Battle of Werl (1586)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

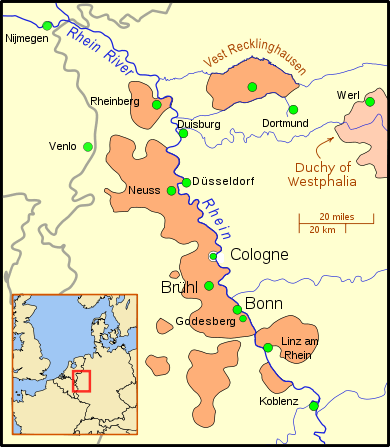

The Battle of Werl occurred between 3–8 March 1586, during a month-long campaign in the Duchy of Westphalia by mercenaries fighting for the Protestant (Calvinist) Archbishop-Prince Elector of Cologne, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg.

The action at Werl had been preceded by a general plundering of Vest and Recklinghausen by troops of Hermann Friedrich Cloedt and Martin Schenck which alienated the farmers and merchants of Westphalia from Gebhard's cause, although not specifically from Protestantism. Schenck used trickery to take the fortress at Werl, but was not able to completely overpower the guard. The arrival of a superior force outnumbering his by about 10 to 1, under the command of Claude de Berlaymont, cornered him in within the city's walls. In his subsequent withdrawal, he took a couple dozen civilian hostages, and escaped with his booty across the Rhine river.

Context

When Gebhard converted to Calvinism, married Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben in 1583, and declared religious parity for Protestants and Catholics in the electorate, the Cathedral chapter elected a competing archbishop, Ernst of Bavaria. Gebhardt refused to give up the ecclesiastical see, holding it with armed force where necessary; Ernst called in his brother, Ferdinand, for military assistance. Initially, the conflict was limited to troops of Waldburg, and the competing archbishop, Ernst of Bavaria. By 1585, these forces were stalemated, and each sought outside support, Waldburg from the Dutch and Ernst of Bavaria from the Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma.[1]

The Sack of Westphalia

In March 1586, Martin Schenck von Nydeggen took 500 foot and 500 horse to Westphalia, accompanied by Hermann Friedrich Cloedt, the commander of the fortified town of Neuss. Their goal was to secure two primary fortifications at Recklinghausen and Werl for Gebhard, and leave them fortified against attack by either Ernst's forces or those of the Duke of Parma. They crossed the Rhine river, and plundered several towns in Westphalia, including Hamm, Soest, Unna, Vest and Waltrop, as well as the farmsteads and villages between them. In the course of their campaign, they also desecrated several churches, removing all the icons, tapestries and furnishings, and, in Soest, harassing the clergyman.[2]

Cornered in Werl

After plundering Vest Recklinghausen, on 1 March Schenck captured Werl through trickery. He loaded a train of wagons with his soldiers and covered them with salt, a valuable commodity. When the wagons of salt were seen outside the city, the guards opened the gates they were admitted at once. The "salted soldiers" then over-powered the guards and captured the town.[3] Some of the defenders escaped to the Werl citadel. Schenck and his troops stormed it several times, but were turned away. When they could not capture the well-fortified citadel, they thoroughly sacked the city, theoretically to discourage any citizens from helping the guards in the citadel.[4]

Count Claude von Berlaymount, also known as Haultpenne, collected his force of 4000 and besieged Schenck in Werl, surrounding the city with heavy artillery and horse. Although he had a seemingly overwhelming force against Schenck's mere 500 or so soldiers, he was reluctant to shell the town. Although Schenck and Cloedt were surrounded outside, and attacked inside from the several hundred guards in the Werl citadel. They tried to break out once, but were forced back into the city, leaving some 50 of their own soldiers outside the gates when they were shut; these soldiers then escaped into the forest, and attacked several nearby farmsteads, waiting for their commanders to break out again.[5]

Inside the fortress Cloedt and Schenck loaded their wagons, this time with all their booty, took 30 magistrates as hostages, and attacked Haultpenne's force, killing about 500 of them, and losing 200 of their own. After fighting their way through Haultpenne's force, they made their way to Kettwick, and crossed the Rhine above Dortmund. Cloedt returned to his command at Neuss, which in a short time was surrounded and destroyed by Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma. Schenck to Venlo on the Neuss river.[6]

Result

For Schenck, the battle, and the campaign in Westphalia, was a success. He entered Westphalia as a soldier of fortune, and he left as a soldier with a fortune. Once he crossed the Rhine, he deposited his fortune and his wife in Venlo, and went to Delft to report to the Philip William, Prince of Orange. While there, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the English Governor-General of the Dutch, knighted him by order of Elizabeth I, and presented him with a chain valued at a thousand gold pieces.[7]

For Gebhard, the 1586 Battle of Werl specifically, and the sack of Westphalia generally, provided him with no specific gains and with some very concrete losses. Schenck failed to secure any reasonable fortresses for the long-term, which isolated Gebhardt's territories, and his forces, from any possible assistance from the Protestant princes in the east; they would have to fight through the Spanish army to send him any aid. The assets Schenck did acquire were largely plundered from farmers and merchants. Although they enhanced his and his soldiers' resources, they did little for Gebhard's declining financial situation, which, by this point, was in dire straits. Furthermore, little more than a paid brigand, Schenck alienated the population of Westphalia, if not from Protestantism at least from Gebhard's cause.[8]

In the larger picture of the Cologne War, the failure of the Westphalia campaign and Schenck's retreat from Werl marked the beginning of the end for Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg's tenure as archbishop and prince-elector of Cologne. Once the Spanish threw their army into the fray, the balance of military force shifted rapidly to the Catholic side. The loss of the archbishopric of Cologne to the Catholic contender, Ernst of Bavaria, resulted in the consolidation of Wittelsbach authority in northwestern German territories, the Jesuit-run establishment of a Catholic Counter-Reformation stronghold on the lower Rhine, and the consolidation of Spanish bridgeheads on the Rhine river, via which Philip of Spain could assault the Protestant Dutch provinces.[9]

Citations

- ↑ (German) L. Ennen, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne, 1863–1880. 21 July 2009.

- ↑ (German) Johann Heinrich Hennes, Der Kampf um das Erzstift Köln zur Zeit der Kurfürstenpublished 1878, pp. 156–162, 21 July 2009.

- ↑ Hennes, p. 157.

- ↑ Hennes, p. 158.

- ↑ Hennes, p. 158–59.

- ↑ Hennes, p. 159.

- ↑ Ernest Alfred Benians The Cambridge Modern History, New York, MacMillan, 1905, p. 708.

- ↑ Benians p. 708; Hennes, pp. 152–166.

- ↑ Benians p. 708; Holborn, Hajo (1959). A History of Modern Germany, The Reformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 252–246.