Bindusara

| Bindusara | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chakravartin | |||||

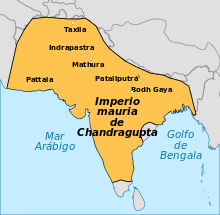

The Maurya Empire after Bindusara's death 269 | |||||

| 2nd Mauryan emperor | |||||

| Reign | c. 297 – c. 273 BCE[1] | ||||

| Coronation | 297 BCE[1] | ||||

| Predecessor | Chandragupta Maurya | ||||

| Successor | Ashoka | ||||

| Born | 320 BCE | ||||

| Died | 273 BCE (aged 48)[1] | ||||

| Spouse |

Susima's mother[2] Subhadrangi | ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Maurya | ||||

| Father | Chandragupta Maurya | ||||

| Mother | Durdhara | ||||

| Religion | Ājīvika[3] | ||||

| Maurya Kings (324 BCE – 180 BCE) | |

| Chandragupta | (324-297 BCE) |

| Bindusara | (297-273 BCE) |

| Ashoka | (268-232 BCE) |

| Dasharatha | (232-224 BCE) |

| Samprati | (224-215 BCE) |

| Shalishuka | (215-202 BCE) |

| Devavarman | (202-195 BCE) |

| Shatadhanvan | (195-187 BCE) |

| Brihadratha | (187-180 BCE) |

| Pushyamitra (Shunga Empire) |

(180-149 BCE) |

Bindusara Maurya (r. c. 320–273 BCE) was the second emperor of the Maurya Empire. During his reign, the empire expanded southwards. He had two well-known sons, Susima and Ashoka, who were the viceroys of Taxila and Ujjain, respectively. The Greeks called him Amitrochates or Allitrochades – the Greek transliteration for the Sanskrit word Amitraghata "Slayer of enemies". He was also called Ajatashatru "Man with no enemies" in Sanskrit[4][5] (not to be confused with Ajatashatru, son of Bimbisara, who ruled Haryanka Magadha from 491–461 BCE).

Life

Bindusara was the son of the first Mauryan Emperor, Chandragupta Maurya, and his Empress-Consort, Durdhara. His birth name was Simhasena.[6] According to a legend mentioned by the Jains, Chandragupta's advisor Chanakya used to feed the emperor small doses of poison to build his immunity against possible poisoning attempts by enemies of the throne.[7] One day, Chandragupta not knowing about the poison, shared his food with his pregnant wife, Durdhara, who was 7 days away from delivery. The empress not immune to the poison collapsed and died within few minutes. Chanakya entered the room the very time she collapsed, and to save the child in the womb, he immediately cut open the dead empress' womb and took the baby out. By that time a drop of poison had already reached the baby and touched its head due to which child got a permanent bluish spot (a "bindu") on his forehead. Thus, the newborn was named "Bindusara".[8]

Bindusara, just 22 years old, inherited a large empire that consisted of what is now the northern, central and eastern parts of India along with parts of Afghanistan and Balochistan. Bindusara extended this empire to South India as far as modern Karnataka. He brought sixteen states under the Mauryan Empire and thus conquered almost all of the Indian peninsula (he is said to have conquered the "land between the two seas" – the peninsular region between the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea). Bindusara didn't conquer the Dravidian kingdoms of the Chola dynasty, ruled by King Ilamcetcenni, the Pandyan dynasty and the Chera dynasty. Kalinga (modern Odisha) was the only kingdom outside of South India that didn't form part of Bindusara's empire. It was later conquered by his son Ashoka, who served as the viceroy of Ujjain during his father's reign.

According to a legend, Chandragupta, though fond of his son, believed that he would never be a great king as he never learned to love anything passionately, whether be it any of his wives or religion or the empire itself.

Bindusara's life has not been documented as well as that of his father Chandragupta or of his son Ashoka. Chanakya continued to serve as prime minister during his reign. According to the medieval Tibetan scholar Taranatha who visited India, Chanakya helped Bindusara "to destroy the nobles and kings of the sixteen kingdoms and thus to become absolute master of the territory between the eastern and western oceans."[9] The Divyavadana gives the story of a revolt in Taxila and the dispatch of the crown-prince Ashoka to quell it. The people of city received him with ovation by declaring that they were not opposed either to prince or to Bindusara but to the wicked officials who practiced oppression over them.[10]

Ambassadors from the Seleucid Empire (such as Deimachus) and Egypt visited his courts. He maintained good relations with the Hellenic World.

.jpg)

Bindusara renounced his throne in favour of his son Ashoka in 272 BCE (some records say 268 BCE) and went to do penance.[11]

Religion

Bindusara's guru Pingalavatsa (alias Janasana) was a Brahmin of Ajivika sect follower of Makkhali Gosala Ājīvika.[12] One of Bindusara's Queens, Subhadrangi, was a Brahmin also of the Ajivika sect from Champa (present Bhagalpur district).[13] Bindusara is accredited with giving several grants to Brahmin monasteries (Brahmana-bhatto).[14]

Empire

Bindusara extended his empire further as far as south Mysore. He conquered sixteen states and extended the empire from sea to sea. The empire included the whole of India except the region of Kalinga (modern Orissa) and the Tamil kingdoms of the south. Kalinga was conquered by Bindusara's son Ashoka.

Early Tamil poets speak of Mauryan chariots thundering across the land, their white pennants brilliant in the sunshine. Bindusara campaigned in the Deccan, extending the Mauryan empire in the peninsula to as far as Mysore. He is said to have conquered 'the land between the two seas', presumably the Arabian sea and the Bay of Bengal. It is also possible he conquered the Tamil Kingdoms as they were also the land between two seas.

Administration during Bindusara's Reign

Bindusara maintained good relations with Seleucus I Nicator and the emperors regularly exchanged ambassadors and presents. He also maintained the friendly relations with the Hellenic West established by his father. Ambassadors from Syria and Egypt lived at Bindusara's court.

Tradition had it that he had a friendly relationship with Antiochus I Soter and asked him to send him some sweet wine, dried figs and a sophist:

| “ | But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, There's really nothing nicer than dried figs), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander from Delphi who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece." Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae XIV.67[15] | ” |

Cultural depictions

- Gerson da Cunha portrayed Bindusara in the 2001 Bollywood film, Aśoka.

- Sameer Dharmadhikari plays the role of Bindusara in the television series, Chakravartin Ashoka Samrat.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Singh 2008, p. 331.

- ↑ Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). "Taxila and Ujjaini". Ashoka. Penguin UK. ISBN 8184758073.

- ↑ Sailendra Nath Sen (1999), Ancient Indian History and Civilization, New Age International, p. 142, ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0

- ↑ Strabo (1903), The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, With Notes 1, Translated by H. C. Hamilton, Esq. And W. Falconer, M.A., London: George Bell & Sons, p. 109, retrieved 8 April 2013

- ↑ Strabo (1903), The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, With Notes, 1, Book II, Chapter 1, Section 9, Translated by H. C. Hamilton, Esq. And W. Falconer, M.A., London: George Bell & Sons, p. 109, retrieved 8 April 2013

- ↑ Hurry, Alain Daniélou ; translated from the French by Kenneth (2003). A brief history of India. Rochester. VT: Inner Traditions. p. 108. ISBN 978-0892819232.

- ↑ Wilhelm Geiger (1908). The Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa and their historical development in Ceylon. H. C. Cottle, Government Printer, Ceylon. p. 40. OCLC 559688590.

- ↑ M. Srinivasachariar. History of classical Sanskrit literature (3 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. p. 550. ISBN 978-81-208-0284-1.

- ↑ P.109 A brief history of India by Alain Daniélou, Kenneth Hurry

- ↑ Sen 1999, p. 142.

- ↑ Rice 1889, p. 9.

- ↑ Arthur Llewellyn Basham (1951). History and doctrines of the Ājīvikas: a vanished Indian religion. foreword by L. D. Barnett (1 ed.). London: Luzac. pp. 138, 146. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Anukul Chandra Banerjee (1999). Sanghasen Singh, ed. Buddhism in comparative light. Delhi: Indo-Pub. House. p. 24. ISBN 8186823042. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Beni Madhab Barua; Ishwar Nath Topa (1968). Asoka and his inscriptions 1 (3rd ed.). Calcutta: New Age Publishers. p. 171. OCLC 610327889. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Athenaeus (of Naucratis) (1854). The Deipnosophists,.. or, Banquet of the learned of Athenaeus III. Literally Translated by C. D. Yonge, B. A. London: Henry G. Bohn. p. 1044. Original Classification Number: 888 A96d tY55 1854. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

References

- Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009), "Taxila and Ujjaini", Ashoka, Penguin UK, ISBN 9788184758078

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century, New Delhi: Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999), Ancient Indian History and Civilization (Second ed.), New Age International Publishers, ISBN 81-224-1198-3

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1962), Aśoka (3rd ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas

- Rice, B. Lewis (1889), Inscriptions at Sravana Belgola : a chief seat of the Jains, Bangalore: Mysore Govt. Central Press

| Preceded by Chandragupta Maurya |

Mauryan Emperor 298–272 BC |

Succeeded by Ashoka |