Duck and Cover (film)

| Duck and Cover | |

|---|---|

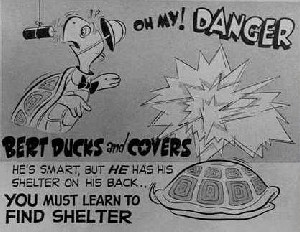

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Anthony Rizzo |

| Written by | Raymond J. Mauer |

| Narrated by | Robert Middleton |

| Distributed by | Archer Productions |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 9 min 15 sec |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Duck and Cover is a civil defense social guidance film that is often popularly mischaracterized as propaganda.[1][2] Film production started in 1951 and it gained its first public screening in January 1952 during the era after the Soviet Union began nuclear testing in 1949 and the Korean War (1950–53) was in full swing.

Funded by the US Federal Civil Defense Administration, it was written by Raymond J. Mauer, directed by Anthony Rizzo of Archer Productions, narrated by actor Robert Middleton and made with the help of schoolchildren from New York City and Astoria, New York.

It was shown in schools as the cornerstone of the government's "duck and cover" public awareness campaign, being aired to generations of United States school children from the early 1950s until 1991, which marked the end of the Cold War.

The US government contracted with Archer to produce Duck and Cover. The film is now in the public domain, and as such is widely available through Internet sources such as YouTube,[3] as well as on DVD.

Plot summary

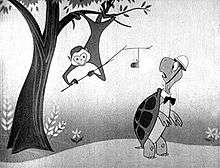

The film starts with an animated sequence, showing an anthropomorphic turtle walking down a road, while picking up a flower and smelling it. A chorus sings the Duck and Cover theme:

There was a turtle by the name of Bert

and Bert the turtle was very alert;

[bang, gasp] Duck, and cover!'

when danger threatened him he never got hurt

he knew just what to do...

He'd duck! [gasp]

And cover!

Duck! [gasp]

And cover! (male) He did what we all must learn to do

(male) You (female) And you (male) And you (deeper male) And you!'

While this goes on, Bert is attacked by a monkey holding a string from which hangs a lit stick of dynamite. Bert ducks into his shell in the nick of time, as the dynamite goes off and blows up both the monkey and the tree in which he is sitting. Bert, however, is shown perfectly safe, because he has ducked and covered.

The film, which is about 10 minutes long, then switches to live footage, as narrator Middleton explains what children should do "when you see the flash" of an atomic bomb. The movie goes on to suggest that by ducking down low in the event of a nuclear explosion, the children would be safer than they would be standing, and explains some basic survival tactics for nuclear war.

The last scene of the film returns to animation in which Bert the Turtle (voiced by Carl Ritchie) summarily asks what everybody should do in the event of an atomic bomb flash and is given the correct answer by a group of unseen children.

Purpose

After nuclear weapons were developed (the first having been developed during the Manhattan Project during World War II), it was realized what kind of danger they posed. The United States held a nuclear monopoly from the end of World War II until 1949, when the Soviets detonated their first nuclear device.

This signaled the beginning of the nuclear stage of the Cold War, and as a result, strategies for survival were thought out. Fallout shelters, both private and public, were built, but the government still viewed it as necessary to explain to citizens both the danger of the atomic (and later, hydrogen) bombs, and to give them some sort of training so that they would be prepared to act in the event of a nuclear strike.

The solution was the duck and cover campaign, of which Duck and Cover was an integral part. Shelters were built, drills were held in towns and schools, and the film was shown to schoolchildren. According to the United States Library of Congress (which declared the film "historically significant" and inducted it for preservation into the National Film Registry in 2004), it "was seen by millions of schoolchildren in the 1950s."

Other media

The song Bert the Turtle (Duck and Cover), performed by Dick Baker, was released as a commercial recording by Coral Records and accompanied by a color campaign pamphlet. It sold 3 million copies.[4]

Accuracy and usefulness

Historians and the public have generally sought to dismiss civil defense advice as mere propaganda. This is despite detailed scientific research programs laying behind the much-mocked UK government civil defense pamphlets of the 1950s and 1960s, including the advice to promptly duck and cover.[7] The advice to duck and cover has made a resurgence in recent years with new scientific evidence to support it.[8]

While this (or any) tactic would be useless for someone at ground zero during a surface burst nuclear explosion, it would be beneficial to the vast majority of people who are positioned away from the blast hypocenter: both the thermal pulse of some weapons and the shrapnel from all weapons (particularly from shattered windows)[9] could be evaded, at least in part. In particular, higher yield thermonuclear weapons have thermal pulses which last for several seconds.[10] By promptly putting something between yourself and the fireball during these crucial couple of seconds, you could avoid or reduce the severity of the burns you would have otherwise received. For those not at ground zero, like a shortened version of the delay between lightning and thunder, there would be a delay between the flash (indicating the need to duck and cover) and the arrival of the blast wave, which will shatter windows turning non-safety glass into missile-like shards, and cause other blast or impact injuries.

To highlight the effect that being indoors can make, despite the lethal radiation & blast zone extending well past her position at Hiroshima,[11] Akiko Takakura survived the effects of a 16 kt atomic bomb at a distance of 300 meters from the hypocenter, with only minor injuries, due in most part to her position in the lobby of the bank of Japan, a reinforced concrete building, at the time of the nuclear explosion.[12][13] In contrast, the unknown person sitting outside, fully exposed, on the steps of the Sumitomo bank, next door to the bank of Japan, received third-degree burns and was then likely killed by the blast, in that order, within 2 seconds.[14]

The advice to cover one's head with anything available, like the picnic blanket and newspaper used by the family in the film, may seem absurd at first when one considers the capabilities of a nuclear weapon, but even a thin barrier such as cloth can reduce the severity of burns on the skin from the thermal radiation – which is light rays in the ultraviolet, visible, and infrared range, and it is this combination of light rays that delivers the burning energy to exposed skin areas;[15] this burning thermal energy would be experienced by people within range for several seconds after the explosion.[16] A photograph taken about 1.3 km from the epicenter of the Hiroshima bomb explosion showed that even leaves from a nearby shrub protected a wooden telephone pole from charring discoloration due to thermal radiation, while the rest of the telephone pole not under the protection of the leaves was charred almost completely black.[17]

Depending on the yield and distance from the explosion the burst of ionizing radiation from the fireball would arrive at an observer's position at the same time as the light flash, leaving the observer little to no time to find cover from this aspect of a nuclear detonation, but subsequently some of this radiation is absorbed and re-emitted by heated fireball air molecules at lower wavelengths, so harmful ionizing radiation may continue for up to a minute during which time ducking and covering would go some way in limiting one's exposure.[15]

One of the most common criticisms of duck and cover encountered is the opinion that prompt ionizing radiation effects would still kill those who duck and cover, regardless of any preventive measures taken. However this is generally incorrect when any nuclear weapon more powerful than 10–30 kilotons is detonated, and even in that case, if the person is indoors the absorbed radiation dose is again not life-threatening.[13] For example, despite the film not being made in the era of megaton-range weapons, for exposed individuals taking no preventive countermeasures the range of harmful ionising radiation effects stays within a circle of radius 2–3 km from ground zero during airbursts of 1 megaton in yield, yet the blast range that would be expected to be lethal to 50% of people is 7.5 km, and the range of thermal effects lethal to 50% of people stretching out to 11 km from ground zero.[18] Naturally, within this 3 km range from a 1-megaton airburst, the fatality rate would be near total for those caught in the open from the extreme blast pressure alone, before any potential radiation sickness could begin.[19]

However, for one caught in the open outside this ~3-kilometer radius from ground zero from a 1-megaton weapon, ducking and covering would drastically increase one's chance of survival, as at this range the radiation hazard is near zero, whereas that from the blast is a chance of 50% fatality at a ~7.5 km range and that of thermal effects 11 km.[18]

If someone was caught in the open, and by surprise, by the same 1-megaton weapon detonation, but ducked and covered in 2 seconds time from first noticing the moment of flash, then that person would have prevented themselves from being exposed to the full brunt of the 1-megaton explosion's thermal energy; instead, approximately 55% of the explosion's total thermal flash energy would have been absorbed over these 2 seconds.[20] In this example, as there is now a 45% reduction in the amount of heat experienced by one ducking and covering, the median lethal thermal range from this 1-megaton weapon can now be more accurately described as equivalent to absorbing the entire flash energy from a 0.55 Mt or 550 kt weapon, if one ducks and covers in 2 seconds.

Henceforth, one's chance of survival at 11 km goes from the previous 50% chance of death if they just stood there, gazing at the 1-megaton fireball as it emits all its energy over tens of seconds, to now a mere sunburn, or a 1st-degree burn injury on exposed skin. With the 50% lethal thermal range being thus downrated to being equivalent to a 550 kt explosion, the 50% lethal thermal radius goes from the previous 11 km without ducking and covering to ~7 km with prompt duck and covering within 2 seconds.[18] One can think of this as going from a scenario were before the majority of people caught in the open, who just stood there staring at the fireball out to a radius of 11 km would probably die from lethal 3rd-degree burns on their unclothed skin, to a scenario now were instead the vast majority of people who 'duck and cover' from 7 km out to 11 km would remain alive, with generally non life-threatening 1st-degree burns & 2nd-degree burns over their exposed skin, with the burn severity naturally depending on their range from the explosion.

Finally, it must be noted that all the lethal ranges given in the referenced graphs, and when discussing the range of Effects of nuclear explosions in general, one must keep in mind what is presented is the most pessimistic of weapon effects ranges. As the scaling laws these tables and graphs were derived from assume a simplistic flat terrain with no intervening skyscrapers or other objects that would attenuate the blast and provide shadowing from the thermal effects. When real world city terrain topography is included in these weapon effects calculations the lethal ranges are downgraded considerably.[21]

According to the 1946 book Hiroshima, in the days between the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs in Japan, one Hiroshima policeman went to Nagasaki to teach police about ducking after the atomic flash. As a result of this timely warning, not a single Nagasaki policeman died in the initial blast. This allowed more surviving Nagasaki police to organize relief efforts than in Hiroshima. Unfortunately, the general population was not warned of the heat/blast danger following an atomic flash because of the bomb’s unknown nature. Many people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki died while searching the skies for the source of the brilliant flash.

Recent scientific analysis has largely supported the general idea of sheltering indoors in response to a nuclear explosion.[8][22] Staying indoors can offer protection both from the initial blast as well as the following radioactive fallout that accumulates during the aftermath. Additionally, such a response would leave roads clear for emergency vehicles to access the area. This is termed the Shelter in place protocol, and together with emergency evacuation advice, they are the two countermeasures to take when the direct effects of nuclear explosions are no longer life-threatening and the need for protective shielding from coming in contact with nuclear weapon debris/fallout in the aftermath of the explosion, begins to become a concern.

There is controversy from some people regarding the actual usefulness of the film. Although it does have counterparts in other countries, such as the British Protect and Survive. Despite this, it is regarded by Amy Lutrell as possibly being an American red scare political tool, to make children frightened of the Soviet Union and communism.[23]

Historical context

The United States' monopoly on nuclear weapons was broken by the Soviet Union in 1949 when it tested its first nuclear explosive (Joe-1), and with this many in the US government and public perceived that the nation was more vulnerable than it had ever been before. Duck-and-cover exercises quickly became a part of Civil Defense drills that every American citizen, from children to the elderly, practiced to be ready in the event of nuclear war. In 1950, during the first big Civil Defense push of the Cold War and coinciding with the Alert America! initiative to educate Americans on nuclear preparedness;[24] The adult-orientated Survival Under Atomic Attack was published and contains "duck and Cover" or more accurately, cover-and-then-duck advice without using those specific terms in its Six Survival Secrets For Atomic Attacks section. 1. Try To Get Shielded 2.Drop Flat On Ground Or Floor 3. Bury Your Face In Your Arms("crook of your elbow").[25] The child-orientated Duck and Cover (film) was produced a year later by the Federal Civil Defense Administration in 1951.

Education efforts on the effects of nuclear weapons proceeded with stops-and-starts in the US due to competing alternatives. In a once classified, 1950s era, US war game that looked at varying levels of war escalation, warning and pre-emptive attacks in the late 1950s early 1960s, it was estimated that approximately 27 million US citizens would have been saved with civil defense education.[26] At the time however the cost of a full scale civil defense program was regarded as lesser in effectiveness, in cost-benefit analysis than a ballistic missile defense(Nike Zeus) system, and as the Soviet adversary was believed to be rapidly increasing their nuclear stockpile, the efficacy of both would begin to enter a diminishing returns trend.[26] When more became known about the cost and limitations of the Nike Zeus system, in the early 1960s the head of the department of defense determined once again that fallout shelters would save more Americans for far less money.[27]

The production of the Duck and Cover film in 1951 by the Federal Civil Defense Administration occurred during the height of the Korean War (1950-1953), and coincided with the first Desert Rock exercises in the Nevada desert which were designed to familiarize the US military with fighting alongside battlefield nuclear weapons, as it was feared that a resolution to the Korean War might need the theatre of operations to first expand across the border into the Peoples Republic of China and require nuclear weapons to end it.

The film was also produced at least one year before the first "hydrogen bomb" or megaton range explosive device was demonstrated to be possible, with test shot Ivy Mike in 1952. At least four years before the first true "hydrogen bomb" of the Soviet Union (USSR), the RDS-37, on November 22, 1955, which yielded 1.6 megatons. About 6 years before the first successful test launch of the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the Soviet Union's R-7 in 1957, up until this time strategic bombers were not but one of the three strategic nuclear triad delivery systems of the modern era but the sole intercontinental nuclear weapon delivery system capable of reaching the USA from the Soviet Union and vice versa.

Before advances in precision guided munitions and physics package miniaturization, "city busting"[28] or countervalue targeting, was a more likely nuclear war scenario, as effective counterforce warfare with nuclear weapons had yet to become all that conceivable, with the potential exceptions of being used in roles where a low degree of accuracy would not result in a waste of a bomb, such as destroying large "rear area" military bases,[29] aircraft carriers, Communist human wave attacks, massive mine fields in trench warfare (which was what the Korean War escalated into), radiological area denial and used at night prior to a frontal assault in the hopes of inducing widespread enemy troop flash blindness. Practically all other counterforce uses of this eras nuclear weapons would be ineffective due to force dispersal, weather factors, poor munition accuracy and the unwieldy physics packages of the nuclear weapons of the era, making them generally unfit for the mobile battlefield.[30][31][32] Therefore, making it likely that combatants who have escalated to the point of contemplating nuclear exchanges, would use their nuclear weapons on immobile and valuable targets, such as the war supporting infrastructure of cities.

It is now estimated that it was not until after 1957 that the USSR attained more than about 50 nuclear munitions in its nuclear weapons arsenal.[33][34] Almost all of this stockpile was likely designed to be air dropped by the Myasishchev M-4[35] and Tupolev Tu-4 bombers as strategic nuclear weapons on US and West European NATO cities respectively. As large numbers of small true tactical nuclear weapons only began to seriously populate the USSR's stockpile in the 1970s and beyond.

Appearance in other media

The 1999 feature film, The Iron Giant, set in 1957, features a social guidance film-within-a-film titled, Atomic Holocaust,[36] the style and tone of which parody the 1952 Duck and Cover film.[37] In another instance, near the end of the feature film, the villainous character suggests they duck and cover into a fallout shelter in response to an offshore nuclear SLBM Polaris missile being launched at their position by the USS Nautilus (SSN-571),[note 1] however all the other male adults in the vicinity claim that this would be of "no use", convincing bystanders and the young protagonist at the heart of the feature film to not attempt to evacuate to shelter.

The Atomic Cafe is a satire documentary film which includes footage from the Duck and Cover film.

The Cartoon Network "Groovies" Atom Ant short had audio clips from this film.

The film is parodied in the 1997 South Park episode "Volcano".

A sample of the lyrics, specifically, "Duck...and cover!", is featured in the opening seconds of the 2006 song "Uncommon Valor: A Vietnam Story" by the rap duo Jedi Mind Tricks.

The 2015 film "Bridge of Spies" features a scene where school children watch the short film.

See also

- Duck and cover, for further discussion of this method of self-defense.

- List of films about nuclear issues

- List of films in the public domain

- Civil Defence Information Bulletin, a 1964 British film which deals with the same topic.

- Protect and Survive, a 1970-80s British information film on the same topic.

- ↑ Despite the fact that the USS Nautilus never had a complement of nuclear missiles and the first test launch of the Polaris occurred on the USS George Washington in 1960, three years after the date in which the movie is set.

References

- ↑ "Architects of Armageddon: the Home Office Scientific Advisers' Branch and civil defence in Britain, 1945–68". Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ↑ The Unexpected Return of 'Duck and Cover'.

- ↑ Duck And Cover (1951) on YouTube

- ↑ Daniel Eagan (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 452. ISBN 0826429777.

- 1 2 Walker, John (June 2005). "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer". Fourmilab. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ "Mock up". Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ↑ Architects of Armageddon: the Home Office Scientific Advisers' Branch and civil defence in Britain, 1945–68

- 1 2 http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/01/the-unexpected-return-of-duck-and-cover/68776/ The Unexpected Return of 'Duck and Cover'

- ↑ The good news about nuclear destruction.

- ↑ General Characteristics of Thermal Radiation from Chapter VII pg 314 of The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan (1977)

- ↑ http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/nuclear/nukgr1.gif

- ↑ Hiroshima Witness interview

- 1 2 "Testimony of Akiko Takakura | The Voice of Hibakusha | The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki | Historical Documents". atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- ↑ "Look at the Exhibits/Damage by the Heat Rays". Pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- 1 2 General Characteristics of Thermal Radiation from Chapter VII of The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan (1977)

- ↑ Field Manual No.1-111: Aviation Brigades (1997), Appendix C, p. 4.

- ↑ Shadow Imprinted on an Electric Pole at the Foot of Meiji Bridge from Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum – Virtual Museum

- 1 2 3 http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/nuclear/nukgr3.gif

- ↑ page 3. see negligible. Meaning that if you are close enough to get a harmful dose of radiation from a 1-megaton weapon, you are going to die from blast effects alone.

- ↑ General Characteristics of Thermal Radiation from Chapter VII pg 314 graph on page. of The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan (1977)

- ↑ Modelling the effects of Nuclear weapons in an urban setting 2011

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/16/science/16terror.html?_r=1

- ↑ Duck and Cover: A Propaganda Film for Red Scare Youngsters?

- ↑ "ALERT AMERICA!".

- ↑ Survival under Atomic Attack; Department of Civil Defense; 1951; archive.org

- 1 2 Net Evaluation Subcommittee. page 27

- ↑ Yanarella 2010, p. 87.

- ↑ "Strategic Bombing, the Nuclear Revolution, and City Busting" (PDF).

- ↑ "Big Picture: Individual Protection Against Atomic Attack - National Archives and Records Administration - ARC Identifier 2569661 / Local Identifier 111-TV-393 - DVD Copied by Katie Filbert - Department of Defense. Circa 5:20 minutes in".

- ↑ Holloway, David (1993). "Soviet Scientists Speak Out". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (Educational foundation for Nuclear Science) 49 (4): 18–19. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ↑ Carey Sublette (3 July 2007). "The Design of Gadget, Fat Man, and "Joe 1" (RDS-1)". Nuclear Weapons FAQ. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ Hansen 1995, pp. 147–149.

- ↑ "Global Nuclear Stockpile, image". Archived from the original on 2014-04-05.

- ↑ "NRDC, Table of Global Nuclear Weapons Stockpiles, 1945-2002 (Natural Resources Defense Council, 2002)".

- ↑ "M-4: The Soviet intercontinental, nuclear-capable aircraft January 27, 2014 Rina Bykova, specially for RIR".

- ↑ "Atomic Holocaust".

- ↑ "'The Iron Giant' Deleted Scenes, 'Duck and Cover' (1951), Jonathan Kim, ReThink Reviews".

- Duck and Cover. Prod. Archer Productions, Inc. Dist. United States Federal Civil Defense Administration. 1951.

- "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". United States Library of Congress, 28 December 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Duck and Cover. |

- Duck and Cover on YouTube

- Production History of Duck and Cover

- Duck and Cover at the Internet Movie Database

- Duck and Cover is available for free download at the Internet Archive (section Prelinger Archives)

- Duck and Cover on Cinemaniacal, in flash, iPod, and TV formats.

- A critical assessment of ducking and covering(waybackmachine)