Disciple whom Jesus loved

The phrase the disciple whom Jesus loved (Greek: ὁ μαθητὴς ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς, ho mathētēs hon ēgapā ho Iēsous) or, in John 20:2, the Beloved Disciple (Greek: ὃν ἐφίλει ὁ Ἰησοῦς, hon ephilei ho Iēsous) is used six times in the Gospel of John,[1] but in no other New Testament accounts of Jesus. John 21:24 states that the Gospel of John is based on the written testimony of this disciple.

Since the end of the 1st century, the Beloved Disciple has been commonly identified with John the Evangelist.[2] Scholars have debated the authorship of Johannine literature (the Gospel of John, First, Second, and Third epistles of John, and the Book of Revelation) since at least the third century, but especially since the Enlightenment. According to Stephen L Harris, this view is rejected by modern scholars.[3]

Sources

_-_James_Tissot.jpg)

The disciple whom Jesus loved is referred to, specifically, six times in John's gospel:

- It is this disciple who, while reclining beside Jesus at the Last Supper, asks Jesus who it is that will betray him, after being requested by Peter to do so.[Jn 13:23-25]

- Later at the crucifixion, Jesus tells his mother, "Woman, here is your son", and to the Beloved Disciple he says, "Here is your mother."[Jn 19:26-27]

- When Mary Magdalene discovers the empty tomb, she runs to tell the Beloved Disciple and Peter. The two men rush to the empty tomb and the Beloved Disciple is the first to reach the empty tomb. However, Peter is the first to enter.[Jn 20:1-10]

- In John 21, the last chapter of the Gospel of John, the Beloved Disciple is one of seven fishermen involved in the miraculous catch of 153 fish.[Jn 21:1-25] [4]

- Also in the book's final chapter, after Jesus implies the manner in which Peter will die, Peter sees the Beloved Disciple following them and asks, "What about him?" Jesus answers, "If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you? You follow Me!"[John 21:20-23]

- Again in the gospel's last chapter, it states that the very book itself is based on the written testimony of the disciple whom Jesus loved.[John 21:24]

The other Gospels do not mention anyone in parallel circumstances who could be directly linked to the Beloved Disciple. For example, in Luke 24:12, Peter runs alone to the tomb. Mark, Matthew and Luke do not mention any one of the twelve disciples having witnessed the crucifixion.

There are also two references to an unnamed "other disciple" in John 1:35-40 and John 18:15-16, which may be to the same person based on the wording in John 20:2.[5]

Identity

John the Apostle

The closing words of John's Gospel state explicitly concerning the Beloved Disciple that "It is this disciple who testifies to these things and has written them, and we know that his testimony is true."[21:24]

Eusebius writing in the 4th century recorded in his Church History a letter which he believed to have been written by Polycrates of Ephesus (c. 130s–196) in the 2nd century. Polycrates believed that John was the one who reclined upon the bosom of the Lord; suggesting an identification with the Beloved Disciple:

John, who was both a witness and a teacher, who reclined upon the bosom of the Lord, and, being a priest, wore the sacerdotal plate. He fell asleep at Ephesus.[6]

Augustine of Hippo (354 - 430 A.D.) also believed that John was the beloved disciple, in his Tractates on the Gospel of John.[7]

The assumption that the Beloved Disciple was one of the Twelve Apostles is that he was apparently present at the Last Supper which Matthew and Mark state that Jesus ate with the Twelve.[8] Thus the most frequent identification is with John the Apostle, who would then be the same as John the Evangelist.[9] Merril F. Unger presents a case for this by a process of elimination.[10]

| Part of a series of articles |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Communities |

| Related literature |

| See also |

Nevertheless, while some modern academics continue to share the view of Augustine and Polycrates,[11][12] a growing number do not believe that John the Apostle wrote the Gospel of John or indeed any of the other New Testament works traditionally ascribed to him, making this linkage of a 'John' to the beloved disciple difficult to sustain.[13]

Lazarus

The Beloved Disciple has also been identified with Lazarus of Bethany, based on John 11:5: "Now Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus".[14] John 11:3 is also relevant: "Therefore his sisters sent unto him, saying, Lord, behold, he whom thou lovest is sick." Also relevant is the fact that the character of the Beloved Disciple is not mentioned before the raising of Lazarus (Lazarus being raised in John 11, while the Beloved Disciple is first mentioned in John 13).

Frederick Baltz[15] asserts that the Lazarus identification, the evidence suggesting that the Beloved Disciple was a priest, and the ancient John tradition are all correct. Baltz says the family of the children of Boethus, known from Josephus and Rabbinic literature, is the same family we meet in the eleventh chapter of the Gospel: Lazarus, Martha, and Mary of Bethany. This is a beloved family, according to John 11:5. The historical Lazarus was Eleazar son of Boethus, who was once Israel’s High Priest, and from a clan that produced several High Priests. The Gospel’s author, John, was not a member of the Twelve, but the son of Martha (Sukkah 52b). He closely matches the description given by Bishop Polycrates in his letter, a sacrificing priest who wore the petalon (i.e., emblem of the High Priest). This John "the Elder" was a follower of Jesus referred to by Papias, and an eyewitness to his ministry. He was the right age to have lived until the time of Trajan (according to Irenaeus). Baltz says John is probably the disciple ον ηγαπα ο Ιησους, and Eleazar is the disciple ον εφιλει ο Ιησους in the Gospel.

Mary Magdalene

Another school of thought has proposed that the Beloved Disciple in the Gospel of John really was originally Mary Magdalene. To make this claim and maintain consistency with scripture, the theory is suggested that Mary's separate existence in the two common scenes with the Beloved Disciple[Jn 19:25-27][20:1-11] were later modifications, hastily done to authorize the gospel in the late 2nd century. Both scenes are claimed to have inconsistencies both internally and in reference to the synoptic Gospels, possibly coming from rough editing to make Mary Magdalene and the Beloved Disciple appear as different persons.[5]

In the Gospel of Mary, part of the New Testament apocrypha — specifically the Gnostic gospels uncovered at Nag Hammadi — a certain Mary who is commonly identified as Mary Magdalene is constantly referred to as being loved by Jesus more than the others.[16] In the Gospel of Philip, another Gnostic Nag Hammadi text, the same is specifically said about Mary Magdalene.[17] For example, compare these passages from the Gospel of John and the apocryphal Gospel of Philip:

Gospel of Philip: There were three who always walked with the Lord: Mary his mother and her sister and Magdalene, the one who was called his companion. His sister and his mother and his companion were each a Mary.[18]

Gospel of John: 25Near the cross of Jesus stood his mother, his mother's sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. 26When Jesus saw his mother there, and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, "Dear woman, here is your son," 27and to the disciple, "Here is your mother." From that time on, this disciple took her into his home.[Jn 19:25-27]

Unknown priest or disciple

Brian J. Capper argues that the Beloved Disciple was a priestly member of a quasi-monastic, mystical and ascetic Jewish aristocracy, located on Jerusalem's prestigious southwest hill, who had hosted Jesus' last supper in that location,[19] citing the scholar D.E.H. Whiteley, who deduced that the Beloved Disciple was the host at the last supper.[20] Capper suggests, in order to explain the largely distinctive designation of the Beloved Disciple as one loved by Jesus, that the language of 'love' was particularly related to Jewish groups which revealed the distinctive social characteristics of 'virtuoso religion' in ascetic communities.[21] The British scholar Richard Bauckham[22] reaches the similar conclusion that the beloved disciple, who also authored the gospel attributed to John, was probably a literally sophisticated member of the (surprisingly extensive) high priestly family clan.

Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz suggest the testimony may have come from a lesser known disciple, perhaps from Jerusalem.[23]

Jesus' brother James

James D. Tabor[24] argues that the beloved disciple is Jesus' brother James. One of several pieces of evidence Tabor offers is a literal interpretation of John 19:26, "Then when Jesus saw His mother and the disciple whom He loved standing by, He said to His mother, Woman, behold your son." However, elsewhere in that gospel,[John 21:7] the beloved disciple refers to the risen Jesus as 'the Lord' rather than as 'my brother'.

Reasons for concealing the identity by name

Theories about the reference usually include an attempt to explain why this anonymizing idiom is used at all, rather than stating an identity.

Suggestions accounting for this are numerous. One common proposal is that the author concealed his name due simply to modesty. Another is that concealment served political or security reasons, made necessary by the threat of persecution or embarrassment during the time of the gospel's publication. The author may have been a highly placed person in Jerusalem who was hiding his affiliation with Christianity (see above reference to Richard Bauckham). Capper (see above reference) suggests that anonymity would have been appropriate for one living the withdrawn life of an ascetic, and that under the unnamed disciples of the Gospel may be present either the Beloved Disciple himself or others under his guidance who out of the humility of their ascetic commitment hid their identity or subsumed their witness under that of their spiritual master.

Martin L. Smith, a member of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, writes that the author of John's gospel may have deliberately obscured the identity of the Beloved Disciple in order that readers of the gospel may better identify with the disciple's relationship with Jesus:

Perhaps the disciple is never named, never individualized, so that we can more easily accept that he bears witness to an intimacy that is meant for each one of us. The closeness that he enjoyed is a sign of the closeness that is mine and yours because we are in Christ and Christ is in us."[25]

The idea of a beloved or special disciple is sometimes evoked in analysis of other texts from the New Testament Pseudepigrapha. In the Gospel of Thomas, Judas Thomas is the disciple taken aside by Jesus. In the Gospel of Judas, Judas Iscariot is favored with privy enlightening information and set apart from the other apostles. Another more recent interpretation draws from the Secret Gospel of Mark, existing only in fragments. In this interpretation, two scenes from Secret Mark and one at Mark 14:51-52 feature the same young man or youth who is unnamed but seems closely connected to Jesus. As the account in Secret Mark details a raising from the dead very similar to Jesus' raising of Lazarus in John 11:38-44, the young man is identified as Lazarus and associated with the Beloved Disciple.

Homoeroticism

Some scholars have suggested a homoerotic interpretation of Christ's relationship with the Beloved Disciple, although the majority of mainstream Biblical scholars argue against any scriptural evidence to this effect.[26][27] Tilborg suggests that the portrait in John is "positively attuned to the development of possibly homosexual behaviour". However, he cautions that "in the code... such imaginary homosexual behaviour is not an expression of homosexuality." Meanwhile Dunderberg has also explored the issue and argues that the absence of accepted Greek terms for "lover" and "beloved" discounts a purely erotic reading[28]

That the relationship was interpreted as a physical erotic relationship as early as the 16th century (albeit in a "heretical" context) which is documented, for example, in the trial for blasphemy of Christopher Marlowe, who was accused of claiming that "St. John the Evangelist was bedfellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom, that he used him as the sinners of Sodoma".[29] In accusing Marlowe of the "sinful nature" of homosexual acts, James I of England inevitably invited comparisons to his own erotic relationship with the Duke of Buckingham which he also compared to that of the Beloved Disciple.[30] Finally, Calcagno, a monk of Venice[31] faced trial and was executed in 1550 for claiming that "St. John was Christ's catamite".[27]

Dynes also makes a link to the modern day where in 1970s New York a popular religious group was established called the "Church of the Beloved Disciple", with the intention of giving a positive reading of the relationship to support respect for same-sex love.[27]

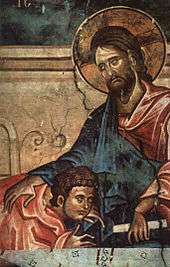

Art

In art, the Beloved Disciple is often portrayed as a beardless youth, usually as one of the Twelve Apostles at the Last Supper or with Mary at the crucifixion. In some medieval art, the Beloved Disciple is portrayed with his head in Christ's lap. Many artists have given different interpretations of John 13:25 which has the disciple whom Jesus loved "reclining next to Jesus" (v. 23; more literally, "on/at his breast/bosom," en to kolpo).[32]

Footnotes

- ↑ John 13:23, 19:26, 20:2, 21:7, 21:20

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History Book iii. Chapter xxiii.

- ↑ James D. G. Dunn and John William Rogerson, Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, p. 1210, ISBN 0-8028-3711-5.

- 1 2 Brown, Raymond E. 1970. "The Gospel According to John (xiii-xxi)". New York: Doubleday & Co. Pages 922, 955.

- ↑ Eusebius. Church History. Book V, Chapter 24:2

- ↑ Tractate 119 (John 19:24-30). Quote: "..the evangelist says, 'And from that hour the disciple took her unto his own,' speaking of himself. In this way, indeed, he usually refers to himself as the disciple whom Jesus loved: who certainly loved them all, but him beyond the others, and with a closer familiarity, so that He even made him lean upon His bosom at supper; in order, I believe, in this way to commend the more highly the divine excellence of this very gospel, which He was thereafter to preach through his instrumentality."

- ↑ Matthew 26:20 and Mark 14:17

- ↑ "'beloved disciple.'" Cross, F. L., ed. (2005) The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church; 3rd ed., revised by Elizabeth A. Livingstone. New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-280290-9

- ↑ Merrill F. Unger, The New Unger's Bible Dictionary, Chicago: Moody, 1988; p. 701

- ↑ as Hahn, Scott (2003). The Gospel of John: Ignatius Catholic Study Bible. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-89870-820-2.

- ↑ Morris, Leon (1995). The Gospel according to John. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8028-2504-9.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible (Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985) p. 355

- ↑ W.R.F. Browning, A Dictionary of the Bible, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 207.

- ↑ Baltz, Frederick. The Mystery of the Beloved Disciple: New Evidence, Complete Answer. Infinity Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-0741462053

- ↑ King, Karen L. Why All the Controversy? Mary in the Gospel of Mary. "Which Mary? The Marys of Early Christian Tradition" p. 74. F. Stanley Jones, ed. Brill, 2003

- ↑ See http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/gop.html

- ↑ NHC II.3.59.6-11 (Robinson 1988: 145)

- ↑ 'With the Oldest Monks...' Light from Essene History on the Career of the Beloved Disciple?, Journal of Theological Studies 49 (1998) pp. 1–55

- ↑ D.E.H. Whiteley, 'Was John written by a Sadducee?, Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II.25.3 (ed. H. Temporini and W. Haase, Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995), pp. 2481–2505, this quotation from p. 2494

- ↑ Brian J. Capper, ‘Jesus, Virtuoso Religion and Community of Goods.’ In Bruce Longenecker and Kelly Liebengood, eds., Engaging Economics: New Testament Scenarios and Early Christian Interpretation, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009, pp. 60–80.

- ↑ Bauckham, Richard. Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels As Eyewitness Testimony. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8028-3162-0

- ↑ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition). Chapter 2. Christian sources about Jesus.

- ↑ Tabor, James D. The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. Simon & Schuster (2006) ISBN 978-0-7432-8724-1

- ↑ Smith, Martin L., SSJE (1991). "Lying Close to the Breast of Jesus". A Season for the Spirit (Tenth anniversary ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cowley Publications. p. 190. ISBN 1-56101-026-X.

- ↑ Martti Nissinen, Kirsi Stjerna, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Ed. Wayne Dynes, Encyclopaedia of Homosexuality, New York, 1990, pp. 125-126.

- ↑ Stej Tilborg, Imaginative Love, 247-248 and p.109, 1993, Netherlands; Ismo Dunderberg, The Beloved Disciple in conflict?: Revisiting the Gospels of Thomas and John, Oxford University Press, 2006, p.176

- ↑ M. J. Trow, Taliesin Trow, Who Killed Kit Marlowe?: A Contract to Murder in Elizabethan England, London, 2002, p125

- ↑ King James and Letters of Homoerotic Desire. University Of Iowa Press, 1999.

- ↑ Scott Tucker, The queer question: essays on desire and democracy South End Press, 1999.

- ↑ Rodney A. Whitacre,"Jesus Predicts His Betrayal." IVP New Testament Commentaries, Intervarsity Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8308-1800-6

References

- Baltz, Frederick W. The Mystery of the Beloved Disciple: New Evidence, Complete Answer. Infinity Publishing, 2010. ISBN 0-7414-6205-2.

- Charlesworth, James H. The Beloved Disciple: Whose Witness Validates the Gospel of John?. Trinity Press, 1995. ISBN 1-56338-135-4.

- Smith, Edward R. The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved: Unveiling the Author of John's Gospel. Steiner Books/Anthroposophic Press, 2000. ISBN 0-88010-486-4.

|