Biological applications of bifurcation theory

Biological applications of bifurcation theory provide a framework for understanding the behavior of biological networks modeled as dynamical systems. In the context of a biological system, bifurcation theory describes how small changes in an input parameter can cause a bifurcation or qualitative change in the behavior of the system. The ability to make dramatic change in system output is often essential to organism function, and bifurcations are therefore ubiquitous in biological networks such as the switches of the cell cycle.

Biological networks and dynamical systems

Biological networks originate from evolution and therefore have less standardized components and potentially more complex interactions than many networks intentionally created by humans such as electrical networks. At the cellular level, components of a network can include a large variety of proteins, many of which differ between organisms. Network interactions occur when one or more proteins affect the function of another through transcription, translation, translocation, or phosphorylation. All these interactions either activate or inhibit the action of the target protein in some way. While humans build networks with some concern for efficiency and simplicity, biological networks are often adapted from others and exhibit redundancy and great complexity. Therefore, it is impossible to predict quantitative behavior of a biological network from knowledge of its organization. Similarly, it is impossible to describe its organization purely from its behavior, though behavior can indicate the presence of certain network motifs.

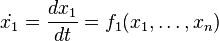

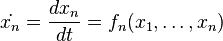

However, with knowledge of network interactions and a set of parameters for the proteins and protein interactions (usually obtained through empirical research), it is often possible to construct a model of the network as a dynamical system. In general, for n proteins, the dynamical system takes the following form[1] where x is typically protein concentration:

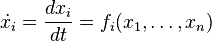

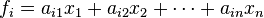

These systems are often very difficult to solve, so modeling of networks as a linear dynamical systems is easier. Linear systems contain no products between xs and are always solvable. They have the following form for all i:

Unfortunately, biological systems are often nonlinear and therefore need nonlinear models.

Input/output motifs

Despite the great potential complexity and diversity of biological networks, all first-order network behavior generalizes to one of four possible I/O motifs: hyperbolic or Michaelis–Menten, ultra-sensitive, bistable, and bistable irreversible (a bistability where negative and therefore biologically impossible input is needed to return from a state of high output).

Ultrasensitive, bistable, and irreversibly bistable networks all show qualitative change in network behavior around certain parameter values – these are their bifurcation points.

Bifurcations

Nonlinear dynamical systems can be most easily understood with a one-dimensional example system where the change in some measurement of protein x's abundance depends only on itself:

Instead of solving the system analytically which can be difficult for many functions, it is often best to take a geometric approach and draw a phase portrait. A phase portrait is a qualitative sketch of the differential equation's behavior that shows equilibrium solutions or fixed points and the vector field on the real line.

Bifurcations describe changes in the stability or existence of fixed points as a control parameter in the system changes. As a very simple explanation of a bifurcation in a dynamical system, consider an object balanced on top of a vertical beam. The mass of the object can be thought of as the control parameter. As the mass of the object increases, the beam's deflection from vertical, which is x, the dynamic variable, remains relatively stable. But when the mass reaches a certain point – the bifurcation point – the beam will suddenly buckle. Changes in the control parameter eventually changed the qualitative behavior of the system.

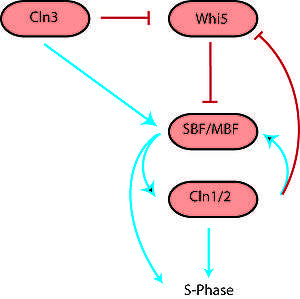

For a more rigorous example, consider the dynamical system shown in figure 2

where ε is the control parameter. At first, when ε is greater than 0, the system has one stable fixed point and one unstable fixed point. As ε decreases the fixed points move together, briefly collide into a semi-stable fixed point at ε = 0, and then cease to exist when ε < 0.

In this case, because the behavior of the system changes significantly when the control parameter ε is 0, 0 is a bifurcation point. This example bifurcation is called the saddle-node bifurcation and its bifurcation diagram (this time for  ) is shown in figure 3.

) is shown in figure 3.

Other types of bifurcations are also important in dynamical systems, but the saddle node bifurcation is more important in biology. The reason for this is that biological systems are real and include small stochastic variations. For example, adding a very small term, 0 < h << 1 to a pitchfork bifurcation yields a stable fixed point and a saddle node bifurcation[1] (figure 4). Similarly, a small error term collapses a transcritical bifurcation to two saddle-node bifurcations.

Combined saddle node bifurcations in a system can generate multistability. Bistability (a special case of multistability) is an important property in many biological systems often produced by network architecture that contains positive feedback interactions and ultra-sensitive elements. Bistable systems are hysteretic, that is, their behavior depends on the history of the input.[2] A hysteretic network can produce different output values for the same input value depending on its state (produce by the history of the input), a property crucial for switch-like control of cellular processes.[2]

Examples

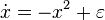

Networks with bifurcation in their dynamics control many important transitions in the cell cycle. The G1/S, G2/M, and Metaphase–Anaphase transitions all act as biochemical switches in the cell cycle.

In population ecology, the dynamics of food web interactions networks can exhibit Hopf bifurcations. For instance, in an aquatic system consisting of a primary producer, a mineral resource, and an herbivore, researchers found that patterns of equilibrium, cycling, and extinction of populations could be qualitatively described with a simple nonlinear model with a Hopf Bifurcation.[3]

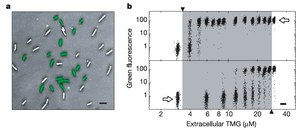

Galactose utilization in budding yeast (S. cerevisiae) is measurable through GFP expression induced by the GAL promoter as a function of changing galactose concentrations. The system exhibits bistable switching between induced and non-induced states.[4]

Similarly, lactose utilization in E. coli as a function of thyo-methylgalactoside (a lactose analogue) concentration measured by a GFP-expressing lac promoter (figure 5) exhibits hysteresis and bistability.[5]

See also

- Biochemical switches in the cell cycle

- Dynamical Systems

- Dynamical systems theory

- Bifurcation Theory

- Cell cycle

- Theoretical Biology

- Computational Biology

- Systems Biology

- Cellular model

References

- 1 2 Strogatz S.H. (1994), Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos, Perseus Books Publishing

- 1 2 David Angeli, James E. Ferrell, Jr., and Eduardo D.Sontag. Detection of multistability, bifurcations, and hysteresis in a large class of biological positive-feedback systems. PNAS February 17, 2004 vol. 101 no. 7 1822-1827

- ↑ Gregor F. Fussmann, Stephen P. Ellner, Kyle W. Shertzer, and Nelson G. Hairston Jr. Crossing the Hopf Bifurcation in a Live Predator–Prey System. Science. 17 November 2000: 290 (5495), 1358–1360. doi:10.1126/science.290.5495.1358

- ↑ Song C, Phenix H, Abedi V, Scott M, Ingalls BP, et al. 2010 Estimating the Stochastic Bifurcation Structure of Cellular Networks. PLoS Comput Biol 6(3): e1000699. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000699

- ↑ Ertugrul M. Ozbudak, Mukund Thattai, Han N. Lim, Boris I. Shraiman & Alexander van Oudenaarden. Multistability in the lactose utilization network of Escherichia coli. Nature. 2004 Feb 19 ;427(6976):737–40