Battle of Huoyi

| Battle of Huoyi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the transition from Sui to Tang | |||||||

Map of the situation in China during the transition from the Sui to the Tang, with the main contenders for the throne and the main military operations by the Tang and their various rivals | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Li Yuan's forces | Sui Dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Li Yuan Li Shimin Li Jiancheng | Song Laosheng (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ca. 25,000[1] | 20,000 or 30,000[2] | ||||||

| ||||||

The Battle of Huoyi (霍邑之戰; Wade-Giles: Huo-i) was fought in China on 8 September 617 between the forces of the rebel Duke of Tang, Li Yuan, and the army of the ruling Sui Dynasty. Li Yuan, with an army of ca. 25,000, was advancing south along the Fen River towards the imperial capital, Daxingcheng. His advance was stalled for two weeks due to heavy rainfall and he was met at the town of Huoyi by an elite Sui army of 20,000 (or 30,000) men. Li Yuan's cavalry, under the command of his two eldest sons, lured the Sui out of the protection of the city walls, but in the first clash between the two main armies, Li Yuan's forces were initially driven back. At that point, possibly due to a stratagem on Li Yuan's behalf, the arrival of the rest of the rebel army, or to the flanking manoeuvres of Li Yuan's cavalry, which had gotten behind the Sui army, the Sui troops collapsed and routed, fleeing back towards Huoyi. Li Yuan's cavalry, however, cut off their retreat. The battle was followed by the capture of weakly defended Huoyi, and the advance on Daxingcheng, which fell to the rebels in November. In the next year, Li Yuan deposed the Sui and proclaimed himself emperor, beginning the Tang Dynasty.

Background

During the later reign of the second emperor of the Sui Dynasty, Yang, the dynasty's authority began to wane. The main reason was the immense material and human cost of the protracted and fruitless attempts to conquer the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo. Coupled with natural disasters, the conscription of more and more men for the war and the hoarding of scarce grain reserves for the army's needs increased provincial discontent.[3][4][5] As a result, from 611 on rural revolts broke out across the empire, and with the emperor's prestige and legitimacy diminished by military failure, ambitious provincial magnates were encouraged to challenge his rule. Yang nevertheless continued to be fixated on the Korean campaigns, and only as unrest spread within the Empire and the powerful Eastern Turks turned hostile, did he realize the gravity of the situation: in 616, he abandoned the north and withdrew to Jiangdu, where he remained until his assassination in 618.[6][7][8]

With the emperor's withdrawal from the scene, local governors and magnates emerged to claim power. Nine major contenders emerged, some claiming the imperial title for themselves, others, like Li Mi in Henan, contending themselves, for the time being, with more modest titles.[9] Among the most well-positioned contenders was Li Yuan, Duke of Tang and governor of Taiyuan in the northwest (modern Shanxi). A scion of a noble family related to the Sui dynasty, and with a distinguished career behind him, Li Yuan was an obvious candidate for the throne. His province possessed excellent natural defences, a heavily militarized population and was located near the capitals of Daxingcheng (Chang'an) and Luoyang.[10][11]

Li Yuan's march south

Traditional historiography emphasizes Li Yuan's initial reluctance to revolt against the Sui, and that he had to be persuaded by his senior aides and his second son (and eventual successor), Li Shimin. In reality, Li Yuan was considering a rebellion at least by the time of his appointment to Taiyuan in early 617. In mid-617, Li began raising additional troops from his province and executed his two deputies—who were appointed by emperor Yang to watch over him. He also concluded an alliance with Shibi, the powerful khagan of the Eastern Turks, which secured his northern frontier from a Turkish invasion and provided him with men and, most importantly, horses, which he lacked.[12][13] Initially, however, Li Yuan portrayed himself a Sui loyalist, and proclaimed his intention of placing Yang's grandson, Yang You, on the throne.[14]

Li Yuan's campaign is recorded in detail by his chief secretary, Wen Daya.[15] In mid-July, a first expedition, under Li Yuan's eldest sons Li Jiancheng and Li Shimin, was launched against the loyalist Xihe commandery further south along the Fen River. Li Yuan's sons succeeded in capturing the province within a few days and returned to Taiyuan.[16] Finally, after his preparations were complete, on 10 August, Li Yuan began his march south, along the Fen towards Daxingcheng. His "righteous army" comprised 30,000 men, raised from the local "soaring hawk" militia, but with some 10,000 additional volunteers and including a 500-strong Turkish contingent, provided by the khagan along with 2,000 horses. His fifteen-year-old son Li Yuanji was left behind to guard Taiyuan, while Li Jiancheng and Li Shimin accompanied their father as his lieutenants. A small force under Chang Lun was detached to advance parallel to the main army and capture the loyalist commanderies further west, securing the flanks.[14][17]

Li Yuan's advance was stopped at a place called Guhubao for two weeks in late August due to heavy rainfall, giving time to the Sui authorities to react: the general Qutu Tong was sent to secure Hedong Commandery on the Yellow River, while another army, of 20,000 elite troops under Song Laosheng advanced north to the town of Huoyi, some 17 miles south of Guhubao, to confront him. Huoyi was placed on the southern exit of a defile through which the road passed, following the course of the Fen River, and provided an excellent position from which to check an army coming from the north. When Li Yuan's army learned of Song Laosheng's presence, some began advocating a retreat to Taiyuan, fearing that in their absence the Turks might break the treaty and attack it. A council was held, at which Li Yuan sided with his sons, who argued forcefully for continuing the campaign. Thus, on 8 September, after the rains stopped, Li Yuan's army set out from its encampment. Instead of following the road through the defile, however, they chose a path through the southeastern hills, allegedly revealed to them by a peasant.[18]

Li Yuan's army that arrived at Huoyi numbered less than its original 30,000 men, perhaps as few as 25,000, due to the detachments left behind. It was predominantly composed of infantry was divided into six divisions under a general (tongjun), but it is unclear how they were subordinated to Li Yuan and his sons: Li Jiancheng and Li Shimin were named in the traditional fashion as commanders of the left and right respectively, but in the accounts of the battle, the army appears formed in van, middle and rear divisions. The cavalry, a few hundred strong, was apparently kept as a strategic reserve. Very little is also known about the Sui army, except that Song Laosheng's troops were considered to be elite warriors. Some sources raise their number to 30,000 from the more typical 20,000; this could be an error, or possibly indicate additional forces recruited at Huoyi.[19]

There are two accounts of the subsequent battle: the account of Wen Daya, and a later official account, which became the dominant version in traditional Chinese historiography. The latter was compiled during the reign of Li Shimin, and therefore enhances his own role, having him decide the battle in a cavalry charge, while denigrating the role of both his father and his elder brother Li Jiancheng, whom Li Shimin would murder and supplant on the throne. The two accounts are difficult to reconcile, but Wen Daya's account, despite its own inadequacies, is clearly to be preferred as an eyewitness testimony.[20][21] According to Wen Daya, Li Yuan feared that Song Laosheng would deny battle and instead force him to engage in a prolonged and costly siege of the town. For this reason, as soon as the headquarters with the cavalry cleared the hills and came into view of Huoyi in the early afternoon of 8 September, Li Yuan sent his sons at the head of the cavalry to manoeuvre before the walls of Huoyi, hoping to entice the Sui army to come out. In this he hoped to exploit Song Laosheng's reputation for rashness. The slower-moving infantry, which formed bulk of Li Yuan's army, was still in the process of traversing the hills, and Li Yuan sent officers to hurry them up. Song Laosheng, who may have seen this as an opportunity of destroying his enemy piecemeal, deployed his army outside the town wall, but proved reluctant to advance further, and had to be goaded further away from the town through a feigned retreat by the cavalry.[22]

At this time, Li Yuan's infantry began arriving, with the van division deploying in a square to fend off a Sui attack while the other two divisions were coming up behind it. Wen Daya's account now becomes sketchier, indicating that the infantry charged the Sui army, at which point Li Yuan's sons led the cavalry around the Sui flank towards the town, where the small garrison left behind by Song Laosheng was forced to drop the portcullis gates. Li Yuan then let spread the rumour that Song Laosheng had been killed, which demoralized the Sui force. The Sui army began to retreat, but this turned into a rout when they found their retreat to Huoyi cut off by Li Yuan's cavalry and the barred gates.[23] Wen Daya's narrative can be supplemented by the later account, which, despite its bias regarding Li Shimin, also contains indications that not everything went according to Li Yuan's plans: it appears that in the first clash between Li Yuan's infantry and the Sui army, the Sui had the upper hand and pushed Li Yuan back, possibly because he had not yet managed to bring all his forces into the field. Either through the arrival of the rest of Li Yuan's infantry, the actions of Li Yuan's cavalry along and behind the Sui flanks, or Li Yuan's stratagem, the Sui army's morale gave way abruptly, and their resistance collapsed.[24]

The battle was over by 4 p.m. in a crushing victory for Li Yuan, who then led his troops against Huoyi itself. Although he lacked any siege equipment, the garrison in the town was too small to effectively resist Li Yuan's army, and Huoyi fell within a few hours.[25]

Aftermath

Following their victory, Li Yuan and his army continued their southward advance, and in mid-October reached the Yellow River. Part of the army was left behind to contain the Sui garrison at Puzhou, while the rest crossed the river, defeating a Sui army that tried to prevent them. The governor of Huazhou surrendered the city and its vital granaries to him, and turned towards the capital. On the way, he was joined by his daughter, Princess Pingyang, and his cousin, Li Shentong, with the troops they had raised themselves. By the time Li Yuan's army reached Daxingcheng, it was said to number 200,000 men. After a brief siege, on 9 November, Li Yuan's troops stormed the capital.[26]

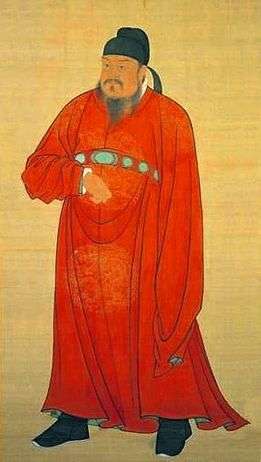

This feat established Li Yuan as a major contender for the empire, but for the moment, despite the calls of his generals to proclaim himself emperor there and then, he still feigned to be a Sui loyalist: the Sui imperial family was kept safe and its dignity respected, and the young Yang You was enthroned as emperor Gong, with Yang himself delegated to the honorific position of "Retired Emperor" (taishang huang). It was not until 16 June 618, exactly a year after he formally broke with Sui by executing his deputies, that Li Yuan deposed the puppet emperor and proclaimed himself the first emperor of the Tang Dynasty, with the temple name of Gaozu.[11][27] The new dynasty still had to face the various local rebels and warlords that had sprung up throughput the Chinese Empire, but by 628,with a judicious mixture of force and clemency, the Tang had succeeded in the pacification and consolidation of China under their rule.[28][29]

References

- ↑ Graff (1992), p. 42

- ↑ Graff (1992), p. 43

- ↑ Wright (1979), pp. 143–147

- ↑ Graff (2002), pp. 145–153

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 153

- ↑ Wright (1979), pp. 143–148

- ↑ Graff (2002), pp. 153–155

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), pp. 152–153

- ↑ Graff (2002), pp. 162–165

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), pp. 150–154

- 1 2 Graff (2002), p. 165

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), pp. 154–158

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 34, 36

- 1 2 Wechsler (1979), pp. 158–159

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 33–34

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 36–37

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 37, 42

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 38–39

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 40–43

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 46–48

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 159 (n. 18)

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 44–45

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 45–46

- ↑ Graff (1992), pp. 48–49

- ↑ Graff (1992), p. 46

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), pp. 159–160

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 160

- ↑ Graff (2002), pp. 165–178

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), pp. 160–168

Sources

- Graff, David A. (1992). "The Battle of Huo-i" (PDF). Asia Major (Third Series) (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press) 5.1: 33–55. ISSN 0004-4482.

- Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300–900. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23955-9.

- Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "The founding of the T'ang dynasty: Kao-tsu (reign 618–26)". In Twitchett, Dennis. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–187. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Wright, Arthur F. (1979). "The Sui dynasty (581–617)". In Twitchett, Dennis. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–149. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||