Bert Leston Taylor

Bert Leston Taylor (November 13, 1866 – March 19, 1921) was an American columnist, humorist, poet, and author.[1]

Bert Leston Taylor became a journalist at seventeen, a librettist at twenty-one, and a successfully published author at thirty-five. At the height of his literary career, he was a central literary figure of the early 20th century Chicago renaissance as well as one of the most celebrated columnists in the United States.

The early years

Bert Leston Taylor was born in Goshen, Massachusetts, on November 13, 1866. He was born in Goshen while his mother was visiting with relatives, but his family were from nearby Williamsburg. His mother was Katherine White (of Dublin, Ireland) and his father was Albert O. Taylor, who worked primarily in the whaling industry. Albert Taylor served in the navy during the Civil War and distinguished himself as a high-ranking officer. While in the navy, he met James Gordon Bennett, and went to work for him at the end of the war to serve as navigator for Bennett’s racing yacht, the Dauntless.

Taylor moved to New York shortly after his birth and grew up in the Manhattan neighborhoods of Greenwich Village and Yorkville. Taylor attended public schools in New York City and excelled at writing evidenced by winning a prize for an original story. From 1881-82, he attended the College of the City of New York (the former name of New York University’s undergraduate college). His original ambition was to become a lawyer, but after two years of studying law, he began to lose interest. He was attracted to music but felt as though he lacked sufficient talent to become a great artist. After he graduated from CCNY, Taylor pursued instead his passion for writing and chose the field of journalism. In 1883, he published his own magazine, The Aerolite, which did not have much success. Harrison Grey Fiske, an established New York journalist, playwright, and theatrical manager, wrote a serial for the paper. In 1887, he moved to Montpelier, Vermont, and worked for The Argus, The Patriot, and later, The Watchman. His column, the “Montpellier Mere Mention,” was the prototype for his famous “A Line o’ Type or Two” column at the Chicago Tribune. Taylor was known for his unique offhand writing style and independent spirit that often compromised his job at those early papers. He later moved south to Barre to start his own paper. The Barre Daily News ran only for a few months, and frustrated from the lack of support from the citizens and local businessmen, he printed the final issue in red ink as a reprisal before leaving town.

From Barre, Taylor moved on to Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1893, and wrote editorials for the Manchester Union. It was in Manchester that Taylor met Walter Lewis who would eventually become a close friend and collaborator. Walter Lewis was a graduate from the New England Conservatory of Music. Together, Taylor as librettist and Lewis as composer, they staged three comic operas.

On November 16, 1895, Taylor married Emma Bonner of Providence, Rhode Island. The following year, they moved west to Duluth, Minnesota after Taylor accepted an editor position at the News-Tribune. Taylor drolly referred to own editorials as the “What-does-the-New-York-Sun-mean-by-the-following?” variety. He remained in Duluth for three years before coming to Chicago in 1899 to work at the Chicago Journal. His journalistic fame began when he took over a column titled, “A Little About Everything”, which originally contained only brief news items. Taylor made the column more popular by adding humor and light verse.

Chicago Tribune (1901–1921)

Editors at the Chicago Tribune noted his originality and growing popularity at the Journal and so made him a generous offer. Taylor accepted and created and conducted his own column at the Tribune called, “A Line o’ Type or Two.” He worked on the top floor of the new Tribune building, which was a seventeen-story skyscraper built in 1902 on the corner of Madison and Dearborn streets referred to as “Tribune corner”. He conducted his column autonomously with little supervision for two years before resigning in 1903. He and Emma relocated back east and bought a home in Cos Cob (Greenwich) Connecticut while their daughter, Alva, attended Harvard. Taylor first wrote a column for the Morning Telegraph called “The way of the World.” Then in 1904, he became one of the contributing editors of Puck, replacing W.C. Whitney who had died that year. During this time back east, he also contributed articles to the New York Sun. Meanwhile, editors at the Tribune met little success in sustaining the same quality of Taylor’s “Line”. James Keeley, a hiring manager at the Tribune, made a lucrative offer to Taylor in hope to lure him back to the paper. Taylor accepted the offer and returned to Chicago in 1909 where he resumed conducting his column without interruption until his death.

The brand of journalism Taylor used and improved upon began in 1895 by Tribune writers, Henry “Butch” White, and later Eugene Field with his “Sharps and Flats” column. Taylor’s satirical verse was a bit more polished than Field’s plain style, and Taylor covered a greater variety of topics. He arranged his column as a mélange of whimsical paragraphs, amusing excerpts from rural papers, and light verse interspersed with submissions from outside contributors; indeed, it was considered an honor to be selected for the “Line.” Many of the selected contributions came from some of the best-known writers of the time who submitted their work using only their initials or pseudonyms such as “Pan” (Keith Preston of The Chicago Daily News) or “Riquarius” (Richard Atwater of The Chicago Evening Post) for example. Submissions came in the form of verse, funny clippings from other newspapers, or absurd observations by “gadders” (tourists) during their travels. Taylor received anywhere from eighty to a hundred letters a day, most addressed simply to “B.L.T.” or “A Line o’ Type or Two” at the Tribune, and he managed to read every one. He also took meticulous care of the column’s editing and layout, correcting all typographical and grammatical errors as well as orchestrating the flow of elements: the upper half of the column contained whimsical philosophy in the form of essay and light verse, followed by pure humorous pieces in the lower half poking fun at the “so-called human race.” His goal was to “send [the reader] away smiling.” Taylor’s editorial opinion and style often conflicted with the Tribune’s editorial policy, but because of columns’ popularity and unique originality, editorial difference was always pardoned; in fact, this editorial disparity was one of the reasons that made the column so appealing.

Taylor set the standard for literary excellence and had a disdain for trite and poor writing (including his own), and he would write about sending all bad writing, or “canned bromides,” off to the “cannery” where each bad piece was placed into a numbered canister. He ended the column using only his initials, “B.L.T,” which served as Taylor’s trademark and were referred to by critics of the day as “the most famous initials in America.” Taylor’s journalistic excellence inspired other great columnists including Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.), nationally known for his “The Conning Tower” column in the New York Post. Simeon Strunsky, columnist for the New York Times, called Taylor “a star of the first magnitude”. By the time of his death, Taylor’s “A Line o’ Type or Two” column was syndicated throughout the country and overseas.

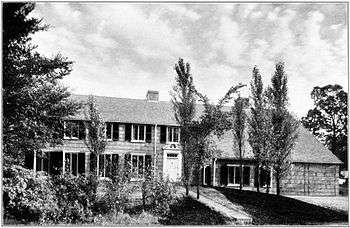

During his employment at the Tribune, Taylor owned a townhouse in downtown Chicago, but later had an estate constructed in Glencoe, Illinois, approximately twenty-five miles north of Chicago on Lake Michigan. The Cape Cod colonial style house was designed by architect Robert Seyfarth[2] of Chicago and was built circa 1916. He was fond of this home[3] and did most of his writing there. The title of one of his books, The East Window, refers to his study.

A man of letters

Apart from journalism, Taylor was an accomplished and recognized humorist, librettist, author, and poet. Taylor was celebrated in his day as one of great American humorists and critics likened him to Josh Billings, Eli Perkins, and Mark Twain. At the height of his celebrity, Taylor was one of the invited guests at Mark Twain’s seventy-fifth birthday held at Monico’s in New York City on December 5, 1905. Novelist Henry Kitchell Webster considered Taylor to be among one of the great letter-writers of the world and classed him with Thomas Gray and British author Edward FitzGerald.

Above all, however, Taylor loved poetry and possessed a remarkable talent for composing it. He wrote predominantly light verse, considered a subgenre of traditional poetry. Light verse is traditionally intended to be humorous, although humor is often a way to approach serious subjects. The use of wordplay, puns, and alliteration are common conventions, and light poetry is typically considered structured form poetry with rhyme schemes. It has been said that writing light verse successfully is the most difficult of all intellectual accomplishments in order for the poet to be taken seriously. Taylor’s wit was not a savage but it often had a bite, and he possessed a keen sense of language and technical skill using rhythmical structures to frame his thought. His verse was often compared to that of Charles Stuart Calverley and William S. Gilbert. In her eulogy at Taylor’s memorial service, Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry, considered Taylor to be in the same league as British poets Frederick Locker-Lampson and Austin Dobson, and American poets Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. and Thomas Bailey Aldrich. Taylor was well read and knew the classics intimately. Horace was a major influence, and Taylor was adept in capturing the essence of his work. Taylor’s love of poetry extended beyond humorous verse, however, as he also enjoyed the work of the more “serious” contemporary poets. In particular, he was fond of Yeats and attended his readings whenever he was in Chicago. In his book of poetry, A Penny Whistle,[4] Taylor dedicates several poems to Yeats. Taylor’s poetry influenced on all levels of society. His poem, “Battle Song” (from Motley Measures), was presented to Edith Carow Roosevelt, which greatly inspired her husband, former president Theodore Roosevelt.

Taylor was a member of several literary groups. One such group referred to themselves as “The Little Room”, the name borrowed from a short story by Madeline Wynne in which a room magically disappears and reappears. The group mimicked the story in that it disappeared and reappeared on Friday afternoons at such places as Chicago’s Auditorium Hotel (now occupied by Roosevelt University) and Fine Arts Building. The group was composed of an eclectic range of distinguished members including reformer Jane Addams, sculptor Lorado Taft, architects Allen Bartlit Pond and Irving Kane Pond, dramatist Anna Morgan, painter Ralph Clarkson, and poet Harriet Monroe. Taylor was also a member of the Cliff Dwellers Club, a club established by novelist Hamlin Garland that consisted of Chicago artists and literary men. The club’s name originated from a novel written by Henry Blake Fuller. Fuller was a close friend of Taylor’s, and played an instrumental role in getting Taylor published.

Taylor not only loved the arts, but mountains, stars, streams, and the north woods. Taylor was an outdoor enthusiast, and his favorite track of wilderness was the Grand Marais area of northern Minnesota, located north of Duluth on the Canadian border, where he enjoyed going on expeditions with his wife and close friends. He was also an avid golfer, and loved spending his leisure time out on the greens.

Chronology of work

Captain Kidd, Coin Collector (1894); Libretto by Bert Leston Taylor and music by Walter H. Lewis. Taylor and Lewis collaborated on three operas

A Political Soldier (1899); Bert Leston Taylor and Edward A. Morris A comedy in three acts.

Ponce de Leon, or the Fountain of Youth; Libretto by Bert Leston Taylor and music by Walter H. Lewis (1900) - Romantic opera comedy. The plot is based on Ponce de Leon and his legendary quest to search for the Fountain of Youth. Performed in Manchester, New Hampshire April 24 and 25, 1900, the opera contains twenty-seven musical numbers including solos, duets, and trios.

The Bilioustine: A Periodical of Knock; published by William S. Lord under the name “the Boy Grafters, at East Aurora, Illinois.” (1901) – The work parodied Elbert Green Hubbard’s Philistine: A Periodical of Protest independently published by his Roycrofters press of East Aurora, New York. Hubbard’s magazine was itself a collection of political satire and whimsy, and sold bound in brown butcher paper because the “meat” was inside." As editor, Taylor referred to himself as Fra McGinnis, a parody on another Hubbard publication, The Fra. The material from Taylor’s Bilioustine originally appeared in the “Line,” and was later published in booklet form. The booklets were also bound in brown paper and twine after Hubbard’s Philistine, and they sold at various stores and markets throughout Chicago, Denver, and Buffalo.

The BOOK Booster: A Periodical of Puff; published by William S. Lord (1901) – A burlesque on the Bookman, which was a periodical promoting new books. Taylor parodied the sensationalizing techniques used by the publishing industry to attract prospective readers, regardless of the quality of the work. Taylor took the whimsical pseudonym “Mr. Criticus Flub-Dubbe ” as editor, and the book used the name “Josh. Gosh & Company” as publisher. Most of the material was originally published in the “Line.”

The Explorers; published by M. Witmark & Sons (1901) – Romantic and comical opera in two acts. Gustav Luders was originally contracted to compose the music to Taylor’s libretto but fell behind schedule due to an extensive honeymoon with his wife in Europe. Walter Lewis replaced Luders, and the opera opened June 30 at the Dearborn Theatre in Chicago on one of the hottest nights of the summer season – the inside temperatures were reported at being 100 degrees. The plot of the musical comedy concerns the misadventures of a German polar explorer, Professor S. Max Nix. The opera is in three parts; the first of which opens in Madagascar where Burdock Root, supplier of peroxide, meets explorer Max Nix. The latter descends in a balloon and explains that he’s on his way from the South Pole to the U.S., where he intends to lecture about it. Nix falls in love with a portrait of circus performer, Maizie Fields of Iowa, shown to him by Root. The act ends with Nix ascending back into his balloon in pursuit of her. The second act opens in a hotel in Chicago. Burdock Root is in financial distress and passes himself off as Max Nix, who is not exposed until the third act set in Chicago’s Lincoln Park during winter when the irate Nix unmasks Root. When the opera went on the road to other parts of the country (Boston, New York) there were some changes in names, plot, and location. For example, the last scene takes place on circus grounds instead of Lincoln Park.

Line-o’-Type Lyrics; published by William S. Lord (1902) – Humorous verse and parodies that has been compared with Bret Harte, Thomas Hood, and Charles Stuart Calverley. Taylor uses many formal styles of poetry including the ballade, sonnet, and rondeau.[5]

Monsieur d’En Brochette,[6] Being an Historical Account of Some of the Adventures of Huevos Pasada Par Agua, Marquis of Pollio Grille, Count of Pate de Foie Gras, and Much Else Besides; published by Keppler & Schwarzmann (1905) – Co-authored with Arthur Hamilton Folwell and John Kendrick Bangs, the latter being an editor for Puck. Illustrated by the Australian born painter Frank A. Nankivell. The book concerns itself with the comical misadventures of Robert Gaston.

The Log of the Water Wagon; Or, The Cruise of the Good Ship “Lithia”; published by H.M. Caldwell Company (1905) – Co-authored with William Curtis Gibson and with illustrations by L.M. Glackens. Humorous excerpts from the “Lithia’s” ship log depicting its intoxicating adventures. The book is full of jokes about drinking and pokes fun at temperance.

Extra Dry; Being Further Adventures of the Water Wagon; published by G.W. Dillingham Company (1906) – Co-authored with William Curtis Gibson and with illustrations by L.M. Glackens. Continuing amusements about drinking.

Cornucopia; (1907) – Bert Leston Taylor and Franklin P. Adams. A dramatic composition in two acts.

The Charlatans; published by The Bobbs-Merrill company (1906) – Romantic fiction with illustrations by George Brehm. The novel is a love story with a layering of satire against the background of musical education, and includes dark moments of betrayal and a tragic suicide. The plot concerns a Wisconsin farm girl, named Hope Winston, who possesses natural musical genius and comes to Chicago to perfect her craft. Taylor uses select Chicago celebrities and institutions (including the “Little Room”) as a backdrop, and these subjects are often the target of satire. Taylor’s satire is particularly harsh as it concentrates on the bogus methods of teaching music at some of the Chicago best-known schools. Taylor invents villain Rudolph Erdmann and his prestigious “Colossus Conservatory of Music,” where he dupes young, aspiring musicians, regardless of talent, solely for their money. However, it’s often much more than money that is lost – destroyed hopes and dreams are the greatest casualty.

A Line-o’-Verse or Two; published by Reilly & Britton Co. (1911) – Light verse. Originally published in the Chicago Tribune and Puck, this collection is considered to represent Taylor’s best from this period.[7]

Campi golfarii Romae Antiqvae (The Links of Ancient Rome);[8] published privately by the “Brothers of the Book Miscellanea” (1912) – Humorous verse about golf. Introduction and English verses written by Taylor, and Latin verses, notes, and title page written by Payson Sibley Wild. Edited by Lawrence Conger Woodworth. Payson Wild was a classical scholar and one of Taylor’s favorite contributors to the “Line.”

The Pipesmoke Carry;[9] published by Reilly & Britton Co. (1912) – Decorations (illustrations) by C.B. Falls (Charles Buckles). Taylor's twenty-two essays describe his love for the northern wilderness. Through vivid and simple prose, Taylor narrates a true sense of the woods, its tonic, and its poetry. The term “carry” from the title refers to portage, and “pipesmoke” is “a certain tobacco known by men of the forest, that when burned summons memories of days frantic of wind and rain, days of long excursions, filled with the odor of balsam and sun burned grass, little adventures, rare acquaintances made by chance.”

Posthumous publications

The Cliff Dwellers; In Memory of Bert Leston Taylor (B.L.T.); published by W.M. Hill under the auspices of the Cliff Dwellers and the Chicago Tribune (1922) – A program and records of Taylor’s memorial service held in the Blackstone Theater on March 27, 1921.

A Penny Whistle; Together With the Babette Ballads; published by Alfred A. Knopf (1921) – This Knopf publication represents the first posthumous title, which had a second printing in 1927. This collection of verse originally published in the “Line” over an eight-year period is considered to represent Taylor’s best. The book also contains fifteen poems written for his daughter, Babette (Barbara Whitney Dunn) Taylor. Foreword by Franklin Pierce Adams. Taylor was very much fond of William Butler Yeats, and six poems are in this volume are dedicated to Yeats and Ireland. Taylor gives also gives praise to George Bernard Shaw and his play, Major Barbara, and to Rudyard Kipling and Alfred Noyes in the poem, “The Dardanelles.” The Babette Ballads were written after William S. Gilbert’s book of humorous poetry, The Bab Ballads. Among the Babette Ballads, the poem “The Horoscope” references “Zariel, the Astrologer,” who represents Taylor’s long-time friend and collaborator, Walter Lewis. Taylor had the manuscript, book title, and order of poems arranged for publication prior to his death.

The So-Called Human Race; published by Alfred A. Knopf (1922) – The second posthumous collection contains essays, light verse, and miscellaneous material originally published in the “Line.” Henry Blake Fuller, Chicago novelist, critic, and close friend of Taylor, wrote the introduction and edited the material in a similar pattern that Taylor would have used when he conducted the “Line.” The book is blended with witty limericks, whimsical fables, politically charged satirical quips, and absurd clippings from rural newspapers around the country.[10]

The Well in the Wood;[11] published by Alfred A. Knopf (1922) – Children’s book. Originally published in 1904 by The Bobbs-Merrill Co., this 1922 publication represents the third posthumous publication in the series of Taylor’s work by Knopf. Illustrations by Fanny Y. Cory, who illustrated many books including the 1902 publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice's Adventures in Wonderland as well as several books by L. Frank Baum, author of The Wizard of Oz. Taylor’s wife, Emma Bonner Taylor, wrote the musical pieces that appear throughout the book. Compared to Alice in Wonderland, Taylor’s The Well in the Wood was hailed a children’s classic at its second Knopf printing. The title comes from the old adage “ truth lies at the bottom of a well.” Tiffany Blake commented that Taylor used the same genius in writing this whimsical children story as displayed in making the “Line” different than any other newspaper column in history. Taylor wrote the book for his daughter, Alva, who was seven at the time – she undoubtedly was the first person to give the manuscript a nod for publication.

A Line o’ Gowf or Two; published by Alfred A. Knopf (1923) – The third posthumous collection contains verse and humorous essays on golf. Introduction by Charles “Chick” Evans, Jr., who was a leading amateur golfer and won the U.S. Open and the U.S. Amateur in a single year. Evans was also a golfing friend of Taylor’s. Taylor loved golf and probably enjoyed writing about it as much as he loved playing the game. It was his most cherished hobby throughout the last years of his life, although he did not play competitively as demonstrated by the fact that he never kept score. He said that he played golf not because he liked it, but that it kept him young, and he needed to stay young in order to keep the “youthfulness” in his writing. While the book is whimsical, it also offers practical advice on how to play the game. For example, his sage advice to “look at the hole and not the ball when putting” gained a great deal of attention in the golfing community and it the current advice used today. Excerpts from his book appeared in such magazines as Golf Illustrated and Golfers Magazine. The collection was edited by his wife, Emma Taylor.

The East Window, and The Car Window; published by Alfred A. Knopf (1924) – The fifth volume of posthumous work published by Knopf is a collection of essays that originally appeared in the middle portion (about two-thirds down) of the “Line.” Introduction by Henry Blake Fuller, and foreword by James Rowland Angell, former president of Yale. Illustrations by C.B. Falls (Charles Buckles). “The East Window” section of the book is a collection of short, meditative essays on music, painting, literature, nature, travel, domestic life as well as various whimsical subjects., including clouds, trilliums, books, expeditions into the woods, stars, and poetry. He touched upon many subjects: the philosophies of Hardy, Thoreau, and Yeats; of Orion hanging low in the west; of saxifrage, anemone and trillium; and of Brahms, Mansfield Park, election night, good furniture, and the trivialities of existence. “The Car Window” section is a series describing Taylor’s trip through the West and Canada on his way to San Diego in 1919, where he worked briefly for The Union. He wrote the essays in the course of two years facing Lake Michigan from the east window of his Glencoe estate. Here is an excerpt from the book reflecting Taylor’s thoughts on poetry: “Much of the poetry I like classifies simply as music; it is not to be turned inside out and scrutinized for a meaning. If it produces an effect similar to that which a page of beautiful music produces, it has justified itself, and there is nothing to argue about.”

Motley Measures; published by Alfred A. Knopf (1927) – Originally published in 1913 by Laurentian Publishers, a group that wanted to publish books by distinctive Chicago authors. Their first title was The Beginning of Grand Opera in Chicago, by music critic Karleton Hackett. The bulk of the verses in this collection first appeared in the Line. Foreword by Ring Lardner, the American sports columnist and short-story writer. Described as a book of light verse commenting upon human follies, frailties, and foibles, but with an unfailing sympathy and greathearted tolerance – it ranges from nonsense verse of Edward Lear to the elegance of Frederick Locker-Lampson and the Fragonard-like magic of Austin Dobson. Taylor’s light verse covers a multitude of whimsies, parodies, satires, and lampoons. Some of the poems are topical and satirical, but there are also a few nature poems about the woods and waters that appealed to Taylor.

Other accomplishments

The Last of the Great Scouts; Published by The Duluth Press Publishing Company (1899). While Taylor was in Duluth, he ghostwrote this book for Helen Cody Wetmore, sister to William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, which recounted Buffalo Bill’s infamous exploits.

Bert Leston Taylor died of pneumonia in his townhouse home on East Chestnut Street in Chicago, March 19, 1921 at 5:45 a.m. He was fifty-four. The funeral took place at the Fourth Presbyterian Church, and the memorial service was held at the Blackstone Theatre, both in Chicago. 1,300 people attended the memorial service at the theatre, which was its capacity. Hundreds remained outside. The Flonzaley Quartet (members were MM. Betti, Pochon, Bailly, and D’Archambeau) performed romanza and allegretto movements from Brahms’ C minor quartet, which was performed at the last concert Taylor attended.

He was survived by his wife, Emma, and his two children, Alva Thoits Taylor (24) and Barbara Leston Taylor (5).

References

- ↑ "In Memory of Bert Leston Taylor: Program and Records of a Public Meeting Held in the Blackstone Theatre March 27, 1921" (1921) The Cliff Dwellers, Chicago

- ↑ Robert E. Seyfarth Robert Seyfarth, Architect. Accessed 20 June 2010

- ↑ Jewett, Eleanor (c. March 1921) "Art and Architecture - Cape Cod Colonial Seen in B.L.T.'s Home", The Chicago Tribune

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor (1921) A Penny Whistle: Together with the Babette Ballads, A.A. Knopff, New York OCLC 1601524

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor (1902) Line-o’-Type Lyrics, William S. Lord, Evanston, IL OCLC 9841814

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor, Arthur Hamilton Folwell, John Kendrick Bangs (1905) Monsieur d’En Brochette, Keppler & Schwarzmann, NY

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor (1911) A Line-o’-Verse or Two, Reilly & Britton Co., Chicago

- ↑ Payson Sibley Wild; Bert Leston Taylor; Laurence Conger Woodworth (1912) Campi golfarii Romae Antiqvae, In linea Sartoris, Chicago

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor (1912) The Pipesmoke Carry, Reilly & Britton Co., Chicago

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor (1922) The So-Called Human Race, Alfred A. Knopf, New York

- ↑ Bert Leston Taylor (1922) The Well in the Wood, Alfred A. Knopf, New York

External links

- biography of Taylor by his grandson Anthony Taylor Dunn

- Works by Bert Leston Taylor at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bert Leston Taylor at Internet Archive

- Works by Bert Leston Taylor at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Poem "The Passionate Professor"

List of American Poets

|