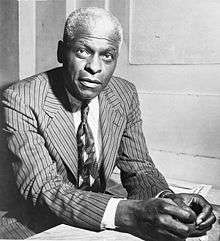

Benjamin Mays

| Benjamin Mays | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Benjamin Elijah Mays August 1, 1894 Ninety Six, South Carolina |

| Died |

March 28, 1984 (aged 89) Atlanta, Georgia |

| Monuments |

Monuments

• Benjamin E. Mays High School • The Mays Hall of Howard University • Benjamin Mays Center at Bates College • Benjamin E. Mays International Magnet School in St. Paul, Minnesota |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Movement | African-American Civil Rights Movement, Peace movement |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Denomination | Baptist (Progressive National Baptist Convention) |

| Spouse(s) |

Ellen Harvin (m.1920-1923; her death) Sadie Gray (m.1926) |

Benjamin Elijah Mays (August 1, 1894 – March 28, 1984) was an American Baptist minister, activist, humanitarian, and leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights, and the progression of African American rights in America. He was active working with world leaders, such as John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and John D. Rockefeller, in improving the social standing of minorities in politics, education, and business.

Mays was also a significant mentor to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and King considered him, his "spiritual mentor" and "intellectual father."[1] Mays was among the most articulate and outspoken critics of segregation before the rise of the modern civil rights movement in the United States. Mays became a civil rights activist early in his career, by publishing a dissertation entitled The Negro's Church, the first sociological study of the black church in the United States. Soon after in 1938, he published The Negro's God as Reflected in His Literature, both publications have heavily contributed to the study of religion, and sociology.

He served as the president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia from 1940 to 1967. He revived the college from serious financial burden, which was at one point so prominent that the entire college's finances and endowment was given to Atlanta University to manage. Mays took the endowment back, raised the standards for endowment collection and allocation and by the end of his term more than quadrupled the endowment. He launched a 27-year tenure that brought the college into international prominence. He improved the working conditions for the staff and quality of the faculty, secured a Phi Beta Kappa chapter and controlled enrollment levels during wartime America. As president, he met hundreds of national and international leaders and served as a trusted advisor to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter. He was appointed by President Truman to the Mid-Century White House Conference on Children and Youth. When Pope John XXIII died in 1963, President Kennedy sent Mays and his Vice President to represent the United States at the funeral in Rome, Italy.

Originally enrolling in Virginia Union University, he moved north to attend Bates College in Maine, where he obtained his B.A. in 1920, as a Phi Beta Kappa graduate. He began his activist career as a pastor in the Shiloh Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. He then entered the University of Chicago as a graduate student, earning an M.A. in 1925, and a Ph.D. in Religion in 1935. After he attained his Doctorate he went on to teach at Morehouse College, where he taught mathematics and was their debate coach. In 1934, he was appointed dean of the School of Religion at Howard University.

He served as president of the Atlanta Board of Education, has received 56 honorary degrees,and has published nearly 2000 articles and nine books.[1]

Early life

Benjamin Elijah Mays was born in 1894 in the small town of Ninety Six, South Carolina, the youngest of eight children; his parents were tenant farmers and former slaves. Given this history and its impact on the development of his parents, Mays’ childhood was instrumental in creating the political endeavors that he would later pursue. When he was little, a white mob approached his home on horseback with guns drawn, and forced his father to remove his hat and bow before them repeatedly. These group of men were associated with the Phoenix Election Riot which began four years after his birth. He grew up in an area where lynching was commonplace and was forced into segregated areas around his community. When he was a child, he excelled in his studies and had "an insatiable desire to get an education."[2] During his childhood, he was often in conflict with his father, who thought his time would be better utilized working on the family's farm. His mother, was a constant support mechanism in his life but could not read or write.[3]

Education

Early schooling

He attended the Brick House School in Epworth, a Baptist-sponsored school, Mays left Epworth to attend the High School Department at South Carolina State College in Orangeburg, South Carolina. He graduated as Valedictorian at the age of 22.

Collegiate career

After spending a year at Virginia Union University, but grew weary of the segregated south and needed a place that ensured physical and emotional safety for him to pursue his studies. He moved north to attend Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. He was one of few black students at Bates, but he encountered little racial prejudice at the college and felt as through he was an equal. He said, of his time at Bates, "For the first time...I felt at home in the universe."[2] While at Bates, he was captain of the debate team and played on the football team. Shortly after graduating from Bates, he married his first wife, Ellen Harvin, who died in 1923, following an operation.

He graduated from the college in 1920, with a B.A., as a Phi Beta Kappa graduate. He then entered the University of Chicago as a graduate student, earning an M.A. in 1925 and a Ph.D. in the School of Religion in 1935. His education at Chicago was interrupted several times: he was ordained a Baptist minister in 1922 and accepted a pastorate at the Shiloh Baptist Church of Atlanta, then later taught at Morehouse and at South Carolina State College. While teaching at South Carolina State College, he met his second wife, Sadie Mays and married in 1926. After their marriage, they moved to Tampa, Florida to serve with the Tampa Urban League.

Early religious career

While in graduate school, Mays worked as a Pullman Porter. He also worked as a student assistant to Dr. Lacey Kirk Williams, pastor of Olivet Baptist Church in Chicago and President of the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc.

Career

In 1928, he served as National Student Secretary of the YMCA in Atlanta but took a leave to conduct a national study of African-American churches from 1928 to 1930. In 1933, he wrote his first book was published, The Negro's Church with Joseph Nicholson.This was the first sociological study of the black church in the United States. Four years later in 1938, he published The Negro's God as Reflected in His Literature.

He went on to write numerous articles on race, religion, and the African-American Civil Rights Movement.

Mays accepted the position of dean of the School of Religion at Howard University in Washington, D.C. in 1934. During his six years as dean, Mays traveled to India, where, at the urging of Howard Thurman, a fellow professor at Howard, he spoke at some length with Mahatma Gandhi. Numerous publications Mays has produced reference this experience as a contributing factor to his civil rights ideology and practice.[4]

Morehouse College

His most profound movements in the African-American Civil Rights Movement was when he was appointed the president of Morehouse College, in 1940. When Dr. Mays took over as president of Morehouse, the school was in terrible financial straits, and they had not had sound leadership since Dr. John Hope was president in the early 1900s. For those reasons, Dr. Mays accepted the job offer, and he took it as his duty to revive Morehouse.[5] In 1933, Morehouse was doing so poorly financially that it had allowed Atlanta University to take over its financial direction and budget. Within two years of his presidency, Dr. Mays was so successful that he was able to regain control of Morehouse's finances.[6] Dr. Mays had a few goals going into his presidency that he believed he must accomplish. At the top of his list was the need to hire more teachers, and to pay those teachers a better salary. To do that, Dr. Mays sought to be more strict in the collection of student fees, and he wanted to increase Morehouse's endowment from $1,114,000. Mays' fee collecting earned him the nickname "Buck Benny", and he more than quadrupled the endowment that he inherited by the end of his 27-year tenure.[6]

Faculty expansion

All of Dr. Mays' achievements and goals for Morehouse College went hand in hand with one another. To manufacture the graduates he so desired, he needed financial security and a good faculty. Thus, while maintaining financial security at Morehouse, Dr. Mays also desired and succeeded at continuing the esteemed tradition of producing Morehouse Men. A Morehouse Man was a highly educated and dedicated to service black professional. Specifically, Dr. Mays wanted his Morehouse Men to be physicians, lawyers, and ministers.[7] In his first speech to an incoming freshman class in 1940, Dr. Mays said, "If Morehouse is to continue to be great; it must continue to produce outstanding personalities."[5] However, it was not enough for Dr. Mays' students to be successful professionals. In addition to their success, he believed that they must be Christians who gave back to the black community.[7] As president, he met hundreds of national and international leaders and served as a trusted advisor to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter. He was appointed by President Truman to the Mid-Century White House Conference on Children and Youth. When Pope Paul 23rd died in 1963, President Kennedy sent Mays and his Vice President to represent the United States at the funeral in Rome, Italy.[4]

Martin Luther King Jr.

His most famous student at Morehouse was someone who benefitted deeply from Dr. Mays' educational and religious philosophies - Martin Luther King Jr. The two developed a close relationship that continued until King's death in 1968. Dr. King referred to Dr. Mays as his "Spiritual Mentor", and he saw in Dr. Mays "the ideal of what I [King] wanted a minister to be." Mays delivered the eulogy for King at his funeral.[8]

Mays, in his eulogy for Martin Luther King Jr. at Morehouse College in 1968 noted King's time in history by stating:

"He was not ahead of his time. No man is ahead of his time. Every man is within his star, each in his time. Each man must respond to the call from God in his life time and not in somebody else's' time."[9]

Mays emphasized two themes throughout his life: the dignity of all human beings and the gap between American democratic ideals and American social practices. Those became key elements of the message of King and the American civil rights movement. Mays explored these themes at length in his book Seeking to Be a Christian in Race Relations, published in 1957.

Mays gave the benediction at the close of the official program of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.[10]

Atlanta Board of Education

After his retirement in 1967 from Morehouse, Mays was elected president of the Atlanta Public Schools Board of Education, where he supervised the peaceful desegregation of Atlanta's public schools. He published two autobiographies, Born to Rebel (1971), and Lord, the People Have Driven Me On (1981). In 1982, he was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP.[11]

Death

Mays died in Atlanta on March 28, 1984. He was entombed on the campus of Morehouse College. His wife Sadie is entombed beside him. He has received 56 honorary degrees,and has published nearly 2000 articles and nine books.[1]

Legacy

Benjamin E. Mays High School in Atlanta, The Mays Hall of Howard University (where the School of Divinity is housed), and the Benjamin Mays Center at Bates College are named in Mays' honor, as well as Benjamin E. Mays International Magnet School in St. Paul, Minnesota.[12]

Mays was a member of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Benjamin Mays on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[13]

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Morehouse College | Benjamin E. Mays Bio". www.morehouse.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- 1 2 "Dr. Benjamin E. Mays | MMUF". www.mmuf.org. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ↑ Voices of Black South Carolina: Legend & Legacy, by Damon L. Fordham, pages 125-126

- 1 2 "The Life of Benjamin Elijah Mays".

- 1 2 Jelks, Randal Maurice. Benjamin Elijah Mays, Schoolmaster of the Movement : A Biography. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 5 November 2014.

- 1 2 Mays, Benjamin E.. Born to Rebel : An Autobiography. Athens, GA, USA: University of Georgia Press, 2003. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 5 November 2014.

- 1 2 Roper, John Herbert. Magnificent Mays : A Biography of Benjamin Elijah Mays. Columbia, SC, USA: University of South Carolina Press, 2012. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 5 November 2014.

- ↑ "King Encyclopedia," http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/kingweb/about_king/encyclopedia/mays_benjamin.htm.

- ↑ "Quote of the Day: Benjamin E. Mays on Martin Luther King Jr.". The Root. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ↑ http://www.criticalpast.com/video/65675029520_Invocation_Lincoln-Memorial_March-on-Washington

- ↑ NAACP Spingarn Medal

- ↑ Benjamin E. Mays International Magnet School

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

Works

- The Negro Church New York: Institute of Social and Religious Research (1933), sociological survey of rural and urban black churches in 1930; with Joseph W. Nicholson.

- The Negro's God as reflected in his literature (Boston: . Chapman & Grimes, Incorporated, 1938)

- "The Moral Aspects of Segregation Decisions." The Journal of Educational Sociology (1956): 361-366. in JSTOR

- "The Significance of the Negro Private and Church-Related College." Journal of Negro Education (1960): 245-251. in JSTOR

- Seeking to be Christian in race relations Friendship Press, 1964.

- Disturbed about man (John Knox Press, 1969)

- Born to Rebel: An Autobiography. New York: Scribners, 1971.

Further reading

- Randal Maurice Jelks, Benjamin Elijah Mays: Schoolmaster of the Movement: A Biography. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Thomas, Rhondda R. & Ashton, Susanna, eds. (2014). The South Carolina Roots of African American Thought. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press."Benjamin Elijah Mays (1894-1984)," p. 217-221.

External links

- Peter A. Kuryla, "Benjamin Elijah Mays," New Georgia Encyclopedia, www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/

|