Jimmy Frise

| Jimmy Frise | |

|---|---|

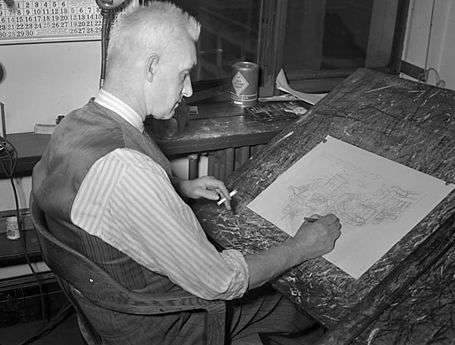

Jimmy Frise at his drawing board | |

| Born |

James Llewellyn Frise 16 October 1891 Scugog Island, Ontario, Canada |

| Died |

13 June 1948 Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

Notable works |

|

| Awards | Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame |

| Signature | |

| |

The Canadian cartoonist James Llewellyn "Jimmy" Frise (/fraɪz/,[1] 16 October 1891 – 13 June 1948) is best known for his work on the comic strip Birdseye Center.

Born in Scugog Island, Ontario, Frise moved at 19 and found illustration work on the Toronto Star's Star Weekly supplement. He left hand was severely injured at Vimy Ridge in 1917 during World War I, but his drawing hand was unhurt, and he continued cartooning at the Star upon his return. In 1919 he began his first weekly comic strip, Life's Little Comedies, which evolved into the rural-centred humorous Birdseye Center in 1923. He moved to the Montreal Standard in 1947, but as the Star kept publication rights to Birdseye Center Frise continued it Juniper Junction with strongly similar characters and situations. Doug Wright took over the strip after Frise's sudden death from a heart attack in 1948, and it went on to become the longest-running strip in English-Canadian comics history.

Life and career

James Llewellyn Frise was born 16 October 1891[2] in Scugog Island, Ontario, the only son of John Frise (d. 1922), who was a farmer, and Hannah née Barker (d. 1933), who had immigrated with her family from England to Port Perry when she was two. He grew up in Seagrave and Myrtle and went to school in Port Perry. There he struggled with spelling—even with his own middle name—and developed an obsession with drawing.[1]

Throughout his teens, friends and teachers encouraged Frise to move to Toronto to pursue a drawing career. In 1910 he moved there, though without aiming to develop his art—rather he sought work and found it as an engraver and printer at the Rolph, Clark, Stone lithography firm; he spent six months drawing maps for the Canadian Pacific Railway company indicating lots for sale in Saskatchewan.[1]

Star Weekly, 12 November 1910

While seeking another job he read in the Toronto Star an exchange between a farmer and an editor in which the editor extolled the virtues of farmlife only to have the farmer rebut him and challenge him to try out farming. Frise drew a cartoon of the editor struggling to milk a cow and a farmer as an editor; he submitted it to the Star, where it appeared in the Star Weekly supplement on that 12 November. He visited the Star's offices the following Monday and the Editor-in-Chief hired him immediately. He began by lettering titles and touching up photos until the Star Weekly's editor J. Herbert Cranston enlisted him for his drawing skills. Frise illustrated news stories and the children's feature The Old Mother Nature Club, and did political cartoons.[1]

Frise took a job at an engraving firm in Montreal in 1916[3] and in the midst of World War I enlisted in the military that 17 May.[1] He had had two years previous experience with the 48th Highlanders of Canada[2] and served at first served in the 69th Battery of the Canadian Field Artillery. He was deployed overseas that September and by November was serving in the 12th Battery at the front, where he employed his farm experience driving horses to move artillery and ammunition. At Vimy Ridge his left hand was severely injured when an enemy shell exploded at an ammunition dump where he was delivering loads of shells. The Star reported its anxiety over the possible loss of "one of Canada’s most promising cartoonists",[1] but his drawing hand—his right—was uninjured. He was discharged after recuperating in Chelmsford, England, and arrived back in Toronto on 1 December 1917 and returned to work, first at the Star and shortly after at the Star Weekly again.[1]

Canadian Field Artillery's 43rd Battery approached Frise in 1919 to illustrate a book on the history of their unit. The volume appeared later in the year under the title Battery Action!, written by Hugh R. Kay, George Magee, and F. A. MacLennan and illustrated with Frise's light-hearted, humorous cartoons rendered in accurate detail.[lower-alpha 1][1]

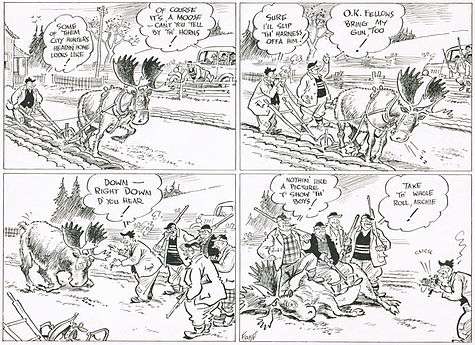

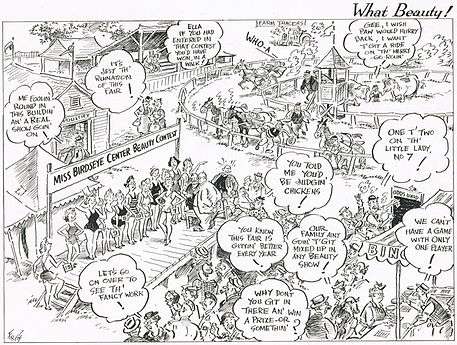

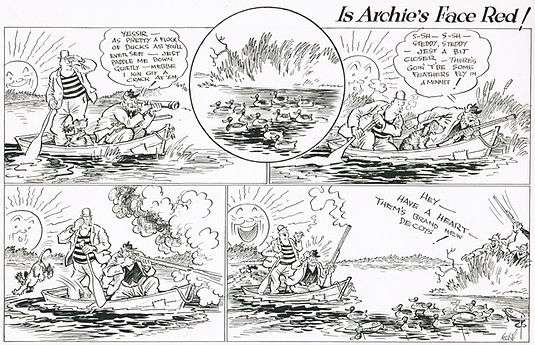

As the Star Weekly's circulation grew, so did its comics section—to 12 pages by 1931. Cranston encouraged Frise to create a Canada-themed comic strip in the vain of W. E. Hill's Among Us Mortals, a Chicago strip which also ran in the Star. Frise protested he could not keep up with a weekly schedule but nonetheless began Life's Little Comedies in 1919. It proved popular and evolved by 1923; it had taken on the influence of John T. McCutcheon's depictions of a fictional rural town in the American Midwest called Bird Center. Frise turned focus to humorous and nostalgic depictions of rural life and renamed his strip Birdseye Center, whose setting he described as "any Canadian village"; its lead characters included bowler-hatted Pigskin Peters, Old Archie and his pet moose Foghorn, and lazy Eli Doolittle and his wife Ruby. The strip grew in popularity and in 1926 was voted favourite comic strip in a readers' poll—as a write-in, since the strip did not appear in the list of options.[4]

- ''Birdseye Center''

-

-

-

From about 1920 Frise shared an office with the journalist and Vimy ridge veteran Greg Clark[1] and began illustrating Clark's tales in the Star of the pair's adventures in Toronto.[4] A selection appeared in a volume titled Which We Did in 1936.[5]

Frise chatted with the frequent visitors to the office. Frise worked at his own pace; he often tore up work-in-progress in dissatisfaction and submitted his strips at the last moment. Frise's tardiness caused such delays in production and distribution that editorial director Harry C. Hindmarsh once demanded Joseph E. Atkinson have something done about it. Atkinson replied, "Harry, The Star Weekly does not go to press without Mr. Frise."[4]

Frise was unconcerned with the resale value of his original artwork and pursued little licensing of his work, amongst which included product endorsements, products such as jigsaw puzzles, and a Birdseye Center Cabin Park on Lake Scugog,[4] opened in 1940.[3] His work provided him well enough that he bought a home in the well-to-do Baby Point neighbourhood.[4]

Frise was wooed away from the Star Weekly by the Montreal Standard in 1947, but the embittered Star maintained all publication rights to Birdseye Center. Unfazed, Frise created the feature Juniper Junction, which featured strongly similar characters and situations. The occasional gag was even borrowed, which Frise argued was his creative property in the first place.

Frise provided the illustrations to Jack Hambleton's cookbook Skillet Skills for Camp and Cottage published in 1947.[6]

During his stay at the Star, Frise struck up a friendship with columnist Greg Clark, then illustrated a series of Clark's articles featuring misadventures of the duo. The friendship lasted until Frise's death in 1948. Clarke eulogized that Frise "gave a whole generation of 30 years smiles and laughter and never hurt a soul in all that time".

After feeling unwell the night before[7] Frise died of a heart attack in his home in Toronto on 13 June 1948.[4]

- Jimmy Frise

-

Frise in 1917 during his service in World War I

-

Frise with friend and collaborator, journalist Greg Clark

-

Frise in 1943

Personal life

Frise stood 5 feet 9 inches (175 cm).[2] He enjoyed the outdoors and pursued fishing and hunting. He often returned to the Lake Scugog area and sometimes spoke about his career there.[3] He was a Methodist Christian.[2]

After returning from his service in World War I, Frise began courting Ruth Elizabeth Gate, who had been born in the US and grew up in Toronto. She worked at an advertising agency, and co-published with her father a magazine in braille and a braille bible. She married Frise on 21 February 1918 and the couple had four daughters, Jean, Ruth, Edythe, and Betty; and a son, John.[1] Frise often featured his spaniel Rusty in his strips.[3]

Legacy

The Montreal cartoonist Doug Wright took the reins of Juniper Junction, which went on to become English Canada's longest-running comic strip.[8] In 1965 the Canadian publisher McClelland & Stewart printed a treasury of Birdseye Center with commentary by Greg Clark and an introduction by Gordon Sinclair.[9]

Scugog Shores Museum in Port Perry holds some samples of Frise's original artwork, and the Province of Ontario erected an Ontario Historical Plaque in front of the museum to commemorate Frise's role in Ontario's heritage.[3] In 2009, Frise was inducted into the Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame.[4]

Notes

References

Works cited

- Bell, John (2006). Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-659-7.

- The Canadian Press (1948-06-14). "Jimmy Frise Dies at Toronto". Ottawa Citizen. p. 16.

- Driver, Elizabeth (2008). "Skillet skills for camp and cottage". Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949. University of Toronto Press. p. 901. ISBN 978-0-8020-4790-8.

- Leroux, Marc (2010). "Gunner James Llewellyn Frise". Canadian Great War Project. Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- Montreal Gazette staff (1936-12-19). "Greg and Jimmy". Montreal Gazette 165 (304). p. 20.

- Ottawa Citizen staff (1965-11-27). "Book notes and comments". Ottawa Citizen. p. 11.

- Plummer, Kevin (2012-06-02). "Historicist: From Lake Scugog to Vimy Ridge: Part one of a two-part look at cartoonist Jimmie Frise's life and work". Torontoist. Archived from the original on 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Plummer, Kevin (2012-06-16). "Historicist: Country Boy and Urbanite: Part two of a two-part look at cartoonist Jimmie Frise's life and work". Torontoist. Archived from the original on 2015-06-12. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Scugog Heritage staff. "Birdseye Center Cabin Park on Lake Scugog". Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

External links

-

Media related to Jimmy Frise at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jimmy Frise at Wikimedia Commons - Scugog Archives of Frise cartoons

- Greg Clarke recalls Jimmy Frise in 1972 CBC Radio interview

- Heer, Jeet (2009-06-06). "Jimmy Frise and the Canadian Cartooning Tradition". Sans Everything. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- Brown, Alan L. "James Llewellyn Frise". Ontario Plaques. Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||