Beaver Valley, Delaware and Pennsylvania

.jpg)

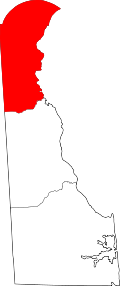

Beaver Valley (formerly known as Chandler’s Hollow) straddles the Pennsylvania and Delaware border in Delaware County, PA and New Castle County, DE. An unincorporated place name, it is traversed by several streams which drain to Beaver Run which itself empties into the Brandywine River. It is approximately bounded by US Route 202 to the east, The Brandywine River to the west, Thompsons Bridge Road to the south, and Smithbridge Road to the north, with Beaver Valley Road encircling a large portion of the valley. The majority of the lands in Beaver Valley have been owned for decades by The Woodlawn Trustees, which designated in the early 1970s all of its Brandywine Hundred and Delaware County holdings in Beaver Valley and elsewhere as a Wildlife Refuge. In 2012, The Woodlawn Trustees submitted development plans to Concord Township Supervisors in Delaware County for the purpose of constructing approximately 500 housing units and a 225,000 square foot national retail store, all of which would adjoin the First State National Historical Park in Chadds Ford Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania and New Castle County, Delaware. The original plans were withdrawn, but the developers – Frank McKee and the Julian brothers, Richard and Frank – came back with new plans entitled "Vineyard Commons" which called for 171 houses spread across approximately 150 acres.

Geography

Roughly half of Beaver Valley lies in southeastern Pennsylvania in Concord and Chadds Ford Townships, in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. The other half is situated in northern Delaware in The Brandywine Hundred in New Castle County. The historic Brandywine River runs along Beaver Valley’s western border and one of Pennsylvania and Delaware’s most heavily traveled roads, Route 202, forms its eastern border. Much of Beaver Valley falls within the First State National Monument declared by President Obama in March 2013 (later redesignated the First State National Historical Park) and which represents Delaware County’s and the state of Delaware’s only representation in the National Park Service.

Across the Brandywine to the west sits the thousand acre Granogue, a du Pont estate occupied as of January, 2014 by Irenee du Pont. Other former du Pont lands became Brandywine Creek State Park, which adjoins Beaver Valley in the south. The only cave known to exist in the state of Delaware lies 200 feet west of the intersection of Beaver Valley and Beaver Dam Roads in the heart of the valley. Featuring The Brandywine Valley and Beaver Valley in their April print and online editions, National Geographic magazine highlighted the historic importance of this area.[1] John Thomas Scharf, an early chronicler of the area, described Beaver Valley as

“...a hamlet on Beaver Run where that stream crosses the Pennsylvania line. The place is also locally known as Chandler’s Hollow, being situated in a deep vale, through which flows the run to mingle its waters with those of the Brandywine, a short distance below. Amor Chandler had the first store at Beaver Valley In 1835 Charles and Martin Palmer were in trade. Lewis Talley followed later and with some partners manufactured shoes in connection with the store. John Chandler was also in trade, and since 1876, A. H. Chandler has been a merchant here These merchants have also been postmasters of the Beaver Valley office The hamlet has about a dozen and shops." [2]

Geology

Beaver Valley falls within the Piedmont plateau, a region located between the Atlantic Coastal Plain and the Appalachian Mountains. The Piedmont of Pennsylvania is divided into three distinct sections: the Piedmont Uplands, the Piedmont Lowlands, and the Gettysburg-Newark Lowlands. Beaver Valley is located on the upland section of the Piedmont wherein the oldest exposed rocks in Pennsylvania can be found.[3] These rocks have a complex history and a vast array of different minerals. Much of the rock was altered (squeeze and/or melted) during the formation of Rodinia during the Grenville orogeny.[3] One result of this metamorphism was the creation of significant deposits of mica which can be found in the National Historical Park near the intersection of Ramsey Road and Thompsons Bridge Road. In fact, mica was quarried there by early settlers, partly for use in early windows.These rocks eventually provided the platform or base for the later deposition of eroded sediment that consolidated into main bedrock referred to as the Wissahickon Formation, the particular variety of which in Beaver Valley is called the Mt. Cuba Wissahickon Formation. Characterized by assorted metamorphic and sedimentary rock types, Beaver Valley’s bedrock provides the parent material for soils which include of a mix of gneiss and schist with subordinate amphibolite and pegmatite.[3] Erosion and chemical weathering of the Wissahickon bedrock give regional soils particular chemical characteristics that support diversified farming. Most upland Piedmont soils are fertile,[3] and Beaver Valley is no exception with local farmers planting a variety of crops on lands leased to them by The Woodlawn Trustees.

Delaware's only cave

Up until the mid-twentieth century and despite ample historical evidence that Delaware Indians used it for shelter, the National Speleological Society maintained that Delaware was the only state in the union lacking a cave.[4] In 1958, a local resident, George Jackson, added this cave to the national cave files.[5] The cave was the focus of research in the 1940s when the Archeological Society of Delaware conducted a dig which revealed conclusively that Indians had used it for shelter and storage.[4] Sitting just 100 feet from the Pennsylvania border this small cave extends just 56 feet to its furthest reach, but has become one of the most researched caves in the United States relative to its size. Jack Speece notes that the cave has gone by many names in its history. Indian Cave, Beaver Valley Rock Shelter, and Wolf Rock Cave preceded the now more commonly accepted "Beaver Valley Cave."[4]

Ecology

Abutting intensive development on its northerly and easterly borders, Beaver Valley’s forests are reminiscent of an earlier age, and while they are in the process of slowly healing from 200 years of agricultural and milling operations, they are beginning to resemble again what the Lenni Lenape had known. Primarily deciduous forests consisting of native tulip poplar, sycamore, beech, red and white oak, cherry, ash, walnut, American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), and one documented American Chestnut, Beaver Valley’s woods are among the most extensive and mature in southeastern Pennsylvania.[3] Several patches offer “interior forest” conditions, critical nesting habitat for several neotropical migrant songbird species. Many of these tracts lie at least one hundred meters from any canopy fragmenting feature like roads, power lines, or fields and offer hundreds of migratory and sedentary bird species some of the last remaining unspoiled habitat in Southeastern Pennsylvania, increasingly found in short supply and degraded quality.[3]

Beaver Valley is a critical part of the Brandywine and Delaware River watersheds. At least one of its streams remains cold enough and pure enough to hold a small population of native brook trout, at the extreme southern edge of their range.[3] The once teeming population of minnows, salamanders, and crawfish supported a feral population of mink (gone wild from a failed ranching experiment), native populations of weasels, and substantial populations of skunk and raccoons. Continued efforts to improve the quality of Beaver Run have made the return of its eponymous mammal more likely. A significant number of old fields are very early in the long process of reverting from past agricultural uses to meadow although several large fields in Beaver Valley are still leased to local farmers for hay production. The forest was likely selectively cut for fuel wood and timber several times since colonial times, however much of the existing forests have been standing for well over 100 years. Some of the trees were likely considered less desirable for lumber and fuel or were less accessible due to steep slopes. While the Beaver Valley Woods is not considered virgin forest, some individual trees may be 200–300 years old or older.[3]

History

Before the Beaver Valley was settled by Europeans, it was traversed by Lenni Lenape, traveling from their summer camp at the “Big Bend” of the Brandywine River to Naaman’s Creek – pausing at Beaver Valley Cave to seek rest and shelter, to store produce and supplies. According to a local historian, “in the late 17th and 18th centuries, Beaver Valley’s lands were taken up by Europeans, many Quaker, many coming with William Penn in pursuit of their personal peaceable kingdoms. The lands were cleared, surveyed, and domesticated into the dispersed family farms that characterized settlement patterns in the region. These farms were “mixed” – producing a variety of products (especially grain) for home use, and export to Colonial America’s largest city, Philadelphia, and from there to Europe and the West Indies. Conestoga Wagons rumbled by on the “great road” (today, 202), en route to mills and ports, including those in the new town of Wilmington, stopping for rest and refreshment at the taverns that stood at each intersection of Beaver Valley and the Great Road – The Nine Ton in Pennsylvania and another in Delaware.”[6]

A stray reference to Beaver Valley in 1694 refers to the lands bordering Beaver Run as “mill lands,” and surveyors laying out Beaver Valley Road in 1712 passed by “the mill that Chandler is building.” Until well into the 19th century, Beaver Run and its tributaries supported small mills – generally managed by their owners and from one to three workers that produced a range of products, from lumber, to tin, to flax, to paper. By the third quarter of the 19th century the Valley had become a thriving community of several hundred people organized around two schools, the mills, and the characteristic family farms of 40 to 120 acres.[7][8] Many of the mills and dams in Beaver Valley were damaged or destroyed as the result of the flood of 1843.[9][10]

The landscape of Beaver Valley in the Woodlawn Wildlife Refuge has more than a trace of these early European beginnings, some dating back to 1683. Stone and wood-framed 18th and 19th century dwellings and outbuildings – barns, corn cribs, cart sheds, and springhouses - dot the landscape, a unique manifestation of the regional rural heritage. Located less than 2 miles from the famous Brandywine Battlefield, the Delaware County Planning Commission has noted that the area has "high potential" for archaeological resources given that it has remained undeveloped since the Township's founding before 1683.[3]

Regional and national recognition

The importance of these lands has been recognized by New Castle and Delaware Counties.[3][11] New Castle County has recommended that the Delaware roadways that wind through Beaver Valley be designated National Scenic Highways while The Delaware County Planning Commission has encouraged the preservation and protection of the lands in the valley.[3] The United States federal government has weighed in, too, designating 1,100 acres in New Castle County and Chadds Ford, Delaware County as First State Historical Park, of which Beaver Valley constitutes a large part.[1][12] The majestic character of the valley was effectively captured by the National Geographic in April 2013 when it described it as existing “at some indeterminate point in time…somewhere between the 18th and the 20th centuries.”[1] Beaver Valley looks much like it did when George Washington's Continental Army camped nearby, and an old legend in the valley tells of British troops commandeering supplies from locals during their march across the Brandywine Valley. According to local family history, The Redcoats made off with Robert Green’s best mare, as he continued to plow.

Brandywine Summit Camp Meeting

A part of Beaver Valley’s history lives on in The Brandywine Summit Camp Meeting on Beaver Valley Road. Established barely one year after the end of the Civil War in 1866, it is one of the oldest continually operating camp meetings in Pennsylvania, becoming a summertime destination of middle class Methodists from Wilmington, DE to West Chester, PA in the late nineteenth century and throughout much of the twentieth.[13]

“It is a prime example of the American Methodist Camp Meeting Movement, a movement made popular in the decades following the Civil War. Its layout and architecture, featuring gabled cottages along avenues surrounding a central square containing a tabernacle, typifies the general design of camp meetings at that time. The wooded landscape of the camp was once part of the William Johnson farm, and the specific thirteen acres which comprise the district was once known as Johnson’s Woods. The Johnson farmhouse still stands on Route 202, substantially renovated, and houses the Brandywine Conference and Visitors Bureau.”[13]

Recreational uses

Crisscrossing upland meadows and pristine streams, heavily wooded areas or lush valleys, Beaver Valley's extensive network of packed-earth paths offers a wide variety of terrain for a wide variety of recreational activities.[14] Bikers, hikers, horseback riders, runners, birders, artists, cross country skiers,

and dog walkers can frequently be seen taking advantage of what Beaver Valley offers.[15] A half dozen horse farms exist throughout the valley and horseback riders make good use of the farms’ proximity to the trails. On any given day, several mountain bike clubs in the area will ride en masse in colorful array.[16] Birders frequent the valley, also, to take in the hundreds of migratory and sedentary bird species stopping or living in Beaver Valley. A calm summer evening will draw artists to the fields at the eastside of the valley, and their paintings ornament the walls of many a restaurant and business in the Brandywine Valley. A number of hiking clubs and recreational meetup groups schedule hikes in the valley on a regular basis in every season.[17] A short loop through a part of the valley might take a dog walker a half hour while more serious hikers can wander for several hours through The Woodlawn Wildlife Refuge, Brandywine State Park, The First State National Historical Park, and beyond. On a summer ride or hike down to the river, one might witness a flotilla of kayakers or rafters drifting down to Thompson’s Bridge [18][19][20] or a pace line of cyclists racing along Brandywine Creek Drive. Several cycling and hiking groups help maintain the trails in the wildlife refuge and can frequently be seen with chainsaws clearing fallen trees.[21]

Woodlawn Wildlife Refuge Controversy

In the early 20th century, William Poole Bancroft, a wealthy Wilmington philanthropist, saw the city spreading beyond its borders and recognized the urgent need to protect the lands around Wilmington for future generations to enjoy. To that end, he created a corporation called “The Woodlawn Trustees” and charged it with fulfilling his vision of securing parkland for a future Wilmington.[22] Accordingly, throughout the first half of the 20th century, Woodlawn purchased thousands of acres of land north of Wilmington in The Brandywine Hundred and in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. From the 20s until the 60s, Woodlawn also developed more than a half dozen high income communities closer to Wilmington, DE, some of which include Alapocas, Edenridge, Woodbrook, and Tavistock. At some point in the late 60s or early 70s, The Woodlawn Trustees designated their remaining land holdings in and around Beaver Valley and The Brandywine Hundred as a wildlife refuge, installing hundreds of “Wildlife Refuge” signs at considerable expense around the perimeter of their lands.[23] In 2012, Woodlawn sold 1,100 acres of its wildlife refuge to The Mount Cuba Foundation for approximately 21 million dollars.[24] The 1,100 acres were turned over to The National Park Service by The Mount Cuba Foundation via The Conservation Fund, and in March, 2013, the Obama administration declared these lands as The First State National Monument.[25][26] Six months prior to these events, Woodlawn announced plans in mid 2012 to build approximately 500 homes and a 225,000 square foot retail "big box" store in Beaver Valley on 324 of the remaining 775 acres of the Woodlawn Wildlife Refuge on lands directly adjoining what would shortly become The First State National Monument, sparking widespread community opposition.[26]

The original plans were withdrawn, but the developers – Frank McKee and the Julian brothers, Richard and Frank – came back with new plans entitled "Vineyard Commons" which called for 171 houses spread across approximately 230 acres. The Concord Board of Supervisors approved the preliminary version of these plans in spite of widespread public opposition and a large quantity of evidence presented by The Beaver Valley Conservancy that the plans did not conform to Concord Township zoning, SALDO, and Stormwater codes. In late March of 2015, The Beaver Valley Conservancy filed suit in Common Pleas Court in Media, Pennsylvania disputing the decision of the Concord Board of Supervisors on the grounds that they acted in bad faith, among other allegations. [27] The remaining ~100 acres of the originally disputed land is now equitably owned by Steven Wolfson who has indicated he intends to build residential housing.

Merlin Brubaker

Merlin Brubaker, a DuPont chemist, lived in Beaver Valley on a 51 acre estate for more than 40 years from the late 30s to the mid 80s. Wanting to conserve his 51 acres in Beaver Valley, and having turned down more generous offers to develop his land, Mr. Brubaker approached Stephen Clark, president of Woodlawn, in the late 70s and asked if they would purchase his estate and protect it from development. Woodlawn agreed and allowed Mr. Brubaker to continue to live on his old estate for as long as he wanted.[28] In June 2014, Frank McKee builders and The Julian Brothers' Eastern States Construction announced that Dr. Brubaker's former estate would become the central part of a 171 house development—which several groups are opposing. Some of the groups that would like to see Beaver Valley remain a natural place include The Beaver Valley Preservation Alliance, Save The Valley and The Beaver Valley Conservancy.

References

- 1 2 3 "Delaware National Park, at Last". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. 2013-04-25. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ Scharf, John Thomas (1888). History of Delaware: 1609 to 1888. Philadelphia: L. J. Richards and Co. p. 906.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "The Delaware County Natural Resources Inventory" (PDF). Naturalheritage.state.pa. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- 1 2 3 Speece, Jack. H. "The Cave of Delaware." History Session: Proceedings of the National Speleological Society Convention, Alpena, Michigan, August 4, 1977.

- ↑ Jackson, George F., "Caves in Delaware", NSS News, Vol. 16, No. 10, p. 99 Oct. 1958

- ↑ Michel, Jack. In a manner and fashion suitable to their degree”: A Preliminary Investigation of Material Culture in Early Rural Pennsylvania. Working Papers From the Regional Economic History Research Center volume 5, no. 1. Wilmington, DE: Eleutherian Mills, Hagley Foundation, 1981.

- ↑ Michel, Jack. "In a manner and fashion suitable to their degree”: A Preliminary Investigation of Material Culture in Early Rural Pennsylvania. Working Papers From the Regional Economic History Research Center volume 5, no. 1. Wilmington, DE: Eleutherian Mills, Hagley Foundation, 1981.

- ↑ Michel, Jack et al. A Place in Time: Continuity and Change in Mid-Nineteenth Century Delaware. Newark, DE: Center for Historic Architecture and Engineering, 1985.

- ↑ Ashmead, Henry Graham. History of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1884. 318-319. Print.

- ↑ "Flood of 1843 in Delaware County". Philly H2O. 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Brandy Wine Valley" (PDF). Delawaregreenways.org. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "Meehan, Casey, Toomey Call for Recognition of Delco's Woodlawn Trustees Property by National Park Service" (PDF). Savebeavervalley.org. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- 1 2 "BSCM Base". Bscmai.org. 2013-04-02. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Township of Concord". Township of Concord. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Residents Fighting Development In Delco Get Small Victory - Philadelphia News, Weather and Sports from WTXF FOX 29". Myfoxphilly.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Woodlawn Trustees Trails | Park Trail Maps | Mountain Biking | Hiking". GpsTrailSource. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Hike The Big One: Brandywine Creek, Woodlawn and 3 Estates: 20 Miles - Harry's Happy Hikers (Phoenixville, PA)". Meetup. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Troop 56 Brandywine River Tubing 2012". YouTube. 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Brandywine Creek drifting and fishing Part 03". YouTube. 2012-12-03. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Brandywine Creek, Chadds Ford, PA USA Meditation Life". YouTube. 2012-12-03. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Current & Future Trail Projects | Delaware Trail Spinners". Trailspinners.org. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "William Poole Bancroft". Woodlawntrustees.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "WoodlawnTrailSystem.pdf - Google Drive". Drive.google.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "A New National Park In Delaware". The Conservation Fund. 2013-03-25. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Kudos to conservation of Woodlawn property | The News Journal". delawareonline.com. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- 1 2 "DevelopmentMap-Parks.png - Google Drive". Drive.google.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Three Concord residents appeal Vineyard Commons approval". Delcotimes.com. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ↑ "brubaker letter.png - Google Drive". Docs.google.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 39°50′21″N 75°33′51″W / 39.83917°N 75.56417°W