Bhāskara I

Bhāskara (c. 600 – c. 680) (Bengali: ভাস্কর; Marathi: भास्कर commonly called Bhaskara I to avoid confusion with the 12th century mathematician Bhāskara II) was a 7th-century mathematician, who was apparently the first to write numbers in the Hindu decimal system with a circle for the zero, and who gave a unique and remarkable rational approximation of the sine function in his commentary on Aryabhatta's work.[1] This commentary, Āryabhaṭīyabhāṣya, written in 629 CE, is the oldest known prose work in Sanskrit on mathematics and astronomy. He also wrote two astronomical works in the line of Aryabhata's school, the Mahābhāskarīya and the Laghubhāskarīya.[2]

Biography

Little is known about Bhāskara's life. He was "probably a Marathi astronomer".[3] He was born at Bori, in Parbhani district of Maharashtra state in India in 7th century.

His astronomical education was given by his father. Bhaskara is considered the most important scholar of Aryabhata's astronomical school. He and Brahmagupta are two of the most renowned Indian mathematicians who made considerable contributions to the study of fractions.

Representation of numbers

Bhaskara's probably most important mathematical contribution concerns the representation of numbers in a positional system. The first positional representations were known to Indian astronomers about 500 years ago. However, the numbers were not written in figures, but in words or allegories, and were organized in verses. For instance, the number 1 was given as moon, since it exists only once; the number 2 was represented by wings, twins, or eyes, since they always occur in pairs; the number 5 was given by the (5) senses. Similar to our current decimal system, these words were aligned such that each number assigns the factor of the power of ten corresponding to its position, only in reverse order: the higher powers were right from the lower ones.

His system is truly positional, since the same words representing, can also be used to represent the values 40 or 400.[4] Quite remarkably, he often explains a number given in this system, using the formula ankair api ("in figures this reads"), by repeating it written with the first nine Brahmi numerals, using a small circle for the zero . Contrary to his word number system, however, the figures are written in descending valuedness from left to right, exactly as we do it today. Therefore, at least since 629 the decimal system is definitely known to the Indian scientists. Presumably, Bhaskara did not invent it, but he was the first having no compunctions to use the Brahmi numerals in a scientific contribution in Sanskrit.

Further contributions

Bhaskara wrote three astronomical contributions. In 629 he annotated the Aryabhatiya, written in verses, about mathematical astronomy. The comments referred exactly to the 33 verses dealing with mathematics. There he considered variable equations and trigonometric formulae.

His work Mahabhaskariya divides into eight chapters about mathematical astronomy. In chapter 7, he gives a remarkable approximation formula for sin x, that is

which he assigns to Aryabhata. It reveals a relative error of less than 1.9% (the greatest deviation  at

at  ). Moreover, relations between sine and cosine, as well as between the sine of an angle >90° >180° or >270° to the sine of an angle <90° are given.

Parts of Mahabhaskariya were later translated into Arabic.

). Moreover, relations between sine and cosine, as well as between the sine of an angle >90° >180° or >270° to the sine of an angle <90° are given.

Parts of Mahabhaskariya were later translated into Arabic.

Bhaskara already dealt with the assertion that if p is a prime number, then 1 + (p–1)! is divisible by p. It was proved later by Al-Haitham, also mentioned by Fibonacci, and is now known as Wilson's theorem.

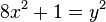

Moreover, Bhaskara stated theorems about the solutions of today so called Pell equations. For instance, he posed the problem: "Tell me, O mathematician, what is that square which multiplied by 8 becomes - together with unity - a square?" In modern notation, he asked for the solutions of the Pell equation  . It has the simple solution x = 1, y = 3, or shortly (x,y) = (1,3), from which further solutions can be constructed, e.g., (x,y) = (6,17).

. It has the simple solution x = 1, y = 3, or shortly (x,y) = (1,3), from which further solutions can be constructed, e.g., (x,y) = (6,17).

See also

References

- ↑ Bhaskara I, Britannica.com

- ↑ Keller (2006, p. xiii)

- ↑ Keller (2006, p. xiii) cites [K S Shukla 1976; p. xxv-xxx], and Pingree, Census of the Exact Sciences in Sanskrit, volume 4, p. 297.

- ↑ B. van der Waerden: Erwachende Wissenschaft. Ägyptische, babylonische und griechische Mathematik. Birkäuser-Verlag Basel Stuttgart 1966 p. 90

Sources

(From Keller (2006))

- M. C. Apaṭe. The Laghubhāskarīya, with the commentary of Parameśvara. Anandāśrama, Sanskrit series no. 128, Poona, 1946.

- v.harish Mahābhāskarīya of Bhāskarācārya with the Bhāṣya of Govindasvāmin and Supercommentary Siddhāntadīpikā of Parameśvara. Madras Govt. Oriental series, no. cxxx, 1957.

- K. S. Shukla. Mahābhāskarīya, Edited and Translated into English, with Explanatory and Critical Notes, and Comments, etc. Department of mathematics, Lucknow University, 1960.

- K. S. Shukla. Laghubhāskarīya, Edited and Translated into English, with Explanatory and Critical Notes, and Comments, etc., Department of mathematics and astronomy, Lucknow University, 2012.

- K. S. Shukla. Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa, with the commentary of Bhāskara I and Someśvara. Indian National Science Academy (INSA), New- Delhi, 1999.

Further reading

- H.-W. Alten, A. Djafari Naini, M. Folkerts, H. Schlosser, K.-H. Schlote, H. Wußing: 4000 Jahre Algebra. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2003 [ISBN 3-540-43554-9], §3.2.1

- S. Gottwald, H.-J. Ilgauds, K.-H. Schlote (Hrsg.): Lexikon bedeutender Mathematiker. Verlag Harri Thun, Frankfurt a. M. 1990 [ISBN 3-8171-1164-9]

- G. Ifrah: The Universal History of Numbers. John Wiley & Sons, New York 2000 [ISBN 0-471-39340-1]

- Keller, Agathe (2006), Expounding the Mathematical Seed. Vol. 1: The Translation: A Translation of Bhaskara I on the Mathematical Chapter of the Aryabhatiya, Basel, Boston, and Berlin: Birkhäuser Verlag, 172 pages, ISBN 3-7643-7291-5.

- Keller, Agathe (2006), Expounding the Mathematical Seed. Vol. 2: The Supplements: A Translation of Bhaskara I on the Mathematical Chapter of the Aryabhatiya, Basel, Boston, and Berlin: Birkhäuser Verlag, 206 pages, ISBN 3-7643-7292-3.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Bhāskara I", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|