Battle of Chiatung

| Battle of Chiatung | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

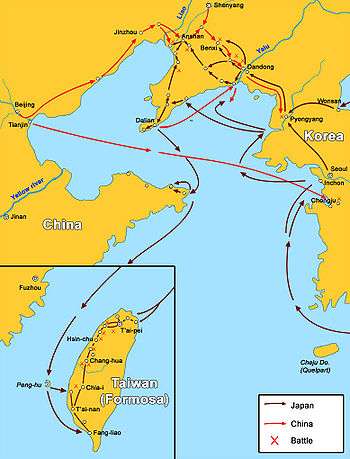

| Part of Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1895) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| two infantry companies | to be supplied | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 16 killed, 61 wounded | at least 70 killed | ||||||

The Battle of Chiatung (11 October 1895) was an important engagement fought during the Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1895). The battle was a Japanese victory.

The battle

The battle took place during the final phase of the campaign, in which the Japanese advanced on Tainan with three separated columns. Lieutenant-General Nogi's southern column, consisting of 6,330 soldiers, 1,600 military coolies and 2,500 horses, landed at Fangliao (枋寮) on 10 October 1895. The column engaged a force of Formosan militiamen at Ka-tong-ka (茄苳腳), modern Chiatung (佳冬), on 11 October. The battle was a Japanese victory, but the Japanese suffered their heaviest combat casualties of the campaign in the engagement—16 men killed and 61 wounded. Three officers were among the casualties.[1]

The following description of the battle was given by James W. Davidson:

Two companies of infantry were also sent along the beach road, but finding none of the enemy in that direction they marched towards Ka-tong-ka. On arriving near the village the next morning, they found it surrounded by a low stone wall loop-holed for rifle fire. Several cannon made the place quite a formidable stronghold, and, after the Japanese had surrounded the village, the stubborn resistance made by the Chinese showed that the latter intended to take full advantage of their position. A body of water, which nearly surrounded the village, greatly hindered the Japanese in attacking at close range, and the enemy were so well protected that it was only a waste of ammunition to fire from a distance. The Japanese made several futile charges with considerable loss of life before a battalion commander and one company succeeded in gaining an entrance through one of the gates, though not without loss, and set fire to some of the houses. A strong wind blowing in the right direction carried the flames quickly toward the Chinese, who were making a stout defence. Only one chance was now open to them—to come out into the open field and face the Japanese—but this they did not care to do. With the crackling of the bamboo, the falling of houses, the awful roaring of the fire as it swept nearer and nearer to the horror stricken braves, who were now joined by others driven out of the houses in which they had sought shelter, the scene became one of intense excitement. The cries of the Chinese could be heard above the uproar, and the poor wretches crouched closer and closer to the stone wall, taking advantage of pits or trees and bushes already smouldering, to protect themselves from the stifling heat of the conflagration. At last they could bear it no longer, and with a yell of terror they threw themselves over the wall and made a mad rush for the scrub and jungle to the north. Many fell by the way, but the majority made good their escape.

This affair was a serious one for the Japanese, who lost 77 men (16 killed and 61 wounded) including three officers—by far the greatest loss yet sustained by them in Formosa. Seventy bodies of Chinese were found, and probably a few others were consumed by the flames. Twelve cannon, several rifles and some ammunition fell into the hands of the Japanese. The Chinese taking part in this engagement were not Black Flags, but were composed wholly of native levies.[2]

Notes

References

- Davidson, J. W., The Island of Formosa, Past and Present (London, 1903)

- McAleavy, H., Black Flags in Vietnam: The Story of a Chinese Intervention (New York, 1968)

- Yosaburo Takekoshi, Japanese Rule in Formosa (London, 1907)

| ||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)