Bell's palsy

| Bell's palsy | |

|---|---|

|

A person attempting to show his teeth and raise his eyebrows with Bell's palsy on his right side (left side of the image). | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | neurology |

| ICD-10 | G51.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 351.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 1303 |

| MedlinePlus | 000773 |

| eMedicine | emerg/56 |

| Patient UK | Bell's palsy |

| MeSH | D020330 |

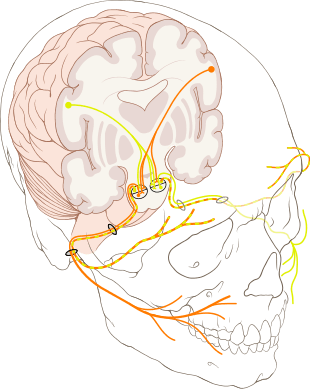

Bell's palsy is a form of facial paralysis resulting from a dysfunction of the cranial nerve VII (the facial nerve) causing an inability to control facial muscles on the affected side. Often the eye in the affected side cannot be closed. The eye must be protected from drying up, or the cornea may be permanently damaged, resulting in impaired vision. In some cases denture wearers experience some discomfort. The common presentation of this condition is a rapid onset of partial or complete paralysis that often occurs overnight. In rare cases (<1%), it can occur on both sides resulting in total facial paralysis.[1][2]

Bell's palsy is defined as a one-sided facial nerve paralysis of unknown cause. Several other conditions can also cause facial paralysis, e.g., brain tumor, stroke, myasthenia gravis, and Lyme disease; however, if no specific cause can be identified, the condition is known as Bell's palsy. It is thought that an inflammatory condition leads to swelling of the facial nerve. The nerve travels through the skull in a narrow bone canal beneath the ear. Nerve swelling and compression in the narrow bone canal are thought to lead to nerve inhibition or damage.

The condition normally gets better by itself with most achieving normal or near-normal function. Corticosteroids have been found to improve outcomes, when used early, while anti-viral medications are of questionable benefit.[3][4] Many show signs of improvement as early as 10 days after the onset, even without treatment.

Bell's palsy is the most common acute disease involving a single nerve and is the most common cause of acute facial nerve paralysis (>80%). It is named after Scottish anatomist and Edinburgh graduate Charles Bell (1774–1842), who first described it. It is more common in adults than children.

Signs and symptoms

Bell's palsy is characterized by a one-sided facial droop that comes on within 72 hours.[5]

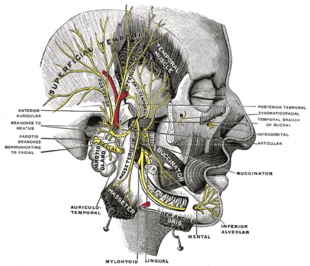

The facial nerve controls a number of functions, such as blinking and closing the eyes, smiling, frowning, lacrimation, salivation, flaring nostrils and raising eyebrows. It also carries taste sensations from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, via the chorda tympani nerve (a branch of the facial nerve). Because of this, people with Bell's palsy may present with loss of taste sensation in the anterior 2/3 of the tongue on the affected side.[6]

Although the facial nerve innervates the stapedial muscles of the middle ear (via the tympanic branch), sound sensitivity and dysacusis are hardly ever clinically evident.[6]

Although defined as a mononeuritis (involving only one nerve), people diagnosed with Bell’s palsy may have "myriad neurological symptoms" including "facial tingling, moderate or severe headache/neck pain, memory problems, balance problems, ipsilateral limb paresthesias, ipsilateral limb weakness, and a sense of clumsiness" that are "unexplained by facial nerve dysfunction".[7]

Cause

Some viruses are thought to establish a persistent (or latent) infection without symptoms, e.g., the varicella-zoster virus[8] and Epstein-Barr viruses, both of the herpes family. Reactivation of an existing (dormant) viral infection has been suggested[9] as a cause of acute Bell's palsy. Studies suggest that this new activation could be preceded by trauma, environmental factors, and metabolic or emotional disorders, thus suggesting that a host of different conditions may trigger reactivation.[10]

Familial inheritance has been found in 4–14% of cases.[11] Bell's palsy is three times more likely to occur in pregnant women than non-pregnant women.[12] It is also considered to be four times more likely to occur in diabetics than the general population.[13]

Differential diagnosis

Once the facial paralysis sets in, many people may mistake it as a symptom of a stroke; however, there are a few subtle differences. A stroke will usually cause a few additional symptoms, such as numbness or weakness in the arms and legs. And unlike Bell's palsy, a stroke will usually let patients control the upper part of their faces. A person with a stroke will usually have some wrinkling of their forehead.[14]

One disease that may be difficult to exclude in the differential diagnosis is involvement of the facial nerve in infections with the herpes zoster virus. The major differences in this condition are the presence of small blisters, or vesicles, on the external ear and hearing disturbances, but these findings may occasionally be lacking (zoster sine herpete). Reactivation of existing herpes zoster infection leading to facial paralysis in a Bell's palsy type pattern is known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome type 2.

Lyme disease may produce facial palsy.[15] Sometimes the facial palsy occurs at the same time as the classic erythema migrans rash.[15] Other times, it occurs later.[15] In areas where Lyme disease is common, it may be the cause of facial palsy in half of cases.[15]

Pathophysiology

Bell's palsy occurs due to a malfunction of the facial nerve (VII cranial nerve), which controls the muscles of the face. Facial palsy is typified by inability to control movement in the facial muscles. The paralysis is of the infranuclear/lower motor neuron type.

It is thought that as a result of inflammation of the facial nerve, pressure is produced on the nerve where it exits the skull within its bony canal, blocking the transmission of neural signals or damaging the nerve. Patients with facial palsy for which an underlying cause can be found are not considered to have Bell's palsy per se. Possible causes include tumor, meningitis, stroke, diabetes mellitus, head trauma and inflammatory diseases of the cranial nerves (sarcoidosis, brucellosis, etc.). In these conditions, the neurologic findings are rarely restricted to the facial nerve. Babies can be born with facial palsy.[16] In a few cases, bilateral facial palsy has been associated with acute HIV infection.

In some research the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) has been identified in a majority of cases diagnosed as Bell's palsy.[17] This has given hope for anti-inflammatory and anti-viral drug therapy (prednisone and acyclovir). Other research, however, identifies HSV-1 in only 31 cases (18 percent), herpes zoster (zoster sine herpete) in 45 cases (26 percent) in a total of 176 cases clinically diagnosed as Bell's Palsy.[9] That infection with herpes simplex virus should play a major role in cases diagnosed as Bell's palsy therefore remains a hypothesis that requires further research.

In addition, the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection is associated with demyelination of nerves. This nerve damage mechanism is different from the above-mentioned - that edema, swelling and compression of the nerve in the narrow bone canal is responsible for nerve damage. Demyelination may not even be directly caused by the virus, but by an unknown immune system response.

Diagnosis

Bell's palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning it is diagnosed by elimination of other reasonable possibilities. By definition, no specific cause can be determined. There are no routine lab or imaging tests required to make the diagnosis.[5] The degree of nerve damage can be assessed using the House-Brackmann score.

One study found that 45% of patients are not referred to a specialist, which suggests that Bell’s palsy is considered by physicians to be a straightforward diagnosis that is easy to manage.[7]

Other conditions that can cause similar symptoms include: herpes zoster, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, stroke, and brain tumors.[5]

Treatment

Steroids have been shown to be effective at improving recovery in Bell's palsy while antivirals have not.[5] In those who are unable to close their eyes, eye protective measures are required.[5]

Steroids

Corticosteroid such as prednisone significantly improves recovery at 6 months and are thus recommended.[18] Early treatment (within 3 days after the onset) is necessary for benefit[19] with a 14% greater probability of recovery.[20]

Antivirals

One review found that antivirals (such as aciclovir) are ineffective in improving recovery from Bell's palsy beyond steroids alone in mild to moderate disease.[21] Another review found a benefit but stated the evidence was not very good to support this.[22]

In severe disease it is also unclear. One 2015 review found no effect regardless of severity.[23] Another review found a small benefit when added to steroids in those with severe disease.[24]

They are commonly prescribed due to a theoretical link between Bell's palsy and the herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus.[3] There is still the possibility that they might result in a benefit less than 7% as this has not been ruled out.[25]

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy can be beneficial to some individuals with Bell’s palsy as it helps to maintain muscle tone of the affected facial muscles and stimulate the facial nerve.[26] It is important that muscle re-education exercises and soft tissue techniques be implemented prior to recovery in order to help prevent permanent contractures of the paralyzed facial muscles.[26] To reduce pain, heat can be applied to the affected side of the face.[27] There is no high quality evidence to support the role of electrical stimulation for Bell's palsy.[28]

Surgery

Surgery may be able to improve outcomes in facial nerve palsy that has not recovered.[29] A number of different techniques exist.[29] Smile surgery or smile reconstruction is a surgical procedure that may restore the smile for people with facial nerve paralysis. It is unknown if early surgery is beneficial or harmful.[30] Adverse effects include hearing loss which occurs in 3–15% of people.[31] As of 2007 the American Academy of Neurology did not recommend surgical decompression.[31]

Alternative medicine

The efficacy of acupuncture remains unknown because the available studies are of low quality (poor primary study design or inadequate reporting practices).[32] There is very tentative evidence for hyperbaric oxygen therapy in severe disease.[33]

Prognosis

Most people with Bell's palsy start to regain normal facial function within 3 weeks—even those who do not receive treatment.[34] In a 1982 study, when no treatment was available, of 1,011 patients, 85% showed first signs of recovery within 3 weeks after onset. For the other 15%, recovery occurred 3–6 months later. After a follow-up of at least 1 year or until restoration, complete recovery had occurred in more than two-thirds (71%) of all patients. Recovery was judged moderate in 12% and poor in only 4% of patients.[35] Another study found that incomplete palsies disappear entirely, nearly always in the course of one month. The patients who regain movement within the first two weeks nearly always remit entirely. When remission does not occur until the third week or later, a significantly greater part of the patients develop sequelae.[36] A third study found a better prognosis for young patients, aged below 10 years old, while the patients over 61 years old presented a worse prognosis.[10]

Major complications of the condition are chronic loss of taste (ageusia), chronic facial spasm, facial pain and corneal infections. To prevent the latter, the eyes may be protected by covers, or taped shut during sleep and for rest periods, and tear-like eye drops or eye ointments may be recommended, especially for cases with complete paralysis. Where the eye does not close completely, the blink reflex is also affected, and care must be taken to protect the eye from injury.

Another complication can occur in case of incomplete or erroneous regeneration of the damaged facial nerve. The nerve can be thought of as a bundle of smaller individual nerve connections that branch out to their proper destinations. During regrowth, nerves are generally able to track the original path to the right destination - but some nerves may sidetrack leading to a condition known as synkinesis. For instance, regrowth of nerves controlling muscles attached to the eye may sidetrack and also regrow connections reaching the muscles of the mouth. In this way, movement of one also affects the other. For example, when the person closes the eye, the corner of the mouth lifts involuntarily.

Around 9%[37] of patients have some sort of sequelae after Bell's palsy, typically the synkinesis already discussed, or spasm, contracture, tinnitus and/or hearing loss during facial movement or crocodile tear syndrome. This is also called gustatolacrimal reflex or Bogorad’s Syndrome and involves the sufferer shedding tears while eating. This is thought to be due to faulty regeneration of the facial nerve, a branch of which controls the lacrimal and salivary glands. Gustatorial sweating can also occur.

Epidemiology

The number of new cases of Bell's palsy is about 20 per 100,000 population per year.[38] The rate increases with age.[38] Bell’s palsy affects about 40,000 people in the United States every year. It affects approximately 1 person in 65 during a lifetime.

A range of annual incidence rates have been reported in the literature: 15,[11] 24,[39] and 25–53[7] (all rates per 100,000 population per year). Bell’s palsy is not a reportable disease, and there are no established registries for patients with this diagnosis, which complicates precise estimation.

History

The Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (865–925) detailed the first known description of peripheral and central facial palsy.[40][41]

Cornelis Stalpart van der Wiel (1620–1702) in 1683 gave an account of Bell’s palsy and credited Ibn Sina (980–1037) for describing this condition before him. James Douglas (1675–1742) and Nicolaus Anton Friedreich (1761–1836) also described it.

Sir Charles Bell, for whom the condition is named, presented three cases at the Royal Society of London in 1829. Two cases were idiopathic and the third was due to a tumour of the parotid gland.

References

- ↑ Price, Fife, T; Fife, DG (January 2002). "Bilateral simultaneous facial nerve palsy". J Laryngol Otol. 116 (1): 46–8. doi:10.1258/0022215021910113. PMID 11860653.

- ↑ Jain V, Deshmukh A, Gollomp S (July 2006). "Bilateral facial paralysis: case presentation and discussion of differential diagnosis". J Gen Intern Med 21 (7): C7–10. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00466.x. PMC 1924702. PMID 16808763.

- 1 2 Sullivan FM; Swan IR; Donnan PT; et al. (October 2007). "Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell's palsy". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (16): 1598–607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072006. PMID 17942873.

- ↑ Gagyor, I; Madhok, VB; Daly, F; Somasundara, D; Sullivan, M; Gammie, F; Sullivan, F (4 May 2015). "Antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis).". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 5: CD001869. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001869.pub5. PMID 25938618.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baugh, RF; Basura, GJ; Ishii, LE; Schwartz, SR; Drumheller, CM; Burkholder, R; Deckard, NA; Dawson, C; Driscoll, C; Gillespie, MB; Gurgel, RK; Halperin, J; Khalid, AN; Kumar, KA; Micco, A; Munsell, D; Rosenbaum, S; Vaughan, W (November 2013). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell's Palsy Executive Summary.". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 149 (5): 656–63. doi:10.1177/0194599813506835. PMID 24190889.

- 1 2 Mumenthaler, Mark; Mattle, Heinrich (2006). Fundamentals of Neurology. Germany: Thieme. p. 197. ISBN 3131364513.

- 1 2 3 Morris AM; Deeks SL; Hill MD; et al. (2002). "Annualized incidence and spectrum of illness from an outbreak investigation of Bell's palsy". Neuroepidemiology 21 (5): 255–61. doi:10.1159/000065645. PMID 12207155.

- ↑ Facial Nerve Problems and Bell's Palsy Information on MedicineNet.com

- 1 2 Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Chida E, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y (2001). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation and antiviral therapy in patients with acute peripheral facial palsy". Auris Nasus Larynx 28 (Suppl): S13–7. doi:10.1016/S0385-8146(00)00105-X. PMID 11683332.

- 1 2 Kasse C.A, Ferri R.G, Vietler E.Y.C, Leonhardt F.D, Testa J.R.G, Cruz O.L.M (October 2003). "Clinical data and prognosis in 1521 cases of Bell's palsy". International Congress Series 1240: 641–7. doi:10.1016/S0531-5131(03)00757-X.

- 1 2 Döner F, Kutluhan S; Kutluhan (2000). "Familial idiopathic facial palsy". Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 257 (3): 117–9. doi:10.1007/s004050050205. PMID 10839481.

- ↑ Bender, Paula Gillingham. "Facing Bell's Palsy while pregnant." (Commercial website). Sheknows: Pregnancy and Baby. Retrieved on 2007-09-06.

- ↑ "Bell's Palsy InfoSite & Forums: Facial Paralysis FAQs" (Website). Bell's Palsy Information Site. Retrieved on 2007-09-06.

- ↑ S.C. TV Reporter Loses Her Smile after a Bell's Palsy Attack

- 1 2 3 4 Lorch, M; Teach, SJ (Oct 2010). "Facial nerve palsy: etiology and approach to diagnosis and treatment.". Pediatric emergency care 26 (10): 763–9; quiz 770–3. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181f3bd4a. PMID 20930602.

- ↑ - MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Facial nerve palsy due to birth trauma retrieved 10 September 2008

- ↑ Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, Doi T, Hato N, Yanagihara N (1996). "Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle". Annals of Internal Medicine 124 (1 Pt 1): 27–30. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_Part_1-199601010-00005. PMID 7503474.

- ↑ Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Daly F, Ferreira J (2010). Salinas, Rodrigo A, ed. "Corticosteroids for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3 (3): CD001942. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001942.pub4. PMID 20238317.

- ↑ Hazin, R; Azizzadeh, B; Bhatti, MT (November 2009). "Medical and surgical management of facial nerve palsy". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 20 (6): 440–50. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283313cbf. PMID 19696671.

- ↑ Gronseth, GS; Paduga, R (Nov 7, 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: Steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology 79 (22): 2209–13. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318275978c. PMID 23136264.

- ↑ Turgeon, RD; Wilby, KJ; Ensom, MH (June 2015). "Antiviral Treatment of Bell's Palsy Based on Baseline Severity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.". The American Journal of Medicine 128 (6): 617–28. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.033. PMID 25554380.

- ↑ Gagyor, I; Madhok, VB; Daly, F; Somasundara, D; Sullivan, M; Gammie, F; Sullivan, F (9 November 2015). "Antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis).". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 11: CD001869. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001869.pub8. PMID 26559436.

- ↑ Turgeon, Ricky D.; Wilby, Kyle J.; Ensom, Mary H.H. (June 2015). "Antiviral Treatment of Bell's Palsy Based on Baseline Severity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Medicine 128 (6): 617–628. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.033. PMID 25554380.

- ↑ Gagyor, I; Madhok, VB; Daly, F; Somasundara, D; Sullivan, M; Gammie, F; Sullivan, F (1 July 2015). "Antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis).". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 7: CD001869. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001869.pub6. PMID 26130372.

- ↑ Gronseth, GS; Paduga, R; American Academy of Neurology (Nov 27, 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology 79 (22): 2209–13. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318275978c. PMID 23136264.

- 1 2 "Bell's Palsy Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. April 2003. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Shafshak, TS (March 2006). "The treatment of facial palsy from the point of view of physical and rehabilitation medicine". Europa Medicophysica 42 (1): 41–7. PMID 16565685.

- ↑ Teixeira, Lázaro J; Valbuza, J. S.; Prado, G. F. (Dec 2011). "Physical therapy for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006283. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006283.pub3. PMID 22161401.

- 1 2 Hazin R, Azizzadeh B, Bhatti MT; Azizzadeh; Bhatti (November 2009). "Medical and surgical management of facial nerve palsy". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 20 (6): 440–50. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283313cbf. PMID 19696671.

- ↑ McAllister, K; Walker, D; Donnan, PT; Swan, I (Feb 16, 2011). Swan, Iain, ed. "Surgical interventions for the early management of Bell's palsy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007468. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007468.pub2. PMID 21328293.

- 1 2 Tiemstra, JD; Khatkhate, N (Oct 1, 2007). "Bell's palsy: diagnosis and management". American family physician 76 (7): 997–1002. PMID 17956069.

- ↑ Chen, N; Zhou, M; He, L; Zhou, D; Li, N (4 August 2010). "Acupuncture for Bell's palsy.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (8): CD002914. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002914.pub5. PMID 20687071.

- ↑ Holland, NJ; Bernstein, JM; Hamilton, JW (15 February 2012). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for Bell's palsy.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2: CD007288. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007288.pub2. PMID 22336830.

- ↑ Karnath, B. "Bell Palsy: Updated Guideline for Treatment". Consultant. HMP Communications. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ↑ Peitersen E (1982). "The natural history of Bell's palsy". Am J Otol 4 (2): 107–11. PMID 7148998. quoted in Roob G, Fazekas F, Hartung HP; Fazekas; Hartung (1999). "Peripheral facial palsy: etiology, diagnosis and treatment". Eur. Neurol. 41 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1159/000007990. PMID 9885321.

- ↑ Peitersen E, Andersen P; Andersen (1966). "Spontaneous course of 220 peripheral non-traumatic facial palsies". Acta Otolaryngol.: Suppl 224:296+. PMID 6011525.

- ↑ Yamamoto E, Nishimura H, Hirono Y; Nishimura; Hirono (1988). "Occurrence of sequelae in Bell's palsy". Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 446: 93–6. PMID 3166596.

- 1 2 Ahmed A (2005). "When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment". Cleve Clin J Med 72 (5): 398–401, 405. doi:10.3949/ccjm.72.5.398. PMID 15929453.

- ↑ Wolf SR (1998). "[Idiopathic facial paralysis]". HNO (in German) 46 (9): 786–98. doi:10.1007/s001060050314. PMID 9816532.

- ↑ Sajadi MM, Sajadi MR, Tabatabaie SM; Sajadi; Tabatabaie (July 2011). "The history of facial palsy and spasm: Hippocrates to Razi". Neurology 77 (2): 174–8. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182242d23. PMC 3140075. PMID 21747074.

- ↑ van de Graaf RC, Nicolai JP; Nicolai (November 2005). "Bell's palsy before Bell: Cornelis Stalpart van der Wiel's observation of Bell's palsy in 1683". Otol. Neurotol. 26 (6): 1235–8. doi:10.1097/01.mao.0000194892.33721.f0. PMID 16272948.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bell's palsy. |

- Bell's palsy at DMOZ