Battle of the Bulge

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

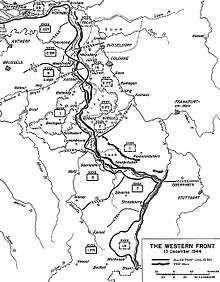

Map showing the swelling of "the Bulge" as the German offensive progressed creating the nose-like salient during 16–25 December 1944.

Front line, 16 December

Front line, 20 December

Front line, 25 December

Allied movements

German movements

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of the Bulge (16 December 1944 – 25 January 1945) was a major German offensive campaign launched through the densely forested Ardennes region of Wallonia in Belgium, France, and Luxembourg on the Western Front toward the end of World War II in Europe. The surprise attack caught the Allied forces completely off guard. United States forces bore the brunt of the attack and incurred their highest casualties for any operation during the war. The battle also severely depleted Germany's armored forces on the western front, and Germany was largely unable to replace them. German personnel, and later Luftwaffe aircraft (in the concluding stages of the engagement), also sustained heavy losses.

Different forces referred to the battle by different names. The Germans referred to it officially as Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein ("Operation Watch on the Rhine") or usually Ardennenoffensive or Rundstedt-Offensive, while the French named it the Bataille des Ardennes ("Battle of the Ardennes"). The Allies called it the Ardennes Counteroffensive. The phrase "Battle of the Bulge" was coined by contemporary press to describe the way the Allied front line bulged inward on wartime news maps[23][lower-alpha 9][24] and became the most widely used name for the battle.

The German offensive was supported by several subordinate actions including Operations Unternehmen Bodenplatte, Greif and Währung. As well as stopping Allied transport over the channel to the port city of Antwerp, these operations were intended to split the British and American Allied line in half, so the Germans could then proceed to encircle and destroy four Allied armies, forcing the Western Allies to negotiate a peace treaty in the Axis Powers' favor. Once that was accomplished, Hitler could fully concentrate on the eastern theatre of war.

The offensive was planned by the German forces with utmost secrecy, minimizing radio traffic and moving troops and equipment under cover of darkness. Intercepted German communications indicating a substantial German offensive preparation were not acted upon by the Allies.[25][26]

The Germans achieved total surprise on the morning of 16 December 1944 due to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with Allied offensive plans, and poor aerial reconnaissance. The Germans attacked a weakly defended section of the Allied line, taking advantage of heavily overcast weather conditions, which grounded the Allies' overwhelmingly superior air forces. Fierce resistance on the northern shoulder of the offensive around Elsenborn Ridge and in the south around Bastogne blocked German access to key roads to the northwest and west that they counted on for success. Columns of armor and infantry that were supposed to advance along parallel routes found themselves on the same roads. This and terrain that favored the defenders threw the German advance behind schedule and allowed the Allies to reinforce the thinly placed troops. Improved weather conditions permitted air attacks on German forces and supply lines, which sealed the failure of the offensive. In the wake of the defeat, many experienced German units were left severely depleted of men and equipment, as survivors retreated to the defenses of the Siegfried Line.

The Germans' initial attack included 200,000 men, 340 tanks and 280 assault guns. These were reinforced a couple weeks later, bringing the offensive's total strength to 300,000 troops, 1,500+ tanks and assault guns, 2,400 aircraft, and several thousand field guns and mortars. Between 67,200 and 125,000 of their men were killed, missing or wounded. For the Americans, 610,000 men were involved in the battle,[4] of whom 89,000 were casualties,[15] including up to 19,000 killed.[15][27] Along with the Battle of Okinawa and the Battle of Luzon, it was one of the largest and bloodiest battles fought by the United States in World War II.[28][29][30]

Background

After the breakout from Normandy at the end of July 1944 and the landings in southern France on 15 August 1944, the Allies advanced toward Germany more quickly than anticipated.[lower-alpha 10] The Allies were faced with several military logistics issues: troops were fatigued by weeks of continuous combat, supply lines were stretched extremely thin, and supplies were dangerously depleted. General Eisenhower (the Supreme Allied Commander) and his staff chose to hold the Ardennes region which was occupied by the First United States Army. The Allies believed the Ardennes could be defended by as few troops as possible due to the favorable terrain (a densely wooded highland with deep river valleys and a rather thin road network) and a limited number of Allied operational objectives. Also, the Wehrmacht was known to be using the area to the east across the German border (the Eifel region, which is the geological continuation of the Ardennes) as a rest-and-refit area for its troops.[31]

The speed of the Allied advance coupled with an initial lack of deep-water ports presented the Allies with enormous supply problems.[32] Over-the-beach supply operations using the Normandy landing areas and direct landing LSTs on the beaches were unable to meet operational needs. The only deep-water port the Allies had captured was Cherbourg on the northern shore of the Cotentin peninsula and west of the original invasion beaches,[32] but the Germans had thoroughly wrecked and mined the harbor before it could be taken. It took many months to rebuild its cargo-handling capability. The Allies captured the port of Antwerp intact in the first days of September, but it was not operational until 28 November. The estuary of the Schelde river (also called Scheldt) that controlled access to the port had to be cleared of both German troops and naval mines.[33] The limitations led to differences between General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery over whether Montgomery or American General Omar Bradley in the south would get priority access to supplies.[34]

German forces remained in control of several major ports on the English Channel coast until May 1945. The extensive destruction of the French railway system prior to D-Day, successful in hampering German response to the invasion, proved equally damaging to the Allies, as it took time to repair the system's tracks and bridges. A trucking system nicknamed the Red Ball Express brought supplies to front-line troops, but used up five times as much fuel to reach the front line near the Belgian border as was delivered. By early October, the Allies had suspended major offensives to improve their supply lines and availability.[32]

Montgomery and Bradley both pressed for priority delivery of supplies to their respective armies so they could continue their individual lines of advance and maintain pressure on the Germans. Eisenhower, however, preferred a broad-front strategy. He gave some priority to Montgomery's northern forces, which had the short-term goal of opening the urgently needed port of Antwerp and the long-term goal of capturing the Ruhr area, the biggest industrial area of Germany.[32] With the Allies stalled, German Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt was able to reorganize the disrupted German armies into a coherent defence.[32]

Field Marshal Montgomery's Operation Market Garden only achieved some of its objectives, while its territorial gains left the Allied supply situation worse off than before. In October, the Canadian First Army fought the Battle of the Scheldt, opening the port of Antwerp to shipping. As a result, by the end of October the supply situation had eased somewhat.

Despite a lull along the front after the Scheldt battles, the German situation remained dire. While operations continued in the autumn, notably the Lorraine Campaign, the Battle of Aachen and fighting in the Hürtgen Forest, the strategic situation in the west had changed little. The Allies were slowly pushing towards Germany, but no decisive breakthrough was achieved. The Western Allies already had 96 divisions at or near the front, with an estimated ten more divisions en route from the United Kingdom. Additional Allied airborne units remained in England. The Germans could field a total of 55 understrength divisions.[3]:1

Adolf Hitler promised his generals a total of 18 infantry and 12 armored or mechanized divisions "for planning purposes." The plan was to pull 13 infantry divisions, two parachute divisions and six panzer-type divisions from the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) strategic reserve. On the Eastern Front, the Soviets' Operation Bagration during the summer had destroyed much of Germany's Army Group Center (Heeresgruppe Mitte). The extremely swift operation ended only when the advancing Red Army forces outran their supplies. By November, it was clear that Soviet forces were preparing for a winter offensive.[35]

Meanwhile, the Allied air offensive of early 1944 had effectively grounded the Luftwaffe, leaving the German Army with little battlefield intelligence and no way to interdict Allied supplies. The converse was equally damaging; daytime movement of German forces was almost instantly noticed, and interdiction of supplies combined with the bombing of the Romanian oil fields starved Germany of oil and gasoline.

One of the few advantages held by the German forces in November 1944 was that they were no longer defending all of Western Europe. Their front lines in the west had been considerably shortened by the Allied offensive and were much closer to the German heartland. This drastically reduced their supply problems despite Allied control of the air. Additionally, their extensive telephone and telegraph network meant that radios were no longer necessary for communications, which lessened the effectiveness of Allied Ultra intercepts. Nevertheless, some 40–50 messages per day were decrypted by Ultra. They recorded the quadrupling of German fighter forces and a term used in an intercepted Luftwaffe message—Jägeraufmarsch (literally "Hunter Deployment")—implied preparation for an offensive operation. Ultra also picked up communiqués regarding extensive rail and road movements in the region, as well as orders that movements should be made on time.[36]

Drafting the offensive

The German Führer Adolf Hitler felt that his mobile reserves allowed him to mount one major offensive. Although he realized nothing significant could be accomplished in the Eastern Front, he still believed an offensive against the Western Allies, whom he considered militarily inferior to the Red Army, would have some chances of success.[37] Hitler believed he could split the Allied forces and compel the Americans and British to settle for a separate peace, independent of the Soviet Union.[38] Success in the west would give the Germans time to design and produce more advanced weapons (such as jet aircraft, new U-boat designs and super-heavy tanks) and permit the concentration of forces in the east. After the war ended, this assessment was generally viewed as unrealistic, given Allied air superiority throughout Europe and their ability to continually disrupt German offensive operations.[39]

Given the reduced manpower of their land forces at the time, the Germans believed the best way to seize the initiative would be to attack in the West against the smaller Allied forces rather than against the vast Soviet armies. Even the encirclement and destruction of multiple Soviet armies like in 1941, would still have left the Soviets with a numerical superiority.

Several senior German military officers, including Field Marshals Walter Model and Gerd von Rundstedt, expressed concern as to whether the goals of the offensive could be realized. They offered alternative plans, but Hitler would not listen. The plan banked on unfavorable weather, including heavy fog and low-lying clouds, which would minimize the Allied air advantage.[40] Hitler originally set the offensive for late November, before the anticipated start of the Russian winter offensive.

In the west supply problems began significantly to impede Allied operations, even though the opening of the port of Antwerp in late November improved the situation somewhat. The positions of the Allied armies stretched from southern France all the way north to the Netherlands. German planning for the counteroffensive rested on the premise that a successful strike against thinly-manned stretches of the line would halt Allied advances on the entire Western Front.

Model and von Rundstedt both believed aiming for Antwerp was too ambitious, given Germany's scarce resources in late 1944. At the same time, they felt that maintaining a purely defensive posture (as had been the case since Normandy) would only delay defeat, not avert it. They thus developed alternative, less ambitious plans that did not aim to cross the Meuse River (in German and Dutch: Maas); Model's being Unternehmen Herbstnebel (Operation Autumn Mist) and von Rundstedt's Fall Martin ("Plan Martin"). The two field marshals combined their plans to present a joint "small solution" to Hitler.[lower-alpha 11][lower-alpha 12] A second plan called for a classic Blitzkrieg attack through the weakly defended Ardennes—mirroring the successful German offensive there during the Battle of France in 1940—aimed at splitting the armies along the U.S.—British lines and capturing Antwerp.

Hitler chose the second plan, believing a successful encirclement would have little impact on the overall situation and finding the prospect of splitting the Anglo-American armies more appealing. The disputes between Montgomery and Bradley were well known, and Hitler hoped he could exploit this disunity. If the attack were to succeed in capturing Antwerp, four complete armies would be trapped without supplies behind German lines. Both plans centered on attacks against the American forces.

Tasked with carrying out the operation were Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Walther Model, the commander of German Army Group B (Heeresgruppe B), and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the overall commander of the German Army Command in the West, who had moved his base of operations to Kransberg Castle.

Operation names

The Wehrmacht's code name for the offensive was Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein ("Operation Watch on the Rhine"), after the German patriotic hymn Die Wacht am Rhein, a name that deceptively implied the Germans would be adopting a defensive posture along the Western Front. The Germans also referred to it as "Ardennenoffensive" (Ardennes Offensive) and Rundstedt-Offensive, both names being generally used nowadays in modern Germany. The French (and Belgian) name for the operation is Bataille des Ardennes (Battle of the Ardennes). The battle was militarily defined by the Allies as the Ardennes Counteroffensive, which included the German drive and the American effort to contain and later defeat it. The phrase Battle of the Bulge was coined by contemporary press to describe the way the Allied front line bulged inward on wartime news maps.[23][24]

While the Ardennes Counteroffensive is the correct term in Allied military language, the official Ardennes-Alsace campaign reached beyond the Ardennes battle region, and the most popular description in English speaking countries remains simply the Battle of the Bulge.

Planning

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The OKW (High Command of the German Armed Forces) decided by mid-September, at Hitler's insistence, that the offensive would be mounted in the Ardennes, as was done in 1940. Many German generals objected, but the offensive was planned and carried out anyway. In 1940 German forces had passed through the Ardennes in three days before engaging the enemy, but the 1944 plan called for battle in the forest itself. The main forces were to advance westward to the Meuse River, then turn northwest for Antwerp and Brussels. The close terrain of the Ardennes would make rapid movement difficult, though open ground beyond the Meuse offered the prospect of a successful dash to the coast.

Four armies were selected for the operation. First was the Sixth Panzer Army, under SS SS-Oberstgruppenführer Sepp Dietrich. It had been created on 26 October 1944 and incorporated the most senior and the experienced formation of the Waffen-SS: the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler as well as the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. The 6th Panzer Army was designated the northernmost attack force, having its northernmost point on the pre-attack battlefront nearest the German town of Monschau. It was entrusted with the offensive's primary objective—capturing Antwerp.

The Fifth Panzer Army under General Hasso von Manteuffel was assigned to the middle attack route with the objective of capturing Brussels.

The Seventh Army, under General Erich Brandenberger, was assigned to the southernmost attack, having its southernmost point on the pre-attack battlefront nearest the Luxembourgish city of Echternach, with the task of protecting the flank. This Army was made up of only four infantry divisions, with no large-scale armored formations to use as a spearhead unit. As a result, they made little progress throughout the battle.

Also participating in a secondary role was the Fifteenth Army, under General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen. Recently brought back up to strength and re-equipped after heavy fighting during Market Garden, it was located on the far north of the Ardennes battlefield and tasked with holding U.S. forces in place, with the possibility of launching its own attack given favorable conditions.

For the offensive to be successful, four criteria were deemed critical: the attack had to be a complete surprise; the weather conditions had to be poor to neutralize Allied air superiority and the damage it could inflict on the German offensive and its supply lines;[41] the progress had to be rapid—the Meuse River, halfway to Antwerp, had to be reached by day 4; and Allied fuel supplies would have to be captured intact along the way because the combined Wehrmacht forces were short on fuel. The General Staff estimated they only had enough fuel to cover one-third to one-half of the ground to Antwerp in heavy combat conditions.

The plan originally called for just under 45 divisions, including a dozen panzer and panzergrenadier divisions forming the armored spearhead and various infantry units to form a defensive line as the battle unfolded. By this time, however, the German Army suffered from an acute manpower shortage, and the force had been reduced to around 30 divisions. Although it retained most of its armor, there were not enough infantry units because of the defensive needs in the East. These 30 newly rebuilt divisions used some of the last reserves of the German Army. Among them were Volksgrenadier ("People's Grenadier") units formed from a mix of battle-hardened veterans and recruits formerly regarded as too young, too old or too frail to fight. Training time, equipment and supplies were inadequate during the preparations. German fuel supplies were precarious—those materials and supplies that could not be directly transported by rail had to be horse-drawn to conserve fuel, and the mechanized and panzer divisions would depend heavily on captured fuel. As a result, the start of the offensive was delayed from 27 November to 16 December.

Before the offensive the Allies were virtually blind to German troop movement. During the liberation of France, the extensive network of the French resistance had provided valuable intelligence about German dispositions. Once they reached the German border, this source dried up. In France, orders had been relayed within the German army using radio messages enciphered by the Enigma machine, and these could be picked up and decrypted by Allied code-breakers headquartered at Bletchley Park, to give the intelligence known as Ultra. In Germany such orders were typically transmitted using telephone and teleprinter, and a special radio silence order was imposed on all matters concerning the upcoming offensive.[42] The major crackdown in the Wehrmacht after the 20 July plot to assassinate Hitler resulted in much tighter security and fewer leaks. The foggy autumn weather also prevented Allied reconnaissance aircraft from correctly assessing the ground situation. German units assembling in the area were even issued charcoal instead of wood for cooking fires to cut down on smoke and reduce chances of Allied observers deducing a troop buildup was underway. [43]

For these reasons Allied High Command considered the Ardennes a quiet sector, relying on assessments from their intelligence services that the Germans were unable to launch any major offensive operations this late in the war. What little intelligence they had led the Allies to believe precisely what the Germans wanted them to believe-–that preparations were being carried out only for defensive, not offensive, operations. The Allies relied too much on Ultra, not human reconnaissance. In fact, because of the Germans' efforts, the Allies were led to believe that a new defensive army was being formed around Düsseldorf in the northern Rhineland, possibly to defend against British attack. This was done by increasing the number of flak (Flugabwehrkanonen, i.e. anti-aircraft cannons) in the area and the artificial multiplication of radio transmissions in the area. The Allies at this point thought the information was of no importance. All of this meant that the attack, when it came, completely surprised the Allied forces. Remarkably, the U.S. Third Army intelligence chief, Colonel Oscar Koch, the U.S. First Army intelligence chief and the SHAEF intelligence officer Brigadier General Kenneth Strong all correctly predicted the German offensive capability and intention to strike the U.S. VIII Corps area. These predictions were largely dismissed by the U.S. 12th Army Group.[44] Strong had informed Bedell Smith in December of his suspicions. Bedell Smith sent Strong to warn Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, the commander of the 12th Army Group, of the danger. Bradley's response was succinct: "Let them come."[45]:362–366 Historian Patrick K. O'Donnell writes that on 8 December 1944, U.S. Rangers at great cost took Hill 400 during the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest. The next day GIs who relieved the Rangers reported a considerable movement of German troops inside the Ardennes in the enemy's rear, but that no one in the chain of command connected the dots.[46]

Because the Ardennes was considered a quiet sector, economy-of-force considerations led it to be used as a training ground for new units and a rest area for units that had seen hard fighting. The U.S. units deployed in the Ardennes thus were a mixture of inexperienced troops (such as the raw U.S. 99th and 106th "Golden Lions" Divisions), and battle-hardened troops sent to that sector to recuperate (the 28th Infantry Division).

Two major special operations were planned for the offensive. By October it was decided that Otto Skorzeny, the German SS-commando who had rescued the former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, was to lead a task force of English-speaking German soldiers in "Operation Greif". These soldiers were to be dressed in American and British uniforms and wear dog tags taken from corpses and POWs. Their job was to go behind American lines and change signposts, misdirect traffic, generally cause disruption and seize bridges across the Meuse River between Liège and Namur. By late November, another ambitious special operation was added: Col. Friedrich August von der Heydte was to lead a Fallschirmjäger-Kampfgruppe (paratrooper combat group) in Operation Stösser, a night-time paratroop drop behind the Allied lines aimed at capturing a vital road junction near Malmedy.[47][48]

German intelligence had set 20 December as the expected date for the start of the upcoming Soviet offensive, aimed at crushing what was left of German resistance on the Eastern Front and thereby opening the way to Berlin. It was hoped that Soviet leader Stalin would delay the start of the operation once the German assault in the Ardennes had begun and wait for the outcome before continuing.

After the 20 July plot attempt on Hitler's life, and the close advance of the Red Army which would seize the site on 27 January 1945, Hitler and his staff had been forced to abandon the Wolfsschanze headquarters in East Prussia, in which they had coordinated much of the fighting on the Eastern Front. After a brief visit to Berlin, Hitler travelled on his Führersonderzug ("Special Train of the Führer" (Leader)) to Giessen on 11 December, taking up residence in the Adlerhorst (eyrie) command complex, co-located with OB West's base at Kransberg Castle. Believing in omens and the successes of his early war campaigns that had been planned at Kransberg, Hitler had chosen the site from which he had overseen the successful 1940 campaign against France and the Low Countries.

Von Rundstedt set up his operational headquarters near Limburg, close enough for the generals and Panzer Corps commanders who were to lead the attack to visit Adlerhorst on 11 December, travelling there in an SS-operated bus convoy. With the castle acting as overflow accommodation, the main party was settled into the Adlerhorst's Haus 2 command bunker, including Gen. Alfred Jodl, Gen. Wilhelm Keitel, Gen. Blumentritt, von Manteuffel and SS Gen. Joseph ("Sepp") Dietrich. Von Rundstedt then ran through the battle plan, while Hitler made one of his endless speeches.

In a personal conversation on 13 December between Walther Model and Friedrich von der Heydte, who was put in charge of Operation Stösser, von der Heydte gave Operation Stösser less than a 10% chance of succeeding. Model told him it was necessary to make the attempt: "It must be done because this offensive is the last chance to conclude the war favorably."[49]

Initial German assault

On 16 December 1944, at 05:30, the Germans began the assault with a massive, 90-minute artillery barrage using 1,600 artillery pieces[50] across a 130-kilometre (80 mi) front on the Allied troops facing the 6th Panzer Army. The Americans' initial impression was that this was the anticipated, localized counterattack resulting from the Allies' recent attack in the Wahlerscheid sector to the north, where the 2nd Division had knocked a sizable dent in the Siegfried Line. Heavy snowstorms engulfed parts of the Ardennes area. While having the effect of keeping the Allied aircraft grounded, the weather also proved troublesome for the Germans because poor road conditions hampered their advance. Poor traffic control led to massive traffic jams and fuel shortages in forward units.

In the center, von Manteuffel's Fifth Panzer Army attacked towards Bastogne and St. Vith, both road junctions of great strategic importance. In the south, Brandenberger's Seventh Army pushed towards Luxembourg in its efforts to secure the flank from Allied attacks. Only one month before 250 members of the Waffen-SS had unsuccessfully tried to recapture the town of Vianden with its castle from the Luxembourgish resistance during the Battle of Vianden.

Attack on the northern shoulder

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

While the Siege of Bastogne is often credited as the central point where the German offensive was stopped,[51] the battle for Elsenborn Ridge was actually the decisive component of the Battle of the Bulge, stopping the advance of the best equipped armored units of the German army and forcing them to use unfavorable routes that considerably slowed their advance.[52][53]

Best German divisions assigned

The attack on Monschau, Höfen, Krinkelt-Rocherath, and then Elsenborn Ridge was led by the units personally selected by Adolf Hitler. The 6th Panzer Army was given priority for supply and equipment and were assigned the shortest route to the ultimate objective of the offensive, Antwerp.[53] The 6th Panzer Army included the elite of the Waffen-SS, including four Panzer divisions and five infantry divisions in three corps.[54][55] SS Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper led Kampfgruppe Peiper, consisting of 4,800 men and 600 vehicles, which was charged with leading the main effort. However, its newest and most powerful tank, the Tiger II heavy tank, consumed 1 gallon of fuel to go half a mile, and the Germans had less than half the fuel they needed to reach Antwerp.[3]:age needed

German forces held up

The attacks by the Sixth Panzer Army's infantry units in the north fared badly because of unexpectedly fierce resistance by the U.S. 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions. Kampfgruppe Peiper, at the head of the SS Oberstgruppenführer Sepp Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army, had been designated to take the Losheim-Losheimergraben road, a key route through the Losheim Gap, but it was closed by two collapsed overpasses that German engineers failed to repair during the first day.[56] Peiper's forces were rerouted through Lanzerath, where on the first day, an entire German battalion of 500 men was held up for 10 hours at the small village of Lanzerath.

To preserve the quantity of armor available, the infantry of the 9th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment, 3rd Fallschirmjaeger Division, had been ordered to clear the village first. A single 18-man Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon from the 99th Infantry Division along with four Forward Air Controllers held up the battalion of about 500 German paratroopers until sunset, about 16:00, causing 92 casualties among the Germans.

This created a bottleneck in the German advance. Kampfgruppe Peiper did not begin his advance until nearly 16:00, more than 16 hours behind schedule and didn't reach Bucholz Station until the early morning of 17 December. Their intention was to control the twin villages of Rocherath-Krinkelt which would clear a path to the high ground of Elsenborn Ridge. Occupation of this dominating terrain would allow control of the roads to the south and west and ensure supply to Kampfgruppe Peiper's armored task force.

Malmedy massacre

At 12:30 on 17 December, Kampfgruppe Peiper was near the hamlet of Baugnez, on the height halfway between the town of Malmedy and Ligneuville, when they encountered elements of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, U.S. 7th Armored Division.[57][58] After a brief battle the lightly armed Americans surrendered. They were disarmed and, with some other Americans captured earlier (approximately 150 men), sent to stand in a field near the crossroads under light guard. About fifteen minutes after Peiper's advance guard passed through, the main body under the command of SS Sturmbannführer Werner Pötschke arrived. Allegedly, the SS troopers suddenly opened fire on the prisoners. As soon as the firing began, the prisoners panicked. Most were shot where they stood, though some managed to flee. Accounts of the killing vary, but 84 of the POWs were murdered. A few survived, and news of the killings of prisoners of war raced through Allied lines.[58] Following the end of the war, soldiers and officers of Kampfgruppe Peiper, including Joachim Peiper and SS general Sepp Dietrich, were tried for the incident at the Malmedy massacre trial.[59]

Kampfgruppe Peiper deflected southeast

Driving to the south-east of Elsenborn, Kampfgruppe Peiper entered Honsfeld, where they encountered one of the 99th Division's rest centers, clogged with confused American troops. They quickly captured portions of the 3rd Battalion of the 394th Infantry Regiment. They destroyed a number of American armored units and vehicles, and took several dozen prisoners who were subsequently murdered.[60][57][61] Peiper also captured 50,000 US gallons (190,000 l; 42,000 imp gal) of fuel for his vehicles.[62]

Peiper then advanced north-west towards Büllingen, keeping to the plan to move west, unaware that if he had turned north he had an opportunity to flank and trap the entire 2nd and 99th Divisions.[63] Instead, intent on driving west, Peiper turned south to detour around Hünningen, choosing a route designated Rollbahn D as he had been given latitude to choose the best route west.[64]

To the north, the 277th Volksgrenadier Division attempted to break through the defending line of the U.S. 99th and the 2nd Infantry Divisions. The 12th SS Panzer Division, reinforced by additional infantry (Panzergrenadier and Volksgrenadier) divisions, took the key road junction at Losheimergraben just north of Lanzerath and attacked the twin villages of Rocherath and Krinkelt.

Wereth 11

Another, smaller massacre was committed in Wereth, Belgium, approximately 6.5 miles (10.5 km) northeast of Saint-Vith, on 17 December 1944. Eleven black American soldiers were tortured after surrendering and then shot by men of the 1st SS Panzer Division belonging to Kampfgruppe Knittel. The perpetrators were never punished for this crime and recent research indicates that men from Third Company of the Reconnaissance Battalion were responsible.[65][66]

Germans advance west

By the evening the spearhead had pushed north to engage the U.S. 99th Infantry Division and Kampfgruppe Peiper arrived in front of Stavelot. Peiper's forces was already behind his timetable because of the stiff American resistance and because when the Americans fell back, their engineers blew up bridges and emptied fuel dumps. Peiper's unit was delayed and his vehicles denied critically needed fuel. They took 36 hours to advance from the Eifel region to Stavelot, while the same advance had taken just nine hours in 1940.

Kampfgruppe Peiper attacked Stavelot on 18 December but was unable to capture the town before the Americans evacuated a large fuel depot.[68] Three tanks attempted to take the bridge, but the lead vehicle was disabled by a mine. Following this, 60 grenadiers advanced forward but were stopped by concentrated American defensive fire. After a fierce tank battle the next day, the Germans finally entered the town when U.S. engineers failed to blow the bridge.

Capitalizing on his success and not wanting to lose more time, Peiper rushed an advance group toward the vital bridge at Trois-Ponts, leaving the bulk of his strength in Stavelot. When they reached it at 11:30 on 18 December, retreating U.S. engineers blew it up.[69][70] Peiper detoured north towards the villages of La Gleize and Cheneux. At Cheneux, the advance guard was attacked by American fighter-bombers, destroying two tanks and five halftracks, blocking the narrow road. The group got moving again at dusk at 16:00 and was able to return to its original route at around 18:00. Of the two bridges now remaining between Kampfgruppe Peiper and the Meuse, the bridge over the Lienne was blown by the Americans as the Germans approached. Peiper turned north and halted his forces in the woods between La Gleize and Stoumont.[71] He learned that Stoumont was strongly held and that the Americans were bringing up strong reinforcements from Spa.

To Peiper's south, the advance of Kampfgruppe Hansen had stalled. SS Oberführer Mohnke ordered Schnellgruppe Knittel, which had been designated to follow Hansen, to instead move forward to support Peiper. SS Sturmbannführer Knittel crossed the bridge at Stavelot around 19:00 against American forces trying to retake the town. Knittel pressed forward towards La Gleize, and shortly afterward the Americans recaptured Stavelot. Peiper and Knittel both faced the prospect of being cut off.[71]

German advance halted

At dawn on 19 December, Peiper surprised the American defenders of Stoumont by sending infantry from the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment in an attack and a company of Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) to infiltrate their lines. He followed this with a Panzer attack, gaining the eastern edge of the town. An American tank battalion arrived but, after a two-hour tank battle, Peiper finally captured Stoumont at 10:30. Knittel joined up with Peiper and reported the Americans had recaptured Stavelot to their east.[72] Peiper ordered Knittel to retake Stavelot. Assessing his own situation, he determined that his Kampfgruppe did not have sufficient fuel to cross the bridge west of Stoumont and continue his advance. He maintained his lines west of Stoumont for a while, until the evening of 19 December when he withdrew them to the village edge. On the same evening the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division under Maj. Gen. James Gavin arrived and deployed at La Gleize and along Peiper's planned route of advance.[72]

German efforts to reinforce Peiper were unsuccessful. Kampfgruppe Hansen was still struggling against bad road conditions and stiff American resistance on the southern route. Schnellgruppe Knittel was forced to disengage from the heights around Stavelot. Kampfgruppe Sandig, which had been ordered to take Stavelot, launched another attack without success. Sixth Panzer Army commander SS-Oberstgruppenführer Sepp Dietrich ordered Hermann Prieß, commanding officer of the I SS Panzer Corps, to increase its efforts to back Peiper's Kampfgruppe, but Prieß was unable to break through.[73]

Small units of the U.S. 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, attacked the dispersed units of Kampfgruppe Peiper on the morning of 21 December. They failed and were forced to withdraw, and a number were captured, including battalion commander Maj. Hal McCown. Peiper learned that his reinforcements had been directed to gather in La Gleize to his east, and he withdrew, leaving wounded Americans and Germans in the Froidcourt Castle. As he withdrew from Cheneux, American paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division engaged the Germans in fierce house-to-house fighting. The Americans shelled Kampfgruppe Peiper on 22 December, and although the Germans had run out of food and had virtually no fuel, they continued to fight. A Luftwaffe resupply mission went badly when SS-Brigadeführer (Brigadier Gen.) Wilhelm Mohnke insisted the grid coordinates supplied by Peiper were wrong, parachuting supplies into American hands in Stoumont.[74]

In La Gleize, Peiper set up defenses waiting for German relief. When the relief force was unable to penetrate the Allied lines, he decided to break through the Allied lines and return to the German lines on 23 December. The men of the Kampfgruppe were forced to abandon their vehicles and heavy equipment, although most of the 800 remaining troops were able to escape.[75]

Outcome

The 99th Infantry Division as a whole, outnumbered five to one, inflicted casualties in the ratio of eighteen to one. The division lost about 20% of its effective strength, including 465 killed and 2,524 evacuated due to wounds, injuries, fatigue, or trench foot. German losses were much higher. In the northern sector opposite the 99th, this included more than 4,000 deaths and the destruction of 60 tanks and big guns.[76] Historian John S.D. Eisenhower wrote, "... the action of the 2nd and 99th Divisions on the northern shoulder could be considered the most decisive of the Ardennes campaign."[77][78]

The stiff American defense prevented the Germans from reaching the vast array of supplies near the Belgian cities of Liège and Spa and the road network west of the Elsenborn Ridge leading to the Meuse River.[79] After more than ten days of intense battle, they pushed the Americans out of the villages, but were unable to dislodge them from the ridge, where elements of the V Corps of the First U.S. Army prevented the German forces from reaching the road network to their west.

Operation Stösser

Operation Stösser was a paratroop drop into the American rear in the High Fens (French: Hautes Fagnes; German: Hohes Venn; Dutch: Hoge Venen) area. The objective was the "Baraque Michel" crossroads. It was led by Oberst Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte, considered by Germans to be a hero of the Battle of Crete.[80]

It was the German paratroopers' only night time drop during World War II. Von der Heydte was given only eight days to prepare prior to the assault. He was not allowed to use his own regiment because their movement might alert the Allies to the impending counterattack. Instead, he was provided with a Kampfgruppe of 800 men. The II Parachute Corps was tasked with contributing 100 men from each of its regiments. In loyalty to their commander, 150 men from von der Heydte's own unit, the 6th Parachute Regiment, went against orders and joined him.[81] They had little time to establish any unit cohesion or train together.

The parachute drop was a complete failure. Von der Heydte ended up with a total of around 300 troops. Too small and too weak to counter the Allies, they abandoned plans to take the crossroads and instead converted his mission to reconnaissance. With only enough ammunition for a single fight, they withdrew towards Germany and attacked the rear of the American lines. Only about 100 of his weary men finally reached the German rear.[82]

Chenogne massacre

Following the Malmedy massacre, on New Year's Day 1945, after having previously received orders to take no prisoners,[83] American soldiers allegedly shot approximately sixty German prisoners of war near the Belgian village of Chenogne (8 km from Bastogne).[84]

Attack in the center

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Germans fared better in the center (the 32 km (20 mi) Schnee Eifel sector) as the Fifth Panzer Army attacked positions held by the U.S. 28th and 106th Infantry Divisions. The Germans lacked the overwhelming strength that had been deployed in the north, but still possessed a marked numerical and material superiority over the very thinly spread 28th and 106th divisions. They succeeded in surrounding two largely intact regiments (422nd and 423rd) of the 106th Division in a pincer movement and forced their surrender, a tribute to the way Manteuffel's new tactics had been applied.[85] The official U.S. Army history states: "At least seven thousand [men] were lost here and the figure probably is closer to eight or nine thousand. The amount lost in arms and equipment, of course, was very substantial. The Schnee Eifel battle, therefore, represents the most serious reverse suffered by American arms during the operations of 1944–45 in the European theater."[3]:170

Battle for St. Vith

In the center the town of St. Vith, a vital road junction, presented the main challenge for both von Manteuffel's and Dietrich's forces. The defenders, led by the 7th Armored Division, included the remaining regiment of the 106th U.S. Infantry Division, with elements of the 9th Armored Division and 28th U.S. Infantry Division. These units, which operated under the command of Generals Robert W. Hasbrouck (7th Armored) and Alan W. Jones (106th Infantry), successfully resisted the German attacks, significantly slowing the German advance. At Montgomery's orders, St. Vith was evacuated on 21 December; U.S. troops fell back to entrenched positions in the area, presenting an imposing obstacle to a successful German advance. By 23 December, as the Germans shattered their flanks, the defenders' position became untenable and U.S. troops were ordered to retreat west of the Salm River. Since the German plan called for the capture of St. Vith by 18:00 on 17 December, the prolonged action in and around it dealt a major setback to their timetable.[3]:407

Meuse River bridges

To protect the river crossings on the Meuse at Givet, Dinant and Namur, Montgomery ordered those few units available to hold the bridges on 19 December. This led to a hastily assembled force including rear-echelon troops, military police and Army Air Force personnel. The British 29th Armoured Brigade of British 11th Armored Division, which had turned in its tanks for re-equipping, was told to take back their tanks and head to the area. British XXX Corps was significantly reinforced for this effort. Units of the corps which fought in the Ardennes were the 51st (Highland) and 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Divisions, the British 6th Airborne Division, the 29th and 33rd Armored Brigades, and the 34th Tank Brigade.[86]

Unlike the Germans forces on the northern and southern shoulders who were experiencing great difficulties, the German advance in the center gained considerable ground. The Fifth Panzer Army was spearheaded by the 2nd Panzer Division while the Panzer-Lehrdivision (Armored Training Division) came up from the south, leaving Bastogne to other units. The Ourthe River was passed at Ourtheville on 21 December. Lack of fuel held up the advance for one day, but on 23 December the offensive was resumed towards the two small towns of Hargimont and Marche-en-Famenne. Hargimont was captured the same day, but Marche-en-Famenne was strongly defended by the American 84th Division. Gen. von Lüttwitz, commander of the XXXXVII Panzer-Korps, ordered the Division to turn westwards towards Dinant and the Meuse, leaving only a blocking force at Marche-en-Famenne. Although advancing only in a narrow corridor, 2nd Panzer Division was still making rapid headway, leading to jubilation in Berlin. Headquarters now freed up the 9th Panzer Division for Fifth Panzer Army, which was deployed at Marche.[87]

On 22/23 December German forces reached the woods of Foy-Nôtre-Dame, only a few kilometers ahead of Dinant. However, the narrow corridor caused considerable difficulties, as constant flanking attacks threatened the division. On 24 December, German forces made their furthest penetration west. The Panzer-Lehrdivision took the town of Celles, while a bit farther north, parts of 2nd Panzer Division were in sight of the Meuse near Dinant at Foy-Nôtre-Dame. A hastily assembled Allied blocking force on the east side of the river, however, prevented the German probing forces from approaching the Dinant bridge. By late Christmas Eve the advance in this sector was stopped, as Allied forces threatened the narrow corridor held by the 2nd Panzer Division.[87]

Operation Greif and Operation Währung

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

For Operation Greif ("Griffin"), Otto Skorzeny successfully infiltrated a small part of his battalion of English-speaking Germans disguised in American uniforms behind the Allied lines. Although they failed to take the vital bridges over the Meuse, their presence caused confusion out of all proportion to their military activities, and rumors spread quickly.[39] Even General George Patton was alarmed and, on 17 December, described the situation to General Dwight Eisenhower as "Krauts…speaking perfect English…raising hell, cutting wires, turning road signs around, spooking whole divisions, and shoving a bulge into our defenses."

Checkpoints were set up all over the Allied rear, greatly slowing the movement of soldiers and equipment. American MPs at these checkpoints grilled troops on things that every American was expected to know, like the identity of Mickey Mouse's girlfriend, baseball scores, or the capital of a particular U.S. state—though many could not remember or did not know. General Omar Bradley was briefly detained when he correctly identified Springfield as the capital of Illinois because the American MP who questioned him mistakenly believed the capital was Chicago.[39][88]

The tightened security nonetheless made things very hard for the German infiltrators, and a number of them were captured. Even during interrogation, they continued their goal of spreading disinformation; when asked about their mission, some of them claimed they had been told to go to Paris to either kill or capture General Dwight Eisenhower.[40] Security around the general was greatly increased, and Eisenhower was confined to his headquarters. Because Skorzeny's men were captured in American uniforms, they were executed as spies.[39][89] This was the standard practice of every army at the time, as many belligerents considered it necessary to protect their territory against the grave dangers of enemy spying.[90] Skorzeny said that he was told by German legal experts that as long he did not order his men to fight in combat while wearing American uniforms, such a tactic was a legitimate ruse of war.[91] Skorzeny and his men were fully aware of their likely fate, and most wore their German uniforms underneath their American ones in case of capture. Skorzeny was tried by an American military tribunal in 1947 at the Dachau Trials for allegedly violating the laws of war stemming from his leadership of Operation Greif, but was acquitted. He later moved to Spain and South America.[39]

In Operation Währung ("operation currency"), a small number of German agents infiltrated Allied lines in American uniforms. These agents were then to use an existing Nazi intelligence network to attempt to bribe rail and port workers to disrupt Allied supply operations. However, this operation was a failure.

Attack in the south

Further south on Manteuffel's front, the main thrust was delivered by all attacking divisions crossing the River Our, then increasing the pressure on the key road centers of St. Vith and Bastogne. The more experienced 28th Infantry Division put up a much more dogged defense than the inexperienced soldiers of the 106th Infantry Division. The 112th Infantry Regiment (the most northerly of the 28th Division's regiments), holding a continuous front east of the Our, kept German troops from seizing and using the Our River bridges around Ouren for two days, before withdrawing progressively westwards.

The 109th and 110th Regiments of the 28th Division, however, fared worse, as they were spread so thinly that their positions were easily bypassed. Both offered stubborn resistance in the face of superior forces and threw the German schedule off by several days. The 110th's situation was by far the worst, as it was responsible for an 18-kilometre (11 mi) front while its 2nd Battalion was withheld as the divisional reserve. Panzer columns took the outlying villages and widely separated strongpoints in bitter fighting, and advanced to points near Bastogne within four days. The struggle for the villages and American strongpoints, plus transport confusion on the German side, slowed the attack sufficiently to allow the 101st Airborne Division (reinforced by elements from the 9th and 10th Armored Divisions) to reach Bastogne by truck on the morning of 19 December. The fierce defense of Bastogne, in which American paratroopers particularly distinguished themselves, made it impossible for the Germans to take the town with its important road junctions. The panzer columns swung past on either side, cutting off Bastogne on 20 December but failing to secure the vital crossroads.

In the extreme south, Brandenberger's three infantry divisions were checked by divisions of the U.S. VIII Corps after an advance of 6.4 km (4 mi); that front was then firmly held. Only the 5th Parachute Division of Brandenberger's command was able to thrust forward 19 km (12 mi) on the inner flank to partially fulfill its assigned role. Eisenhower and his principal commanders realized by 17 December that the fighting in the Ardennes was a major offensive and not a local counterattack, and they ordered vast reinforcements to the area. Within a week 250,000 troops had been sent. General Gavin of the 82nd Airborne Division arrived on the scene first and ordered the 101st to hold Bastogne while the 82nd would take the more difficult task of facing the SS Panzer Divisions; it was also thrown into the battle north of the bulge, near Elsenborn Ridge.

Siege of Bastogne

By the time the senior Allied commanders met in a bunker in Verdun on 19 December, the town of Bastogne and its network of 11 hard-topped roads leading through the widely forested mountainous terrain with deep river valleys and boggy mud of the Ardennes region were to have been in German hands for several days. By the time of that meeting, two separate westbound German columns that were to have bypassed the town to the south and north, the 2nd Panzer Division and Panzer-Lehr-Division of XLVII Panzer Corps, as well as the Corps' infantry (26th Volksgrenadier Division), coming due west had been engaged and much slowed and frustrated in outlying battles at defensive positions up to sixteen kilometres (10 mi) from the town proper—and were gradually being forced back onto and into the hasty defenses built within the municipality. Moreover, the sole corridor that was open (to the southeast) was threatened and it had been sporadically closed as the front shifted, and there was expectation that it would be completely closed sooner than later, given the strong likelihood that the town would soon be surrounded.

Gen. Eisenhower, realizing that the Allies could destroy German forces much more easily when they were out in the open and on the offensive than if they were on the defensive, told his generals, "The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster. There will be only cheerful faces at this table." Patton, realizing what Eisenhower implied, responded, "Hell, let's have the guts to let the bastards go all the way to Paris. Then, we'll really cut 'em off and chew 'em up." Eisenhower, after saying he was not that optimistic, asked Patton how long it would take to turn his Third Army, located in northeastern France, north to counterattack. To the disbelief of the other generals present, Patton replied that he could attack with two divisions within 48 hours. Unknown to the other officers present, before he left Patton had ordered his staff to prepare three contingency plans for a northward turn in at least corps strength. By the time Eisenhower asked him how long it would take, the movement was already underway.[92] On 20 December, Eisenhower removed the First and Ninth U.S. Armies from Gen. Bradley's 12th Army Group and placed them under Montgomery's 21st Army Group.[93]

By 21 December the Germans had surrounded Bastogne, which was defended by the 101st Airborne Division, the all African American 969th Artillery Battalion, and Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division. Conditions inside the perimeter were tough—most of the medical supplies and medical personnel had been captured. Food was scarce, and by 22 December artillery ammunition was restricted to 10 rounds per gun per day. The weather cleared the next day, however, and supplies (primarily ammunition) were dropped over four of the next five days.[94]

Despite determined German attacks, however, the perimeter held. The German commander, Generalleutnant (Lt. Gen.) Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz,[95] requested Bastogne's surrender.[96] When Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st, was told of the Nazi demand to surrender, in frustration he responded, "Nuts!" After turning to other pressing issues, his staff reminded him that they should reply to the German demand. One officer, Lt. Col. Harry Kinnard, noted that McAuliffe's initial reply would be "tough to beat." Thus McAuliffe wrote on the paper, which was typed up and delivered to the Germans, the line he made famous and a morale booster to his troops: "NUTS!"[97] That reply had to be explained, both to the Germans and to non-American Allies.[lower-alpha 13]

Both 2nd Panzer and Panzer-Lehrdivision moved forward from Bastogne after 21 December, leaving only Panzer-Lehrdivision's 901st Regiment to assist the 26th Volksgrenadier-Division in attempting to capture the crossroads. The 26th VG received one Panzergrenadier Regiment from the 15th Panzergrenadier Division on Christmas Eve for its main assault the next day. Because it lacked sufficient troops and those of the 26th VG Division were near exhaustion, the XLVII Panzerkorps concentrated its assault on several individual locations on the west side of the perimeter in sequence rather than launching one simultaneous attack on all sides. The assault, despite initial success by its tanks in penetrating the American line, was defeated and all the tanks destroyed. The next day, 26 December, the spearhead of Gen. Patton's 4th Armored Division broke through and opened a corridor to Bastogne.[94]

Allied counteroffensive

On 23 December, the weather conditions started improving, allowing the Allied air forces to attack. They launched devastating bombing raids on the German supply points in their rear, and P-47 Thunderbolts started attacking the German troops on the roads. Allied air forces also helped the defenders of Bastogne, dropping much-needed supplies—medicine, food, blankets, and ammunition. A team of volunteer surgeons flew in by military glider and began operating in a tool room.[98]

By 24 December, the German advance was effectively stalled short of the Meuse. Units of the British XXX Corps were holding the bridges at Dinant, Givet, and Namur and U.S. units were about to take over. The Germans had outrun their supply lines, and shortages of fuel and ammunition were becoming critical. Up to this point the German losses had been light, notably in armor, which was almost untouched with the exception of Peiper's losses. On the evening of 24 December, General Hasso von Manteuffel recommended to Hitler's Military Adjutant a halt to all offensive operations and a withdrawal back to the Westwall (literally Western Rampart). Hitler rejected this.

However, disagreement and confusion at the Allied command prevented a strong response, throwing away the opportunity for a decisive action. In the center, on Christmas Eve, the 2nd Armored Division attempted to attack and cut off the spearheads of the 2nd Panzer Division at the Meuse, while the units from the 4th Cavalry Group kept the 9th Panzer Division at Marche busy. As result, parts of the 2nd Panzer Division were cut off. The Panzer-Lehr division tried to relieve them, but was only partially successful, as the perimeter held. For the next two days the perimeter was strengthened. On 26 and 27 December the trapped units of 2nd Panzer Division made two break-out attempts, again only with partial success, as major quantities of equipment fell into Allied hands. Further Allied pressure out of Marche finally led the German command to the conclusion that no further offensive action towards the Meuse was possible.[99]

In the south, Patton's Third Army was battling to relieve Bastogne. At 16:50 on 26 December, the lead element, Company D, 37th Tank Battalion of the 4th Armored Division, reached Bastogne, ending the siege.

German counterattack

On 1 January, in an attempt to keep the offensive going, the Germans launched two new operations. At 09:15, the Luftwaffe launched Unternehmen Bodenplatte (Operation Baseplate, literally Operation Floor Panel), a major campaign against Allied airfields in the Low Countries, which are nowadays called the Benelux States. Hundreds of planes attacked Allied airfields, destroying or severely damaging some 465 aircraft. However, the Luftwaffe lost 277 planes, 62 to Allied fighters and 172 mostly because of an unexpectedly high number of Allied flak guns, set up to protect against German V-1 flying bomb/missile attacks and using proximity fused shells, but also by friendly fire from the German flak guns that were uninformed of the pending large-scale German air operation. The Germans suffered heavy losses at an airfield named Y-29, losing 24 of their own planes while downing only one American plane. While the Allies recovered from their losses in just days, the operation left the Luftwaffe weak and ineffective for the remainder of the war.[100]

On the same day, German Army Group G (Heeresgruppe G) and Army Group Upper Rhine (Heeresgruppe Oberrhein) launched a major offensive against the thinly stretched, 110 kilometres (70 mi) line of the Seventh U.S. Army. This offensive, known as Unternehmen Nordwind (Operation North Wind), was the last major German offensive of the war on the Western Front. The weakened Seventh Army had, at Eisenhower's orders, sent troops, equipment, and supplies north to reinforce the American armies in the Ardennes, and the offensive left it in dire straits.

By 15 January, Seventh Army's VI Corps was fighting on three sides in Alsace. With casualties mounting, and running short on replacements, tanks, ammunition, and supplies, Seventh Army was forced to withdraw to defensive positions on the south bank of the Moder River on 21 January. The German offensive drew to a close on 25 January. In the bitter, desperate fighting of Operation Nordwind, VI Corps, which had borne the brunt of the fighting, suffered a total of 14,716 casualties. The total for Seventh Army for January was 11,609.[4] Total casualties included at least 9,000 wounded.[101] First, Third and Seventh Armies suffered a total of 17,000 hospitalized from the cold.[4][lower-alpha 14]

Allies prevail

.jpg)

While the German offensive had ground to a halt, they still controlled a dangerous salient in the Allied line. Patton's Third Army in the south, centered around Bastogne, would attack north, Montgomery's forces in the north would strike south, and the two forces planned to meet at Houffalize.

The temperature during January 1945 was extremely low. Weapons had to be maintained and truck engines run every half-hour to prevent their oil from congealing. The offensive went forward regardless.

Eisenhower wanted Montgomery to go on the counter offensive on 1 January, with the aim of meeting up with Patton's advancing Third Army and cutting off most of the attacking Germans, trapping them in a pocket. However, Montgomery, refusing to risk underprepared infantry in a snowstorm for a strategically unimportant area, did not launch the attack until 3 January, by which time substantial numbers of German troops had already managed to fall back successfully, but at the cost of losing most of their heavy equipment.

At the start of the offensive, the First and Third U.S. Armies were separated by about 40 km (25 mi). American progress in the south was also restricted to about a kilometer a day. The majority of the German force executed a successful fighting withdrawal and escaped the battle area, although the fuel situation had become so dire that most of the German armor had to be abandoned. On 7 January 1945, Hitler agreed to withdraw all forces from the Ardennes, including the SS-Panzerdivisionen, thus ending all offensive operations. However, considerable fighting went on for another 3 weeks; St. Vith was recaptured by the Americans on 23 January, and the last German units participating in the offensive did not return to their start line until 25 January.

Winston Churchill, addressing the House of Commons following the Battle of the Bulge said, "This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever-famous American victory."[103]

Strategy and leadership

Hitler's chosen few

The plan and timing for the Ardennes attack sprang purely from the mind of Adolf Hitler. He believed a critical fault line existed between the British and American military commands, and that a heavy blow on the Western Front would shatter this alliance. Planning for the "Watch on the Rhine" offensive emphasized secrecy and the commitment of overwhelming force. Due to the use of landline communications within Germany, motorized runners carrying orders, and draconian threats from Hitler, the timing and mass of the attack was not detected by ULTRA codebreakers and achieved complete surprise. The allied leadership never saw it coming.[104]

Hitler had always resented the blue-blood Prussian leadership of the German army. So, when selecting leadership for the attack, he felt that the implementation of this decisive blow should be entrusted to his own Nazi party army, the Waffen-SS. Ever since German regular Army officers attempted to assassinate him, he had increasingly trusted only the SS and its heavily armed branch, the Waffen-SS.[105] After the invasion of Normandy, the SS armored units had suffered significant leadership casualties. These losses included SS-Gruppenführer (Major General) Kurt Meyer, commander of the 12th SS Panzer (Armor) Division, captured by Belgian partisans on September 6, 1944.[106]:10 [107]:308 The tactical efficiency of these units were somewhat reduced. The strong right flank of the assault was therefore composed mostly of SS Divisions under the command of "Sepp" (Joseph) Dietrich, a fanatical political disciple of Hitler, and a loyal follower from the early days of the rise of National Socialism in Germany. The leadership composition of the Sixth Panzer Division had a distinctly political nature.[53]

None of the German field commanders entrusted with planning and executing the offensive believed it was possible to capture Antwerp. Even Sepp Dietrich, commanding the strongest arm of the attack, felt that the Ardennes was a poor area for armored warfare, and that the inexperienced and badly equipped Volksgrenadier units would clog the roads that the tanks would need for their rapid advance. In this Dietrich was proved correct. The horse drawn artillery and rocket units were a significant obstacle to the tanks.[20]:113 Other than making futile objections to Hitler in private, he generally stayed out of the planning for the offensive. Model and Manteuffel, the technical experts from the eastern front, took the view that a limited offensive with the goal of surrounding and crushing the American 1st Army would be the best the offensive could hope for. These revisions shared the same fate as Dietrich's objections. In the end, the headlong drive on Elsenborn Ridge would not benefit from support from German units that had already bypassed the ridge. The decision to stop the attacks on the twin villages and change the axis of the attacks southward to the hamlet of Domäne Bütgenbach, was also made by Dietrich.[108]:224 This decision played into American hands, as Robertson had already decided to abandon the villages. However, the staff planning and organization of the attack was well done; most of the units committed to the offensive reached their jump off points undetected and were well organized and supplied for the attack.

Allied high-command controversy

On the American side, most of the upper levels of leadership above division level took themselves out of the battle due to poor handling of intelligence, and the decision not to provide a mobile reserve force for meeting unforeseen contingencies.[108]:162

One of the fault lines between the British and American high commands was General Dwight D. Eisenhower's commitment to a broad front advance with no strategic reserve. This view was opposed by the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Alan Brooke, who promoted a rapid advance on a narrow front, with the other allied armies in reserve.[108]:91 This basic disagreement was the wedge Hitler hoped to exploit with his counteroffensive, and the fact that a breakthrough was achieved seemed to justify the British objections. Also the British remembered a similar German armored counterattack at Kasserine Pass in North Africa, where the American army was routed by the German strike, once again confirming the British conservative view of strategy.[109]:339

Montgomery's actions

The abrasive British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery was quick to widen this gap with characteristically inflammatory correspondence and public pronouncements, and a major break with the U.S. command seemed in the offing. Major General Freddie de Guingand, a staff member of Montgomery's 21st Army Group, brilliantly rose to the occasion, and personally smoothed over the crisis on December 30.[110]:489–90

As the Ardennes crisis developed, at 10:30 a.m. on 20 December, Eisenhower telephoned Montgomery and ordered him to assume command of the American First (Hodges) and Ninth Army (Simpson)[111] – which, until then, were under Bradley's overall command. This change in command was ordered because the northern armies had not only lost all communications with Bradley, who was based in Luxembourg City,[112] and the US command structure, but with adjacent units. Without radio or telephone communication Montgomery managed to improvise an effective command and control system based on those of the Duke of Wellington's 'gallopers' of the Battle of Waterloo.

Describing the situation as he found it on 20 December, Montgomery wrote;

The First Army was fighting desperately. Having given orders to Dempsey and Crerar, who arrived for a conference at 11 am, I left at noon for the H.Q. of the First Army, where I had instructed Simpson to meet me. I found the northern flank of the bulge was very disorganized. Ninth Army had two corps and three divisions; First Army had three corps and fifteen divisions. Neither Army Commander had seen Bradley or any senior member of his staff since the battle began, and they had no directive on which to work. The first thing to do was to see the battle on the northern flank as one whole, to ensure the vital areas were held securely, and to create reserves for counter-attack. I embarked on these measures: I put British troops under command of the Ninth Army to fight alongside American soldiers, and made that Army take over some of the First Army Front. I positioned British troops as reserves behind the First and Ninth Armies until such time as American reserves could be created. Slowly but surely the situation was held, and then finally restored. Similar action was taken on the southern flank of the bulge by Bradley, with the Third Army.[111]

Due to the news blackout imposed on the 16th, the change of leadership to Montgomery did not become known to the outside world until eventually SHAEF made a public announcement making clear that the change in command was "absolutely nothing to do with failure on the part of the three American generals".[113]:198 This resulted in headlines in British newspapers. The story was also covered in Stars and Stripes and for the first time British contribution to the fighting was mentioned.

Montgomery asked Churchill if he could give a conference to the press to explain the situation. Though some of his staff were concerned at the image it would give, the conference had been cleared by Alan Brooke, the CIGS, who was possibly the only person to whom Monty would listen.

On the same day as Hitler's withdrawal order, 7 January, Montgomery held his press conference at Zonhoven.[114] Montgomery started with giving credit to the "courage and good fighting quality" of the American troops, characterizing a typical American as a "very brave fighting man who has that tenacity in battle which makes a great soldier", and went on to talk about the necessity of Allied teamwork, and praised Eisenhower, stating, "Teamwork wins battles and battle victories win wars. On our team, the captain is General Ike."

Then Montgomery described the course of the battle for a half-hour. Coming to the end of his speech he said he had "employed the whole available power of the British Group of Armies; this power was brought into play very gradually ... Finally it was put into battle with a bang ... you thus have the picture of British troops fighting on both sides of the Americans who have suffered a hard blow." He stated that he (i.e., the German) was "headed off ... seen off ... and ... written off". "The battle has been the most interesting, I think possibly one of the most interesting and tricky battles I have ever handled.".[115][116][117]

Despite his positive remarks about American soldiers, the overall impression given by Montgomery, at least in the ears of the American military leadership, was that he had taken the lion's share of credit for the success of the campaign, and had been responsible for rescuing the besieged Americans.[118]

His comments were interpreted as self-promoting, particularly his claiming that when the situation "began to deteriorate," Eisenhower had placed him in command in the north. Patton and Eisenhower both felt this was a misrepresentation of the relative share of the fighting played by the British and Americans in the Ardennes (for every British soldier there were thirty to forty Americans in the fight), and that it belittled the part played by Bradley, Patton and other American commanders. In the context of Patton's and Montgomery's well-known antipathy, Montgomery's failure to mention the contribution of any American general beside Eisenhower was seen as insulting. Indeed, General Bradley and his American commanders were already starting their counterattack by the time Montgomery was given command of 1st and 9th U.S. Armies.[119] Focusing exclusively on his own generalship, Montgomery continued to say he thought the counteroffensive had gone very well but did not explain the reason for his delayed attack on 3 January. He later attributed this to needing more time for preparation on the northern front. According to Winston Churchill, the attack from the south under Patton was steady but slow and involved heavy losses, and Montgomery was trying to avoid this situation.

Many American officers had already grown to dislike Montgomery, who was seen by them as an overly cautious commander, arrogant, and all too willing to say uncharitable things about the Americans. The British Prime Minister Winston Churchill found it necessary in a speech to Parliament to explicitly state that the Battle of the Bulge was purely an American victory.

Montgomery subsequently recognized his error and later wrote: "Not only was it probably a mistake to have held this conference at all in the sensitive state of feeling at the time, but what I said was skilfully distorted by the enemy. Chester Wilmot[120] explained that his dispatch to the BBC about it was intercepted by the German wireless, re-written to give it an anti-American bias, and then broadcast by Arnhem Radio, which was then in Goebbels' hands. Monitored at Bradley's H.Q., this broadcast was mistaken for a B.B.C. transmission and it was this twisted text that started the uproar."[117]

Montgomery later said, "Distorted or not, I think now that I should never have held that press conference. So great were the feelings against me on the part of the American generals that whatever I said was bound to be wrong. I should therefore have said nothing." Eisenhower commented in his own memoirs: "I doubt if Montgomery ever came to realize how resentful some American commanders were. They believed he had belittled them—and they were not slow to voice reciprocal scorn and contempt."[121]

Bradley and Patton both threatened to resign unless Montgomery's command was changed. Eisenhower, encouraged by his British deputy Arthur Tedder, had decided to sack Montgomery. However, intervention by Montgomery's and Eisenhower's Chiefs of Staff, Maj. Gen. Freddie de Guingand, and Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, moved Eisenhower to reconsider and allowed Montgomery to apologize.

The German commander of the 5th Panzer Army, Hasso von Manteuffel said of Montgomery's leadership:

The operations of the American 1st Army had developed into a series of individual holding actions. Montgomery's contribution to restoring the situation was that he turned a series of isolated actions into a coherent battle fought according to a clear and definite plan. It was his refusal to engage in premature and piecemeal counter-attacks which enabled the Americans to gather their reserves and frustrate the German attempts to extend their breakthrough.[122]

Casualties

Casualty estimates for the battle vary widely. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, American forces suffered 89,500 casualties including 19,000 killed, 47,500 wounded and 23,000 missing.[15] An official report by the United States Department of the Army lists 108,347 casualties, including 19,246 killed, 62,489 wounded, and 26,612 captured or missing.[123]:92 A preliminary Army report restricted to the First and Third U.S. Armies listed 75,000 casualties (8,400 killed, 46,000 wounded and 21,000 missing).[45] The Battle of the Bulge was the bloodiest battle for U.S. forces in World War II. British losses totaled 1,400. The German Armed Forces High Command's official figure for all German losses on the Western Front during the period 16 December 1944 – 25 January 1945 was 81,834 German casualties, and other estimates range between 60,000 and 125,000.[124][27][29] German historian Hermann Jung lists 67,675 casualties from 16 December 1944 to late January 1945 for the three German armies that participated in the offensive.[125]

Result

Although the Germans managed to begin their offensive with complete surprise and enjoyed some initial successes, they were not able to seize the initiative on the Western front. While the German command did not reach its goals, the Ardennes operation inflicted heavy losses and set back the Allied invasion of Germany by several weeks. The High Command of the Allied forces had planned to resume the offensive by early January 1945, after the wet season rains and severe frosts, but those plans had to be postponed until 29 January 1945 in connection with the unexpected changes in the front.

The Allies pressed their advantage following the battle. By the beginning of February 1945, the lines were roughly where they had been in December 1944. In early February, the Allies launched an attack all along the Western front: in the north under Montgomery toward Aachen; in the center, under Courtney Hodges; and in the south, under Patton. Montgomery's behavior during the months of December and January, including the press conference on 7 January where he appeared to downplay the contribution of the American generals, further soured his relationship with his American counterparts through to the end of the war.

The German losses in the battle were especially critical: their last reserves were now gone, the Luftwaffe had been shattered, and remaining forces throughout the West were being pushed back to defend the Siegfried Line.

In response to the early success of the offensive, on 6 January Churchill contacted Stalin to request that the Soviets put pressure on the Germans on the Eastern Front.[126] On 12 January, the Soviets began the massive Vistula–Oder Offensive, originally planned for 20 January.[127]:39

During World War II, most U.S. black soldiers still served only in maintenance or service positions, or in segregated units. Because of troop shortages during the Battle of the Bulge, Eisenhower decided to integrate the service for the first time.[128]:127 This was an important step toward a desegregated United States military. More than 2,000 black soldiers had volunteered to go to the front.[129]:534 A total of 708 black Americans were killed in combat during World War II.[130]