Battle of Maysalun

| Battle of Maysalun معركة ميسلون | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Syrian War | |||||||

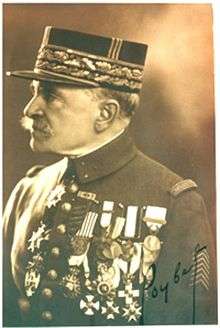

French General Henri Gouraud on horseback inspecting his troops at Maysalun | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000 troops (backed by tanks and aircraft) | 1,400–3,000 regulars, Bedouin cavalrymen, civilian volunteers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 24 killed (French claim)[1] |

~150 killed (French claim) ~1,500 wounded (French claim)[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Maysalun (Arabic: معركة ميسلون), also called the Battle of Maysalun Pass, was a battle fought between the forces of the Arab Kingdom of Syria and French Army of the Levant on 24 July 1920 near the Maysalun Pass, about 12 miles west of Damascus, close to the Lebanese border.

Prior to the engagement at Maysalun, the French general, Henri Gouraud, had given King Faisal an ultimatum to disband his newly formed army, a demand to which Faisal ultimately acceded. However, by the time Faisal communicated his agreement, French forces had launched an offensive towards Damascus from Lebanon, and Faisal's war minister, General Yusuf al-'Azma set out to confront them with remnants of the Arab Army and Damascene volunteers. During the battle, the better-equipped French forces under the command of General Mariano Goybet defeated the Syrian forces of al-'Azma, who was killed in action.

French troops entered Damascus the following day, encountering little resistance. Soon after, Faisal was expelled from Syria. Despite the Arab Army's decisive defeat, the Battle of Maysalun became a symbol, in Syria and the Arab world, of desperate courage against a stronger imperial power.

Background

Towards the end of World War I and as part of the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, the Sharifian Army led by Emir Faisal, backed by the British Army, captured Damascus from the Ottomans on 30 October 1918. In correspondences between the Sharifian leadership and the British, the latter promised to support the establishment of a Sharifian kingdom in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire in return for launching a revolt against the Ottomans.[2] However, the British and French governments made previous arrangements regarding the division of the Ottomans' Arab provinces between themselves in the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement.[3]

To allay his fears regarding his throne in Syria, Faisal attended the January 1919 Paris Conference, where he was not recognized by the French government as the King of Syria. Faisal called for Syrian sovereignty under his rule,[3] but the European powers attending the conference called for European mandates to be established over the Ottomans' former Arab territories.[4] In the US-led June 1919 King–Crane Commission, the commission concluded in 1922 that the people of Syria overwhelmingly rejected French rule and Emir Faisal stated to the commission that "French rule would mean certain death to Syrians as a distinguished people".[5] French forces commanded by General Henri Gouraud landed in Beirut on 18 November 1919, with the ultimate goal of bringing all of Syria under French control. Shortly thereafter, French forces deployed to the Beqaa Valley, an area between Beirut and Damascus. Against King Faisal's wishes, his delegate to General Gouraud, Nuri al-Said, agreed to the French deployment. However, when a French officer was assaulted by Shia Muslim rebels opposed to the French presence, Gouraud violated his agreement with al-Said and occupied the large town of Baalbek. The French deployment along the Syrian coast and the Beqaa Valley provoked unrest throughout Syria and sharpened political divisions between the political camp that called for confronting the French and the camp that sought compromise with the French.[6]

Faisal proclaimed himself king of the independent Kingdom of Syria on 8 March 1920.[7] This unilateral action was immediately repudiated by the British and French and the San Remo Conference was called by the Allied Powers in April 1920 to finalize the allocation of mandates in the Arab territories. This was, in turn, repudiated by Faisal and his supporters. After months of instability and failure to make good on the promises Faisal had made to the French, General Gouraud gave an ultimatum to Faisal on 14 July 1920 demanding that he disband the Arab Army and submit to French authority by 20 July or face a French military invasion.[8][9] On 18 July, Faisal and the entire cabinet, with the exception of War Minister Yusuf al-'Azma, agreed to the ultimatum and issued disbandment orders for the Arab Army units at Anjar, the Beirut–Damascus road and the hills of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains overlooking the Beqaa Valley.[10] Two days later, Faisal informed the French liaison in Damascus of his acceptance of the ultimatum, but for unclear reasons, Faisal's notification did not reach Gouraud until 21 July. Sources suspicious of French intentions accused the French of intentionally delaying delivery of the notice to give Gouraud an official excuse for advancing on Damascus.[11] However, there has been no evidence or indication of French sabotage.[10] News of the disbandment and Faisal's submission led to riots in Damascus and their suppression by Emir Zeid, which led to around 200 deaths.[12] Al-'Azma, who was staunchly opposed to surrender, implored Faisal to give him and the remnants of his army the opportunity to confront the French.[13]

Combatants and arms

French forces

The forces of the French Army of the Levant amounted to some 12,000 troops.[1][12] The troops were mostly made up of Senegalese and Algerian units,[1] and consisted of ten infantry battalions and a number of cavalry and artillery units.[12] Among the participating units were the 415th Infantry Regiment, the 2nd Algerian Riflemen Regiment, the Senegalese Division, the African Riflemen Regiment and the Moroccan Sipahi Battalion.[14] A number of Maronite volunteers from Mount Lebanon reportedly joined the French forces as well.[15] The Army of the Levant was equipped with plain and mountain artillery batteries and 155mm guns,[14] and backed by tanks and fighter bombers.[12] The commander of the French forces was General Mariano Goybet.[14]

Syrian forces

The Syrian forces that fought in the battle consisted of the remnants of General Hassan al-Hindi's disbanded Arab Army unit based in Anjar, a force of Arab Army regulars from disbanded units in Damascus, Bedouin camel-mounted soldiers assembled by General al-'Azma, and numerous civilian volunteers and militiamen.[12] Estimates put the number of Arab Army soldiers and local irregulars at 3,000 or 4,500.[1] Most Arab Army units had already been disbanded days prior to the battle by order of King Faisal as part of his acceptance of the terms set out in General Gouraud's 14 July ultimatum.[10] According to historian Eliezer Tauber, of the 3,000 soldiers and volunteers al-'Azma recruited, only 1,400 fighting men actually showed up to the battle.[16]

Part of the civilian militia units were assembled and led by Yasin Kiwan, a Damascene merchant, Abd al-Qadir Kiwan, the former imam of the Umayyad Mosque, and Shaykh Hamdi al-Juwajani, a Muslim scholar. Yasin and Abd al-Qadir were killed during the battle.[17] Shaykh Muhammad al-Ashmar also participated in the battle with 40–50 of his men from the Midan quarter of Damascus. Other Muslim preachers and scholars from Damascus, including Tawfiq al-Darra (ex-mufti of the Ottoman Fifth Army), Sa'id al-Barhani (preacher at the Tuba Mosque), Muhammad al-Fahl (scholar from the Qalbaqjiyya Madrasa) and Ali Daqqar (preacher at the Sinan Pasha Mosque) also participated in the battle.[18]

The Syrians were equipped with rifles discarded by retreating Ottoman soldiers during World War I and those used by the Sharifian Army's Bedouin cavalry during the 1916 Arab Revolt. The Syrians also possessed a number of machine guns and about 15 artillery batteries. According to various versions, ammunition was low, with 120–250 bullets per rifle, 45 bullets per machine gun, and 50–80 shells per cannon. Part of this ammunition was also unusable because many bullet and rifle types did not correspond to each other.[9]

Battle

On 23 July al-'Azma set out from Damascus with his forces who were divided into northern, central and southern columns each headed by camel cavalry units.[19] French forces launched their offensive towards the Maysalun Pass and Wadi al-Qarn on 24 July shortly after dawn, at 5:00.[19] The first clashes took place at 6:30 when French tank divisions stormed the central position of the Syrian defensive line while French cavalry and infantry units assaulted the Syrians' northern and southern positions.[20] The Syrians' camel cavalry were the first Syrian units to engage the French.[19] Syrian forces initially put up stiff resistance along the front,[19][21] but lacked coordination between their different units.[19] At one point early in the battle, they managed to briefly surround two Senegalese units.[21] French artillery took a toll on the Syrians and by 8:30 am the French had broken the Syrians' central trench.[19] By 10:00, the battle was effectively over.[21]

At 10:30, French forces reached al-'Azma's headquarters, unhindered by the mines en route that had been laid out by the Syrians. According to one version, when French forces were about 100 meters in the distance, al-'Azma rushed to a Syrian artilleryman stationed near him and demanded him to open fire. However, before any shells could be fired, a French tank unit spotted al-'Azma and gunned him down with machine gun fire.[19] In another account of events, al-'Azma had attempted to mine the trenches as the French forces approached his position, but was shot down by the French before he could set off the charges.[21] Al-'Azma's death virtually marked the end of the battle, although intermittent clashes continued until 13:30.[19] Retreating Syrian forces were bombed from the air and harried by the French on their way toward Damascus.[21]

After the battle, General Gouraud addressed General Goybet as follows:

GENERAL ORDER No. 22

Aley, 24 July 1920

- "The General is deeply happy to address his congratulations to General Goybet and his valiant troops: 415th of line, 2nd Algerian sharpshooters, 11th and 10th Senegalese sharpshooters, light-infantry-men of Africa, Moroccan trooper regiment, batteries of African groups, batteries of 155, 314, company of tanks, bombardment groups and squadrons who in the hard fight of 24 of July, have broken the resistance of the enemy who defied us for 8 months ... They have engraved a glorious page in the history of our country." – General Gouraud

Aftermath

Initial estimates of the casualties which claimed 2,000 Syrian dead and 800 French casualties turned out to be exaggerated.[19] The French Army claimed 24 of its soldiers were killed, while around 150 Syrian fighters were killed and 1,500 wounded.[1] King Faisal observed the battle unfold from the village of al-Hamah, and as it became apparent that the Syrians had been routed, he and the Syrian cabinet, with the exception of Interior Minister 'Ala al-Din al-Durubi, who had quietly secured a deal with the French, departed for al-Kiswah, a town located at the southern approaches of Damascus.[21]

French forces had captured Aleppo on 23 July without a fight,[21] and after their victory at Maysalun, General Goybet's troops besieged and captured Damascus on 25 July. Within a short time, the majority of Faisal's forces fled or surrendered to the French, although parties of Arab groups opposed to French rule continued to resist before being quickly defeated.[9] King Faisal returned to Damascus on 25 July and asked al-Durubi to form a government, although al-Durubi had already decided on the composition of his cabinet, which was confirmed by the French. General Gouraud condemned Faisal's rule in Syria, accusing him of having "dragged the country to within an inch of destruction", and stating that because of this, it was "utterly impossible for him to remain in the country".[22] Faisal denounced Gouraud's statement and insisted that he remained the sovereign head of Syria whose authority he was "granted by the Syrian people".[22] Although he verbally dismissed the French order expelling him and his family from Syria, Faisal departed the country on 27 July with only one of his cabinet members, Education Minister Sati al-Husri.[22]

Legacy

The French took control of the territory that became the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon. France divided Syria into smaller statelets centered on certain regions and sects, including Greater Lebanon for the Maronites, Jabal al-Druze State for the Druze in Hauran, the Alawite State for the Alawites in the Syrian coastline and the states of Damascus and Aleppo.[23] Gouraud reportedly went to the tomb of Saladin, kicked it, and said: "Awake, Saladin. We have returned. My presence here consecrates victory of the Cross over the Crescent."[24]

Although the Syrians were decisively defeated, the Battle of Maysalun "has gone down in Arab history as a synonym for heroism and hopeless courage against huge odds, as well as for treachery and betrayal", according to Iraqi historian Ali al-Allawi.[21] According to British journalist Robert Fisk, the Battle of Maysalun was "a struggle which every Syrian learns at school but about which almost every Westerner is ignorant".[25] Historian Tareq Y. Ismael wrote that following the battle, the "Syrian resistance at Khan Maysalun soon took on epic proportions. It was viewed as an Arab attempt to stop the imperial avalanche." He also states that the Syrians' defeat caused popular attitudes in the Arab world that exist until the present day which hold that the Western world dishonors the commitments it makes to the Arab people and "oppresses anyone who stands in the way of its imperial designs."[26] Sati' al-Husri, a major pan-Arabist thinker, asserted that the battle was "one of the most important events in the modern history of the Arab nation."[27] The event was annually commemorated by Syrians, during which thousands would visit the grave of al-'Azma in Maysalun.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bidwell, p. 269.

- ↑ Moubayed 2012, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 Moubayed 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Moubayed 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Moubayed 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Allawi, 2014, p. 285.

- ↑ Allawi 2014, p. 260.

- ↑ Moubayed 2006, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Tauber 1995, p. 215.

- 1 2 3 Allawi 2014, p. 288.

- ↑ Tauber 2013, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allawi 2014, p. 289.

- ↑ Moubayed 2006, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Husri 1966, p. 172.

- ↑ Salibi, Kamal S. (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I. B. Tauris. p. 33. ISBN 9781860649127.

At the battle of the Maysalun Pass, in the Anti-Lebanon, the French did crush the forces of King Faysal in July 1920, which finally opened the way for their occupation of Damascus. Maronite volunteers reportedly fought with the French in the battle, and there were open Maronite celebrations of the French victory, or rather of the Arab defeat. This was not to be forgotten in Damascus.

- ↑ Tauber 1995, p. 216.

- ↑ Gelvin 1998, p. 115.

- ↑ Gelvin 1998, pp. 115–116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tauber 1995, p. 218.

- ↑ Allawi 2014, p. 290.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Allawi 2014, p. 291.

- 1 2 3 Allawi 2014, p. 292.

- ↑ McHugo 2013, p. 122.

- ↑ Meyer, Karl Ernest; Brysac, Shareen Blair (2008). Kingmakers: The Invention of the Modern Middle East. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 359. ISBN 9780393061994.

- ↑ Fisk 2007, p. 1003.

- ↑ Ismael 2014, p. 57.

- 1 2 Sorek 2015, p. 32.

Bibliography

- Allawi, Ali A. (2014). Faisal I of Iraq. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300127324.

- Fisk, Robert (2007). The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307428714.

- Gelvin, James L. (1998). Divided Loyalties: Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire. California University Press. ISBN 9780520919839.

- Husri, Sati' (1966). The Day of Maysalūn: A Page from the Modern History of the Arabs. Middle East Institute.

- Ismael, Tareq Y. (2014). The International Relations of the Contemporary Middle East: Subordination and Beyond. Routledge. ISBN 9781135006914.

- McHugo, John (2013). A Concise History of the Arabs. The New Press. ISBN 9781595589460.

- Moubayed, Sami (2006). Steel and Silk. Cune Press. ISBN 1885942419.

- Sorek, Tamir (2015). Palestinian Commemoration in Israel: Calendars, Monuments, and Martyrs. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804795180.

- Tauber, Eliezer (1995). The Formation of Modern Iraq and Syria. Routledge. ISBN 9781135201180.

Further reading

- Moubayed, Sami M. The Politics of Damascus 1920–1946. Urban Notables and the French Mandate (Dar Tlass, 1999)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 33°35′44″N 36°3′53″E / 33.59556°N 36.06472°E