Siege of Fort Pulaski

The Siege of Fort Pulaski (or the Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski) concluded with the Battle of Fort Pulaski fought April 10–11, 1862, during the American Civil War. Union forces on Tybee Island and naval operations conducted a 112-day siege, then captured the Confederate-held Fort Pulaski after a 30-hour bombardment. The siege and battle are important for innovative use of rifled guns which made existing coastal defenses obsolete. The Union initiated large scale amphibious operations under fire.

The fort's surrender strategically closed Savannah as a port. The Union extended its blockade and aids to navigation down the Atlantic coast, then redeployed most of its 10,000 troops. The Confederate army-navy defense blocked Federal advance for over three months, secured the city, and prevented any subsequent Union advance from seaward during the war. Coastal rail connections were extended to blockaded Charleston, South Carolina.

Fort Pulaski is located on Cockspur Island, Georgia, near the mouth of the Savannah River. The fort commanded seaward approaches to the City of Savannah. It was commercially and industrially important as a cotton exporting port, railroad center and the largest manufacturing center in the state, including a state arsenal and private shipyards.[8] Two southerly estuaries led to the Savannah River behind the fort. Immediately east of Pulaski, and in sight of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, lay Tybee Island with a lighthouse station.

Background

Fort Pulaski was built as a "Third System" fort in the United States system of coastal defense on land ceded to the United States by the State of Georgia. Authorized by appropriations begun by Congress under the James Madison administration, construction of Third System forts was directed under U.S. Secretaries of War including James Monroe of Virginia, William H. Crawford of Georgia, and John Calhoun of South Carolina.

The new construction replaced two earlier forts on Tybee Island. A British colonial fort was torn down in the American Revolution. The first U.S. fort, authorized in the Washington Administration, was swept away in an 1804 hurricane. Construction began on Fort Pulaski during 1830, and was completed in 1845 in the administration of John Tyler by a successor of U.S. Secretary of War John Bell of Tennessee. The new fort was named to honor Casimir Pulaski, the Polish hero of the American Revolution.[9] A young Lieutenant Robert E. Lee served as an engineer during the construction of the fort, at which time he resided in Savannah, Georgia.

|

The Third System fort expanded Savannah's defenses downriver from "Old" Fort Jackson, a "Second System" fort which had been built nearby the city to defend the immediate approaches to its wharves. In the campaigns for national elections in 1860, Southern secessionists threatened civil war, were their opponent to be elected President. Following the policy of President James Buchanan and his Secretary of War John B. Floyd of Virginia, the newly inaugurated Lincoln Administration at first did not garrison and defend forts, arsenals or U.S. Treasury Mints in the South. The policy was continued until April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, just north along the Atlantic Coast from Fort Pulaski.

"Department of Georgia"

-

Fort plan shows outline and features, demilune

-

Southeast parapet, south wall barbette guns

-

8-in. gun as a mortar held Union to night movement

-

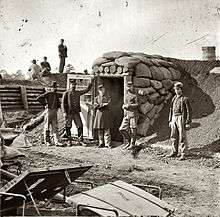

Bombproofs of timbers, yard trenched for ricochets

On January 3, 1861, sixteen days before the secession of Georgia from the Union, volunteer militia seized Fort Pulaski from the Federal government[10] and, with Confederate forces, began repairing and upgrading the armament. In late 1861, the commander, Department of Georgia, General Alexander Robert Lawton would transfer to Richmond. On November 5, General Robert E. Lee assumed command of the newly created "Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida".

Lawton's October report for his Department listed 2,753 men and officers in the environs of Savannah, almost half of the command.[11] First Georgia Regulars had been assigned to Tybee Island. They built a battery on Tybee Island and manned it, along with lookouts along the beach.[12] The Regiment was reassigned to Virginia, departing July 17, 1861.[13] Olmstead’s “First Volunteer Regiment of Georgia”[14] would garrison Fort Pulaski through the Federal siege.[15]

Fort Pulaski was considered invincible with its 7-1/2-foot solid brick walls and reinforcing masonry piers. General Robert E. Lee had earlier surveyed the fort’s defenses with Colonel Olmstead and determined, “they will make it pretty warm for you here with shells, but they cannot breach your walls at that distance." Wide swampy marshes surrounded the fort on all sides and were infested with native alligators. No attacking ship could safely come within effective range, and land batteries could not be placed closer than Tybee Island, one to two miles away.[16] Beyond 700 yards, smoothbore guns and mortars had little chance to break through heavy masonry walls. Beyond 1,000 yards, they had no chance at all. The U.S. Chief of Engineers, General Joseph Gilbert Totten, is quoted as saying, "you might as well bombard the Rocky Mountains."[17] If there were ever to be a successful siege, it would have to starve the garrison into submission.[18]

Fort garrison duty with untrained troops made up for lost time. In May for example, one newspaper correspondent reported that Confederates spent early morning in heavy labor such as mounting heavy guns. Then came an hour and a half drill at the heavy guns with instruction or live fire out a mile or two. The proficiency of each gun crew was tracked in a “target practice” book. Troops were tested on gunnery skills, then dinner at one. The rotating fatigue parties returned to work Officers reviewed infantry tactics, then instructed the men for an hour. Fatigue parties had “recall” at six. Then at “Dress Parade” retreat, the garrison performed infantry drill including combat formation evolutions. Supper followed and afterwards an hour’s recitation of army regulations, taps at nine.[19]

Operationally, General Robert E. Lee headquartered in Savannah as commander of the “Department of the Coast of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida”. He was returning to the fort that he had helped construct in his early U.S. career. He had been instrumental in the engineering connected with channelling tidewaters around the fort where a hurricane had swept a previous structure on the same site. He knew the lay of the land and the tides of the sea there.

Defense in depth

When Federal forces first made a lodgment on Tybee Island, the work on Fort Pulaski was progressing slowly, but Robert E. Lee’s judgment as the District's commanding general was that “the river cannot be forced”.[20] Old Fort Jackson had been armed, strengthened and “forms an interior barrier”. Savannah’s channel had been blocked. In December, Lee reasoned since the Federals had sunk a Stone Fleet in the Charleston Harbor, they did not intend to use it. “We must endeavor to be prepared against assaults elsewhere on the Southern coast.” To that end, additional ships were sunk by Confederates in water approaches that led behind Fort Pulaski.[21]

Lee brought Commodore Tattnall from a James River command, where under imminent attack from Union monitors he had landed sailors to expand Richmond fortifications immediately after the Battle of Hampton Roads. Tattnall then manned batteries with his gunners to repel monitor attacks threatening to bombard Richmond's Tredegar Iron Works. Tattnall's sailors would perform similar service at a battery across from Savannah's Fort Jackson. Turning his attention to Fort Pulaski's defenses, Lee anticipated Union moves to establish batteries above the Fort. He ordered guns positioned to cover their likely positions were the Federals to get behind Pulaski in a siege attempt.[23]

In January, following Tattnall’s three-gunboat attack on seven Federal gunboats on the river, Lee’s assessment was that “there is nothing to prevent their reaching the Savannah River, and we have nothing afloat that can contend against them." Fort Pulaski, a “Third System”, scientifically engineered coastal defense fort, still had at least four months’ provisions. Now, the primary objective became, “we must endeavor to defend the city.” The city’s floating dock was sunk as another river obstruction.[24]

In March, Lee passed along War Department orders to begin transferring regiments from Florida to Tennessee to reinstate operations following the “disasters to our arms” there. Georgian troops had been sent to Virginia in July, additional Georgians would be moved to Tennessee also. The Confederate government required a withdrawal from seaboard forces into the interior of South Carolina and Georgia to better secure the breadbasket plantations feeding the armies. In Florida, only the Apalachicola River had to be defended at all costs because Federal gunboats could penetrate so deeply into the Georgia interior.[25]

On Lee’s transfer to Richmond, he detailed urgent defense construction, then he called on Lawton’s “earnest and close attention” to the Federal’s probable approach to the city. “It looks now as if he would take the Savannah River”. Guns located in island batteries were to be removed to the mainland in and around Savannah’s defensive lines. Obstructions in the river above the city were to be set by hands provided by upriver planters in the event of an envelopment by way of Fort McAllister. “Every effort must be made” to retard or prevent further progress of the enemy directly upriver on the Savannah River approaches. “If he attempts to advance by batteries on the marshes or islands, he must be driven back, if possible.” Scouts were ordered out “so as to discover his first lodgment, when they can be broken up.” An additional three-gun battery at MacKay’s Point was not intended to stop federal gunboats in force, but with Tattnall’s gunboat support, they could prevent Federal batteries from being built on Elba Island to threaten Old Fort Jackson.[26]

Savannah's existing Fort Jackson, about three miles downriver from the city, was supplemented with two additional batteries. Defenders built fire barges.[27] Lee first placed a battery at Causton’s Bluff commanding navigable estuaries leading to the Savannah River behind Fort Pulaski. Then he added another battery situated farther upriver on Elba Island, blocking all river approach to Savannah. The Union naval commander, Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont, conducted a reconnaissance of Lee's system of defense upriver. When the commanding military general, Gen. Thomas W. Sherman, insisted on forcing Lee's riverine batteries against Du Pont's recommendation, Thomas Sherman was transferred to the western theater and replaced by General David Hunter.

The Union fleet conducted explorations among the Atlantic inlets and coastal marshes by shallow draft ships, boats and monitors.[28] But when they came up against earthworks such as Fort McAllister just south of Savannah, their efforts using bombardment alone were fruitless.[29] The Federals would not advance on Savannah until General William T. Sherman’s March from the interior in 1864.[30]

At the time Pulaski was cut off from Savannah in April 1862, the garrison under the command of Colonel Charles H. Olmstead had been reduced from 650 to 385 officers and men. They were organized into five infantry companies and had 48 cannons, including ten columbiads, five mortars, and a 4.5-inch (110 mm) Blakely rifle.[31] The Confederate Tybee Island battery had been previously dismantled and abandoned, and their guns relocated to the fort.[32] The fort had been provisioned on January 28 with a six-month supply of food.

In consultation with Lee, Olmstead had distributed armament on the ramparts and in the casements to cover all approaches, and several were placed to cover westerly marshes and Savannah’s North Channel.[32] Confederate marauders burned sea island cotton crops to deny them falling into Federal hands. Navigational aids like the Tybee Lighthouse were dismantled and burned. Reports from the field had Confederate troops setting fires to everything that might be used by advancing Federal troops.[33]

Federal advance

In August 1861 Secretary of War Cameron had authorized a combined “Expeditionary Corps” of Army and Navy. Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman commanded Army elements, and Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont commanded the Naval Services. The Union forces intended to recapture Fort Pulaski as federal property, to close the port of Savannah to the rebels, and to extend their blockade southward. First they needed a coaling station for the blockading South Atlantic Squadron. It then could serve as a base for the expedition. Fort Sumter would not be retaken until 1865, but the Battle of Port Royal answered the immediate requirement for a nearby staging area.[34]

Blockade

-

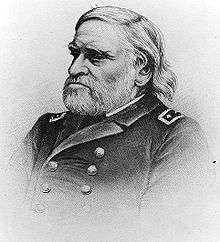

Samuel F. Du Pont, Union Flag Officer commanding

-

USS Wabash landed crew manning a Parrott cannon

-

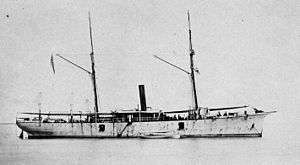

USS Unadilla, a gunboat in blockade of Savannah

As the Union forces went about taking Port Royal, Commodore Josiah Tattnall, CSN, and his “mosquito fleet” mounted an active defense, harassing elements of the Union’s South Atlantic Squadron. Over the next few months, Tattnall, an experienced US Navy commander, trained and fought his Confederate squadron into a flexible task force for coastal, amphibious, resupply and riverine operations. With the approach of the Federal expedition on Port Royal, including fifteen warships under the command of Flag Officer Du Pont, the Confederate “Savannah River Squadron” sortied with gunships CSS Savannah (flag), Sampson, Lady Davis and tender Resolute. These four along with the converted slaver-privateer Bonita,[35] met eight of Du Pont’s fifteen US warships on November 5, and were “outgunned and outclassed”.[36]

They withdrew overnight into Skull Creek, Georgia. The next day they sortied again. Under covering fires from Old Savannah engaging nearby heavy Union ships, the Sampson[37] assisted in amphibious operations taking off numbers of the Port Royal garrison. Resolute, returning from delivering dispatches to the City of Savannah, evacuated the garrison at Fort Walker. She then landed at Pope’s Landing, Hilton Head Island, and spiked Confederate guns abandoned there.[38] The Savannah landed a shore party of Marines to support Fort Beauregard under fire from Union warships, but the fort was lost before the reinforcements could arrive. The ship took off the garrison and returned to Savannah for repairs.[39]

Contact

After building up facilities on Hilton Head Island, the Federals began preparations for besieging Fort Pulaski. The Union expedition next captured Tybee Island.[40]

The Union advance on Fort Pulaski began on November 24, 1861. Following reconnaissance that Confederates had abandoned Tybee Island, Flag Officer Du Pont ordered forward an amphibious raid with three gunboats at the Tybee Island Lighthouse.[42] Under a two-hour ship’s bombardment, the Confederate pickets set fire to the lighthouse and withdrew.[43] Commander Christopher Rodgers, USS Flag, led a landing party of sailors and Marines in thirteen surf-boats to occupy the Lighthouse and the Martello tower, and flew the national flag from them. Overnight, a reduced company set false campfires to misdirect the Confederates ashore.[44][45] Two days later commanding Flag Officer Du Pont and General Thomas Sherman made a personal reconnaissance,[15] and on 29 November, General Gillmore, the command’s chief engineering officer, with three companies of the Fourth New Hampshire, took formal possession of the entire island without opposition.[46] The Navy set the logistics train in motion, and by December 20, the Army had sufficient materials for establishing “a permanent possession”.[47]

The last blockade runner to make Savannah was the British steam ship Fingal. Its cargo of arms and munitions reached the entrance to Wassaw Sound at the mouth of the Savannah River on a clear night in mid November, but heavy fog in the early morning masked the ship’s progress across the bar and upriver. Later she made two unsuccessful attempts at escaping the blockade before being converted into an ironclad.[48] Pulaski’s share on ship's manifest was two 24-pounder Blakely rifles and a large consignment of British-made Enfield infantry rifles. As the Union Flag Officer Du Pont sought to close the alternative channels local ships used, he sank stone-filled ships in the Savannah River channel, and stationed gunboats at two southerly estuaries, Wassaw Sound, south of Wilmington Island, and Ossabaw Sound at Skidaway Island.[32]

On November 26 Tattnall’s flag, CSS "Old" Savannah, in company with Resolute and Sampson sortied out from under Fort Pulaski’s guns in a “brave but brief” attack on the Union ships outside the bar, driving them out to sea. Tattnall’s squadron withdrew up the Savannah River for refit and two days later, the same three resupplied the Fort with six months provisions, despite “the spirited opposition of Federal ships”. "Old Savannah was partially disabled but returned to harbor. Sampson received considerable damage, returning to patrol the Savannah River only in mid-November the following year.[49]

Siege

besieging batteries upriver had infantry and gunboat support to cut off Pulaski from Savannah

The U.S. siege plan would make military history. Quincy Adams Gillmore was General Thomas Sherman’s chief engineering officer. His professional reading had followed the test records of the experimental rifled gun which the Army had begun testing in 1859.

Following a reconnaissance of the ground, he proposed the unconventional plan to reduce Fort Pulaski with mortars and rifled guns.[50] Commanding General Thomas W. Sherman[51] approved the plan, but not the promise of the rifled guns. His endorsement was qualified, believing gunnery effect would be limited, "to shake the walls in a random manner." But the innovative weaponry in the event made his deployed 10,000-man assault force unnecessary.[17] Of the two senior military commanders leading up to the engagement, neither Union General Thomas Sherman, nor Confederate General Robert E. Lee believed the fort could be captured by bombardment alone.

Approaches

Two sites for Federal batteries were selected upriver from the fort to cut it off from Savannah, just as Lee had anticipated. The first was at Point Venus at the east end of Jones Island along the north bank of the Savannah River North Channel. Confederate Commodore Josiah Tattnall had sunk a stone schooner to obstruct the northward channel connecting the river to the Union-held Port Royal, and he patrolled the river with Confederate gunboats. The Federals had to clear the obstruction on their most direct supply line first; it required three weeks. A camp and supply depot was established on the next island north, Dawfuskie Island.[52]

.jpg)

Confederate Commodore

Tattnall’s gunboats still commanded the lower river around Point Venus. As a part of Lee's active defense, the Confederate's Savannah River Squadron launched continuous patrols. Their naval gunnery required the work along the river by Union besiegers to be done at night. The Federal's guns had to be pulled by hand through swamp over moveable tram sections, the men working in brackish alligator-infested marsh, sinking in over their waist most of the day. The artillery then had to be placed on board-and-bag platforms to avoid their loss by sinking into the morass. The soldiers rested during the day.[52]

By Lee's estimation, the fort could not be reduced by bombardment or direct assault, only by starvation. As long as supplies could be built up, they would be. The last Confederate supply ship to Fort Pulaski was the small workhorse steamboat Ida. On February 13, it was on a routine run to the fort down the North Channel. The new battery of Federal heavy guns on the north bank opened up for the first time. The old side-wheeler ran for Pulaski and the battery got off nine shots before the guns recoiled off their platforms. Union troops went back to work modifying platform construction and resetting the cannon. Two days later Ida ran up the South Channel under the extinguished lighthouse and returned to Savannah through Tybee Creek.[53]

Once the Union battery at Venus Point was disclosed, Confederate gunboats engaged in gunnery duels, but they were driven off.[52] Over the next week, the besiegers completely surrounded the Fort. Federals built another battery on the Savannah River across from Venus Point. They threw a boom across Tybee Creek and cut the telegraph line between Savannah and Cockspur Island. Two infantry companies entrenched nearby to ward off Confederate raiding activity and a gunboat was detailed to patrol the channel and support the infantry. By late February 1862, no supplies or reinforcements could get in; the Confederate garrison could not get out. The last link of communications was a weekly swamp swimming courier.[53]

At the end of February Tattnall laid plans for an amphibious assault on the two advanced batteries at Venus Point and Oakley Island. General Lee personally interceded. Preparations at Old Fort Jackson were not completed. Although Tattnall's flagship had been put back into service since the Squadron's January resupply sortie, one of the three gunboats was still seriously disabled. Lee reasoned that if Tattnall's plan failed, the city itself would be open to attack. The three-to-seven exchange had not gone well for the defenders of Savannah. A possible two-to-seven match against ships with superior armament did not promise better. No further consideration was given to relief of the Fort; in any case, it had perhaps sixteen weeks of provisions left in store. Meanwhile, Federal emplacements continued to improve on Jones and Bird islands, Venus Point and other points along the river.[54] During the Federal bombardment of Fort Pulaski, April 10–11, “Old Savannah” participated in counter-battery fire with besieging Union guns.[55]

like those built on Tybee Island

Heavy caliber rifled cannon which the Federals needed to reduce Pulaski had arrived nearby in February, at which time Gillmore decided to locate the batteries at the northwestern tip of Tybee Island nearest the fort.[40] By March, Gillmore was offloading siege materiel onto Tybee Island. Roads had to be laid down, gun emplacements excavated, magazines and bomb-proofs constructed. As the work progressed southwesterly nearing the Fort, in the last mile the Union troops came under fire from the Fort’s Confederate gunners. A ranging shot said to be aimed by Colonel Olmstead himself cut a Union soldier in two. The following bombardment from elevated fort guns effected mortar barrages that forced all construction to proceed on Tybee Island by night. Each morning the uncompleted elements of siege construction were camouflaged against the fort's spotters.[56]

To land the cannon onto Tybee Island, artillery pieces were taken off transports, set on rafts at high tide, and pitched into the surf near shore. At low tide, manpower alone would drag the guns up the beach. Two hundred and fifty men were required to move a 13-inch mortar along on a sling cart. Later Union amphibious operations would employ contraband labor for much of this work.[57] Along the two-and-a-half mile front, their engineers had to construct almost a mile of corduroy road made of bundles of brushwood to keep the guns from sinking into the swamp. While offloading proceeded day and night according to the tides, Confederate bombardment from Fort Pulaski gunners required all Federal movement into the island limited to night time.[58] After a month of work, 36 mortars, heavy guns and rifled cannon were in position.[40]

One of the two 13-inch mortars of Battery Halleck at 2400 yards range was given the task of signaling the opening of the bombardment. The battery would proceed by shelling the arches of the north and northeast faces with plunging fire, "exploding after striking, not before".[59]

The four batteries closest to the fort were each given specific firing missions. Battery McClellan at a range of 1650 yards with two 84-pounder and two 64-pounder James rifled cannon (old 42 and 32 pounders, rifled), was to breach the pancoupé between the south and southeast faces and the adjacent embrasure. (A pancoupè is a blunted point of a multi-faced fortification.) Battery Sigel at 1670 yards included the five 30-pounder Parrotts and a 48-pounder James rifled cannon (formerly a 24-pounder smoothbore.) Their mission was to fire on the barbette guns until silenced, then switch to percussion shells onto the southeast walls and adjacent embrasure, at a rate of 10–12 rounds an hour to effect wall penetrations for the planned infantry assaults to come later. Battery Totten at a range of 1650 yards with four 10-inch siege mortars was assigned to explode shells over the northeast and southeast walls, or at any hidden batteries outside the fort. Battery Scott at 1740 yards with its three 10-inch and one 8-inch Columbiads was to fire solid shot and breach the same area as Battery McClellan. [60]

Fire was to cease at dark, except for special directions, and in the event, intermittent harassment was sustained on the fort overnight. A signal officer was stationed at Battery Scott to communicate the ranging of the mortar batteries Stanton, Grant and Sherman.[61]

Bombardment

Following prohibitive rain squalls on the ninth, all was ready for the Federals by April 10, and the newly appointed Commander of the Department, Major-General David Hunter, sent a demand for “immediate surrender and restoration of Fort Pulaski to the authority and possession of the United States.” Colonel Olmstead replied, “I am here to defend the fort, not to surrender it.”[62] The bombardment began at 8:00 a.m., concentrating on the fort's southeast corner which suffered greatly. The Confederate gunnery was described by the Federal commander as “efficient and accurate firing ... great precision, not only at our batteries, but even at the individual persons passing between them.”[63]

As the day wore on, counter-battery fires from Fort Pulaski were gradually silenced as their guns were either dismounted or rendered unserviceable.[17] Two of the Federal 10-inch columbiads jumped backwards off their carriages. The 13-inch mortars placed less than 10% rounds on target.[64] But Federal fires proved effective from Parrott's, James rifles, and working columbiad guns. There ensued a lull from the Fort, but the Confederate gunners re-opened an energetic counter battery duel that required the Parrotts to give up their wall assignment and concentrate on the working Confederate guns until they were re-silenced. By nightfall the wall at the southeast corner had been breached.[52] Under periodic harassing bombardment throughout the hours of darkness, Olmstead's garrison put several guns back into service.

Overnight, Du Pont’s flagship USS Wabash detached 100 crew to man four of the 30-pounder Parrott rifles.[65] In the morning, with the wind picking up right to left and affecting shell projectory,[66] the Union artillery resumed the bombardment, concentrating fires to enlarge the opening. The Georgia gunners again found targets, described in dispatches as Rebel “firing ... good all the morning, doing some damage”. At the same time, the Parrott rifles and Columbiads opened a great gap in the wall, sending shot across the interior of the fort and against the northwest powder magazine containing twenty tons of powder. Regarding his situation as hopeless, Olmstead surrendered the fort at 2:30 p.m. that day.[17]

General Gillmore reported in his after-action assessment of the siege by his artillery, “Good rifled guns, properly served can breach rapidly” at 1600–2000 yards when they are followed by heavy round shot to knock down loosened masonry. The 84-pounder James is unexcelled in breaching, but its grooves must be kept clean.[67] The 13-inch mortars had little effect.[52] The new 30-pounder Parrott Rifle had made a major impact on the battle. The rifled cannon fired significantly further with more accuracy and greater destructive impact than the smoothbores then in use. Its application achieved tactical surprise unanticipated by senior commanders of either side.[17]

Aftermath

Military fallout

- Union: The port of Savannah was closed to the Confederacy early, extending the Union blockade. Damage to the fort was repaired in six weeks, and the Confederates made no attempt to retake it.[17] Heavy rifled cannon made masonry fortifications obsolete, revolutionizing coastal defense as much as the Battle of the Monitor and Merrimac had for warships.[17] The City of Savannah itself remained in Confederate hands until the arrival of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman in December 1864, Sherman's March to the Sea.[17]

- “Lessons learned” by the Union were not immediately adopted. In its December 1864 attack on Fort Fisher, the bombardment was diffused and scattered, without any real damage to the fort by the many shots aimed at the fort’s flagpole. Admiral Porter adopted General Gillmore’s gunnery tactics for the second attack, assigning targets until they were destroyed. The January 1865 bombardment dismounted 73 of the fort’s 75 guns and mostly shot away the fort's palisade.[68]

- Confederate: Commodore Josiah Tattnall's efforts to break the Union blockade at Savannah extended the modern era armored warships with ironclads CSS Atlanta (1862) and CSS Savannah (1863).[69] To elaborate Savannah’s defenses, a torpedo station was established[70] under military command. The ironclad USS Montauk survived the detonation of a torpedo while attacking Fort McAllister in 1863.[71] Given shortages in marine engines, the Confederate Navy built floating battery CSS Georgia (1863). Closure of gaps and connections between railways in Savannah, Augusta, and Charleston allowed timely movement of troops and supplies to besieged Charleston from late 1862 through 1864.[72]

- "Lessons learned" by the Confederates were immediately incorporated into the defenses of Charleston, SC. On his release as a prisoner-of-war, Colonel Olmstead was assigned engineer and gunnery duty there. Repeated Union naval and amphibious assaults failed 1862–1865, both Union gunboats and ironclads repeatedly suffered substantial damage and loss by Confederate gunnery and mines.[73]

Men of war

- Union: Gen. David Hunter, issued his General Order Number Eleven on May 9, 1862 that all slaves in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina were free. President Lincoln quickly rescinded it, reserving this "supposed power" to his own discretion if it were indispensable to saving the Union. Abolition was to be outside the police functions of field commanders.[74] Nevertheless, Pulaski became a terminal on the Underground Railroad, initiating freedman education and supplying many of 517 African-American Georgians serving in the US Navy 1862–1865.[75]

- Confederate: In late 1864, 520 Confederate officer prisoners were transferred to Fort Pulaski. The fort‘s commander, Col. Philip P. Brown, Jr., attempted to restore full food rations upon arrival, but was ordered not to by the district commander who put the men on starvation rations on December 15. After district command changed, a medical inspection on January 27, 1865 resulted in the restoration of normal rations. As many as 55 men died before they were sent to Fort Delaware in March 1865. These prisoners were the Confederacy's “Immortal Six Hundred”.[76]

Access today

See the "External Links" section below "References" to find directions, hours of operation, and descriptions of exhibits.

- Fort Pulaski, is located at on a barrier island near Savannah, Georgia. It is open to the public today as the Fort Pulaski National Monument and museum. It is a "Third System" fort in the U.S. system of coastal defense. The "scientifically designed" fort construction was supervised by Robert E. Lee and the Fort's 112- day defense in depth was put in place under his command. Construction of Third System forts was directed under Secretaries of War William H. Crawford of Georgia, and John Calhoun of South Carolina.

- Old Fort (James) Jackson, is located in the City of Savannah. It is a "Second System" fort and museum, including American Revolution, War of 1812, and Civil War history. The Second System of forts was begun under the administration of Thomas Jefferson. It is maintained by the Coastal Heritage Society.

- Fort McAllister, a Confederate earthenworks that defeated Union Monitor attacks six times, is preserved as the Fort McAllister Historic Park, a Georgia State Park located just south of Savannah. It was begun under President Jefferson Davis, with Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin of South Carolina.

-

Today's wall[1]

-

Wall that was breached and repaired with moat around the fort

-

Drawbridge over the moat

-

View from the Fort Pulaski National Monument

-

Plaque at Fort Pulaski

- ^ Restored Fort Pulaski on view at Fort Pulaski National Monument, Savannah, GA

References

- ↑ Fort Pulaski under fire April 10–12, 1862. Viewed from northeast, North Channel, Savannah River. Union batteries bombard from Tybee Island. Brick thrown into the air is off the southeast corner of the fort by new Parrott Rifle cannon using percussion projectiles, making 7-foot penetrations.. (Leslie's Weekly Magazine)

- ↑ CSS Georgia: Archival Study Swanson, Mark and Robert Holcombe. January 31, 2007, p.30

- ↑ New York Times, 04/20/1862 “Other official documents”. Fort Pulaski surrender.

- ↑ Gillmore, p. 62

- ↑ CSS Georgia: Archival Study Swanson, Mark and Robert Holcombe. Jan 31, 2007, p.30. On March 30, 1861, the vessels and crews of the Navy of Georgia were turned over to confederate authorities

- ↑ Swanson, M. and Holcombe, R., op.cit. p.30

- ↑ Jones, Charles C., Jr., chief of artillery of the Confederate Department of Georgia “Seizure and reduction of fort Pulaski” article in “The Magazine of American history with notes and queries, Volume 14”, 1885 edited by John Austin Stevens, et al. p. 56. Fort 48 guns of all calibers: five 10-inch and nine 8-inch columbiads unchambered, three 42-pounder and twenty 32-pounder guns, two 24-Blakely rifle guns, one 24-pounder iron howitzer, two 12-pounder bronze howitzers, two 12-inch iron mortars, three 10-inch sea-coast mortars, and one 6-pounder bronze field piece.

- ↑ Savannah boasted a roundhouse repair facility. Three railroads at the time of the Civil War were (1) Central of Georgia Railroad, 1843, to cotton center of the state: Macon and Milledgeville; (2) Savannah, Albany and Gulf Railroad to the south central part of Georgia; and (3) the Savannah Charleston Railroad in 1860 (later the "Charleston Savannah Railway"). The value of 38 manufacturing establishments of all kinds totaled near $1 million, more than any other county in the state. CSS Georgia: Archival Study Swanson, Mark and Robert Holcombe. January 31, 2007, p.13

- ↑ National Park Service. General History of Fort Pulaski. Viewed 11/10/2011.

- ↑ Pryor, Dayton E. (2009). The Beginning and the End: The Civil War Story of Federal Surrenders Before Ft. Sumter and Confederate Surrenders after Appomattox. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7884-2007-8.

- ↑ Official Records, Army, excerpts. 379 men and officers were assigned to Fort Pulaski, another 1,183 on Tybee Island, 658 on Skidaway Island, and 533 in Savannah’s camps.

- ↑ Archaeological Reconnaissance at the Drudi Tract, Tybee Island, Chatham County, Georgia. LAMAR Institute Publication Series, 127, By Daniel T. Elliott., Savannah, Georgia, 2008, p.14. Troops under the command of William Duncan Smith. Col. Olmstead would later command this regiment in the Army of Tennessee after service with his volunteers in the defense of Charleston, 1863.

- ↑ On orders to proceed to Virginia by the Confederate government, General Lawson directed the 1st Georgia Regulars to make transit regardless of protests from the Governor of Georgia. Two 8-inch columbiads from their Tybee Island battery were dismounted and relocated into Fort Pulaski.

- ↑ The pre-Civil War militia designation was used by the unit, officially Georgia’s Ninth Volunteer Regiment.

- 1 2 Elliott, op.cit.

- ↑ Lattimore, Ralston B., “Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia, Historical Handbook Number Eighteen 1954 (reprint 1961).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lattimore, Ralston B., op.cit.

- ↑

- Jones, Charles C. , Jr., “Military lessons inculcated on the Coast of Georgia during the Confederate War” an address before the Confederate survivors’ association, Augusta Georgia, April 26, 1883. by Col. Charles C. Jones, Jr., pres. of the association.

- ↑ DAILY CONSTITUTIONALIST, Augusta, GA, May 17, 1861, p. 2, c. 1. The newspaper’s anonymous correspondent at Fort Pulaski was signed “Novissimus”, possibly an officer in the First Georgia Regulars

- ↑ Lee’s strategic considerations are outlined in his official correspondence as commanding officer of the department from Savannah on November 29 and December 20 to Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin, January 29, to General Samuel Cooper, March 1 to General Gen. James H. Trapier, and March 3 to General Alexander Lawton.

- ↑ Official Records, Armies, Chapter XV. Operations on the Coasts of South Carolina, Georgia and middle and east Florida. August 21, 1861 – April 11, 1862. Correspondence, etc. – Confederate. November 29 on p. 32, December 20 on p. 42.

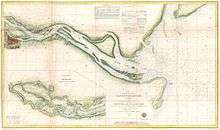

- ↑ 1855 Navigation Chart. City of Savannah (red, left edge). "Old Fort Jackson" (red, center) at the river bend.

Fort Pulaski (red, right) on Cockspur Island at river's mouth. North shore of Tybee Island is due east (lower right). The inset extends the map northeast up the coast towards Charleston, S.C. Map shows sailing directions: piloting offshore, finding anchorage, beating over the bar, tides, currents, navigational aides. Click once to the Wikimedia site. Click again for map full screen, click again for magnification to read notes. - ↑ Fort Pulaski – National Monument], National Park Service Historical Handbook Series, “General Lee Returns to Fort Pulaski” (1961).

- ↑ Official Records, Armies, op.cit. Chap. XV. p. 85, January 29, 1862

- ↑ Official Records, Armies, op.cit. Chap. XV. March 1, 1862. p. 403

- ↑ Official Records, Armies, op.cit. Chap. XV. March 3, 1862, p. 34

- ↑ CSS Georgia: Archival Study Swanson, Mark and Robert Holcombe. January 31, 2007, p.25

- ↑ Porter, David D., “The Naval History of the Civil War” Chapter 9, operations of Admiral Du Pont’s squadron in the sounds of South Carolina. page 83+.

- ↑ “Fort McAllister I” National Park Service (nps), Heritage Preservation Services, The American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP).

- ↑ http://shapiro.anthro.uga.edu/Lamar/images/PDFs/publication_127.pdf | Archaeological Reconnaissance at the Drudi Tract, Tybee Island, Chatham County, Georgia. LAMAR Institute Publication Series, #127, By Daniel T. Elliott., Savannah, Georgia, 2008, p.14

- ↑ Brown, David A. "Fort Pulaski: April 1862." The Civil War Battlefield Guide: Second Edition. Edited by Frances H. Kennedy. Goughton Mifflin Company, New York, 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6

- 1 2 3 Fort Pulaski – National Monument, Historical Handbook, NPS, Op. Cit. “Investment of Fort Pulaski”

- ↑ Elliott, 2008, p. 153.

- ↑ National Park Service battle description

- ↑ History of the Confederate States navy”, Scharf, John, p. 89. The brig Bonita (also “Bonito”), built in New York in 1853, 276 tons burden. A fast sailer. Formerly engaged in the slave trade, captured on the coast of Africa, taken to Charleston, then Savannah, where she was seized and converted into a Georgia privateer.

- ↑ Swanson, M. and Holcombe, R., op.cit. p. 30. Minimal losses were suffered on either side.

- ↑ The CSS Sampson, also Samson. The sidewheeler steamboat had been a tugboat prior to purchase by the Confederate Government, 1861.

- ↑ “Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Navy Dept., Naval Historical Center, online at CSS Savannah, CSS Sampson, CSS Lady Davis, Resolute, CSS Ida, CSS Georgia: Archival Study Swanson, Mark and Robert Holcombe. January 31, 2007, p.30

- ↑ Jones, Charles C., Jr. The life and services of Commodore Josiah Tattnall 1878. Morning News steam printing house, Savannah.

- 1 2 3 NPS battle description, op.cit.

- ↑ Blockade Runner 1861–1865 By Angus Konstam. Sketch with description, p.9. History of the Confederate states navy, Scharf, J. Thomas, 1887. Fingal could not get out, later was converted to an Ironclad

- ↑ Elliott, op.cit. p.9. They were USS Flag, USS Seneca and USS Pocahontas.

- ↑ Elliott, Daniel, Archaeological Reconnaissance at the Drudi Tract, Tybee Island ... op.cit. p. 14. After early misleadingly optimistic reports, within a few days, Federal reports described the firing as having caused substantial internal damage to the lighthouse, and the lens appeared to have been removed by the evacuating Confederates sometime earlier.

- ↑ Marines in the Civil War, excerpts. Sullivan, David.

- ↑ Elliot, op.cit.

- ↑ Elliott, op.cit.p.10

- ↑ Victor, Orville James., The history, civil, political and military of the Southern Rebellion.... ISBN 978-1-149-22724-4 The publishers copyright is dated 1861, the preface for volume 2 is dated 1863. Viewed October 27, 2014.

- ↑ CSS Atlanta, USS Atlanta. Navy Heritage Following her successful blockade run into Savannah, ownership was transferred to the Confederate government as pre-arranged. Fingal was converted into a casemate ironclad and renamed CSS Atlanta (1862–1863). In her first attack on Union blockaders, she was blocked by obstructions. In the second in spring 1863, Atlanta was met by U.S. monitors Nahant and Weehawken, overwhelmed in a gunnery duel and surrendered. In early 1864, the ship was re-commissioned the USS Atlanta and took up station in the James River supporting Grant’s siege of Richmond.

- ↑ “Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Navy Dept., Naval Historical Center, online at CSS Savannah, CSS Sampson, CSS Lady Davis, Resolute, CSS Ida, "CSS Georgia: Archival Study" Swanson, Mark and Robert Holcombe. January 31, 2007, p.30

- ↑ Fort Pulaski – National Monument, Historical Handbook, NPS, Op. Cit. “The New Weapon”

- ↑ “Battles and leaders of the civil war”, vol.1, p. 691, cites Major General Thomas W. Sherman as senior commander, land forces. Succeeded by Major General David Butler, at the time of the April bombardment. See “Official records of the Union and Confederate armies”, Chapter XV, p. 135. Cornell University.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Victor, op. cit. p.106

- 1 2 Fort Pulaski – National Monument, Historical Handbook, NPS, Op. Cit.

- ↑ For a contemporary narrative of the process, see “chapter V... building batteries on Jones and Bird Islands” in Captain (later Colonel) James M. Nichols memoir, “Perry’s Saints, or the fighting parson’s regiment in the War of Rebellion”. 1886. the 48th New York State Volunteers regimental history from survivor interviews and soldier journals under the command of Methodist minister, Colonel James H. Perry. This regiment would later garrison Fort Pulaski. One of the earliest photographs of baseball is of this regiment playing in the fort yard. See the NPS website photos.

- ↑ CSS Georgia: Archival Study Swanson, Mark and Holcombe, Robert. January 31, 2007, p.27, “Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Navy Dept. , Naval Historical Center, online at CSS Savannah

- ↑ Fort Pulaski – National Monument, Historical Handbook, NPS, Op. Cit. “Gillmore sets the stage”

- ↑ This early in the conflict, it was still a “white man’s war”, and contrabands/freedmen were not yet employed under considerations for slave-holder ‘property’. Victor, op.cit., p.107.

- ↑ Victor, op.cit., p.106.

- ↑ Gillmore, Q.A. pp.28

- ↑ Gillmore, Q.A. pp.29-32

- ↑ Gillmore, Q.A. pp. 32

- ↑ Victor, op. cit., p. 107.

- ↑ Victor, op. cit. p.108

- ↑ Gillmore, Q. A., Official report ... of the siege and reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, March and April, 1862. by Brig.-Gen. Q.A. Gillmore, Captain of Engineers, U.S.A., to the United States Engineer Department, 1862, D.Van Nostrand, NY. The columbiads failed due to incompatible bolts shearing off. They were not inspected before they were placed in the line for firing.

- ↑ "Fort Pulaski National Monument, National Park Service Historical Handbook Series (1961). “Significance of the Siege”

- ↑ Gillmore, Q. A., Op.Cit, 1862, Appendix Tables of battery and gun fire.

- ↑ Gillmore’s orders had specified James guns having grooves cleaned every 5–6 rounds fired. NYT, op.cit.

- ↑ Anderson, Bern. “By Sea and by River: the naval history of the Civil War” 1962. Reprinted unabridged 1989 Da Capo paperback. ISBN 0-306-80367-4. p. 279-284. Admiral David D. Porter assumed command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron on 1 October 1864 to assemble fleet (p.278). On December 24–25, at rates of fire at times of 115 shells per minute, 20,000 shells amounting to more than 600 tons, the naval bombardment did little damage, killed three and 61 wounded. General Butler made no attack, but withdrew, resulting in his relief and court martial. (p. 280-281). In the January bombardment, Porter ranged four ironclads about 700 yards from the fort, with an additional 44 ships’ bombardment with specific targets assigned for each ship. While the Confederates were repelling the landing party assault, General A. J. Terry secured two fort guns before his attack was discovered. Porter and Terry conducted the “best coordinated amphibious assault of the war” against the “most formidable position taken”. The scholar Admiral Bern Anderson mentions these were the successful naval gunnery tactics used in World War II in battles such as the Bombardment of Cherbourg.

- ↑ CSS Atlanta, USS Atlanta. Navy Heritage The Fingal was converted to the ironclad CSS Atlanta. It made two sorties, was captured, repaired, and returned to service as the ironclad USS Atlanta supporting Grant's Siege of Petersburg.

- ↑ Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury”, Maury, Richard Launcelot.1901.

- ↑ http://www.navyandmarine.org/ondeck/1862ConfTorpedoService.htm Confederate Torpedo Service By R. O. Crowley The Century / Volume 56, Issue 2, The Century Company, New York, June 1898)

- ↑ Black, Robert C. Railroads of the Confederacy, University of North Carolina Press, 1998, pp. 161-162 refer to the projects to close the gaps in this coastal network

- ↑ Anderson, Bern. “By Sea and by River: the naval history of the Civil War” 1962. Reprinted unabridged 1989 Da Capo paperback. ISBN 0-306-80367-4. p. 156-177.

- ↑ "Presidential Proclamation May 19, 1862", Abraham Lincoln.

- ↑ Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War by Jacqueline Jones , ISBN 978-1-4000-7816-5 Vintage Books, 2009 p. 152

- ↑ “Fort Pulaski “The immortal six-hundred” Confederate Gen. Samuel Jones initiated human shield tactics to save Confederate Fort Sumter. Union Gen. J.G. Jones retaliated. Senior commanders on both sides contributed to abuse of their prisoners.

External links

- Fort Pulaski Savannah, Georgia. National Park Service. School visits are generally free. See “For Teachers”. NPS Suggested reading

- Cockspur Island Light, Savannah, Georgia, Fort Pulaski National Park. Marks seaward approach to North Channel and South Channel, Savannah River.

- Tybee Island light station, Savannah, Georgia, active Coast Guard with museum. Third Lighthouse.

- “Old Fort Jackson”, Fort James Jackson, Savannah, Georgia. Coastal Heritage Society.

- CSS Georgia. Floating gun battery off Old Fort Jackson. Army Corps of Engineers.

- Ironclads and gunboats of the Savannah River Squadron. Squadron headquartered at Old Fort Jackson. Background for historical marker.

- Ships of the Sea Maritime Museum. Ships models for Atlantic trade, 1700s and 1800s. descriptive listing by Nautical Research Guild.

- The Historic Railroad Shops and roundtable, Savannah, Georgia

- Fort McAllister, Richmond Hill, Georgia State Park. “Our Georgia History” recounts engagements with Union blockade, four in 1862, four in 1863, blockade runners, Sherman in 1864.

- St. Simons Island Light, Brunswick, Georgia, active Coast Guard with museum.

Further reading

Archives

- Gillmore, Q. A., Official report ... of the siege and reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, March and April, 1862.

by Brig.-Gen. Q.A. Gillmore, Captain of Engineers, U.S.A., to the United States Engineer Department, 1862, D.Van Nostrand, NY. - A compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I, volume 12, Cornell University, Making of America.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, vol. 6 chap. 15, Operations on the Coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Middle and East Florida, Aug 21, 1861 – Apr 11, 1862. vol. 44, Vol. 14, Chap. 26. Government Printing Office. Cornell University, Making of America.

- Davis, George B., Leslie J. Perry, and Joseph W. Kirkley 1894 Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Originally published in 1891, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

- Dyer, Frederick Henry, compiler, 1979 A compendium of the War of the Rebellion, Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the ... Several States, the Army Registers, and Other ... Two Volumes. National Historical Society with the Press of Morningside Bookshop, Dayton, Ohio. Originally published in 1908.

- Schiller, Herbert M., Sumter is Avenged! The Siege & Reduction of Fort Pulaski. Shippenburg: The White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1995.

- Victor, Orville James., The history, civil, political and military of the Southern Rebellion.... ISBN 978-1-149-22724-4 The publishers copyright is dated 1861, the preface for volume 2 is dated 1863.

Memoirs and Biography

United States

- Gillmore, Quincy A. "The Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski" (1863) ISBN 0-939631-07-5

- Porter, David D., “The Naval History of the Civil War”

- Weddle, Kevin J., "Lincoln's Tragic Admiral: The Life of Samuel Francis Du Pont" Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press 2005. ISBN 978-0-8139-2332-1

Confederate States

- Jones, Charles C., Jr. The life and services of Commodore Josiah Tattnall 1878. Morning News steam printing house, Savannah.

- Jones, Charles C., Jr., “Military lessons inculcated on the Coast of Georgia during the Confederate War” an address before the Confederate survivors’ association, Augusta Georgia, April 26, 1883. by Col. Charles C. Jones, Jr., pres. of the association.

- Olmstead, Charles H., “The Memoirs of Charles H. Olmstead”. Hawes, Lillian, editor 1964 Collections of the Georgia Historical Society 14.

Monographs

- Jones, Jacqueline. “Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War” (2009) ISBN 1-4000-4293-3

- Schiller, Herbert M., “Sumter is avenged: the siege and reduction of Fort Pulaski”, 1995. White Mane Pub. ISBN 978-0-942597-86-8

- Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. Bluejackets and Contrabands: African Americans in the Union Navy, 2009. U of Ky Pr. ISBN 978-0-8131-2554-1

- Wilson, Harold S. “Confederate Industry: Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War” 2002, ISBN 1-57806-462-7

Curriculum

- Erickson, Ansley. "War for Freedom: African-American Experiences in the Era of the Civil War, a web-based curriculum.” National Park Service. Pdf file created 2007. “Best practices” lesson plan, site supports student handouts. Though omitting primary and secondary sources (scan is truncated), generally meets requirements of the US Department of Education “Teaching American History” grant and teacher’s National Board Certification.

Coordinates: 32°01′38″N 80°53′27″W / 32.02729°N 80.89096°W

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||