 shillings,[27] with the area of the modern city divided between the counties of Warwickshire, Staffordshire and Worcestershire.[28]

The development of Birmingham into a significant urban and commercial centre began in 1166, when the Lord of the Manor Peter de Bermingham obtained a charter to hold a market at his castle, and followed this with the creation of a planned market town and seigneurial borough within his demesne or manorial estate, around the site that became the Bull Ring.[29] This established Birmingham as the primary commercial centre for the Birmingham Plateau at a time when the area's economy was expanding rapidly, with population growth nationally leading to the clearance, cultivation and settlement of previously marginal land.[30] Within a century of the charter Birmingham had grown into a prosperous urban centre of merchants and craftsmen.[31] By 1327 it was the third-largest town in Warwickshire,[32] a position it would retain for the next 200 years.[33]

Early modern

The principal governing institutions of medieval Birmingham – including the Guild of the Holy Cross and the lordship of the de Birmingham family – collapsed between 1536 and 1547,[34] leaving the town with an unusually high degree of social and economic freedom and initiating a period of transition and growth.[35] By 1700 Birmingham's population had increased fifteenfold and the town was the fifth-largest in England and Wales.[36]

The importance of the manufacture of iron goods to Birmingham's economy was recognised as early as 1538, and grew rapidly as the century progressed.[37] Equally significant was the town's emerging role as a centre for the iron merchants who organised finance, supplied raw materials and traded and marketed the industry's products.[38] By the 1600s Birmingham formed the commercial hub of a network of forges and furnaces stretching from South Wales to Cheshire[39] and its merchants were selling finished manufactured goods as far afield as the West Indies.[40] These trading links gave Birmingham's metalworkers access to much wider markets, allowing them to diversify away from lower-skilled trades producing basic goods for local sale, towards a broader range of specialist, higher-skilled and more lucrative activities.[41]

By the time of the English Civil War Birmingham's booming economy, its expanding population, and its resulting high levels of social mobility and cultural pluralism, had seen it develop new social structures very different from those of more established areas.[42] Relationships were built around pragmatic commercial linkages rather than the rigid paternalism and deference of feudal society, and loyalties to the traditional hierarchies of the established church and aristocracy were weak.[42] The town's reputation for political radicalism and its strongly Parliamentarian sympathies saw it attacked by Royalist forces in the Battle of Birmingham in 1643,[43] and it developed into a centre of Puritanism in the 1630s[42] and as a haven for Nonconformists from the 1660s.[44]

The 18th century saw this tradition of free-thinking and collaboration blossom into the cultural phenomenon now known as the Midlands Enlightenment.[45] The town developed into a notable centre of literary, musical, artistic and theatrical activity;[46] and its leading citizens – particularly the members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham – became influential participants in the circulation of philosophical and scientific ideas among Europe's intellectual elite.[47] The close relationship between Enlightenment Birmingham's leading thinkers and its major manufacturers[48] – in men like Matthew Boulton and James Keir they were often in fact the same people[49] – made it particularly important for the exchange of knowledge between pure science and the practical world of manufacturing and technology.[50] This created a "chain reaction of innovation",[51] forming a pivotal link between the earlier Scientific Revolution and the Industrial Revolution that would follow.[52]

Industrial Revolution

Birmingham's explosive industrial expansion started earlier than that of the textile-manufacturing towns of the North of England,[53] and was driven by different factors. Instead of the economies of scale of a low-paid, unskilled workforce producing a single bulk commodity such as cotton or wool in large, mechanised units of production, Birmingham's industrial development was built on the adaptability and creativity of a highly paid workforce with a strong division of labour, practising a broad variety of skilled specialist trades and producing a constantly diversifying range of products, in a highly entrepreneurial economy of small, often self-owned workshops.[54] This led to exceptional levels of inventiveness: between 1760 and 1850 – the core years of the Industrial Revolution – Birmingham residents registered over three times as many patents as those of any other British town or city.[55]

The demand for capital to feed rapid economic expansion also saw Birmingham grow into a major financial centre with extensive international connections.[56] Lloyds Bank was founded in the town in 1765,[57] and Ketley's Building Society, the world's first building society, in 1775.[58] By 1800 the West Midlands had more banking offices per head than any other region in Britain, including London.[56]

Innovation in 18th-century Birmingham often took the form of incremental series of small-scale improvements to existing products or processes,[59] but also included major developments that lay at the heart of the emergence of industrial society.[7] In 1709 the Birmingham-trained Abraham Darby I moved to Coalbrookdale in Shropshire and built the first blast furnace to successfully smelt iron ore with coke, transforming the quality, volume and scale on which it was possible to produce cast iron.[60] In 1732 Lewis Paul and John Wyatt invented roller spinning, the "one novel idea of the first importance" in the development of the mechanised cotton industry.[61] In 1741 they opened the world's first cotton mill in Birmingham's Upper Priory.[62] In 1746 John Roebuck invented the lead chamber process, enabling the large-scale manufacture of sulphuric acid,[63] and in 1780 James Keir developed a process for the bulk manufacture of alkali,[64] together marking the birth of the modern chemical industry.[65] In 1765 Matthew Boulton opened the Soho Manufactory, pioneering the combination and mechanisation under one roof of previously separate manufacturing activities through a system known as "rational manufacture".[66] As the largest manufacturing unit in Europe this come to symbolise the emergence of the factory system.[67]

Most significant, however, was the development in 1776 of the industrial steam engine by James Watt and Matthew Boulton.[68] Freeing for the first time the manufacturing capacity of human society from the limited availability of hand, water and animal power, this was arguably the pivotal moment of the entire industrial revolution and a key factor in the worldwide increases in productivity that would follow over the following century.[69]

Regency and Victorian

Birmingham rose to national political prominence in the campaign for political reform in the early 19th century, with Thomas Attwood and the Birmingham Political Union bringing the country to the brink of civil war during the Days of May that preceded the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832.[70] The Union's meetings on Newhall Hill in 1831 and 1832 were the largest political assemblies Britain had ever seen.[71] Lord Durham, who drafted the Act, wrote that "the country owed Reform to Birmingham, and its salvation from revolution".[72] This reputation for having "shaken the fabric of privilege to its base" in 1832 led John Bright to make Birmingham the platform for his successful campaign for the Second Reform Act of 1867, which extended voting rights to the urban working class.[73]

Birmingham's tradition of innovation continued into the 19th century. Birmingham was the terminus for both of the world's first two long-distance railway lines: the 82 mile Grand Junction Railway of 1837 and the 112 mile London and Birmingham Railway of 1838.[74] Birmingham schoolteacher Rowland Hill invented the postage stamp and created the first modern universal postal system in 1839.[75] Alexander Parkes invented the first man-made plastic in the Jewellery Quarter in 1855.[76]

By the 1820s, an extensive canal system had been constructed, giving greater access to natural resources and fuel for industries. During the Victorian era, the population of Birmingham grew rapidly to well over half a million[77] and Birmingham became the second largest population centre in England. Birmingham was granted city status in 1889 by Queen Victoria.[78] Joseph Chamberlain, mayor of Birmingham and later an MP, and his son Neville Chamberlain, who was Lord Mayor of Birmingham and later the British Prime Minister, are two of the most well-known political figures who have lived in Birmingham. The city established its own university in 1900.[79]

20th century and contemporary

Birmingham suffered heavy bomb damage during World War II's "Birmingham Blitz". The city was also the scene of two scientific discoveries that were to prove critical to the outcome of the war.[80] Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls first described how a practical nuclear weapon could be constructed in the Frisch–Peierls memorandum of 1940,[81] the same year that the cavity magnetron, the key component of radar and later of microwave ovens, was invented by John Randall and Henry Boot.[82] Details of these two discoveries, together with an outline of the first jet engine invented by Frank Whittle in nearby Rugby, were taken to the United States by the Tizard Mission in September 1940, in a single black box later described by an official American historian as "the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores".[83]

The city was extensively redeveloped during the 1950s and 1960s.[84] This included the construction of large tower block estates, such as Castle Vale. The Bull Ring was reconstructed and New Street station was redeveloped. In the decades following World War II, the ethnic makeup of Birmingham changed significantly, as it received waves of immigration from the Commonwealth of Nations and beyond.[85] The city's population peaked in 1951 at 1,113,000 residents.[77]

Birmingham remained by far Britain's most prosperous provincial city as late as the 1970s,[86] with household incomes exceeding even those of London and the South East,[87] but its economic diversity and capacity for regeneration declined in the decades that followed World War II as Central Government sought to restrict the city's growth and disperse industry and population to the stagnating areas of Scotland, Wales and Northern England.[88] These measures hindered "the natural self-regeneration of businesses in Birmingham, leaving it top-heavy with the old and infirm",[89] and the city became increasingly dependent on the motor industry. The recession of the early 1980s saw Birmingham's economy collapse, with unprecedented levels of unemployment and outbreaks of social unrest in inner-city districts.[90]

In recent years, many parts of Birmingham has been transformed, with the redevelopment of the Bullring Shopping Centre[91] and regeneration of old industrial areas such as Brindleyplace, The Mailbox and the International Convention Centre. Old streets, buildings and canals have been restored, the pedestrian subways have been removed and the Inner Ring Road has been rationalised. In 1998 Birmingham hosted the 24th G8 summit.

Government

Birmingham City Council is the largest local authority in Europe with 120 councillors representing 40 wards.[92] Its headquarters are at the Council House in Victoria Square. As of 2014, the council has a Labour Party majority and is led by Sir Albert Bore, replacing the previous Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition at the May 2012 elections. The honour and dignity of a Lord Mayoralty was conferred on Birmingham by Letters Patent on 3 June 1896.

Birmingham's ten parliamentary constituencies are represented in the House of Commons as of 2015 by one Conservative and nine Labour MPs.[93] In the European Parliament the city forms part of the West Midlands European Parliament constituency, which elects six Members of the European Parliament.[94]

Birmingham was originally part of Warwickshire, but expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, absorbing parts of Worcestershire to the south and Staffordshire to the north and west. The city absorbed Sutton Coldfield in 1974 and became a metropolitan borough in the new West Midlands county. Until 1986, the West Midlands County Council was based in Birmingham City Centre.

Since 2011, Birmingham has formed part of the Greater Birmingham & Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership along with neighbouring authorities Bromsgrove, Cannock Chase, East Staffordshire, Lichfield, Redditch, Solihull, Tamworth, Wyre Forest.

A top-level government body, the West Midlands Combined Authority, will be formed in April 2016. The WMCA will gain devolved powers in transport, development planning, and economic growth. The authority will be governed by a directly-elected Mayor, similar to the Mayor of London.

Geography

Birmingham is located in the centre of the West Midlands region of England on the Birmingham Plateau – an area of relatively high ground, ranging between 500 and 1,000 feet (150–300 m) above sea level and crossed by Britain's main north-south watershed between the basins of the Rivers Severn and Trent. To the south west of the city lie the Lickey Hills,[95] Clent Hills and Walton Hill, which reach 1,033 feet (315 m) and have extensive views over the city. Birmingham is drained only by minor rivers and brooks, primarily the River Tame and its tributaries the Cole and the Rea.

The City of Birmingham forms a conurbation with the largely residential borough of Solihull to the south east, and with the city of Wolverhampton and the industrial towns of the Black Country to the north west, which form the West Midlands Built-up Area covering 59,972 ha (600 km2; 232 sq mi). Surrounding this is Birmingham's metropolitan area – the area to which it is closely economically tied through commuting – which includes the former Mercian capital of Tamworth and the cathedral city of Lichfield in Staffordshire to the north; the industrial city of Coventry and the Warwickshire towns of Nuneaton, Warwick and Leamington Spa to the east; and the Worcestershire towns of Redditch and Bromsgrove to the south west.[96]

Much of the area now occupied by the city was originally a northern reach of the ancient Forest of Arden, whose former presence can still be felt in the city's dense oak tree-cover and in the large number of districts such as Moseley, Saltley, Yardley, Stirchley and Hockley with names ending in "-ley": the Old English -lēah meaning "woodland clearing".[97]

Geology

Geologically, Birmingham is dominated by the Birmingham Fault which runs diagonally through the city from the Lickey Hills in the south west, passing through Edgbaston and the Bull Ring, to Erdington and Sutton Coldfield in the north east.[98] To the south and east of the fault the ground is largely softer Mercia Mudstone, interspersed with beds of Bunter pebbles and crossed by the valleys of the Rivers Tame, Rea and Cole and their tributaries.[99] To the north and west of the fault, between 150 and 600 feet (45–180 m) higher than the surrounding area and underlying much of the city centre, lies a long ridge of harder Keuper Sandstone.[100][101] The bedrock underlying Birmingham was mostly laid down during the Permian and Triassic periods.[98]

Climate

Birmingham has a temperate maritime climate, like much of the British Isles, with average maximum temperatures in summer (July) being around 21.3 °C (70.3 °F); and in winter (January) around 6.7 °C (44.1 °F).[102] Between 1971 and 2000 the warmest day of the year on average was 28.8 °C (83.8 °F)[103] and the coldest night typically fell to −9.0 °C (15.8 °F).[104] Some 11.2 days each year rose to a temperature of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or above[105] and 51.6 nights reported an air frost.[106] The highest recorded temperature, set during August 1990, was 34.9 °C (94.8 °F).[107]

Like most other large cities, Birmingham has a considerable urban heat island effect.[108] During the coldest night recorded, 14 January 1982, the temperature fell to −20.8 °C (−5.4 °F) at Birmingham Airport on the city's eastern edge, but just −12.9 °C (8.8 °F) at Edgbaston, near the city centre.[109]

Birmingham is a snowy city relative to other large UK conurbations, due to its inland location and comparatively high elevation.[109] Between 1961 and 1990 Birmingham Airport averaged 13.0 days of snow lying annually,[110] compared to 5.33 at London Heathrow.[111] Snow showers often pass through the city via the Cheshire gap on north westerly airstreams, but can also come off the North Sea from north easterly airstreams.[109]

Extreme weather is rare but the city has been known to experience tornados – the most recent being in July 2005 in the south of the city, damaging homes and businesses in the area.[112]

| Climate data for Birmingham Elmdon, 99m asl, 1971–2000, extremes 1901– (sunshine 1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

30.0 (86) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.9 (94.8) |

29.8 (85.6) |

26.8 (80.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

34.9 (94.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.8 (64) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.1 (34) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.0 (50) |

12.1 (53.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.8 (−5.4) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.2 (36) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−8.9 (16) |

−18.5 (−1.3) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73.2 (2.882) |

51.4 (2.024) |

55.8 (2.197) |

61.9 (2.437) |

61.3 (2.413) |

65.6 (2.583) |

63.8 (2.512) |

66.7 (2.626) |

68.1 (2.681) |

82.7 (3.256) |

74.8 (2.945) |

79.7 (3.138) |

805 (31.69) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 49.7 | 60.0 | 101.5 | 129.2 | 178.0 | 186.2 | 181.0 | 166.8 | 134.3 | 97.2 | 64.2 | 46.9 | 1,395 |

| Source #1: Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute[113] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration[114] | |||||||||||||

Environment

There are 571 parks within Birmingham[115] – more than any other European city[116] – totalling over 3,500 hectares (14 sq mi) of public open space.[115] The city has over six million trees,[116] and 250 miles of urban brooks and streams.[115] Sutton Park, which covers 2,400 acres (971 ha) in the north of the city,[117] is the largest urban park in Europe and a National Nature Reserve.[115] Birmingham Botanical Gardens, located close to the city centre, retains the regency landscape of its original design by J. C. Loudon in 1829,[118] while the Winterbourne Botanic Garden in Edgbaston reflects the more informal Arts and Crafts tastes of its Edwardian origins.[119]

Birmingham has many areas of wildlife that lie in both informal settings such as the Project Kingfisher and Woodgate Valley Country Park and in a selection of parks such as Lickey Hills Country Park, Handsworth Park, Kings Heath Park, and Cannon Hill Park; the latter also housing the Birmingham Nature Centre.[120]

Demography

The 2012 mid-year estimate for the population of Birmingham was 1,085,400. This was an increase of 11,200, or 1.0%, since the same time in 2011. Since 2001, the population has grown by 99,500, or 10.1%. Birmingham is the largest local Authority area and city outside London. The population density is 10,391 inhabitants per square mile (4,102/km²) compared to the 976.9 inhabitants per square mile (377.2/km²) for England. Based on the 2011 census, Birmingham's population is projected to reach 1,160,100 by 2021, an increase of 8.0%. This compares with an estimated rate of 9.1% for the previous decade.[122]

The West Midlands conurbation had a population of 2,441,00 (2011 est.,), and 2,762,700 people live in the West Midlands (county) (2012 est.,).

According to figures from the 2011 census, 57.9% of the population was White (53.1% White British, 2.1% White Irish, 2.7% Other White), 4.4% of mixed race (2.3% White and Black Caribbean, 0.3% White and Black African, 1.0% White and Asian, 0.8% Other Mixed), 26.6% Asian (13.5% Pakistani, 6.0% Indian, 3.0% Bangladeshi, 1.2% Chinese, 2.9% Other Asian), 8.9% Black (2.8% African, 4.4% Caribbean, 1.7% Other Black), 1.0% Arab and 1.0% of other ethnic heritage.[123] 57% of primary and 52% of secondary pupils are from non-white British families.[124]

238,313 Birmingham residents were born overseas, of these, 44% (103,682) have been resident in the UK for less than 10 years. Countries new to the twenty most reported countries of birth for Birmingham residents since 2001 include, Iran, Zimbabwe, Philippines and Nigeria. Established migrants outnumbered newer migrants in all wards except for, Edgbaston, Ladywood, Nechells and Selly Oak.

In Birmingham 60.4% of the population was aged between 16 and 74, compared to 66.7% in England as a whole.[125] There are generally more females than males in each single year of age, except for the youngest ages (0-18) and late 30's and late 50's. Females represented 51.6% of the population whilst men represented 48.4%. The differences are most marked in the oldest age group reflecting greater female longevity, where more women were 70 or over.[126] The bulge around the early 20's is due largely to students coming to the city's Universities. Children around age 10 are a relatively small group, reflecting the decline in birth rates around the turn of the century. There is a large group of children under the age of five which reflecting high numbers of births in recent years. Births are up 20% since 2001, increasing from 14,427 to 17,423 in 2011.

In 2011 of all households in Birmingham, 0.12% were same-sex civil partnership households, compared to the English national average of 0.16%.[127]

25.9% of all households owned their accommodation outright, another 29.3% owned their accommodation with a mortgage or loan. These figures were below the national average.[128]

45.5% of people said they were in very good health which was below the national average. Another 33.9% said they were in good health, which was also below the national average. 9.1% of people said their day-to-day activities were limited a lot by their health which was higher than the national average.[128]

The Birmingham Larger Urban Zone, a Eurostat measure of the functional city-region approximated to local government districts, has a population of 2,357,100 in 2004.[129] In addition to Birmingham itself, the LUZ includes the Metropolitan Boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull and Walsall, along with the districts of Lichfield, Tamworth, North Warwickshire and Bromsgrove.[130]

Religion

Christianity is the largest religion within Birmingham, with 46.1% of residents identifying as Christians in the 2011 Census.[131] The city's religious profile is highly diverse, however: outside London, Birmingham has the United Kingdom's largest Muslim, Sikh and Buddhist communities; its second largest Hindu community; and its seventh largest Jewish community.[131] Between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, the proportion of Christians in Birmingham decreased from 59.1% to 46.1%, while the proportion of Muslims increased from 14.3% to 21.8% and the proportion of people with no religious affiliation increased from 12.4% to 19.3%. All other religions remained proportionately similar.[132]

St Philip's Cathedral was upgraded from church status when the Anglican Diocese of Birmingham was created in 1905. There are two other cathedrals: St Chad's, seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Birmingham and the Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Dormition of the Mother of God and St Andrew. The Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Midlands is also based at Birmingham, with a cathedral under construction. The original parish church of Birmingham, St Martin in the Bull Ring, is Grade II* listed. A short distance from Five Ways the Birmingham Oratory was completed in 1910 on the site of Cardinal Newman's original foundation.

The oldest surviving synagogue in Birmingham is the 1825 Greek Revival Severn Street Synagogue, now a Freemasons' Lodge hall. It was replaced in 1856 by the Grade II* listed Singers Hill Synagogue. Birmingham Central Mosque, one of the largest in Europe, was constructed in the 1960s.[133] During the late 1990s Ghamkol Shariff Masjid was built in Small Heath.[134] The Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha Sikh Gurdwara was built on Soho Road in Handsworth in the late 1970s and the Buddhist Dhammatalaka Peace Pagoda near Edgbaston Reservoir in the 1990s. Winners' Chapel also maintains physical presence in Digbeth.

Economy

Birmingham grew to prominence as a manufacturing and engineering centre, but its economy today is dominated by the service sector, which in 2012 accounted for 88% of the city's employment.[11] Birmingham is the largest centre in Great Britain for employment in public administration, education and health;[136] and after Leeds the second largest centre outside London for employment in financial and other business services.[137] It is ranked as a beta- world city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network, the third highest ranking in the country after London and Manchester,[12] and its wider metropolitan economy is the second-largest in the United Kingdom with a GDP of $121.1bn (2014 est., PPP).[2] Two FTSE100 companies (Severn Trent and IMI plc, which is currently a FTSE250 company) have their corporate headquarters within Birmingham, with two more based in the wider metropolitan area, together forming the largest concentration outside London and the South East.[138] With major facilities such as the National Exhibition Centre and International Convention Centre Birmingham attracts 42% of the UK's total conference and exhibition trade.[139]

.jpg)

Manufacturing accounted for 8% of employment within Birmingham in 2012, a figure beneath the average for the UK as a whole.[11] Major industrial plants within the city include Jaguar Land Rover in Castle Bromwich and Cadbury in Bournville, with large local producers also supporting a supply chain of precision-based small manufacturers and craft industries.[140] More traditional industries also remain: 40% of the jewellery made in the UK is still produced by the 300 independent manufacturers of the city's Jewellery Quarter,[141] continuing a trade first recorded in Birmingham in 1308.[32]

| Year | GVA (£ million) | Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 21,015 | |

| 2009 | 20,646 | |

| 2010 | 21,557 | |

| 2011 | 22,230 | |

| 2012 | 22,708 | |

| 2013 | 24,067 | |

Birmingham's GVA was £24.1bn (2013 est.,), and the economy grew relatively slowly between 2002 and 2012, where growth was 30% below the national average.[143] The value of manufacturing output in the city declined by 21% in real terms between 1997 and 2010, but the value of financial and insurance activities more than doubled.[144] With 16,281 start-ups registered during 2013 Birmingham has the highest level of entrepreneurial activity outside London,[145] while the number of registered businesses in the city grew by 1.6% during 2012.[146] Birmingham was behind only London and Edinburgh for private sector job creation between 2010 and 2013.[147]

Economic inequality within Birmingham is greater than in any other major English city, and is exceeded only by Glasgow in the United Kingdom.[148] Levels of unemployment are among the highest in the country, with 14.4% of the economically active population unemployed (Dec 2013).[149] In the inner-city wards of Aston and Washwood Heath, the figure is higher than 30%. Two-fifths of Birmingham's population live in areas classified as in the 10% most deprived parts of England, and overall Birmingham is the most deprived local authority in England in terms of income and employment deprivation.[150] The city's infant mortality rate is high, around 60% worse than the national average.[151] Meanwhile, just 49% of women have jobs, compared to 65% nationally,[151] and only 28% of the working-age population in Birmingham have degree level qualifications in contrast to the average of 34% across other Core Cities.[152]

According to the 2014 Mercer Quality of Living Survey, Birmingham was placed 51st in the world in, which was the second highest rating in the UK. This is an improvement on the city's 56th place in 2008.[153] The Big City Plan aims to move the city into the index's top 20 by 2026.[154] An area of the city has been designated an enterprise zone, with tax relief and simplified planning to lure investment.[155]

Culture

Music

The internationally renowned City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra's home venue is Symphony Hall. Other notable professional orchestras based in the city include the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, the Royal Ballet Sinfonia and Ex Cathedra, a Baroque chamber choir and period instrument orchestra. The Orchestra of the Swan is the resident chamber orchestra at Birmingham Town Hall,[156] where weekly recitals have also been given by the City Organist since 1834.[157]

The Birmingham Triennial Music Festivals took place from 1784 to 1912. Music was specially composed, conducted or performed by Mendelssohn, Gounod, Sullivan, Dvořák, Bantock and Edward Elgar, who wrote four of his most famous choral pieces for Birmingham. Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius had its début performance there in 1900. Composers born in the city include Albert William Ketèlbey and Andrew Glover.

Jazz has been popular in the city since the 1920s,[158] and there are many regular festivals such as the Harmonic Festival, the Mostly Jazz Festival and the annual International Jazz Festival.

Birmingham's other city-centre music venues include The National Indoor Arena, which was opened in 1991, O2 Academy on Bristol Street, which opened in September 2009 replacing the O2 Academy in Dale End, The CBSO Centre, opened in 1997, HMV Institute in Digbeth and the Adrian Boult Hall at the Birmingham Conservatoire.

During the 1960s Birmingham was the home of a music scene comparable to that of Liverpool.[159] Although it produced no single band as big as The Beatles it was "a seething cauldron of musical activity", and the international success of groups such as The Move, The Spencer Davis Group, The Moody Blues, Traffic and the Electric Light Orchestra had a collective influence that stretched into the 1970s and beyond.[159] The city was the birthplace of heavy metal music,[160] with pioneering metal bands from the late 1960s and 1970s such as Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, and half of Led Zeppelin having come from Birmingham. The next decade saw the influential metal bands Napalm Death and Godflesh arise from the city. Birmingham was the birthplace of modern bhangra in the 1960s,[161] and by the 1980s had established itself as the global centre of bhangra culture,[162] which has grown into a global phenomenon embraced by members of the Indian diaspora worldwide from Los Angeles to Singapore.[161] The 1970s also saw the rise of reggae and ska in the city with such bands as Steel Pulse, UB40, Musical Youth, The Beat and Beshara, expounding racial unity with politically leftist lyrics and multiracial line-ups, mirroring social currents in Birmingham at that time.

Other popular bands from Birmingham include Duran Duran, Fine Young Cannibals, Ocean Colour Scene, The Streets, The Twang, Deluka and Dexys Midnight Runners. Musicians Jeff Lynne, Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Bill Ward, Geezer Butler, John Lodge, Roy Wood, Joan Armatrading, Toyah Willcox, Denny Laine, Sukshinder Shinda, Apache Indian, Steve Winwood, Jamelia, Fyfe Dangerfield and Laura Mvula all grew up in the city.

Since 2012 the Digbeth-based B-Town indie music scene has attracted widespread attention, led by bands such as Peace and Swim Deep, with the NME comparing Digbeth to London's Shoreditch, and The Independent writing that "Birmingham is fast becoming the best place in the UK to look to for the most exciting new music".[163]

Theatre and performing arts

Birmingham Repertory Theatre is Britain's longest-established producing theatre,[165] presenting a wide variety of work in its three auditoria on Centenary Square and touring nationally and internationally.[166] Other producing theatres in the city include the Blue Orange Theatre in the Jewellery Quarter; the Old Rep, home stage of the Birmingham Stage Company; and @ A. E. Harris, the base of the experimental Stan's Cafe theatre company, located within a working metal fabricators' factory. Touring theatre companies include the politically radical Banner Theatre, the Maverick Theatre Company and Kindle Theatre. The Alexandra Theatre and the Birmingham Hippodrome host large-scale touring productions, while professional drama is performed on a wide range of stages across the city, including the Crescent Theatre, the Custard Factory, the Old Joint Stock Theatre, the Drum in Aston and the mac in Cannon Hill Park.

The Birmingham Royal Ballet is one of the United Kingdom's five major ballet companies and one of three based outside London.[167] It is resident at the Birmingham Hippodrome and tours extensively nationally and internationally. The company's associated ballet school – Elmhurst School for Dance in Edgbaston – is the oldest vocational dance school in the country.[168]

The Birmingham Opera Company under artistic director Graham Vick has developed an international reputation for its avant-garde productions,[169] which often take place in factories, abandoned buildings and other found spaces around the city.[170] In 2010 it was described by The Guardian as "far and away the most powerful example that I've experienced in this country of how and why opera can still matter."[171] More conventional seasons by Welsh National Opera and other visiting opera companies take place regularly at the Birmingham Hippodrome.[172]

Literature

Literary figures associated with Birmingham include Samuel Johnson who stayed in Birmingham for a short period and was born in nearby Lichfield. Arthur Conan Doyle worked in the Aston area of Birmingham whilst poet Louis MacNeice lived in Birmingham for six years. It was whilst staying in Birmingham that American author Washington Irving produced several of his most famous literary works, such as Bracebridge Hall and The Humorists, A Medley which are based on Aston Hall.

The poet W. H. Auden grew up in the Harborne area of the city and during the 1930s formed the core of the Auden Group with Birmingham University lecturer Louis MacNeice. Other influential poets associated with Birmingham include Roi Kwabena, who was the city's sixth poet laureate,[173] and Benjamin Zephaniah, who was born in the city.

The author J. R. R. Tolkien was brought up in Birmingham, with many locations in the city such as Moseley bog, Sarehole Mill and Perrott's Folly supposedly being the inspiration for various scenes in The Lord of the Rings. The award winning political playwright David Edgar was born in Birmingham, and the science fiction author John Wyndham spent his early childhood in the Edgbaston area of the city, as did Dame Barbara Cartland.

Birmingham has a vibrant contemporary literary scene, with local authors including David Lodge, Jim Crace, Jonathan Coe, Joel Lane and Judith Cutler.[174] The city's leading contemporary literary publisher is the Tindal Street Press, whose authors include prize-winning novelists Catherine O'Flynn, Clare Morrall and Austin Clarke.[175]

Birmingham is the home of the UK's longest-established local science fiction group, launched in 1971 (although there were earlier incarnations in the 1940s and 1960s) and which organises the annual science fiction event Novacon.

Art and design

.jpg)

The Birmingham School of landscape artists emerged with Daniel Bond in the 1760s and was to last into the mid 19th century.[176] Its most important figure was David Cox, whose later works make him an important precursor of impressionism.[177] The influence of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists and the Birmingham School of Art made Birmingham an important centre of Victorian art, particularly within the Pre-Raphaelite and Arts and Crafts movements.[178] Major figures included the Pre-Raphaelite and symbolist Edward Burne-Jones; Walter Langley, the first of the Newlyn School painters;[179] and Joseph Southall, leader of the group of artists and craftsmen known as the Birmingham Group.

The Birmingham Surrealists were among the "harbingers of surrealism" in Britain in the 1930s and the movement's most active members in the 1940s,[180] while more abstract artists associated with the city included Lee Bank-born David Bomberg and CoBrA member William Gear. Birmingham artists were prominent in several post-war developments in art: Peter Phillips was among the central figures in the birth of Pop Art;[181] John Salt was the only major European figure among the pioneers of photo-realism;[182] and the BLK Art Group used painting, collage and multimedia to examine the politics and culture of Black British identity. Contemporary artists from the city include the Turner Prize winner Gillian Wearing and the Turner Prize shortlisted Richard Billingham, John Walker and Roger Hiorns.[183]

Birmingham's role as a manufacturing and printing centre has supported strong local traditions of graphic design and product design. Iconic works by Birmingham designers include the Baskerville font,[184] Ruskin Pottery,[185] the Acme Thunderer whistle,[186] the Art Deco branding of the Odeon Cinemas[187] and the Mini.[188]

Museums and galleries

Birmingham has two major public art collections. Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery is best known for its works by the Pre-Raphaelites, a collection "of outstanding importance".[189] It also holds a significant selection of old masters – including major works by Bellini, Rubens, Canaletto and Claude – and particularly strong collections of 17th-century Italian Baroque painting and English watercolours.[189] Its design holdings include Europe's pre-eminent collections of ceramics and fine metalwork.[189] The Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Edgbaston is one of the finest small art galleries in the world,[190] with a collection of exceptional quality representing Western art from the 13th century to the present day.[191]

Birmingham Museums Trust runs other museums in the city including Aston Hall, Blakesley Hall, the Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Soho House and Sarehole Mill. The Birmingham Back to Backs are the last surviving court of back-to-back houses in the city.[192] Cadbury World is a museum showing visitors the stages and steps of chocolate production and the history of chocolate and the company. The Ikon Gallery hosts displays of contemporary art, as does Eastside Projects.

Thinktank is Birmingham's main science museum, with a giant screen cinema, a planetarium and a collection that includes the Smethwick Engine, the world's oldest working steam engine.[193] Other science-based museums include the National Sea Life Centre in Brindleyplace, the Lapworth Museum of Geology at the University of Birmingham and the Centre of the Earth environmental education centre in Winson Green.

Nightlife and festivals

.jpg)

Nightlife in Birmingham is mainly concentrated along Broad Street and into Brindleyplace. Although in more recent years Broad St has lost its popularity due to the closing of several clubs, the Arcadian now has more popularity in terms of nightlife. Outside the Broad Street area are many stylish and underground venues. The Medicine Bar in the Custard Factory, hmv Institute, Rainbow Pub and Air are large clubs and bars in Digbeth. Around the Chinese Quarter are areas such as the Arcadian and Hurst Street Gay Village, that abound with bars and clubs. Summer Row, The Mailbox, O2 Academy in Bristol Street, Snobs Nightclub, St Philips/Colmore Row, St Paul's Square and the Jewellery Quarter all have a vibrant night life. There are a number of late night pubs in the Irish Quarter.[194] Outside the city centre is Star City entertainment complex on the former site of Nechells Power Station.[195]

Birmingham is home to many national, religious and spiritual festivals including a St. George's Day party. The Birmingham Tattoo is a long-standing military show held annually at the National Indoor Arena. The Caribbean-style Birmingham International Carnival takes place in odd numbered years. Birmingham Pride takes place in the gay village and attracts up to 100,000 visitors each year. From 1997 until December 2006, the city hosted an annual arts festival ArtsFest, the largest free arts festival in the UK at the time.[196] The city's largest single-day event is its St. Patrick's Day parade (Europe's second largest, after Dublin).[197] Other multicultural events include the Bangla Mela and the Vaisakhi Mela. The Birmingham Heritage Festival is a Mardi Gras style event in August. Caribbean and African culture are celebrated with parades and street performances by buskers.

Other festivals in the city include the Birmingham International Jazz Festival,"Party in the Park"[198] was originally a festival hosted by local and regional radio stations which died down in 2007 and has now been brought back to life as an unsigned festival for regional unsigned acts to showcase themselves in a one-day music festival for the whole family. Birmingham Comedy Festival (since 2001; 10 days in October), which has been headlined by such acts as Peter Kay, The Fast Show, Jimmy Carr, Lee Evans and Lenny Henry, and the Off The Cuff Festival established in 2009. The biennial International Dance Festival Birmingham started in 2008, organised by DanceXchange and involving indoor and outdoor venues across the city. Since 2001, Birmingham has also been host to the Frankfurt Christmas Market. Modelled on its German counterpart, it has grown to become the UK's largest outdoor Christmas market and is the largest German market outside of Germany and Austria,[199] attracting over 3.1 million visitors in 2010[200] and over 5 million visitors in 2011.[201]

Entertainment and Leisure

Birmingham is home to many entainment and leisure venues. It is home to Europe's largest leisure and entertainment complex Star City as well as Europe's first out-of-city-centre entertainment and leisure complex Resorts World Birmingham owned by the Genting Group. The Mailbox which caters for more affluent clients is based within the city.

Architecture

.jpg)

Birmingham is chiefly a product of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries; its growth began during the Industrial Revolution. Consequently, relatively few buildings survive from its earlier history and those that do are protected. There are 1,946 listed buildings in Birmingham and thirteen scheduled ancient monuments.[202] Birmingham City Council also operate a locally listing scheme for buildings that do not fully meet the criteria for statutorily listed status.

Traces of medieval Birmingham can be seen in the oldest churches, notably the original parish church, St Martin in the Bull Ring. A few other buildings from the medieval and Tudor periods survive, among them the Lad in the Lane[203] and The Old Crown, the 15th century Saracen's Head public house and Old Grammar School in Kings Norton[204] and Blakesley Hall.

A number of Georgian buildings survive, including St Philip's Cathedral, Soho House, Perrott's Folly, the Town Hall and much of St Paul's Square. The Victorian era saw extensive building across the city. Major civic buildings such as the Victoria Law Courts (in characteristic red brick and terracotta), the Council House and the Museum & Art Gallery were constructed.[205] St Chad's Cathedral was the first Roman Catholic cathedral to be built in the UK since the Reformation.[206] Across the city, the need to house the industrial workers gave rise to miles of redbrick streets and terraces, many of back-to-back houses, some of which were later to become inner-city slums.[207]

Postwar redevelopment and anti-Victorianism resulted in the loss of dozens of Victorian buildings like Birmingham New Street Station and the old Central Library, often replaced by brutalist architecture.[208] Sir Herbert Manzoni, City Engineer and Surveyor of Birmingham from 1935 until 1963, believed conservation of old buildings was sentimental and that the city did not have any of worth anyway.[209] In inner-city areas too, much Victorian housing was demolished and redeveloped. Existing communities were relocated to tower block estates like Castle Vale.[210]

In a partial reaction against the Manzoni years, Birmingham City Council is demolishing some of the brutalist buildings like the Central Library and has an extensive tower block demolition and renovation programme. There has been much redevelopment in the city centre in recent years, including the award-winning[211] Future Systems' Selfridges building in the Bullring Shopping Centre, the Brindleyplace regeneration project, the Millennium Point science and technology centre, and the refurbishment of the iconic Rotunda building. Funding for many of these projects has come from the European Union; the Town Hall for example received £3 million in funding from the European Regional Development Fund.[212]

Highrise development has slowed since the 1970s and mainly in recent years because of enforcements imposed by the Civil Aviation Authority on the heights of buildings as they could affect aircraft from the Airport (e.g. Beetham Tower).[213]

Transport

Partly because of its central location, Birmingham is a major transport hub on the motorway, rail and canal networks.[214] The city is served by the M5, M6, M40, and M42 motorways, and probably the best known motorway junction in the UK: Spaghetti Junction.[215] The M6 passes through the city on the Bromford Viaduct, which at 3.5 miles (5.6 km) is the longest bridge in the United Kingdom.[216]

Birmingham Airport, located 6 miles (9.7 km) east of the city centre in the neighbouring borough of Solihull, is the seventh busiest by passenger traffic in the United Kingdom and the third busiest outside the London area after Manchester and Edinburgh. It is the largest base for Flybe, Europe's largest regional airline,[217] and a major base for Ryanair, Monarch Airlines and Thomson Airways. Airline services exist to many destinations in Europe, North America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East and Asia.[218]

Birmingham New Street is the busiest railway station in the United Kingdom outside London, both for passenger entries and exits and for passenger interchanges.[219] It is the national hub for CrossCountry, the most extensive long-distance train network in Britain,[220] and a major destination for Virgin Trains services from London Euston, Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Waverley.[221] Birmingham Moor Street and Birmingham Snow Hill form the northern termini for Chiltern Railways express trains running from London Marylebone.[222] Local and regional services are operated from all of Birmingham's stations by London Midland.[223] Curzon Street railway station is planned to be the northern terminus for phase 1 of the High Speed 2 rail link from London, due to open in 2026.[224]

The National Express Group headquarters are located in Digbeth, in offices above Birmingham Coach Station, which forms the national hub of the company's coach network.

.jpg)

Local public transport in Birmingham is co-ordinated by Centro, the Integrated Transport Authority for the West Midlands county. Branded as "Network West Midlands", Centro's network includes the busiest urban rail system in the UK outside London, with 122 million passenger entries and exits per annum;[225] the busiest urban bus system outside London, with 300.2 million passenger journeys per annum;[226] and the Midland Metro, a light rail system which operates between Snow Hill and Wolverhampton via Bilston, Wednesbury and West Bromwich,[227] and which is currently being extended from Snow Hill further into Birmingham city centre.[228] Bus routes are mainly operated by National Express West Midlands, which accounts for over 80% of all bus journeys in Birmingham, though there are around 50 other, smaller registered bus companies.[229] The number 11 outer circle bus routes are the longest urban bus routes in Europe, being 26 miles (42 km) long[230] with 272 bus stops.[231]

An extensive canal system remains from the Industrial Revolution, with the city having more miles of canal than Venice, although because Birmingham is much larger than Venice the canals are less of a prominent feature than they are in Venice.[232] Nowadays the canals are mainly used for leisure purposes, and canalside regeneration schemes such as Brindleyplace have turned the canals into tourist attractions.

Education

Further and higher education

Birmingham is home to five universities: Aston University, University of Birmingham, Birmingham City University, University College Birmingham and Newman University.[233] The city also hosts major campuses of the University of Law and BPP University, as well as the Open University's West Midlands regional base.[234] In 2011 Birmingham had 78,259 full-time students aged 18–74 resident in the city during term time, more than any other city in the United Kingdom outside London.[235] Birmingham has 32,690 research students, also the highest number of any major city outside London.[236]

The Birmingham Business School, established by Sir William Ashley in 1902, is the oldest graduate-level business school in the United Kingdom.[237] Another top business school in the city includes Aston Business School, one of fewer than 1% of business schools globally to be granted triple accreditation,[238] and Birmingham City Business School. The Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham School of Acting and Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, all now part of Birmingham City University, offer higher education in specific arts subjects.

Birmingham is an important centre for religious education. St Mary's College, Oscott is one of the three seminaries of the Catholic Church in England and Wales;[239] Woodbrooke is the only Quaker study centre in Europe;[240] and Queen's College, Edgbaston is an ecumenical theological college serving the Church of England, the Methodist Church and the United Reformed Church.

Birmingham Metropolitan College is one of the largest further education colleges in the country,[241] with fourteen campuses spread across Birmingham and into the Black Country and Worcestershire.[242] South & City College Birmingham has nine campuses spread throughout the city.[243] Bournville College is based in a £66 million, 4.2 acre campus in Longbridge that opened in 2011.[244] Fircroft College is a residential college based in a former Edwardian mansion in Selly Oak, founded in 1909 around a strong commitment to social justice, with many courses aimed at students with few prior formal qualifications.[245] Queen Alexandra College is a specialist college based in Harborne offering further education to visually impaired or disabled students from all over the United Kingdom.[246]

Primary and secondary education

Birmingham City Council is England's largest local education authority, directly or indirectly responsible for 25 nursery schools, 328 primary schools, 77 secondary schools[247] and 29 special schools.[248] and providing around 3,500 adult education courses throughout the year.[249] Most of Birmingham's state schools are community schools run directly by Birmingham City Council in its role as local education authority (LEA). However, there are a large number of voluntary aided schools within the state system. Since the 1970s, most secondary schools in Birmingham have been 11-16/18 comprehensive schools, while post GCSE students have the choice of continuing their education in either a school's sixth form or at a further education college. Birmingham has always operated a primary school system of 4–7 infant and 7–11 junior schools.

King Edward's School, Birmingham, founded in 1552 by King Edward VI, is the one of the oldest and the most prestigious schools in the city, constantly setting high academic standards in GCSE and IB and having many notable alumni pass through its doors, such as J.R.R Tolkien, author of the Lord of the Rings books and the Hobbit. Notable independent schools in the city include the Birmingham Blue Coat School, King Edward VI High School for Girls and Edgbaston High School for Girls. The seven schools of The King Edward VI Foundation are known nationally for setting very high academic standards and all the schools consistently achieve top positions in national league tables.[250]

Public services

In Birmingham libraries, leisure centres, parks, play areas, transport, street cleaning and waste collection face cuts among other services. Albert Bore, leader of Birmingham City Council called on the government to change radically how local services are funded and provided. It is claimed government cuts to local authorities have hit Birmingham disproportionately.[251] Child protection services within Birmingham were rated "inadequate" by OFSTED for four years running between 2009 and 2013, with 20 child deaths since 2007 being investigated.[252] In March 2014 the government announced that independent commissioner would be appointed to oversee improvements to children's services within the city.[253]

Library services

The former Birmingham Central Library, opened in 1972, was considered to be the largest municipal library in Europe.[254] Six of its collections were designated by the Arts Council England as being "pre-eminent collections of national and international importance", out of only eight collections to be so recognised in local authority libraries nationwide.[255] A new Library of Birmingham in Centenary Square, replacing Central Library, was opened on 3 September 2013. It was designed by the Dutch architects Mecanoo and has been described as "a kind of public forum ... a memorial, a shrine, to the book and to literature".[256] This library faces cuts, due to reduced funding from Central government.[257]

There are 41 local libraries in Birmingham, plus a regular mobile library service.[258] The library service has 4 million visitors annually.[259] Due to budget cuts, four of the branch libraries risk closure whilst services may be reduced elsewhere.[257]

Emergency services

Law enforcement in Birmingham is carried out by West Midlands Police, whose headquarters are at Lloyd House in Birmingham City Centre. With 87.92 recorded offences per 1000 population in 2009–10, Birmingham's crime rate is above the average for England and Wales, but lower than any of England's other major core cities and lower than many smaller cities such as Oxford, Cambridge or Brighton.[260] Fire and rescue services in Birmingham are provided by West Midlands Fire Service and emergency medical care by West Midlands Ambulance Service.

Healthcare

There are several major National Health Service hospitals in Birmingham. The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, adjacent to the Birmingham Medical School in Edgbaston, houses the largest critical care unit in Europe,[261] and is also the home of the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine, treating military personnel injured in conflict zones.[262] Other general hospitals in the city include Heartlands Hospital, Good Hope Hospital in Sutton Coldfield and City Hospital in Winson Green. There are also many specialist hospitals, such as Birmingham Children's Hospital, Birmingham Women's Hospital, Birmingham Dental Hospital, and the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital.

Birmingham saw the first ever use of radiography in an operation,[263] and the UK's first ever hole-in-the-heart operation was performed at Birmingham Children's Hospital.[264]

See also Healthcare in West Midlands.

Water supply

The Birmingham Corporation Water Department was set up in 1876 to supply water to Birmingham, up until 1974 when its responsibilities were transferred to Severn Trent Water. Most of Birminghams water is supplied by the Elan aqueduct,[265] opened in 1904; water is fed by gravity to Frankley Reservoir, Frankley, and Bartley Reservoir, Bartley Green, from reservoirs in the Elan Valley, Wales.[266]

Energy from waste

Within Birmingham the Tyseley Energy from Waste Plant, a large incineration plant built in 1996 for Veolia,[267] burns some 366,414 tonnes of household waste annually and produces 166,230 MWh of electricity for the National Grid along with 282,013 tonnes of carbon dioxide.[268] Birmingham Friends of the Earth have strongly opposed the facility for contributing to climate change, causing air pollution and reducing recycling rates in the city.

Another energy-from-waste centre using pyrolysis technology has been granted planning permission at Washwood Heath.[269][270]

Sport

Birmingham has played an important part in the history of sport. The Football League – the world's first league football competition – was founded by Birmingham resident and Aston Villa director William McGregor, who wrote to fellow club directors in 1888 proposing "that ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home-and-away fixtures each season".[271] The modern game of tennis was developed between 1859 and 1865 by Harry Gem and his friend Augurio Perera at Perera's house in Edgbaston,[272] with the Edgbaston Archery and Lawn Tennis Society remaining the oldest tennis club in the world.[273] The Birmingham and District Cricket League is the oldest cricket league in the world,[274] and Birmingham was the host for the first ever Cricket World Cup, a Women's Cricket World Cup in 1973.[275] Birmingham was the first city to be named National City of Sport by the Sports Council.[276] Birmingham was selected ahead of London and Manchester to bid for the 1992 Summer Olympics,[277] but was unsuccessful in the final selection process, which was won by Barcelona.[278]

Today the city is home of two of the country's oldest professional football teams: Aston Villa F.C., which was founded in 1874 and plays at Villa Park; and Birmingham City F.C., which was founded in 1875 and plays at St Andrew's. Rivalry between the clubs is fierce and the fixture between the two is called the Second City derby.[279] Aston Villa currently play in the Premier League and have been League champions on seven occasions and European Champions in 1982. Birmingham City currently play in the Championship, the second tier of English football. Another Premier League club, West Bromwich Albion F.C., play just outside the city centre at The Hawthorns.

Seven times County Championship winners Warwickshire County Cricket Club play at Edgbaston Cricket Ground, which also hosts test cricket and one day internationals and is the largest cricket ground in the United Kingdom after Lord's.[280] Edgbaston was the scene of the highest ever score by a batsman in first-class cricket, when Brian Lara scored 501 not out for Warwickshire in 1994.[281]

Birmingham has a professional Rugby Union club, Moseley R.F.C., who play at Billesley Common; with a second professional club, Birmingham & Solihull R.F.C., playing at Damson Park in the neighbouring borough of Solihull. The city also has a rugby league club, the Birmingham Bulldogs, who compete in the Co-operative RLC Midlands Premier League (RLC). The city is also home to one of the oldest American Football teams in the BAFA National Leagues, the Birmingham Bulls.

Two major championship golf courses lie on the city's outskirts. The Belfry near Sutton Coldfield is the headquarters of the Professional Golfers' Association[282] and has hosted the Ryder Cup more times than any other venue.[283] The Forest of Arden Hotel and Country Club near Birmingham Airport is also a regular host of tournaments on the PGA European Tour, including the British Masters and the English Open.[284]

The AEGON Classic is, alongside Wimbledon and Eastbourne, one of only three UK tennis tournaments on the WTA Tour.[285] It is played annually at the Edgbaston Priory Club, which in 2010 announced plans for a multimillion-pound redevelopment, including a new showcase centre court and a museum celebrating the game's Birmingham origins.[286]

The Alexander Stadium in Perry Barr is the headquarters of UK Athletics,[287] and one of only two British venues to host fixtures in the elite international IAAF Diamond League.[288] It is also the home of Birchfield Harriers, which has many international athletes among its members. The National Indoor Arena hosted the 2007 European Athletics Indoor Championships and 2003 IAAF World Indoor Championships, as well as hosting the annual Aviva Indoor Grand Prix – the only British indoor athletics fixture to qualify as an IAAF Indoor Permit Meeting[289] – and a wide variety of other sporting events. The venue will host the World Indoor Athletics Championships for a second time, when they come to Birmingham in 2018.

Professional boxing, hockey, skateboarding, stock-car racing, greyhound racing and speedway also takes place within the city.

Food and drink

Birmingham's development as a commercial town was originally based around its market for agricultural produce, established by royal charter in 1166. Despite the industrialisation of subsequent centuries this role has been retained and the Birmingham Wholesale Markets remain the largest combined wholesale food markets in the country,[290] selling meat, fish, fruit, vegetables and flowers and supplying fresh produce to restaurateurs and independent retailers from as far as 100 miles (161 km) away.[291]

Birmingham is the only English city outside London to have five Michelin starred restaurants: Simpson's in Edgbaston, Turners in Harborne, Carters of Moseley and Purnell's and Adam's in the city centre.[292]

Birmingham based breweries included Ansells, Davenport's and Mitchells & Butlers.[293] Aston Manor Brewery is currently the only brewery of any significant size. Many fine Victorian pubs and bars can still be found across the city, whilst there is also a plethora of more modern nightclubs and bars, notably along Broad Street.[294]

The Wing Yip food empire first began in the city and now has its headquarters in Nechells.[295] The Balti, a type of curry, was invented in the city, which has received much acclaim for the 'Balti Belt' or 'Balti Triangle'.[296] Famous food brands that originated in Birmingham include Typhoo tea, Bird's Custard, Cadbury's chocolate and HP Sauce.

There is also a thriving independent and artisan food sector in Birmingham, encompassing microbreweries like Two Towers,[297] and collective bakeries such as Loaf.[298] Recent years have seen these businesses increasingly showcased at farmers markets,[299] popular street food events[300] and food festivals including Birmingham Independent Food Fair.[301][302]

Media

Birmingham has several major local newspapers – the daily Birmingham Mail and the weekly Birmingham Post and Sunday Mercury, all owned by the Trinity Mirror. Forward (formerly Birmingham Voice) is a freesheet produced by Birmingham City Council, which is distributed to homes in the city. Birmingham is also the hub for various national ethnic media, and the base for two regional Metro editions (East and West Midlands).

Birmingham has a long cinematic history; The Electric on Station Street is the oldest working cinema in the UK,[303] and Oscar Deutsch opened his first Odeon cinema in Brierley Hill during the 1920s. The largest cinema screen in the West Midlands is located at Millennium Point in the Eastside. Birmingham has also been the location for films including Felicia's Journey of 1999, which used locations in Birmingham that were used in Take Me High of 1973 to contrast the changes in the city.[304]

The BBC has two facilities in the city. The Mailbox, in the city centre, is the national headquarters of BBC English Regions[305] and the headquarters of BBC West Midlands and the BBC Birmingham network production centre. These were previously located at the Pebble Mill Studios in Edgbaston. The BBC Drama Village, based in Selly Oak, is a production facility specialising in television drama.[306]

Central/ATV studios in Birmingham were the location for the recording of many programmes for ITV including Tiswas and Crossroads, until the complex was closed in 1997,[307] and Central moved to its current Gas Street studios. These were also the main hub for CITV, until that was moved to Manchester in 2004. Central's output from Birmingham now consists of only the West and East editions of the regional news programme Central Tonight.

The city is served by numerous national and regional radio stations, as well as local radio stations. These include Free Radio Birmingham & Free Radio 80s, Capital Birmingham, Heart West Midlands, Absolute Radio, and Smooth Radio. The city also has a community radio scene, with stations including Big City Radio, New Style Radio, Switch Radio, Raaj FM, and Unity FM.

The Archers, the world's longest running radio soap, is recorded in Birmingham for BBC Radio 4.[308]

Twin cities

Birmingham has six sister cities;[309]

There are also Treaties of Friendship between Birmingham and Mirpur in Azad Kashmir from where about 90,000 Birmingham citizens originate.[309] Birmingham, Alabama, USA, is named after the city and shares an industrial kinship.

Friendship cities:[309]

Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan[315]

Mirpur, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan[315]

References

Notes

- 1 2 "2011 Census: Key Statistics for Local Authorities in England and Wales". ONS. Retrieved 25 December 2012

- 1 2 3 4 "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ "Population and Census". Birmingham City Council. 7 July 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ "2011 Census: Population and household estimates fact file, unrounded estimates, local authorities in England and Wales (Excel sheet 708Kb)" (xls). Office for National Statistics. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "2011 Census - Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ Istrate, Emilia; Nadeau, Carey Anne (November 2012). "Global MetroMonitor". Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- 1 2 Uglow 2011, pp. iv, 860–861; Jones 2008, pp. 14, 19, 71, 82–83, 231–232

- ↑ Hopkins 1989, p. 26

- ↑ Berg 1991, pp. 174, 184; Jacobs, Jane (1969). The economy of cities. New York: Random House. pp. 86–89. OCLC 5585.

- ↑ Ward 2005, jacket; Briggs, Asa (1990) [1965]. Victorian Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 185; 187–189. ISBN 0-14-013582-0.; Jenkins, Roy (2004). Twelve cities: a personal memoir. London: Pan Macmillan. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-330-49333-7. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Employee jobs (2012)". Nomis – official labour market statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- 1 2 "The World According to GaWC 2010". Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ "Table 0 – All students by institution, mode of study, level of study and domicile 2008/09". Higher education Statistics Agency. Retrieved 31 January 2011.; Aldred, Tom (2009). "University Challenge: Growing the Knowledge Economy in Birmingham" (PDF). London: Centre for Cities. p. 12. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Maddocks, Fiona (6 June 2010). "Andris Nelsons, magician of Birmingham". The Observer (London: Guardian News and Media). Retrieved 31 January 2011.; Craine, Debra (23 February 2010). "Birmingham Royal Ballet comes of age". The Times (Times Newspapers). Retrieved 31 January 2011.; "The Barber Institute of Fine Arts". Johansens. Condé Nast. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ↑ Price, Matt (2008). "A Hitchhiker' s Guide to the Gallery - Where to see art in Birmingham and the West Midlands" (PDF). London: Arts Co. Retrieved 11 November 2013.; King, Alison (13 October 2012). "Forget Madchester, it's all about the B-Town scene". The Independent (London: Independent News and Media). Retrieved 11 November 2013.; Segal, Francesca (3 August 2008). "Why Birmingham rules the literary roost". The Observer (London: Guardian News and Media). Retrieved 11 November 2013.; Alexander, Lobrano (6 January 2012). "Birmingham, England - Could England's second city be first in food?". New York Times (The New York Times Company). Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ↑ "Travel Trends, 2014".

- ↑ "Brummagem". Worldwidewords.com. 13 December 2003. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ↑ William Hutton (1783). An History of Birmingham.

- ↑ Leather 2001, p. 2; Kinvig, R. H. (1970) [1950]. "The Birmingham District in Domesday Times". In Kinvig, R. H.; Smith, J. G.; Wise, M. G. Birmingham and its Regional Setting: A Scientific Survey. New York: S. R. Publishers Limited. p. 113. ISBN 0-85409-607-8.

- ↑ Hodder 2004, p. 23

- ↑ Hodder 2004, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Hodder 2004, pp. 33, 43