Bayesian hierarchical modeling

Bayesian hierarchical modeling is a statistical model written in multiple levels (hierarchical form) that estimates the parameters of the posterior distribution using the Bayesian method.[1] The sub-models combine to form the hierarchical model, and the Bayes’ theorem is used to integrate them with the observed data, and account for all the uncertainty that is present. The result of this integration is the posterior distribution, also known as the updated probability estimate, as additional evidence on the prior distribution is acquired.

Frequentist statistics, the more popular foundation of statistics, has been known to contradict Bayesian statistics due to its treatment of the parameters as a random variable, and its use of subjective information in establishing assumptions on these parameters.[2] However, Bayesians argue that relevant information regarding decision making and updating beliefs cannot be ignored and that hierarchical modeling has the potential to overrule classical methods in applications where respondents give multiple observational data. Moreover, the model has proven to be robust, with the posterior distribution less sensitive to the more flexible hierarchical priors.

Hierarchical modeling is used when information is available on several different levels of observational units. The hierarchical form of analysis and organization helps in the understanding of multiparameter problems and also plays an important role in developing computational strategies.[3]

Philosophy

Numerous statistical applications involve multiple parameters that can be regarded as related or connected in such a way that the problem implies dependence of the joint probability model for these parameters.[4] Individual degrees of belief, expressed in the form of probabilities, come with uncertainty.[5] Amidst this is the change of the degrees of belief over time. As was stated by Professor José M. Bernardo and Professor Adrian F. Smith, “The actuality of the learning process consists in the evolution of individual and subjective beliefs about the reality.” These subjective probabilities are more directly involved in the mind rather than the physical probabilities.[6] Hence, it is with this need of updating beliefs that Bayesians have formulated an alternative statistical model which takes into account the prior occurrence of a particular event.[7]

Bayes’ theorem

The assumed occurrence of a real-world event will typically modify preferences between certain options. This is done by modifying the degrees of belief attached, by an individual, to the events defining the options.[8]

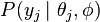

Suppose in a study of the effectiveness of cardiac treatments, with the patients in hospital j having survival probability  , the survival probability will be updated with the occurrence of y, the event in which a hypothetical controversial serum is created which, as believed by some, increases survival in cardiac patients.

, the survival probability will be updated with the occurrence of y, the event in which a hypothetical controversial serum is created which, as believed by some, increases survival in cardiac patients.

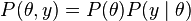

In order to make updated probability statements about  , given the occurrence of event y, we must begin with a model providing a joint probability distribution for

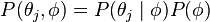

, given the occurrence of event y, we must begin with a model providing a joint probability distribution for  and y. This can be written as a product of the two distributions that are often referred to as the prior distribution

and y. This can be written as a product of the two distributions that are often referred to as the prior distribution  and the sampling distribution

and the sampling distribution  respectively:

respectively:

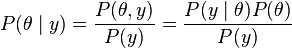

Using the basic property of conditional probability, the posterior distribution will yield:

This equation, showing the relationship between the conditional probability and the individual events, is known as Bayes’ Theorem. This simple expression encapsulates the technical core of Bayesian inference which aims to incorporate the updated belief,  , in appropriate and solvable ways.[8]

, in appropriate and solvable ways.[8]

Exchangeability

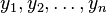

The usual starting point of a statistical analysis is the assumption that the n values  are exchangeable. If no information – other than data y – is available to distinguish any of the

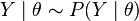

are exchangeable. If no information – other than data y – is available to distinguish any of the  ’s from any others, and no ordering or grouping of the parameters can be made, one must assume symmetry among the parameters in their prior distribution.[9] This symmetry is represented probabilistically by exchangeability. Generally, it is useful and appropriate to model data from an exchangeable distribution, as independently and identically distributed, given some unknown parameter vector

’s from any others, and no ordering or grouping of the parameters can be made, one must assume symmetry among the parameters in their prior distribution.[9] This symmetry is represented probabilistically by exchangeability. Generally, it is useful and appropriate to model data from an exchangeable distribution, as independently and identically distributed, given some unknown parameter vector  , with distribution

, with distribution  .

.

Finite exchangeability

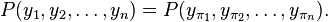

For a fixed number n, the set  is exchangeable if the joint probability

is exchangeable if the joint probability  is invariant under permutations of the indices. That is, for every permutation

is invariant under permutations of the indices. That is, for every permutation  or

or  of (1, 2, …, n),

of (1, 2, …, n),  [10]

[10]

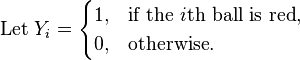

To visualize this is an exchangeable but not independent and identical (iid) example:

Consider an urn with one red ball and one blue ball with probability  of drawing either. Balls are drawn without replacement, i.e. after one ball is drawn from the n balls, there will be n − 1 remaining balls left for the next draw.

of drawing either. Balls are drawn without replacement, i.e. after one ball is drawn from the n balls, there will be n − 1 remaining balls left for the next draw.

Since the probability of selecting a red ball in the first draw and a blue ball in the second draw is equal to the probability of selecting a blue ball on the first draw and a red on the second draw, both of which are equal to 1/2 (i.e. ![[P(y_1 = 1, y_2 =0) = P(y_1=0,y_2=1)= \frac{1}{2}]](../I/m/6813b69d5bf77b7ab5823a09b986436a.png) ), then

), then  and

and  are exchangeable.

are exchangeable.

But the probability of selecting a red ball on the second draw given that the red ball has already been selected in the first draw is 0, and is not equal to the probability that the red ball is selected in the second draw which is equal to 1/2 (i.e. ![[P(y_2=1\mid y_1=1)=0 \ne P(y_2=1)= \frac{1}{2}]](../I/m/202af4a497736a000f1cdba657a3fc44.png) ). Thus,

). Thus,  and

and  are not independent.

are not independent.

If  are independent and identically distributed, then they are exchangeable, but not conversely true.[11]

are independent and identically distributed, then they are exchangeable, but not conversely true.[11]

Infinite exchangeability

An infinite exchangeability implies that every finite subset of an infinite sequence  ,

,  is exchangeable. That is, for any n, the sequence

is exchangeable. That is, for any n, the sequence  is exchangeable.[11]

is exchangeable.[11]

Hierarchical models

Components

Bayesian hierarchical modeling makes use of two important concepts in deriving the posterior distribution,[1] namely:

1. Hyperparameter: parameter of the prior distribution

2. Hyperprior: distribution of a parameter of the prior distribution

Say a random variable Y follows a normal distribution with parameters θ as the mean and 1 as the variance, that is  . The parameter

. The parameter  has a prior distribution given by a normal distribution with mean

has a prior distribution given by a normal distribution with mean  and variance 1, i.e.

and variance 1, i.e.  . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  follows another distribution given, for example, by the standard normal distribution,

follows another distribution given, for example, by the standard normal distribution,  . The parameter

. The parameter  is called the hyperparameter, while its distribution given by N(0,1) is an example of a hyperprior distribution. The notation of the distribution of Y changes as another parameter is added, i.e.

is called the hyperparameter, while its distribution given by N(0,1) is an example of a hyperprior distribution. The notation of the distribution of Y changes as another parameter is added, i.e.  . If there is another stage, say,

. If there is another stage, say,  follows another normal distribution with mean

follows another normal distribution with mean  and variance

and variance  , meaning

, meaning  ,

,

and

and  can also be called hyperparameters while their distributions are hyperprior distributions as well.[4]

can also be called hyperparameters while their distributions are hyperprior distributions as well.[4]

Framework

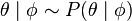

Let  be an observation and

be an observation and  a parameter governing the data generating process for

a parameter governing the data generating process for  . Assume further that the parameters

. Assume further that the parameters  are generated exchangeably from a common population, with distribution governed by a hyperparameter

are generated exchangeably from a common population, with distribution governed by a hyperparameter  . In frequentist statistics,

. In frequentist statistics,  and

and  are random effects and is a constant. In Bayesian statistics, however,

are random effects and is a constant. In Bayesian statistics, however,  and

and  are just random variables like any parameters.

are just random variables like any parameters.

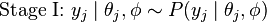

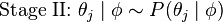

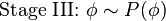

The Bayesian hierarchical model contains the following stages:

The likelihood, as seen in stage I is  , with

, with  as its prior distribution. Note that the likelihood depends on

as its prior distribution. Note that the likelihood depends on  only through

only through  .

.

The prior distribution from stage I can be broken down into:

-

[using Bayes’ Theorem]

[using Bayes’ Theorem]

With  as its hyperparameter with hyperprior distribution,

as its hyperparameter with hyperprior distribution,  .

.

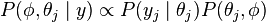

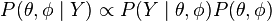

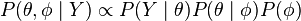

Thus, the posterior distribution is proportional to:

-

[using Bayes’ Theorem]

[using Bayes’ Theorem]

Example

To further illustrate this, consider the example:

A teacher wants to estimate how well a male student did in his SAT. He uses information on the student’s high school grades and his current grade point average (GPA) to come up with an estimate. His current GPA, denoted by Y, has a likelihood given by some probability function with parameter  , i.e.

, i.e.  . This parameter

. This parameter  is the SAT score of the student. The SAT score is viewed as a sample coming from a common population distribution indexed by another parameter

is the SAT score of the student. The SAT score is viewed as a sample coming from a common population distribution indexed by another parameter  , which is the high school grade of the student.[13] That is,

, which is the high school grade of the student.[13] That is,  . Moreover, the hyperparameter

. Moreover, the hyperparameter  follows its own distribution given by

follows its own distribution given by  , a hyperprior.

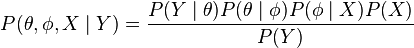

To solve for the SAT score given information on the GPA,

, a hyperprior.

To solve for the SAT score given information on the GPA,

All information in the problem will be used to solve for the posterior distribution. Instead of solving only using the prior distribution and the likelihood function, the use of hyperpriors gives more information to make more accurate beliefs in the behavior of a parameter.[14]

2-stage hierarchical model

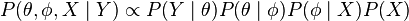

In general, the joint posterior distribution of interest in 2-stage hierarchical models is:

3-stage hierarchical model

For 3-stage hierarchical models, the posterior distribution is given by:

References

- 1 2 Allenby, Rossi, McCulloch (January 2005). “Hierarchical Bayes Model: A Practitioner’s Guide”. Journal of Bayesian Applications in Marketing, pp. 1–4. Retrieved 26 April 2014, p. 3

- ↑ Gelman, Andrew; Carlin, John B.; Stern, Hal S. and Rubin, Donald B. (2004). Bayesian Data Analysis (second ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 1-58488-388-X.

- ↑ Gelman 2004, p. 6

- 1 2 Gelman 2004, p. 117

- ↑ Good, I.J. (February 1980). “Some history of the hierarchical Bayesian methodology”. Trabajos de Estadistica Y de Investigacion Operativa Volume 31 Issue 1. Springer – Verlag, p. 480

- ↑ Good, I.J. (February 1980). “Some history of the hierarchical Bayesian methodology”. Trabajos de Estadistica Y de Investigacion Operativa Volume 31 Issue 1. Springer – Verlag, pp. 489–490

- ↑ Bernardo, Smith(1994). Bayesian Theory. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-92416-4, p. 23

- 1 2 Gelman 2004, pp. 6–8

- ↑ Bernardo, Degroot, Lindley (September 1983). “Proceedings of the Second Valencia International Meeting”. Bayesian Statistics 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V, ISBN 0-444-87746-0, pp. 167–168

- ↑ Gelman 2004, pp. 121–125

- 1 2 Diaconis, Freedman (1980). “Finite exchangeable sequences”. Annals of Probability, pp. 745–747

- ↑ Bernardo, Degroot, Lindley (September 1983). “Proceedings of the Second Valencia International Meeting”. Bayesian Statistics 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V, ISBN 0-444-87746-0, pp. 371–372

- ↑ Gelman 2004, pp. 120–121

- 1 2 3 Box G. E. P., Tiao G. C. (1965). "Multiparameter problem from a bayesian point of view". Multiparameter Problems From A Bayesian Point of View Volume 36 Number 5. New York City: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-57428-7