Benesi–Hildebrand method

The Benesi–Hildebrand method is a mathematical approach used in physical chemistry for the determination of the equilibrium constant K and stoichiometry of non-bonding interactions. This method has been typically applied to reaction equilibria that form one-to-one complexes, such as charge-transfer complexes and host–guest molecular complexation.

The theoretical foundation of this method is the assumption that when either one of the reactants is present in excess amounts over the other reactant, the characteristic electronic absorption spectra of the other reactant will be transparent in the collective absorption/emission range of the reaction system.[1] Therefore, by measuring the absorption spectra of the reaction before and after the formation of the product and its equilibrium, the association constant of the reaction can be determined.

History

This method was first developed by Benesi and Hildebrand in 1949,[2] as a means to explain a phenomenon where iodine changes color in various aromatic solvents. This was attributed to the formation of an iodine-solvent complex through acid-base interactions, leading to the observed shifts in the absorption spectrum. Following this development, the Benesi-Hildebrand method has become one of the most common strategies for determining association constants based on absorbance spectra.

Derivation

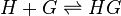

To observe one-to-one binding between a single host (H) and guest (G) using UV/Vis absorbance, the Benesi–Hildebrand method can be employed. The basis behind this method is that the acquired absorbance should be a mixture of the host, guest, and the host-guest complex.

With the assumption that the initial concentration of the guest (G0) is much larger than the initial concentration of the host (H0), then the absorbance from H0 should be negligible.

The absorbance can be collected before and following the formation of the HG complex. This change in absorbance (ΔA) is what is experimentally acquired, with A0 being the initial absorbance before the interaction of HG and A being the absorbance taken at any point of the reaction.

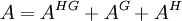

Using the Beer–Lambert law, the equation can be rewritten with the absorption coefficients and concentrations of each component.

Due to the previous assumption that [G]0 >> [H]0, one can expect that [G] = [G]0. Δε represents the change in value between εHG and εG.

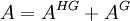

A binding isotherm can be described as "the theoretical change in the concentration of one component as a function of the concentration of another component at constant temperature." This can be described by the following equation:

By substituting the binding isotherm equation into the previous equation, the equilibrium constant Ka can now be correlated to the change in absorbance due to the formation of the HG complex.

Further modications results in an equation where a double reciprocal plot can be made with 1/ΔA as a function of 1/[G]0. Δε can be derived from the intercept while Ka can be calculated from the slope.

Limitations

In most cases, the Benesi–Hildebrand method will give excellent linear plots and reasonable values for K and ε. However, various problems arising from experimental data have been noted from time to time. Some of these issues include: different values of ε with different concentration scales,[3] lack of consistency between the Benesi–Hildebrand values and those obtained from other methods (e.g. equilibrium constants from partition measurements[4]), and zero and negative intercepts.[5]

Concerns have also surfaced over the accuracy of the Benesi–Hildebrand method as certain conditions cause these calculations to become invalid.

For instance, the reactant concentrations must always obey the assumption that the initial concentration of the guest (G0) is much larger than the initial concentration of the host (H0). In the case when this breaks down, the Benesi–Hildebrand plot deviates from its linear nature and exhibits scatter plot characteristics.[6]

Also, in the case of determining the equilibrium constants for weakly[7] bound complexes, it is common for the formation of 2:1 complexes to occur in solution. It has been observed that the existence of these 2:1 complexes generate inappropriate parameters that significantly interfere with the accurate determination of association constants. Due to this fact, one of the criticisms of this method is the inflexibility of only being able to study reactions with 1:1 product complexes.

Another limitation of the Benesi–Hildebrand method and most of its other methods that should be considered is the dependency of K and ε. Typically, one single parameter (K or ε) and the product Kε always appears in either the slope or the intercept . Thus, only one parameter can be evaluated independently of the other.

Modifications

Although initially used in conjunction with UV/Vis spectroscopy, many modifications have been made that allow the B–H method to be applied to other spectroscopic techniques involving fluorescence,[8] infrared, and NMR.[9]

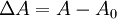

Modifications have also been done to further improve the accuracy in the determination of K and ε based on the Benesi–Hildebrand equations. One such modification was done by Rose and Drago.[10] The equation that they developed is as follows:

Their method relied on a set of chosen values of ε and the collection of absorbance data and initial concentrations of the host and guest. This would thus allow the calculation of K−1. By plotting a graph of εHG versus K−1, the result would be a linear relationship. When the procedure is repeated for a number of varying concentrations and plotted on the same graph, the lines will intersect at a point giving the optimum value of εHG and K−1. However, some problems have surfaced with this modified method as some examples displayed an imprecise point of intersection[11] or no intersection at all.[12]

More recently, another graphical procedure[13] has been developed in order to evaluate K and ε independently of each other. This approach relies on a more complex mathematical rearrangement of the Benesi–Hildebrand method but has proven to be quite accurate when compared to standard values.

See also

References

- ↑ Anslyn, Eric (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- ↑ Benesi H, Hildebrand J (1949). "A Spectrophotometric Investigation of the Interaction of Iodine with Aromatic Hydrocarbons" J. Am. Chem. Soc. 71(8): 2703–07.

- ↑ Scott R (1956) "Some comments on the Benesi–Hildebrand equation" Rec. Trav. Chim 75: 787–89.

- ↑ McGlynn S (1958) "Energetics of Molecular Complexes" Chem. Rev. 58: 1113–56.

- ↑ Hanna M, Ashbaugh A (1964) "Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Molecular Complexes of 7,7,8,8-Tetracyanoquinodimethane and Aromatic Donors" J. Phys. Chem 68: 811–16.

- ↑ Qureshi P, Varshney R, Singh S (1994). "Evaluation of є for the p-dinitrobenzene-aniline complexes by the Scott equation. Failure of the Benesi–Hildebrand equation" Spectrochim. Acta A. 50(10): 1789–90.

- ↑ Arnold B, Euler A, Fields K, and Zaini R (2000). "Association constants for 1,2,4,5-tetracyanobenzene and tetracyanoethylene charge-transfer complexes with methyl-substituted benzenes revisited" J. Phys. Org. Chem. 13: 729–34.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay M, Banerjee D, Koll A, Mandal A, Filarowski A, Fitzmaurice D, Das R, Mukherjee S (2005). "Excited state intermolecular proton transfer and caging of salicylidine-3,4,7-methyl amine in cyclodexrins" J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 175(2–3): 94–99.

- ↑ Wong K, Ng S (1975). "On the use of the modified Benesi-Hildebrand equation to process NMR hydrogen bonding data" Spectrochimica Acta A 32: 455–456.

- ↑ Rose N, Drago R (1959). "Molecular Addition Compounds of Iodine. I. An Absolute Method for the Spectroscopic Determination of Equilibrium Constants" J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81: 6138–6141.

- ↑ Drago R, Rose N (1959). "Molecular Addition Compounds of Iodine. II. Recalculation of Thermodynamic Data on Lewis Base-Iodine Systems Using an Absolute Equation" J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81: 6141–6145.

- ↑ Seal B, Mukherjee A, Mukherjee D (1979). "An Alternative Method of Solving the Rose-Drago Equation for the Determination of Equilibrium Constants of Molecular Complexes" Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 52(7): 2088–2090.

- ↑ Seal B, Sil H, Mukherjee D (1982). "Independent determination of equilibrium constant and molar extinction coefficient of molecular complexes from spectrophotometric data by a graphical method" Spectrochim. Acta A. 38(2): 289–292.

![{\Delta}A=\epsilon^{HG}[HG]b+\epsilon^{G}[G]b-\epsilon^{G}[G]_0b\,](../I/m/bac7cbc495eef9db9381b099141b2afa.png)

![{\Delta}A={\Delta}\epsilon[HG]b\,](../I/m/4571d926bf6cd6ee90f3fa92a38753cf.png)

![[HG] = \frac{[H]_0K_a[G]}{1+K_a[G]}](../I/m/ab194e325ea205ddee294aa9c982e738.png)

![{\Delta}A=b{\Delta}\epsilon{\frac{[H]_0K_a[G]_0}{1+K_a[G]_0}}](../I/m/92f7644622e73665ae442943b2f1f0a1.png)

![\frac{1}{{\Delta}A}=\frac{1}{b{\Delta}\epsilon[G]_0[H]_0K_a} +\frac{1}{b{\Delta}\epsilon[H]_0}](../I/m/84e225b719eae8d837a30d6aefda8e02.png)

![K^{-1}=\frac{A}{\epsilon_{HG}} - [H]_0 - [G]_0 + \frac{C_HC_G}{A}\epsilon_{HG}](../I/m/f0b9878c25855536bd60bf0e6ab3369c.png)