Battle of Ban Me Thuot

| Battle of Ban Me Thuot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

A Vietnam People's Army T-54 tank during operations in the Central Highlands | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

23rd Division (South Vietnam) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Phạm Văn Phú | Hoang Minh Thao | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

78,300 soldiers 488 tanks 374 artillery pieces 134 fighter-bombers 250 helicopters 101 reconnaissance aircraft[1] |

65,141 soldiers 57 tanks 679 vehicles 88 heavy artillery pieces 343 anti-aircraft guns 1,561 anti-tank guns or recoilless guns[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

About 3/4 of all soldiers were killed, wounded, missing or captured. Vast quantities of military hardware were lost.[2] |

600 killed 2,416 wounded[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Ban Me Thuot was a decisive battle of the Vietnam War which led to the complete destruction of South Vietnam's II Corps Tactical Zone. The battle was part of a larger North Vietnamese military operation known as Campaign 275 to capture the Tay Nguyen region, known in the West as the Vietnamese Central Highlands.

In March 1975 the Vietnam People's Army (VPA) 4th Corps staged a large-scale offensive, known as Campaign 275, with the aim of capturing the Central Highlands from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in order to kick-start the first stage of the 1975 Spring Offensive. Within ten days, the North Vietnamese destroyed most South Vietnamese military formations in II Corps Tactical Zone, exposing the severe weaknesses of the South Vietnamese Army. For South Vietnam, the defeat at Ban Me Thuot and the disastrous evacuation from the Central Highlands came about as a result of two major mistakes. Firstly, in the days leading up to the assault on Ban Me Thuot, ARVN Major General Pham Van Phu repeatedly ignored intelligence which showed the presence of several North Vietnamese combat divisions around the district.[3] Secondly, President Nguyen Van Thieu's strategy to withdraw from the Central Highlands was poorly planned and implemented.[4]

In the end, it was the ordinary South Vietnamese soldiers and their families who paid the ultimate price, as North Vietnamese artillery decimated the South Vietnamese military convoy on Route 7.[5]

Background

At the beginning of 1975, members of the North Vietnamese Political Bureau paid close attention to the military situation in South Vietnam to plan for their next major offensive. On January 8, two days after the Vietnam People’s Army 4th Corps had captured Phuoc Long on the northern edges of South Vietnam’s III Corps Tactical Zone, North Vietnamese leaders agreed to launch an all-out military offensive, in order to end the war.[6] Originally the North Vietnamese leaders expected the campaign would last two years, be completed in 1976, and pave the way for final victory. Their key objectives were to bring military pressure closer to Saigon, annihilate as many South Vietnamese military units as possible, and create favourable conditions on the battlefield so that combat forces could be deployed from their current localities.[6]

Following extensive discussions on the fighting ability of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, the Political Bureau approved the General Staff’s plan, which had selected the Central Highlands as the main battlefield for the upcoming offensive.[6] The Central Highlands campaign was codenamed ‘Campaign 275’ and the goal was to capture the city of Ban Me Thuot. To achieve that objective, North Vietnamese General Văn Tiến Dũng placed great emphasis on the principles of massed force, secrecy, and surprise to draw South Vietnamese forces away from the main objective.[7] For the element of surprise to be successful, North Vietnamese forces needed to launch strong diversionary attacks on Pleiku and Kon Tum, thereby leaving Ban Me Thuot completely exposed. Once the element of surprise had been achieved, the North Vietnamese would mass their forces on Ban Me Thuot, and prevent South Vietnamese reinforcements from retaking the city.[7]

Order of battle

North Vietnam

In March 1975 the Vietnam People's Army Central Highlands Front, under the command of General Hoang Minh Thao, were given the responsibility of carrying out Campaign 275 to capture key objectives in the Central Highlands. Major General Vu Lang was the deputy commander, Colonel Dang Vu Hiep was appointed the Front’s political commissar, and Colonel Phi Trieu Ham was the deputy political commissar. The Central Highlands Front fielded five infantry divisions (3rd ‘Gold Star’, 10th, 316th, 320A and 968th Infantry Divisions) and four independent regiments (25th, 271st, 95A, and 95B Infantry Regiments). To support the aforementioned units, North Vietnam deployed the 273rd Armoured Regiment, two artillery units (40th and 675th Artillery Regiments), three air-defence units (232nd, 234th, and 593rd Air-Defence Regiments), two combat engineer units (7th and 575th Combat Engineer Regiments), and the 29th Communications Regiment.[8]

Offensive strategy

Between February 17 and February 19, 1975, North Vietnamese field commanders in the Central Highlands Front held a conference to plan for their upcoming offensive. In order to plan their combat strategy, North Vietnamese commanders assessed the potential obstacles faced by the Vietnam People’s Army and the strength of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in the Central Highlands. Following extensive discussions, North Vietnamese commanders concluded that the South Vietnamese army in the Central Highlands could mobilise about 5–7 regiment-sized units to counter the upcoming offensive. In the worst-case scenario, if South Vietnamese units were not tied up elsewhere, North Vietnamese commanders thought that South Vietnam could probably mobilise between nine to twelve regiments. North Vietnamese commanders believed South Vietnam could deploy about one or two armoured brigades, three to five battalions of artillery, and 80 aircraft per day to support the army. The North Vietnamese commanders within the Central Highlands Front discussed the possibility of the United States re-entering the conflict, which they believed would see the commitment of about 100 fighter-bombers from the United States Seventh Fleet.[9][10]

Aside from dealing with the army formations which South Vietnam might have deployed, the question of where and when to strike was the main problem that concerned the North Vietnamese. After the strength of both armies had been taken into account, the Central Highlands High Command came up with two offensive options. In the first option, the North Vietnamese could avoid the outlying South Vietnamese installations and strike directly at their primary target of Ban Me Thuot. For the first option to be successful, the North Vietnamese had to secure Highways 14, 19, and 21 to isolate Ban Me Thuot, and stop potential South Vietnamese reinforcements. The North Vietnamese favoured the first option, because it would give the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division and other support units little or no time to respond. At the same time, the first option would have enabled a quick victory without inflicting large-scale damage on the civilian population of Ban Me Thuot. In the second option, the North Vietnamese had to destroy all the outlying South Vietnamese defences and then move on to Ban Me Thuot. The Central Highlands Front, under General Hoang Minh Thao's command, ordered all combat units to follow the second option and destroy the defences around Ban Me Thuot, but to be ready to switch to the first option when the opportunity presented itself.[9][10]

South Vietnam

The responsibility for the defence of Ban Me Thuot, located in South Vietnam’s II Corps Zone, was given to Major General Pham Van Phu. The 23rd Division (South Vietnam) was the main unit defending Ban Me Thuot and the surrounding areas. Major General Pham Van Phu had at his disposal five artillery battalions equipped with 146 artillery guns, and one armoured brigade of about 117 tanks and armoured vehicles. The South Vietnamese military also stationed air force and naval units in Ban Me Thuot: they maintained 12 air force squadrons of about 102 fighter-bombers, 164 helicopters, and 69 transport aircraft, and the navy deployed two squadrons on the coast and two squadrons on the rivers.[1]

The Army of the Republic of Vietnam also had the 22nd Division (South Vietnam), seven ranger battalions, 36 regional force battalions, eight artillery battalions equipped with 230 artillery guns, and four armoured brigades in the Central Highlands.

To support those ground units, the South Vietnamese air force had 32 fighter-bombers, 86 helicopters, and 32 transport and reconnaissance aircraft. The ARVN 23rd Infantry Division and other support units were placed under the command of Brigadier General Tran Van Cam. Across the Central Highlands of Vietnam, the South Vietnamese military enjoyed a numerical superiority of about 78,300 soldiers against North Vietnam’s 65,141 soldiers. However, within the vicinity of Ban Me Thuot, the South Vietnamese were actually outnumbered by a ratio of 5:1. The North Vietnamese had more tanks, armoured vehicles, and heavy artillery, with a ratio of about 2:1.[1] North Vietnamese General Van Tien Dung believed his tank and artillery units in the Central Highlands were the key factors that guaranteed a quick victory, because South Vietnam simply lacked the capability to withstand such large numbers of heavy weaponry.[11]

South Vietnamese preparations

On February 18, 1975, President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu gathered all his commanders at the Independence Palace to discuss the Ly Thuong Kiet Military Plan, which was approved by the National Security Council in December 1974. During a briefing by ARVN Colonel Hoang Ngoc Lung, Head of the ARVN General Staff, several important issues were brought to the attention of President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and the ARVN Corps commanders. Firstly, information gathered by the South Vietnamese army showed there were seven North Vietnamese divisions in the northern areas of South Vietnam’s I Corps Tactical Zone. Secondly, there were signs which suggested that the North Vietnamese might launch a large-scale attack during the spring-summer season of 1975. And thirdly, the II Corps Tactical Zone under the command of Major General Pham Van Phu was most likely North Vietnam’s first target. On February 19 General Phu returned to Pleiku to draw up a defence plan.[12]

During the next few days, reports from South Vietnamese intelligence showed that North Vietnam’s 968th Infantry Division had arrived in South Vietnam’s II Corps from Laos. Two divisions (10th and 320A Infantry Divisions) had taken up positions around Pleiku and Kon Tum, while two regiments (271st and 202nd Regiments) had set up their base in Quang Duc.[13] On March 2 a CIA officer flew out from Nha Trang to inform ARVN Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat of North Vietnamese preparations to attack Ban Me Thuot, without offering information on the strength of North Vietnamese formations. In response to the CIA report, General Phu ordered the 53rd Regiment to move from Quang Duc to Ban Me Thuot, and the 45th Regiment from Thuan Man to Thanh An-Don Tham.[14] General Phu did not make any further changes to the South Vietnamese order of battle in or around Ban Me Thuot. Thus, by the time the North Vietnamese opened fire on Ban Me Thuot, General Phu had simply failed to implement an effective plan to save II Corps.[15]

Prelude

Diversions

In February 1975, during the midst of Tet New Year celebrations, a North Vietnamese deserter surrendered himself to the ARVN 2nd Brigade Headquarters. Through extensive interrogations, the North Vietnamese soldier revealed the whereabouts of North Vietnamese units; the 10th Infantry Division had encircled Duc Lap, while the 320A Infantry Division had arrived in Ea H’leo and were gearing up for an assault on Thuan Man, and an unknown unit was heading towards Ban Me Thuot. In late February, North Vietnamese artillery shells began to rain down on Pleiku, which convinced General Phu that the North Vietnamese would attack Pleiku instead of Ban Me Thuot. South Vietnamese military intelligence and information received from the American Embassy in Saigon showed the presence of about two or three North Vietnamese combat divisions positioned about 20 kilometres away from Kontum and Pleiku.[16] Indeed, the movements around Pleiku and Kontum during the month of February were designed by the North Vietnamese Tay Nguyen Front to fool South Vietnamese military commanders in the Central Highlands.[17]

Since December 1974, the North Vietnamese prepared for the offensive by conducting raids on various South Vietnamese outposts and broadcasting fake radio messages to keep South Vietnamese commanders guessing about the location of their next assault. While the South Vietnamese units were kept occupied by Communist diversions, North Vietnamese General Hoang Minh Thao began moving his troops into attacking positions. The VPA 7th Combat Engineer Regiment was tasked with connecting Route 14 at North Vo Dinh with Highway 19 near Mang Yang Pass, which surpassed the district of Kontum. The VPA 10th Infantry Division began withdrawing from Duc Lap, and only left a small force behind to continue the bombardment of Pleiku, as artillery and tanks units took positions north of Kontum. The 320A Infantry Division deployed a small unit west of Pleiku to apply additional pressure on South Vietnamese positions at La Son, Thanh An, and Don Tam. Elements of the 95th Regiment conducted blocking operations along Highway 19 to stop South Vietnamese reinforcements from reaching their destination. The 198th Special Forces Regiment raided South Vietnamese depots at Pleiku, while the main formation of the 10th and 320A Infantry Divisions marched on Ban Me Thuot.[18][19]

Personnel from local Viet Cong units infiltrated Kontum and Pleiku to spread rumours of a ‘big Communist offensive’ on the aforementioned districts.[18] In response to the rumours, the ARVN 45th Infantry Regiment was sent out to sweep the areas near Ban Me Thuot, Thuan Man, and Duc Lap. To maintain the secrecy of their operations, the North Vietnamese Tay Nguyen Front ordered the 320A Infantry Division, which had by then set up camp west of Ban Me Thuot, to avoid contact with the South Vietnamese. Upon their arrival from Laos, the 316th Infantry Division received similar orders, and was not allowed to open fire under any circumstances.[19] As the events in South Vietnam’s II Corps Tactical Zone were beginning to unfold, intelligence reports from Saigon continued to warn General Phu of an imminent Communist onslaught on Ban Me Thuot. Despite the numerous warnings which he had received from the CIA and his own military intelligence, General Phu remained convinced that Pleiku would be North Vietnam’s next target. As a result, on February 18, 1975, he ordered the 23rd Infantry Division to remain at their positions in Kontum and Pleiku, thereby reversing his earlier decision to bolster South Vietnamese defences at Ban Me Thuot.[20]

Closing in

On March 3, 1975, North Vietnam’s Campaign 275 against South Vietnamese military forces in the Central Highlands began. The 95A Regiment was the first unit to go into action when they destroyed one South Vietnamese regional force battalion and successfully secured a 20-kilometre stretch of road on Highway 19 connecting Ayun with Pleibon and Phu Yen. Later, elements of the North Vietnamese 3rd ‘Gold Star’ Division secured a section of Highway 19 at Thuong An that connected with Bridge no.13 at Dong An Khe, killing about 300 South Vietnamese soldiers.[21] On the night of March 5, the North Vietnamese 25th Regiment ambushed a South Vietnamese transportation convoy at Chi Cuc and cut off Highway 21 west of Ban Me Thuot. To keep all the main roads open, Phu sent reinforcements to defend a section of Highway 19 at the eastern side of Peiku and ordered the ARVN 45th Infantry Regiment to march back from Thuan Man to defend Route 14 at southern Pleiku. The ARVN 53rd Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Vu The Quang, was redeployed from Quang Duc Province to defend Ban Me Thuot. By March 8, the North Vietnamese army had completely isolated the South Vietnamese II Corps Tactical Zone from the rest of the country. Route 7, which had not been used for a long time due to neglect, was the only road still open.[22]

On March 5 Quang sent one of his battalions to Ban Me Thuot in a convoy of 14 vehicles. They were ambushed by the North Vietnamese 9th Regiment, 320A Infantry Division at Thuan Man. Eight vehicles were destroyed, while two 150mm artillery guns were captured by the North Vietnamese.[23] The remaining seven vehicles had to turn back, and Quang returned to Ban Me Thuot on a helicopter. On March 7 the North Vietnamese 48th Regiment, 320A Infantry Division, captured Chu Se and Thuan Man, and took 121 soldiers prisoner. On March 9 Phu ordered the 21st Ranger Battalion to fly out from Pleiku to support the 53rd Infantry Regiment in their efforts to retake Thuan Man. During the early hours of March 9, as the 21st Ranger Battalion and the 53rd Infantry Regiment were repeatedly beaten back in their attempts to retake Thuan Man, the under-strength North Vietnamese 10th Regiment captured Duc Lap and the surrounding areas.[24]

At 11 am on March 9, Phu flew out to Ban Me Thuot to assess the military situation with Brigadier General Le Trung Tuong, Colonel Vu The Quang, and Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat. Phu admitted that the situation at Duc Lap was irreversible. The 21st Ranger Battalion was reassigned to the north of Ban Me Thuot, the 2nd Battalion of the 53rd Infantry Regiment was to defend Dac Sac, and when the opportunity arose they would be tasked with retaking Duc Lap. Subsequently, Quang was entrusted with the task of defending Ban Me Thuot. Despite the strong presence of two North Vietnamese divisions outside Ban Me Thuot, Phu believed the situation outside the district was only a mere diversion attempt, and the real target would be Pleiku. Thus, upon arrival at his Pleiku headquarters, he raised the level of alertness there to 100%. While Phu was waiting for the enemy to assault Pleiku, the North Vietnamese 7th and 575th Combat Engineer Regiments cleared the main roads into Ban Me Thuot to ensure tanks and heavy artillery could be directed at the district without hindrance. By the early hours of March 10, the North Vietnamese army was in a strong position to strike at Ban Me Thuot.[25]

Battle

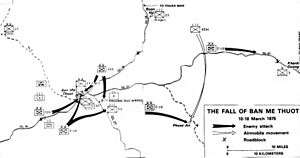

Fall of Ban Me Thuot

At 2 am on March 10, 1975, the North Vietnamese army began their assault on South Vietnamese forces at Ban Me Thuot. The North Vietnamese 198th Special Forces Regiment spearheaded the attack by hitting the Hoa Binh Airfield, the district of Mai Hac De, and the headquarters of the ARVN 53rd Infantry Regiment. The initial North Vietnamese attack, which was marked by heavy artillery bombardment and actions initiated by the 198th Special Forces Regiment, had shocked ARVN Colonels Nguyen Trong Luat and Vu The Quang, both subordinates of Major General Pham Van Phu. Despite the strength of the initial assault, Quang believed the North Vietnamese only wanted to cause disruption and would withdraw their forces by daybreak.[26] By 3:30 am, the 4th Battalion, 198th Special Forces Regiment, had successfully secured Phan Chu Trinh Road and the southern part of Hoa Binh airport, and they waited there for the regular infantry and tank units to arrive.[27]

The North Vietnamese 5th Battalion, 198th Special Forces Regiment continued their assault on South Vietnamese installations at Mai Hac De district and the headquarters of the ARVN 53rd Infantry Regiment. The 5th Battalion successfully overran the nearby South Vietnamese artillery position and the tactical operations centre, thereby establishing control over the battlefield. By 5 am all main roads leading into the city of Ban Me Thuot were completely under North Vietnamese control. As the sun rose, the North Vietnamese continued to pound South Vietnamese positions around Ban Me Thuot with heavy artillery to cover the next wave of infantry assaults. During the morning of March 10, North Vietnamese infantry units attacked Ban Me Thuot from different directions along the main roads. The 174th Regiment, with one armoured battalion in support, marched through Chi Lang, Chu Di, and Mai Hac De from the northwest. As the 95B Regiment approached Ban Me Thuot from the northeast, the main formation of the 149th Regiment secured Chu Blom and marched towards Ban Me Thuot from the southeast. The 1st Battalion, 3rd Regiment and the 1st Battalion, 149th Regiment launched an assault on Hoa Binh airfield from the northeast and southwest respectively. At the same time, the 2nd Regiment captured the South Vietnamese installation at Phuoc An.[28]

In an attempt to halt the North Vietnamese assault, Luat ordered two squadrons of M-113 armoured personnel carriers to confront the enemy at Nga Sau, but they were forced to turn back by tanks from the North Vietnamese 3rd Tank Battalion, 273rd Armoured Regiment.[29] At around 5:30 pm, a South Vietnamese ranger battalion was forced to abandon the nearby installation at Dac Lac after continuous assaults from the 95B Regiment. In the northeast, the South Vietnamese 9th Ranger Battalion held off the North Vietnamese 95B Regiment until they abandoned their positions on the next day. In the western outskirts of Ban Me Thuot, eight A-37 Dragonfly bombers from the South Vietnamese 6th Air Force Division inflicted light casualties on the North Vietnamese 24th Regiment, but failed to stop their enemies’ momentum. In the southwest, Quang tried to retake Mai Hac De by mobilising his reserve units with tactical air support. Meanwhile, in the south-eastern end of Ban Me Thuot, the North Vietnamese 149th Regiment defeated the South Vietnamese 53rd Infantry Regiment, after they sustained heavy casualties from repeated air attacks from A-37 bombers.[30]

Earlier in the day, at about 2:30 pm, South Vietnamese Colonel Trinh Tieu, Chief of the ARVN 2nd Brigade in II Corps, discovered that the North Vietnamese 316th Infantry Division had moved into positions south of Ban Me Thuot from their base in Laos. To stop them from advancing any further, Phu ordered his soldiers to destroy every bridge connected to Highway 14. By the time Phu’s order was carried out, elements of the North Vietnamese 316th Infantry Division had engaged in clashes with the South Vietnamese for more than 10 hours. By 5 pm the North Vietnamese 8th Battalion, 149th Regiment, in combination with the 198th Special Forces Regiment, tried but failed to capture Hoa Binh airfield, which was defended by one South Vietnamese ranger battalion.[31]

During the night of March 10, there was a lull in the fighting around Ban Me Thuot. South Vietnamese soldiers began retreating to various points around the headquarters of the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division, the Hoa Binh airfield, and the radio station. Colonel Quang, in a desperate attempt to save Ban Me Thuot, called on Brigadier General Le Trung Tuong to send reinforcements; none were sent. In the early hours of March 11, the North Vietnamese army resumed their assault under continuous bombing runs from South Vietnamese air force A-37 Dragonfly bombers. At 7:55 am, the South Vietnamese air force, while trying to stop a dozen North Vietnamese tanks from advancing toward their objective, accidentally dropped two bombs on the headquarters of the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division. From that point on, the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division lost all contact with the ARVN 2nd Brigade Command Headquarters.[32] At 11 am on March 11, the North Vietnamese 316th Infantry Division established full control over Ban Me Thuot after South Vietnamese soldiers within the city realised that they had been defeated and that no reinforcements had been sent. Thus, only Hoa Binh airfield was still in South Vietnamese hands, with the under-strength ARVN 21st Ranger Battalion and the 53rd Infantry Regiment defending the area.[33]

Counterattack

On March 12, all South Vietnamese soldiers who had survived the North Vietnamese assault gathered at the headquarters of the 23rd Infantry Division and Hoa Binh airfield. Unfortunately, those soldiers were without their leaders, because both Colonels Nguyen Trong Luat and Vu The Quang were captured by the North Vietnamese in the early hours of the day. From Saigon, President Nguyen Van Thieu ordered Phu to hold all South Vietnamese positions at the eastern end of Ban Me Thuot, where they could stage a counter-attack. Phu drew up a plan to retake Ban Me Thuot that would involve the last two remaining regiments (44th and 45th Infantry Regiments) of the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division and the soldiers who had gathered at the 23rd Infantry Division headquarters and Hoa Binh airfield. Thieu approved the plan at dawn, and authorised Phu to make full use of three South Vietnamese air force units (6th Air Force Division belonging to the ARVN 2nd Brigade, 1st Air Force Division at Da Nang, and the 4th Air Force Division at Cần Thơ).[34]

On the afternoon of March 12, elements of the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division were dropped off at designated landing zones around Phuoc An. Initially about 100 South Vietnamese helicopters participated in the operation, and 81 fighter-bombers were deployed to strike at North Vietnamese positions to cover the landings. At 3:10 pm, Phu took off in his Cessna U-17 to direct the operation over the skies of Ban Me Thuot. As he approached the battlefield, Phu phoned the South Vietnamese units at Hoa Binh airfield to notify them that an operation was underway, and he encouraged the soldiers to hold on to their positions. On the morning of March 13, another 145 helicopters were used to complete the first phase of the operation with the entire 44th Infantry Regiment, the last soldiers of the 45th Infantry Regiment, and the 232nd Artillery Battalion dropped off at various points in Nong Trai, Phuoc An and along Highway 21. At the completion of the landing operation, Phu returned to Pleiku to have a meeting with Thieu, during which they discussed the sudden appearance of the North Vietnamese 316th Infantry Division.[35]

While the South Vietnamese air force was transporting the 23rd Infantry Division to the battlefield, their airbase at Cu Hanh was subjected to artillery bombardment from the North Vietnamese 968th Infantry Division. The North Vietnamese Central Highlands Front had anticipated the South Vietnamese military's movements, so they built up their forces in and around Ban Me Thuot to prepare for a South Vietnamese counter-attack.[36] On March 13, the North Vietnamese 24th and 28th Regiments received two companies of armoured vehicles and one artillery battalion, which had begun raining artillery shells on Phuoc An. At 7:07 am on March 14, even before the ARVN 44th and 45th Infantry Regiments began their combat operations, the North Vietnamese 24th Regiment opened fire and attacked the South Vietnamese, with support from the 273rd Armoured Regiment.[37]

By midday on March 14, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the ARVN 45th Infantry Regiment slowly melted away, as they were squeezed from all sides by the North Vietnamese 24th Regiment. Rather than marching on to Ban Me Thuot to relieve the soldiers of the 45th Infantry Regiment, the ARVN 44th Infantry Regiment were pinned down to fight the enemies’ 24th Regiment. On March 16, South Vietnamese formations at Phuoc An and Nong Trai came under heavy attack. At 8:15 am the 3rd Battalion, the last unit from the ARVN 45th Infantry Regiment, was completely wiped out. Subsequently, all South Vietnamese soldiers at Nong Trai were captured along with one helicopter. On March 17 General Hoang Minh Thao ordered the 28th Regiment and the rest of the 273rd Armoured Regiment to support the 24th Regiment in their efforts to capture Phuoc An. At the same time, the North Vietnamese 66th Regiment and the 198th Special Forces Regiment began their final push on Hoa Binh airfield. At 11:30 am, South Vietnamese soldiers at Hoa Binh airfield, mainly drawn from the 53rd Infantry Regiment and the 21st Ranger Battalion, were finally defeated. Simultaneously, the remnants of the ARVN 44th Infantry Regiment abandoned Phuoc An, leaving the North Vietnamese in complete control of Ban Me Thuot.[38]

Retreat

While battles were raging in and around Ban Me Thuot, South Vietnamese military forces in I Corps Tactical Zone were under pressure by the North Vietnamese 324th and 325th Infantry Divisions. During the period from March 8 to March 13, there were clashes in Truoi in southern Hue, Mai Linh, Mo Tau, Thien Phuoc, and Quang Ngai. As a result of the immense pressure placed upon I Corps, the ARVN General Staff could not deploy strong units from the region to defend Ban Me Thuot and the rest of II Corps.[39] On March 11 Thieu convened a meeting with Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm, Chief of the ARVN General Staff General Cao Văn Viên, and Lieutenant General Dang Van Quang to discuss the military situation in the northern provinces of South Vietnam. In this meeting, Thieu decided to withdraw what was left of his army from the northern provinces to defend the Mekong region, where most of the nation’s population and vital economic resources were located. Thieu justified his decision on the basis that the South Vietnamese military could not defend every inch of South Vietnam’s territory, so the military had to be ‘lightened at the top and heavy at the bottom’.[40]

Starting at 11 am on March 14, Thieu flew out to Cam Ranh for a briefing with General Phu. The events which took place after this briefing would go down as one of the greatest failures in military history.[41] After Phu had outlined the military situation in the Central Highlands, he asked Thieu to bolster the South Vietnamese 6th Air Force Division with more aircraft and additional brigades to defend Kontum and Pleiku. Thieu refused to send further reinforcements because the South Vietnamese military no longer had the resources. Phu was ordered to move all his units down to the Mekong region where they could continue fighting. General Vien cautioned against moving large military formations down Highway 19; he reminded Thieu of the destruction suffered by the French Mobile Group 100 in the region in 1954. Thieu and his commanders made the decision to use Route 7 instead, in an attempt to surprise the North Vietnamese, who would not expect them to use that road due to its poor condition.[42]

After the briefing Phu immediately returned to his headquarters in Pleiku, where he began planning for the withdrawal with Brigadier Generals Tran Van Cam, Pham Ngoc Sang, Pham Duy Tat, and Colonel Le Khac Ly. To maintain secrecy, Phu ordered his officers to issue orders using only word of mouth instead of written documents, and not to reveal the withdrawal plan to local regional forces. Furthermore, he stated that the abandonment of II Corps Tactical Zone had to be quick, with the army taking only enough military equipment and ammunition to fight one last battle. Generals Tat and Cam were assigned the task of supervising the movements of soldiers and their dependents on the ground. Sang was responsible for the movement of vital military equipment and supplies via air transport and to sweep Route 7 using air force fighter-bombers. Ly was ordered to lead a group of combat engineers to repair the road and bridges on Route 7, as well as maintain contact with the ARVN 2nd Brigade Headquarters in Nha Trang. The plan was destined to fail, as Phu was unaware that General Ngo Quang Truong, commander of I Corps Tactical Zone, had also received similar orders to evacuate.[43]

Disaster on Route 7

Although local commanders in II Corps Tactical Zone tried their best to maintain secrecy, the unusual movement of transport aircraft in Pleiku on March 14 stirred up concern and suspicion amongst soldiers and civilians in the area. On March 15 the concerns of civilians were further heightened when a convoy of transport vehicles belonging to the 6th and 23rd Ranger Battalions headed south from Kontum. On the afternoon of March 15, the withdrawal of South Vietnamese forces began to pick up momentum. The ARVN 19th Armoured Cavalry Squadron and the 6th Ranger Battalion opened the main road which stretched from Pleiku to Phu Tuc. Behind them were various infantry, armoured vehicle, and support units. During the early phases of the operation, Phu was confident that his plan would succeed for two reasons. Firstly, he believed most North Vietnamese units were busy stopping the counter-attack at Phuoc An waged by the ARVN 23rd Infantry Division and would not have the time to disrupt the withdrawal. Secondly, if the North Vietnamese 968th Infantry Division near Pleiku was deployed to stop the operation, it would have to overcome the formidable ARVN 25th Ranger Battalion which was tasked with stopping any North Vietnamese attacks.[44][45]

For North Vietnamese field commanders of the Tay Nguyen Front, the withdrawal of South Vietnamese military forces from II Corps Tactical Zone came as a surprise, but it was not totally unexpected. What surprised the North Vietnamese the most was the speed of the withdrawal. Indeed, it was not until the evening of March 15, when the ARVN 19th Armoured Cavalry Squadron reached Cheo Reo, that the North Vietnamese began to receive information of Saigon’s decision to abandon the Central Highlands. At 8 pm on March 16, the Tay Nguyen Front Command issued the first orders to pursue the South Vietnamese.[46] The North Vietnamese 9th Battalion, 64th Regiment, part of the 320A Infantry Division, was the first unit to be mobilised to intercept the South Vietnamese column south of Cheo Reo district. Subsequently, the entire North Vietnamese 320A Infantry Division was sent to destroy the South Vietnamese column along Route 7, with the 2nd Tank Battalion of the 273rd Armoured Regiment, the 675th Regiment, and the 593rd Anti-Aircraft Regiment in support. By the early hours of March 17, tanks from the ARVN 19th Armoured Cavalry Squadron and the 6th Ranger Battalion clashed with the North Vietnamese 9th Battalion, 64th Regiment at Tuna Pass, about 4 kilometres away from the district of Cheo Reo.[46]

During the evening of March 17, General Tat organised a counter-attack against the enemy's 9th Battalion with support from fighter-bombers, tanks and artillery, but his troops were repeatedly beaten back in their attempt to keep the road open.[47] By the early hours of March 18, the entire North Vietnamese 64th Regiment had blocked all the routes around Tuna Pass, while the 48th Regiment and elements of the North Vietnamese 968th Infantry Division began closing in on Cheo Reo from three directions. In the afternoon, Phu sent the 25th Ranger Battalion and the 2nd Armoured Cavalry Brigade to reopen Route 7. At the same time the North Vietnamese 675th Artillery Regiment began shelling the main South Vietnamese column in Cheo Reo as three infantry regiments attacked the convoy from all sides. Unfortunately for the South Vietnamese, all their attempts to organise strong resistance were stifled by the chaos created by North Vietnamese artillery bombardments. At 3 pm, General Tat was ordered to destroy all heavy weaponry so the North Vietnamese could not make use of it. About 30 minutes later, a UH-1 helicopter landed on the grounds of Phu Bon primary school to pick up Tat and flew off to Nha Trang.[48] At 9 am on March 19, all South Vietnamese soldiers in the district of Cheo Reo stopped fighting. The 6th Ranger Battalion and the 19th Armoured Cavalry Squadron became the only units to arrive at their destination at Cung Son with only light casualties.[49]

Aftermath

The loss of Ban Me Thuot and the subsequent evacuation from the Central Highlands cost South Vietnam’s II Corps Tactical Zone more than 75% of its combat units—the 23rd Infantry Division, the Ranger groups, tanks, armoured cavalry, artillery, and combat engineering units. Overall about 3/4 of all South Vietnamese army soldiers were killed, wounded, deserted, or missing. North Vietnamese casualties were light in comparison, with 600 soldiers killed and 2,416 wounded.[50] Official Vietnamese history informs that during the eight days of fighting, North Vietnam's army put 28,514 South Vietnamese officers and soldiers out of action; 4,502 were killed in action and 16,822 were captured. The North Vietnamese army destroyed 17,183 small arms of various kinds, 79 artillery pieces, and 207 tanks and armoured vehicles; 44 aircraft were shot down and another 110 were damaged.[51]

Civilians who took part in the evacuation suffered the consequences of the military action along Route 7. Most of the civilians who followed the military convoy were either relatives of soldiers or officers in the army, or were government civil servants. Of the estimated 400,000 civilians who initially took part in the march, only a handful actually reached their destinations in the Mekong region. In addition to the casualties inflicted upon them by North Vietnamese artillery, the civilians were also hit by air strikes from the South Vietnamese air force. As a result of those huge losses, Route 7 became known as the ‘convoy of tears’.[5]

South Vietnamese mistakes

The collapse of South Vietnamese forces in the Central Highlands came about as a result of three major factors. Firstly, during much of the war, President Nguyen Van Thieu’s confidence in the ARVN’s intelligence could not be shaken. However, following the capitulation of Ban Me Thuot, Thieu lost all faith in his own military intelligence agencies, when it became evidently clear that the strength of North Vietnamese forces was far greater than what South Vietnamese intelligence agencies had gathered.[52] Consequently, Thieu completely ignored his own military intelligence and the CIA, and made all military decisions by himself without consulting the Joint General Staff. Thus, when Major-General Pham Van Phu requested that Thieu send reinforcements to bolster the strength of South Vietnamese forces in the Central Highlands, Thieu gave him two options: either carry out the President’s orders, or be replaced by somebody who was willing to do so. General Phu chose to implement Thieu’s orders and evacuated his units from II Corps.[53]

The second factor which contributed to the destruction of the ARVN 2nd Brigade, II Corps Tactical Zone, was the inability of South Vietnamese commanders to coordinate the withdrawal. In the process of pulling out from the Central Highlands, large numbers of South Vietnamese soldiers and heavy military equipment were stretched out along the narrow corridor of Route 7. Behind the military formation were huge numbers of South Vietnamese civilians who were relatives of the military personnel, as well as government officials and their families.[54] Unfortunately for the South Vietnamese soldiers on the ground, their army simply lacked the logistical system required to maintain the element of secrecy, which South Vietnamese commanders had hoped would enable them to pull out from the region without drawing too much attention from the North Vietnamese. It is hard to fathom how South Vietnamese commanders hoped to move 400,000 civilians in utmost secrecy. So when North Vietnamese forces attacked the South Vietnamese column along Route 7, there was little South Vietnamese commanders could do to prevent the destruction of their units.[54]

The third factor which led to the quick disintegration of II Corps was the poor state of morale amongst the soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. By 1975, the morale of South Vietnamese soldiers and their commanding officers had reached its lowest point as the war continued to drag on with no end in sight. The determination of the ARVN officer corps had taken a serious blow when South Vietnamese Foreign Minister Tran Van Lam returned from the United States in February 1975, and reported that no additional military or economic aid had been offered.[55] When the order was given to abandon the Central Highlands, the primary concern of South Vietnamese military personnel was not battlefield victories, but the welfare of their families. Consequently, when the North Vietnamese attacked South Vietnamese forces on Route 7, large numbers of South Vietnamese soldiers left the battlefield to search for their families amidst the chaos. During the final days of South Vietnam’s existence, the average South Vietnamese soldier showed more loyalty to his family than to his commanding officer, which had a significant impact on his willingness to fight on.[55]

During the First Indochina War (1945 to 1954), both Viet Minh and French forces considered the Central Highlands to be their ‘home’, as it was considered the key to domination in Indochina. Both sides recognised that in order to occupy the Central Highlands, they had to possess a sufficient reserve of manpower with which to control the strategic areas within the region. By 1975, the South Vietnamese military could no longer afford to maintain a large strategic reserve.[56] South Vietnamese units in II Corps were overstretched in various locations across the Central Highlands, and could easily be overrun by enemy forces. Although Thieu’s decision to abandon the region was made with the aim of saving the military formations of II Corps, the decision nonetheless turned into a death warrant for General Phu’s men and their families. The lack of coordination and poor organisation during the withdrawal operation not only led to the destruction of II Corps, but marked the beginning of the end for South Vietnam.[56]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Duong Hao, pp. 149–151

- 1 2 Hoang Minh Thao, 1979, p. 153

- ↑ Frank Snepp, p. 43–51

- ↑ Le Dai Anh Kiet, p.149

- 1 2 George C. Herring, p.259

- 1 2 3 LeGro (1981), p.147

- 1 2 LeGro (1981), p.148

- ↑ Nguyen Van Bieu, p.292

- 1 2 Nguyen Van Bieu, pp.292

- 1 2 Hoang Minh Thao, p.153

- ↑ Van Tien Dung, p. 19

- ↑ Can Van Vien, p. 211

- ↑ Duong Hao, p.148

- ↑ Frank Snepp, pp.45–46

- ↑ Frank Snepp, p.46

- ↑ Le Dai Anh Kiet, pp. 138

- ↑ Nguyen Van Bieu, p.298

- 1 2 Nguyen Van Bieu, p. 298

- 1 2 Hoang Minh Thai, p. 148

- ↑ Frank Snepp, pp. 43–45

- ↑ Vietnam People’s Army, p. 89

- ↑ Le Dai Anh Kiet, p. 141

- ↑ Vietnam People’s Army, p. 94

- ↑ Le Dai Anh Kiet, p. 142

- ↑ Frank Snepp, pp. 43–51

- ↑ Duong Hao, p.156

- ↑ Nguyen Van Bieu, p.338

- ↑ Vietnam People’s Army, p.104

- ↑ Pham Ngoc Thach & Ho Khang, p.246

- ↑ Nguyen Van Bieu, p.304–305

- ↑ Hoang Minh Thao, p.198

- ↑ Frank Snepp, p.47

- ↑ Hoang Minh Thao p.197

- ↑ Duong Hao, p.158

- ↑ Hoang Minh Thao, p.204

- ↑ Hoang Minh Thao, p.211

- ↑ Nguyen Van Bieu, pp. 310–311

- ↑ Nguyen Van Bieu, p.311

- ↑ Phillip B. Davidson, pp.569–570

- ↑ Cao Van Vien, p.132

- ↑ Le Dai anh Kiet, p.149

- ↑ Duong Hao, p.166

- ↑ Duong Hao, pp.157–169

- ↑ Duong Hao, pp.173–174

- ↑ Frank Snepp, p.50

- 1 2 Hoang Minh Thao, 2004, p.234

- ↑ Duong Hao, p.176

- ↑ Le Dai Anh Kiet, p.151

- ↑ Duong Hao, p.178

- ↑ Pham Ngoc Thach & Ho Khang, p.273

- ↑ Vietnam People's Army, p.94

- ↑ Frank Snepp, p.48

- ↑ Alan Dawson, p.16

- 1 2 Duong Hao, p.179

- 1 2 Gabriel Kolko, p.389

- 1 2 Alan Dawson, p.14

References

- Cao, Vien V. (1983). The Final Collapse. Washington: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 7555500.

- Caputo, Phillip (2005). 10,000 Days of Thunder: History of the Vietnam War. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-86231-1.

- Davidson, Phillip B. (1988). Vietnam at War: A History 1946–1975. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506792-7.

- Dawson, Alan (1977). 55 Days: Fall of South Vietnam. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-314476-5.

- Duong, Hao (1980). A Tragic Chapter. Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House. OCLC 10022184.

- Herring, George C. (1979). America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam 1950–1975. Boston: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-253618-8.

- Hoang, Thao M. (1979). Victory of the Tay Nguyen Campaign. Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House. OCLC 21749012.

- Hoang, Thao M. (2004). Fighting on the Tay Nguyen Front. Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House. OCLC 58535754.

- Kolko, Gabriel (2003). Anatomy of a War (Translated by Nguyen Tan Cuu). Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-56584-218-2.

- Le, Kiet A.D. (2003). The Narratives of Saigon Generals. Hanoi: People’s Police Publishing House.

- LeGro, William E. (1981). From Cease-fire to Capitulation. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-1-4102-2542-9.

- Nguyen, Bieu V. (2005). The Army at the Tay Nguyen Front-3rd Corps. Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House.

- Pham, Thach N. Ho, Khang (2008). History of the War of Resistance against America (8th edition). Hanoi: National Political Publishing House.

- Snepp, Frank (2001). A Disastrous Retreat. Ho Chi Minh City: Ho Chi Minh City Publishing.

- Van, Dung T. (1976). The Great Spring Victory of 1975. Hanoi: People’s Army Publishing House. OCLC 2968693.

- Vietnam People’s Army (2005). The General Offensive and General Uprising. Ho Chi Minh City: Ho Chi Minh City Publishing.

Coordinates: 12°41′N 108°04′E / 12.68°N 108.06°E