Battle of Monmouth

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

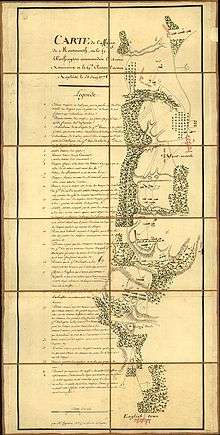

The Battle of Monmouth was an American Revolutionary War battle fought on June 28, 1778 in Monmouth County, New Jersey. The Continental Army under General George Washington attacked the rear of the British Army column commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton as they left Monmouth Court House (modern Freehold Borough). It is also known as the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse.

Unsteady handling of lead Continental elements by Major General Charles Lee had allowed British rearguard commander Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis to seize the initiative, but Washington's timely arrival on the battlefield rallied the Americans along a hilltop hedgerow. Sensing the opportunity to smash the Continentals, Cornwallis pressed his attack and captured the hedgerow in stifling heat. Washington consolidated his troops in a new line on heights behind marshy ground, used his artillery to fix the British in their positions, then brought up a four-gun battery under Major General Nathanael Greene on nearby Combs Hill to enfilade the British line, requiring Cornwallis to withdraw. Finally, Washington tried to hit the exhausted British rear guard on both flanks, but darkness forced the end of the engagement. Both armies held the field, but the British commanding general Clinton withdrew undetected at midnight to resume his army's march to New York City.

While Cornwallis protected the main British column from any further American attack, Washington had fought his opponent to a standstill after a pitched and prolonged engagement; the first time that Washington's army had achieved such a result. The battle demonstrated the growing effectiveness of the Continental Army after its six-month encampment at Valley Forge, where constant drilling under officers such as Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben and Major General Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette greatly improved army discipline and morale. The battle improved the military reputations of Washington, Lafayette and Anthony Wayne but ended the career of Charles Lee, who would face court martial at Englishtown for his failures on the day. According to some accounts, an American soldier's wife, Mary Hays, brought water to thirsty soldiers in the June heat, and became one of several women associated with the legend of Molly Pitcher. By the second phase of the battle the temperature remained almost consistently above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and heat stroke was said to have claimed more lives than musket fire throughout the battle.[4]

Background

British forces had captured Philadelphia in 1777. In May 1778, the British commander-in-chief in North America, General Sir Henry Clinton, was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia and concentrate his troops at the main British base in New York City as France had entered the war on the side of the Americans. Clinton was ordered to dispatch units to West Florida and the West Indies which left him too few troops to continue occupying Philadelphia. Clinton was also ordered to abandon New York and withdraw to Quebec if he felt his position there was untenable.[5] A French fleet under d'Estaing had sailed from Toulon in April, 1778 and intended to make a rendezvous with rebel forces which could threaten Clinton's army before it reached the safety of New York.

It was originally intended that the withdrawing British army would travel directly to New York via the sea, escorted by the Royal Navy. A lack of transports forced Clinton to change his plans. While the stores, heavy equipment and Loyalist American civilians fleeing revenge attacks would be shipped by sea, the main army would march overland across New Jersey.[6]

On June 18, the British began to evacuate Philadelphia, and began their approximately 100-mile (160 km) march to the northeast across New Jersey to New York City. The British force comprised 11,000 British and German regulars, a thousand Loyalists from Philadelphia, and a baggage train 12 miles (19 km) long. As the British advanced, the Americans slowed their advance by burning bridges, muddying wells and building abatis across the roads.

Prelude

With a high of over 100 °F (37.8 °C), both sides lost almost as many men to heat stroke as to the enemy. Major General Charles Lee, Washington's second-in-command, advised awaiting developments as he did not wish to commit the American force against the British regulars. However, Washington determined that the British column was vulnerable to attack as it traveled across New Jersey with its baggage train, and moved from Valley Forge in pursuit.

Washington was still undecided how to attack the British column, and held a council of war. The council, however, was divided on the issue; with a small group of officers including General Anthony Wayne urging a partial attack on the British column while it was strung out on the road. Lee was still cautious, advising only harassing attacks with light forces. On June 26, 1778, Washington chose to send 4,000 men as an advance force to strike at the British rear guard as they departed Monmouth Courthouse, in order to delay the British withdrawal until the main American force could give battle.

Battle

Lee, as Washington's senior subordinate, was initially appointed commander of the advance force, but turned it down because of his doubts about the plan. However, when the force was increased to 5,000 and the command offered to the Marquis de Lafayette, Lee changed his mind and insisted on the command.

Lee met with his subordinates but failed to give them proper orders, resulting in a piecemeal and disorganized attack on June 28 against the British rear guard under General Charles Cornwallis. After several hours of fighting in the hot weather, several American brigades executed a tactical retreat, which developed into a general withdrawal. The British rear guard counterattacked and Lee ordered a retreat, which rapidly became a rout.

Washington, advancing with the main force along the Monmouth road, encountered Lee's fleeing troops and finally Lee himself, with the British in hot pursuit. After a heated exchange with Lee, Washington relieved him of command and sent him to the rear. He then rallied Lee's troops, who delayed the British pursuit until the main force could take up positions further to the west.

The remnants of Lee's forces then withdrew to the main American force, where the Continental Army troops were positioned behind the West Ravine on the Monmouth Courthouse - Freehold Meeting House Road. Washington drew up his army with Greene's division on the right, Major General Stirling's division on the left, and most of Lee's former force, now under Lafayette, in reserve. In front of his lines, Wayne commanded various elements of Lee's force. Artillery was placed on both wings, with the right wing in position to enfilade the advancing British.

The British came on and attacked Stirling's left wing with their light infantry and the 42nd (Black Watch) Regiment in the van. They were met by a storm of fire from Stirling's Continentals. The battle raged back and forth for an hour until three American regiments were sent though woods to enfilade the attacking British right flank. The attack was successful and sent the British back to reform.

Foiled on the left, Cornwallis personally led a heavy attack against Greene's right wing, with a force comprising British and Hessian grenadiers, light infantry, the Coldstream Guards and another Guards battalion, and the 37th and 44th Regiments. The attack was met by enfilading fire from Thomas-Antoine de Mauduit du Plessis's four 6-pound cannons on Combs Hill, as well as accurate volleys from Greene's Continental regiments. The British persisted up the ravine slope but within minutes five high-ranking officers and many men were down from heavy fire. The attackers recoiled down the slope.

During Cornwallis' abortive attack on Greene, another British force made up of grenadiers, light infantry and light dragoons hit Wayne's forward force, who were protected behind a long hedge. Three times the British were driven back by Wayne's grapeshot and bullets: but an overwhelming fourth attack overlapped Wayne's position and forced his units to fall back to the main American line.

The British made no further attempts on the main American line, although cannonading from both sides continued until 6 p.m. At this point, the British fell back to a strong position east of the Ravine. Washington wanted to take the offensive to the British and attack both flanks, but darkness brought an end to the battle.

The British rested and then resumed their march to the northeast during the night. Washington wanted to resume the battle the next day but in the morning found that the British had withdrawn during the night, continuing their march without incident to Sandy Hook and arriving there on June 30. The British force was then transported by the Royal Navy across Lower New York Bay to Manhattan.

The battle was a tactical British victory, as the rearguard successfully covered the British withdrawal. The battle effectively ended in a draw, as the Americans held their ground, but the British were able to get the army and supplies safely to New York.[7]

The British official casualty return reported 65 killed, 59 dead of "fatigue", 170 wounded and 64 missing.[8] The American official return stated 69 killed, 161 wounded and 132 missing (37 of whom were found to have died of heat-stroke).[2] Other estimates increase the losses to 1,134 British and 500 American casualties.[2]

Aftermath

After the battle the British continued their march eastwards until they reached Sandy Hook. From there they were taken by boat to New York City where they began preparing the city's defenses in expectation of an attack. D'Estaing's fleet arrived just too late, narrowly missing a chance to trap Clinton's army at Sandy Hook.[9] Plans to attack New York were abandoned, and it remained the principal base for British forces until 1783. Instead D'Estaing sailed north to participate in a Franco-American assault on the British garrison at Newport, Rhode Island, which ended in failure. Monmouth was the last major battle in the northern theater, and the largest one-day battle of the war when measured in terms of participants. Lee was later court-martialed at the Village Inn located in the center of Englishtown,[10] where he was found guilty and relieved of command for one year. The verdict was approved by the Continental Congress by a close vote. Many months later, Lee wrote a strongly worded letter to Congress in protest but Congress closed the affair by informing him that it had no more need of his services. Lee never held another military command and died in 1782.

Legacy

The legend of "Molly Pitcher" is usually associated with this battle. It is believed that she was Mary Ludwig Hays. According to one story, she was the wife of an American artilleryman who lived near the battlefield, bringing water for swabbing the cannons and for the thirsty crews, and took her husband's place after he fell, and helped him with his wounds. The artillery men gave her the nickname "Molly Pitcher" when she was bringing them water from a nearby spring. The story is based on a true incident but has become embellished over the years. Two places on the battlefield are marked as sites of the "Molly Pitcher Spring".[11]

Nine Army National Guard units (101st Eng Bn,[12] 101st FA,[13] 113th Inf[14] 116 Inf,[15] 125th QM Co,[16] 175th Inf,[17] 181st Inf,[18] 198th Sig Bn[19] and 211 MP Bn[20]) and one active Regular Army Field Artillery battalion (1-5th FA[21] ) are derived from American units that participated in the Battle of Monmouth. There are only thirty currently active units of the U.S. Army with lineages that go back to the colonial era.

Although never accorded formal preservation, the Monmouth Battlefield is one of the best preserved of the Revolutionary War battlefields.[11] Each year, during the last weekend in June, the Battle of Monmouth is reenacted at Monmouth Battlefield State Park in modern Freehold Township and Manalapan.

The Monmouth County Historical Association at 70 Court Street in Freehold Borough, New Jersey houses a collection of documents which includes personal accounts, journals, pension applications, letters, and miscellaneous printed material.

See also

References

- 1 2 Martin p.199

- 1 2 3 Martin p.233

- ↑ Martin p.232-233

- ↑ "Battle of Monmouth Courthouse". Robinson Library. Self-published. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Gaines p.109

- ↑ Syrett p.75-76

- ↑ "American revolution History". History Channel. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ Martin p.232

- ↑ Ferling p.308-309

- ↑ A Short History of the Borough of Englishtown, accessed December 26, 2006

- 1 2 Monmouth Battlefield: Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, accessed November 3, 2006

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 101st Engineer Battalion

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 101st Field Artillery.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 113th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 221–223.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 116th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 227–229.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 125th Quartermaster Company. http://states.ng.mil/sites/MA/News/Pages/125th%20Quartermaster%20Company%20honored%20for%20storied%20lineage%20and%20service%20at%20Lexington%20and%20Concord.aspx

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 175th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1982, pp. 343–345.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 181st Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 354–355.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 198th Signal Battalion.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, HHD/211th Military Police Battalion.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery.http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/fa/0005fa01bn.htm.

Bibliography

- Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Gaines, James R. For Liberty and Glory: Washington, Lafayette and their Revolutions. W.W. Norton & Co, 2007.

- Martin, David G., The Philadelphia Campaign: June 1777–July 1778. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Books, 1993. ISBN 0-938289-19-5. 2003 Da Capo reprint, ISBN 0-306-81258-4.

- Sawicki, James A. Infantry Regiments of the US Army. Dumfries, VA: Wyvern Publications, 1981. ISBN 978-0-9602404-3-2.

- Syrett, David. Admiral Lord Howe: A Biography. Spellmount, 2006.

- Ward, Christopher, The War of the Revolution. 2 Volumes. New York: MacMillan, 1952.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Monmouth. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Monmouth, Battle of. |

- Battle of Monmouth overview

- Monmouth Battlefield: Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

- Monmouth County Historical Association: Coll. 72 Battle of Monmouth Collection

- Battle of Monmouth

- Department of Military Science - Battle of Monmouth

- Styker, William (2006). The Battle of Monmouth. Kessinger Publishing. p. 336. ISBN 1-4286-1600-4.

- Wade, David (June 1998). "Battle of Monmouth". Military History. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- Irving, Washington (1888). Fiske, John,, ed. Washington and his country: being Irving's life of Washington,... Ginn & Co. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- Bohrer, Melissa Lukeman (2003). Glory, Passion and Principle: The Story of Eight Remarkable Women at the Core of the American Revolution. Simon & Schuster. p. 162. ISBN 0-7434-5330-1. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- Veit, Richard Francis (2002). Digging New Jersey's past: historical archaeology in the Garden State. Rutgers University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0-8135-3113-6. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- Lodge, Henry Cabot (1903). The Story of the Revolution. Scribners. p. 324. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- Battle of Monmouth Animation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||